Arts, Health and Well-Being Across the Military Continuum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Spreadsheet

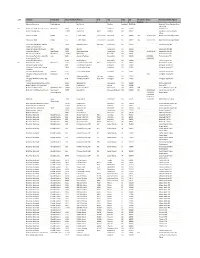

2014 Location Association Street Number Address Unit City State Zip Associated Dates Associated Police Agency Campus Abertay University Study Abroad Bell Street Dundee Scotland DD1 1HG Scotland Police-Dundee Area Command NO Action in Comm Through Service WorkForce 3900 ACTS Lane Dumfries VA 22026 Dumfries PD Action Martial Arts 21690 Redrum Dr. #187 Ashburn VA 20147 Loudoun County Sheriff's Office Affinia 50 Hotel NSMH 155 E 50th Street 513,703,121 New York NY 10022 AN 11/07-11/09 New York Police Department Affinia 50 Hotel NSMH 155 E 50th Street 513,703,121 New York NY 10022 AN 11/14-11/16 New York Police Department Alexandria City Public Schools 1340 Braddock Place 7th Floor Alexandria VA 22314 Alexandria City PD Adult Learning Center Alexandria Detention Center CBO 2003 Mill Rd. Alexandria VA 22314 Alexandria City PD Alexandria Renew WorkForce 1500 Eisenhower Ave Alexandria VA 22314 11/20-12/18 Alexandria City PD American Iron Works WorkForce 13930 Willard Rd. Chantilly VA 20151 Fairfax County PD Americana Park Gerry Connelly Jaye 4130 Accotink Parkway Annandale VA 22003 4/3/2014 Fairfax County PD Cross Country Trail 6-18-2014 Annandale High School 4700 Medord Drive Annandale VA 22003 Fairfax County PD NO Annenberg Learner WorkForce 1301 Pennsylvania Ave NW #302 Washington DC 20004 Washington DC PD Arlington Career Center 816 South Walter Reed Dr. Arlington VA 22204 Arlington County PD Arlington County Fire Training 2800 South Tayler Street Arlington VA 22206 Arlington County PD Academy Arlington Dream Project Pathway 1325 S. Dinwiddie Street Arlington VA 22206 Arlington County PD Arlington Employment Center WorkKeys 2100 2014 Arlington County PD (WIB) Washington Blvd 1st Floor Arlington VA 22204 Arlington Mill Alternative High 816 S. -

Virginia: Birthplace of America

VIRGINIA: BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA Over the past 400 years AMERICAN EVOLUTION™ has been rooted in Virginia. From the first permanent American settlement to its cultural diversity, and its commerce and industry, Virginia has long been recognized as the birthplace of our nation and has been influential in shaping our ideals of democracy, diversity and opportunity. • Virginia is home to numerous national historic sites including Jamestown, Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, Colonial Williamsburg, Arlington National Cemetery, Appomattox Court House, and Fort Monroe. • Some of America’s most prominent patriots, and eight U.S. Presidents, were Virginians – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. • Virginia produced explorers and innovators such as Lewis & Clark, pioneering physician Walter Reed, North Pole discoverer Richard Byrd, and Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, all whose genius and dedication transformed America. • Bristol, Virginia is recognized as the birthplace of country music. • Virginia musicians Maybelle Carter, June Carter Cash, Ella Fitzgerald, Patsy Cline, and the Statler Brothers helped write the American songbook, which today is interpreted by the current generation of Virginian musicians such as Bruce Hornsby, Pharrell Williams, and Missy Elliot. • Virginia is home to authors such as Willa Cather, Anne Spencer, Russell Baker, and Tom Wolfe, who captured distinctly American stories on paper. • Influential women who hail from the Commonwealth include Katie Couric, Sandra Bullock, Wanda Sykes, and Shirley MacLaine. • Athletes from Virginia – each who elevated the standards of their sport – include Pernell Whitaker, Moses Malone, Fran Tarkenton, Sam Snead, Wendell Scott, Arthur Ashe, Gabrielle Douglas, and Francena McCorory. -

