Pershing, John Joseph (13 Sept. 1860-15 July 1948), Commander of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking David Fagen: the Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots

Sunland Tribune Volume 31 Article 5 2006 Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots Frank Schubert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Schubert, Frank (2006) "Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 31 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol31/iss1/5 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schubert: Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Re bel's Florida Roots 1 Frank Schubert Miami, Fernandina, and Jacksonville. Among them were all four regiments of black regu avid Fagen was by far the best lars: three (the 9th Cavalry, and the 24th known of the twenty or so black and 25th Infantry regiments) in Tampa, and soldiers who deserted the U.S. a fourth, the 10th Cavalry, in Lakeland. Re DArmy in the Philippines at the cently the experience of these soldiers in turn of the twentieth century and went the Florida has been the subject of a growing next step and defected to the enemy. I !is number of books, articles, and dissertations.2 story fi lled newspapers great and small , Some Floridians joined regular units, from the New Yori? 11imes to the Crawford, and David Fagen was one of those. -

Fort Funston, Panama Mounts for 155Mm Golden Gate National

Fort Funston, Panama Mounts for 155mm Guns HAERNo. CA-193-A B8'•'■ANffiA. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Skyline Boulevard and Great Highway San Francisco San Francisco County California PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior San Francisco, California 38 ) HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD • FORT FUNSTON, PANAMA MOUNTS FOR 155mm GUNS HAERNo.CA-193-A Location: Fort Funston, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, City and County of San Francisco, California Fort Funston is located between Skyline Boulevard and the Pacific Ocean, west of Lake Merced. The Battery Bluff Panama mounts were located at Fort Funston, 1,200 feet north of Battery Davis' gun No. 1, close to the edge of the cliff overlooking the beach Date of Construction: 1937 Engineer: United States Army Corps of Engineers Builder: United States Army Corps of Engineers Present Owner: United States National Park Service Golden Gate National Recreation Area Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Present Use: Not Currently Used Due to erosion, Battery Bluff Panama mounts have slipped to the beach below where they are still visible Significance: The Panama mounts of Battery Bluff are significant as they are a contributing feature to the Fort Funston Historic District which is considered eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The Panama mounts were the only guns of its type to be emplaced in the San Francisco Harbor Defenses. Report Prepared By: Darlene Keyer Carey & Co. Inc., Historic Preservation Architects 123 Townsend Street, Suite 400 San Francisco, CA 94107 Date: February 26, 1998 r FORT FUNSTON, PANAMA MOUNTS FOR 155mm GUNS HAERNO.CA-193-A PAGE 2 HISTORY OF FORT FUNSTON Fort Funston Historic District Fort Funston, which is located in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and is now considered the Fort Funston Historic District. -

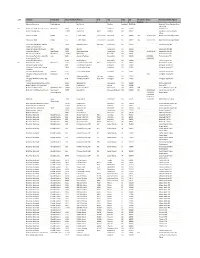

This Spreadsheet

2014 Location Association Street Number Address Unit City State Zip Associated Dates Associated Police Agency Campus Abertay University Study Abroad Bell Street Dundee Scotland DD1 1HG Scotland Police-Dundee Area Command NO Action in Comm Through Service WorkForce 3900 ACTS Lane Dumfries VA 22026 Dumfries PD Action Martial Arts 21690 Redrum Dr. #187 Ashburn VA 20147 Loudoun County Sheriff's Office Affinia 50 Hotel NSMH 155 E 50th Street 513,703,121 New York NY 10022 AN 11/07-11/09 New York Police Department Affinia 50 Hotel NSMH 155 E 50th Street 513,703,121 New York NY 10022 AN 11/14-11/16 New York Police Department Alexandria City Public Schools 1340 Braddock Place 7th Floor Alexandria VA 22314 Alexandria City PD Adult Learning Center Alexandria Detention Center CBO 2003 Mill Rd. Alexandria VA 22314 Alexandria City PD Alexandria Renew WorkForce 1500 Eisenhower Ave Alexandria VA 22314 11/20-12/18 Alexandria City PD American Iron Works WorkForce 13930 Willard Rd. Chantilly VA 20151 Fairfax County PD Americana Park Gerry Connelly Jaye 4130 Accotink Parkway Annandale VA 22003 4/3/2014 Fairfax County PD Cross Country Trail 6-18-2014 Annandale High School 4700 Medord Drive Annandale VA 22003 Fairfax County PD NO Annenberg Learner WorkForce 1301 Pennsylvania Ave NW #302 Washington DC 20004 Washington DC PD Arlington Career Center 816 South Walter Reed Dr. Arlington VA 22204 Arlington County PD Arlington County Fire Training 2800 South Tayler Street Arlington VA 22206 Arlington County PD Academy Arlington Dream Project Pathway 1325 S. Dinwiddie Street Arlington VA 22206 Arlington County PD Arlington Employment Center WorkKeys 2100 2014 Arlington County PD (WIB) Washington Blvd 1st Floor Arlington VA 22204 Arlington Mill Alternative High 816 S. -

Virginia: Birthplace of America

VIRGINIA: BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA Over the past 400 years AMERICAN EVOLUTION™ has been rooted in Virginia. From the first permanent American settlement to its cultural diversity, and its commerce and industry, Virginia has long been recognized as the birthplace of our nation and has been influential in shaping our ideals of democracy, diversity and opportunity. • Virginia is home to numerous national historic sites including Jamestown, Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, Colonial Williamsburg, Arlington National Cemetery, Appomattox Court House, and Fort Monroe. • Some of America’s most prominent patriots, and eight U.S. Presidents, were Virginians – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. • Virginia produced explorers and innovators such as Lewis & Clark, pioneering physician Walter Reed, North Pole discoverer Richard Byrd, and Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, all whose genius and dedication transformed America. • Bristol, Virginia is recognized as the birthplace of country music. • Virginia musicians Maybelle Carter, June Carter Cash, Ella Fitzgerald, Patsy Cline, and the Statler Brothers helped write the American songbook, which today is interpreted by the current generation of Virginian musicians such as Bruce Hornsby, Pharrell Williams, and Missy Elliot. • Virginia is home to authors such as Willa Cather, Anne Spencer, Russell Baker, and Tom Wolfe, who captured distinctly American stories on paper. • Influential women who hail from the Commonwealth include Katie Couric, Sandra Bullock, Wanda Sykes, and Shirley MacLaine. • Athletes from Virginia – each who elevated the standards of their sport – include Pernell Whitaker, Moses Malone, Fran Tarkenton, Sam Snead, Wendell Scott, Arthur Ashe, Gabrielle Douglas, and Francena McCorory. -

National Capital Area

National Capital Area Joint Service Graduation Ceremony For National Capital Consortium Medical Corps, Interns, Residents, and Fellows National Capital Consortium Dental Corps and Pharmacy Residents Health and Business Administration Residents Healthcare Administration Residents Rear Admiral David A. Lane, Medical Corps, U.S. Navy Director National Capital Region Medical Directorate Colonel Michael S. Heimall, Medical Service Corps, U.S. Army Director Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Arthur L. Kellermann, M.D., M.P.H. Professor and Dean, F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Jerri Curtis, M.D. Designated Institutional Official National Capital Consortium Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Colonel Brian M. Belson, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Director for Education Training and Research Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Colonel Clifton E. Yu, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Director, Graduate Medical Education Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Program of Events Academic Procession Arrival of the Official Party Rendering of Honors (Guests, please stand) Presentation of Colors...............................Uniformed Services University Tri-Service Color Guard “National Anthem”...............................................................................The United States Army Band Invocation.................................................................................LTC B. Vaughn Bridges, CHC, USA -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