National Capital Area

National Capital Area Joint Service Graduation Ceremony For National Capital Consortium Medical Corps, Interns, Residents, and Fellows National Capital Consortium Dental Corps and Pharmacy Residents Health and Business Administration Residents Healthcare Administration Residents Rear Admiral David A. Lane, Medical Corps, U.S. Navy Director National Capital Region Medical Directorate Colonel Michael S. Heimall, Medical Service Corps, U.S. Army Director Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Arthur L. Kellermann, M.D., M.P.H. Professor and Dean, F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Jerri Curtis, M.D. Designated Institutional Official National Capital Consortium Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Colonel Brian M. Belson, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Director for Education Training and Research Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Colonel Clifton E. Yu, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Director, Graduate Medical Education Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Program of Events Academic Procession Arrival of the Official Party Rendering of Honors (Guests, please stand) Presentation of Colors...............................Uniformed Services University Tri-Service Color Guard “National Anthem”...............................................................................The United States Army Band Invocation.................................................................................LTC B. Vaughn Bridges, CHC, USA -

Theodore Roosevelt Formed the Rough Riders (Volunteers) to Fight in the Spanish- American War in Cuba

951. Rough Riders, San Juan Hill 1898 - Theodore Roosevelt formed the Rough Riders (volunteers) to fight in the Spanish- American War in Cuba. They charged up San Juan Hill during the battle of Santiago. It made Roosevelt popular. 952. Treaty of Paris Approved by the Senate on February 6, 1898, it ended the Spanish-American War. The U.S. gained Guam, Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. 953. American Anti-Imperialist League A league containing anti-imperialist groups; it was never strong due to differences on domestic issues. Isolationists. 954. Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, Cuba The U.S. acquired these territories from Spain through the Treaty of Paris (1898), which ended the Spanish-American War. 955. Walter Reed Discovered that the mosquito transmitted yellow fever and developed a cure. Yellow fever was the leading cause of death of American troops in the Spanish-American War. 956. Insular cases Determined that inhabitants of U.S. territories had some, but not all, of the rights of U.S. citizens. 957. Teller Amendment April 1896 - U.S. declared Cuba free from Spain, but the Teller Amendment disclaimed any American intention to annex Cuba. 958. Platt Amendment A rider to the Army Appropriations Bill of 1901, it specified the conditions under which the U.S. could intervene in Cuba's internal affairs, and provided that Cuba could not make a treaty with another nation that might impair its independence. Its provisions where later incorporated into the Cuban Constitution. 959. Protectorate A weak country under the control and protection of a stronger country. Puerto Rico, Cuba, etc. -

Hospitals and Clinics 81

Hospitals and Clinics 81 Chapter Three Hospitals and Clinics INTRODUCT I ON The attack on the Pentagon killed 125 Department of Defense (DoD) personnel outright, including 33 Navy and 22 Army active-duty deaths. Seventy civilians, including nine contractors, also lost their lives. No construction workers were among those killed because they were all working in another area at the time of the crash. Of the many injured survivors who made it out of the building, 125 sought medical care at area hospitals and clinics on 9/11. Approximately 64 were treated and released, and about 61 had physical injuries serious enough to be ad- mitted to medical facilities. Dozens more sought treatment for minor injuries dur- ing the remainder of the week. Military and civilian hospitals treated and admitted both military and civilian casualties. By 15 September, only 20 patients remained in local hospitals. (See the discussion of discrepancies in official casualty counts in Chapter 1.)1(p314),2(pB-15),3–8 Immediately after American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon, area hospitals with previous agreements to work together in a crisis contacted one another. Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) communicated with military and civilian support hospitals in Northern Virginia; Washing- ton, DC; and Maryland. WRAMC’s emergency room staff had been meeting monthly with emergency personnel from hospitals in the DC Hospital Asso- ciation, and communications had been tested every day regarding bed avail- ability and other contingency concerns. In Northern -

Dr. Walter Reed and Yellow Fever Reade W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1926 Dr. Walter Reed and yellow fever Reade W. Corr Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Corr, Reade W., "Dr. Walter Reed and yellow fever" (1926). Honors Theses. Paper 450. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF-FllCHMOND LIBRARIES 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 3 3082 01028 5293 HISTORY ~o// Dr. WALTER REED AND YELLOW FEVER May t926 by Reade w. Corr f A ~. - ur-~o£ ~~~~ 11/l. <f?~ ~ ~ Biblioe;raphy Authorities: *H. A. Kelly: Walter Reed and Yellow Fever. *W. D. Macaw: Walter Reed: A Memoir. Libby: History of Medicine. **Ravenel : A Half Century of Public Health. Cushing: Life of Sir William Osler. *Senate Documents vol. 6t: Yellow Fever. *House Documents vol. 123, no. 757: TyPhoid Fever in the United States Ndlitary camps, Report of the origin and spread of. Encyclopaedias: Life of Walter Reed: Americana. Life of Walter Reed: New International. Magazine and Newspaper Articles: Republic Forgetfulness: Outlook for August 11, 1906. The Inside History of a Great Medical Discovery , by Aristides Agramonte: Scientific Monthly for Dec. 1915. The Walter Reed :Memorial Fund: Science for March 9, 1906. Richmond Times Dispatch for April 11, 1926 *Newport News Daily Press during April 1926. Gloucester' Gazette for April 15, 22 & 29, 1926. tray be obtaiructfrom the Virginia State Library. -