Theodore Roosevelt Formed the Rough Riders (Volunteers) to Fight in the Spanish- American War in Cuba

951. Rough Riders, San Juan Hill 1898 - Theodore Roosevelt formed the Rough Riders (volunteers) to fight in the Spanish- American War in Cuba. They charged up San Juan Hill during the battle of Santiago. It made Roosevelt popular. 952. Treaty of Paris Approved by the Senate on February 6, 1898, it ended the Spanish-American War. The U.S. gained Guam, Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. 953. American Anti-Imperialist League A league containing anti-imperialist groups; it was never strong due to differences on domestic issues. Isolationists. 954. Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, Cuba The U.S. acquired these territories from Spain through the Treaty of Paris (1898), which ended the Spanish-American War. 955. Walter Reed Discovered that the mosquito transmitted yellow fever and developed a cure. Yellow fever was the leading cause of death of American troops in the Spanish-American War. 956. Insular cases Determined that inhabitants of U.S. territories had some, but not all, of the rights of U.S. citizens. 957. Teller Amendment April 1896 - U.S. declared Cuba free from Spain, but the Teller Amendment disclaimed any American intention to annex Cuba. 958. Platt Amendment A rider to the Army Appropriations Bill of 1901, it specified the conditions under which the U.S. could intervene in Cuba's internal affairs, and provided that Cuba could not make a treaty with another nation that might impair its independence. Its provisions where later incorporated into the Cuban Constitution. 959. Protectorate A weak country under the control and protection of a stronger country. Puerto Rico, Cuba, etc. -

Hospitals and Clinics 81

Hospitals and Clinics 81 Chapter Three Hospitals and Clinics INTRODUCT I ON The attack on the Pentagon killed 125 Department of Defense (DoD) personnel outright, including 33 Navy and 22 Army active-duty deaths. Seventy civilians, including nine contractors, also lost their lives. No construction workers were among those killed because they were all working in another area at the time of the crash. Of the many injured survivors who made it out of the building, 125 sought medical care at area hospitals and clinics on 9/11. Approximately 64 were treated and released, and about 61 had physical injuries serious enough to be ad- mitted to medical facilities. Dozens more sought treatment for minor injuries dur- ing the remainder of the week. Military and civilian hospitals treated and admitted both military and civilian casualties. By 15 September, only 20 patients remained in local hospitals. (See the discussion of discrepancies in official casualty counts in Chapter 1.)1(p314),2(pB-15),3–8 Immediately after American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon, area hospitals with previous agreements to work together in a crisis contacted one another. Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) communicated with military and civilian support hospitals in Northern Virginia; Washing- ton, DC; and Maryland. WRAMC’s emergency room staff had been meeting monthly with emergency personnel from hospitals in the DC Hospital Asso- ciation, and communications had been tested every day regarding bed avail- ability and other contingency concerns. In Northern -

Dr. Walter Reed and Yellow Fever Reade W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1926 Dr. Walter Reed and yellow fever Reade W. Corr Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Corr, Reade W., "Dr. Walter Reed and yellow fever" (1926). Honors Theses. Paper 450. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF-FllCHMOND LIBRARIES 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 3 3082 01028 5293 HISTORY ~o// Dr. WALTER REED AND YELLOW FEVER May t926 by Reade w. Corr f A ~. - ur-~o£ ~~~~ 11/l. <f?~ ~ ~ Biblioe;raphy Authorities: *H. A. Kelly: Walter Reed and Yellow Fever. *W. D. Macaw: Walter Reed: A Memoir. Libby: History of Medicine. **Ravenel : A Half Century of Public Health. Cushing: Life of Sir William Osler. *Senate Documents vol. 6t: Yellow Fever. *House Documents vol. 123, no. 757: TyPhoid Fever in the United States Ndlitary camps, Report of the origin and spread of. Encyclopaedias: Life of Walter Reed: Americana. Life of Walter Reed: New International. Magazine and Newspaper Articles: Republic Forgetfulness: Outlook for August 11, 1906. The Inside History of a Great Medical Discovery , by Aristides Agramonte: Scientific Monthly for Dec. 1915. The Walter Reed :Memorial Fund: Science for March 9, 1906. Richmond Times Dispatch for April 11, 1926 *Newport News Daily Press during April 1926. Gloucester' Gazette for April 15, 22 & 29, 1926. tray be obtaiructfrom the Virginia State Library. -