Bearing His Full Name and Practicing Medicine in Chicago

MEMORIAL Xxi rectitude and dignity. Among the children who survive him is a son bearing his full name and practicing medicine in Chicago. GENERAL WILLIAM C. GORGAS. William C. Gorgas was born in Alabama on October 3rd, 1854. He was the son af General Josiah Gorgas, the Chief of Ordnance of the Southern Confederacy and after the Civil War the President of the University of the South. Gorgas was graduated from the Uni- versity of the South with the degree of A.B. in 1875 and from the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1879. He entered the Medical Department of the Army on June 16th, 1880, as first lieutenant, became captain in 1885 and major in 1898. In early life Gorgas had had yellow fever. In those days yellow fever was rightly dreaded. As Gorgas was the only immune among the officers of the Medical Department with the exception of Surgeon-General Stern- berg he was naturally the first one to be thought of for duty that involved exposure to that disease. Having accompanied the expedi- tion against Santiago, he was soon appointed Chief Sanitary Officer of Havana, which office he held from 1898 to 1902. Walter Reed, at that time a major in the Medical Department, was first sent by General Sternberg to Cuba to study yellow fever in 1900 and in June of that year was appointed president of the board of which Carroll, Agramonte and Lazar were the other mem- bers. Gorgas from his position naturally cooperated with the board (Reed acknowledges valuable suggestions from him), but his other duties forbade active participation in the researches which resulted in the memorable discovery of the mode of infection in yellow fever and of the proper means of exterminating that disease. -

Bicycle Element

Master Transportation An element of Arlington County’s Plan Comprehensive Plan Bicycle Element Adopted April 23, 2019 Part 1 Background, Goals and Policies I. The Role of Bicycling in Arlington .....................................................................................................4 II. Background ............................................................................................................................................7 III. Arlington’s Vision for Bicycling ........................................................................................................13 IV. Goals of the MTP and Bicycle Element ..........................................................................................14 V. Policies and Implementation Actions .............................................................................................15 VI. Measures of Performance and Progress Targets ..........................................................................29 Figure 1: Progress Targets with Applicable Goals ........................................................................29 Part 2 Infrastructure Facilities and Implementation VII. Primary Bicycling Corridors and the Bikeway Network .............................................................31 Figure 2: The Primary Bicycling Corridors Map ..........................................................................33 Figure 3: Planned Bikeway Network Map .....................................................................................35 VIII. Network and Program -

Woodrow Wilson's Hidden Stroke of 1919: the Impact of Patient

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 39 (1):E6, 2015 Woodrow Wilson’s hidden stroke of 1919: the impact of patient-physician confidentiality on United States foreign policy Richard P. Menger, MD,1 Christopher M. Storey, MD, PhD,1 Bharat Guthikonda, MD,1 Symeon Missios, MD,1 Anil Nanda, MD, MPH,1 and John M. Cooper, PhD2 1Department of Neurosurgery, Louisiana State University of Health Sciences, Shreveport, Louisiana; and 2University of Wisconsin Department of History, Madison, Wisconsin World War I catapulted the United States from traditional isolationism to international involvement in a major European conflict. Woodrow Wilson envisaged a permanent American imprint on democracy in world affairs through participa- tion in the League of Nations. Amid these defining events, Wilson suffered a major ischemic stroke on October 2, 1919, which left him incapacitated. What was probably his fourth and most devastating stroke was diagnosed and treated by his friend and personal physician, Admiral Cary Grayson. Grayson, who had tremendous personal and professional loyalty to Wilson, kept the severity of the stroke hidden from Congress, the American people, and even the president himself. During a cabinet briefing, Grayson formally refused to sign a document of disability and was reluctant to address the subject of presidential succession. Wilson was essentially incapacitated and hemiplegic, yet he remained an active president and all messages were relayed directly through his wife, Edith. Patient-physician confidentiality superseded national security amid the backdrop of friendship and political power on the eve of a pivotal juncture in the history of American foreign policy. It was in part because of the absence of Woodrow Wilson’s vocal and unwavering support that the United States did not join the League of Nations and distanced itself from the international stage. -

Dr. Walter Reed, M.D., M.A., L.L.D

Dr. Walter Reed, M.D., M.A., L.L.D Dr. Walter Reed (1851-1902) Conqueror of the Yellow Fever Walter Reed was born on September 13, 1851, in a small country home at Belroi, Gloucester County, Virginia. He was the last of five children of the Reverend Lemuel Sutton Reed and his wife Pharaba White. His father was a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church, who moved every two years to a different circuit of the church. It was during a two year service (1851-1852) that Walter was born. He studied medicine at the University of Virginia. On July 1, 1869 Walter and nine other students received their M.D. degrees. He stood third in his class and was the youngest graduate of the Medical Department. Two years after receiving his diploma from Bellevue Hospital Medical College (New York University Medical Center), Reed sought an appointment in the Medical Corps of the United States Army and in 1875 he was commissioned as Assistant Surgeon, with the rank of first lieutenant. In this same year he married Miss Emilie Lawrence, of Murfreesboro, North Carolina. He had two children Walter Lawrence Reed born at Fort Apache (1877) and Emilie Lawrence Reed born at Fort Omaha (1883). Stricken with appendicitis, he died of acute peritonitis on November 23, 1902. On the granite shaft over his grave is a bronze tablet with the legend: "He gave to man control over that dreadful scourge, yellow fever." Even more suitable than bronze as a memorial is the Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, D.C., established by the United States Army in 1906. -

National Naval

At the laying of From the War of 1812 to NNMC the Cornerstone, ince the infancy of our Nation, when drugs often did more harm than good and surgeries took FDR stated, “the place whenever and wherever possible, military medicine in the U.S. has grown to be in the forefront striking architecture of modern medicine and has led the way in innovative emergency quality care in remote and of this great dangerous environments. center (combines) S practical usefulness (with) the harmony In 1812, the appropriated $115,000 for the construction of a 50- of its lines and first naval bed naval hospital at 921 Pennsylvania Avenue, gives expression medical SE, in Washington, D.C., between 9th and 10th to the thought that facility in the Streets. Soon outdated, the Naval Hospital at art is not dead Washington, Pennsylvania Avenue was deemed “antiquated and New Navy Hospital circa 1925 in our midst,” D.C. area was insufficient,” and in 1906, Congress appropriated knew that the very best medical care for our and apparently the US Department of the established $125,000 for a replacement. returning Sailors, Soldiers, Marines and Airmen Interior agreed, designating the original in a rented Tower a historical landmark in 1977, citing Built behind the Old Naval Observatory at 23rd would be needed. December 7, 1941, “a day that building the building’s significance as an outstanding and E Streets NW, the “New Naval Hospital” would live in infamy…” proved him right. near the example of Art Deco architecture. Washington included quarters for sick officers and nurses, a contagious disease building, and administrative President Franklin D. -

Cultural Resources of Harrisonburg

78 THE VIRGINIA TEACHER [Vol. 11, No. 3 VII. The Heritage of Traditions CULTURAL RESOURCES OF Every college builds its own tradi- tions. It does not borrow them. The HARRISONBURG State Teachers College at Hqrrisonburg MIDWAY between Lexington, the has established certain traditions that "Athens of the South," and Win- would be a most valuable heritage for chester, one of the most historic a liberal arts college for women. cities in America; near Charlottes- 1. The Harrisonburg student has a ville, the home of Jefferson, and Staun- hopeful, happy, joyous, optimistic ton, the birthplace of Woodrow Wil- outlook upon life, an attitude that is son; with its main street the scenic Lee the reflection of the influence of the Highway, one of the most celebrated old invigorating and inspiring climate trails in the New World, Harrisonburg en- and scenery of the Valley of Virginia. joys unusual historic, scenic, and cultural 2. There is at Harrisonburg a tradi- resources. tion of unbounded loyalty to the col- The fine associations of the region are lege which places squarely behind suggested to the casual visitor and kept every interest of the institution the alive in the hearts of all residents by the energy and devotion of its 10,000 names of buildings on the campus of the alumnae. State Teachers College. For example, Maury 3. There is at the college the tradition Hall reminds us of the "Pathfinder of the of fine achievement, and dedica- Seas," who spent his last years in active ser- tion of one's energies and talents, vice at Lexington.