Funston, Frederick.Pdf

U.S. Army Military History Institute Biographies 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 16 Dec 2011 FREDERICK FUNSTON A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources Army and Navy Journal (24 Feb 1917): p. 818. Per. Obituary tribute. Bain, David H. Sitting in Darkness: Americans in the Philippines. Boston: Hougton Mifflin, 1984. 464 p. DS679.B34. Author's personal odyssey--geographically and historically-- on Funston's 1901 capture of Aquinaldo. Barker, Stockbridge H. "Funston's Folly." Army (Feb 1964): pp. 73-80. Per. Capture of Aguinaldo, 1901. Brown, W.C. "Incidents in Aguinaldo's Capture." Infantry Journal (Jun 1925): p. 627-632. Per. Crouch, Thomas W. “The Making of a Soldier: The Career of Frederick Funston, 1865-1902.” PhD dss, TX, 1969. 637 p. E664.F86.C76. Extensive bibliography, pp. 624-637. _____. A Yankee Guerrillero: Frederick Funston and the Cuban Insurrection, 1896-1897. Memphis, TN: Memphis State, 1975. 165 p. F1786.F86.C76. Cullum, George W. Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy… Boston: Houghton, 1891-1950. U410.H53. Vol. 7, pp. 2077-78; Vol. 8, p. 728; Vol. 9, p. 556. Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. IV. NY: Scribner's, 1931. pp. 73-75. E176.D564. Funston, Frederick. Papers (on microfilm). 3 reels. Borrowed from daughter and microfilmed by KS State Historical Society, 1955. E664.F86.F86Microfilm. Funston, Frederick. Memories of Two Wars: Cuban and Philippine Experiences. Lincoln, NE: U NE, 2009 reprint of 1911 edition. 451 p. DS683.K2.20th.Inf.F85. _____. Report of Brigadier General Frederick Funston, United States Army on the Department of Luzon Field Inspection, 1912. -

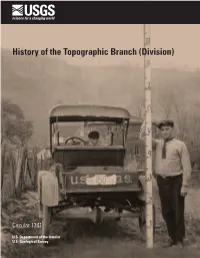

History of the Topographic Branch (Division)

History of the Topographic Branch (Division) Circular 1341 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Rodman holding stadia rod for topographer George S. Druhot near Job, W. Va., 1921. 2 Report Title John F. Steward, a member of the Powell Survey, in Glen Canyon, Colorado River. Shown with field equipment including gun, pick, map case, and canteen. Kane County, Utah, 1872. Photographs We have included these photographs as a separate section to illustrate some of the ideas and provide portraits of some of the people discussed. These photographs were not a part of the original document and are not the complete set that would be required to appropriately rep- resent the manuscript; rather, they are a sample of those available from the time period and history discussed. Figure 1. The Aneroid barometer was used to measure differences in elevation. It was more convenient than the mercurial or Figure 2. The Odometer was used to measure distance traveled by counting the cistern barometer but less reliable. revolutions of a wheel (1871). Figure 3. The Berger theodolite was a precision instrument used Figure 4. Clarence King, the first Director of the U.S. Geological for measuring horizontal and vertical angles. Manufactured by Survey (1879–81). C.L. Berger & Sons, Boston (circa 1901). Figure 6. A U.S. Geological Survey pack train carries men and equipment up a steep slope while mapping the Mount Goddard, California, Quadrangle (circa 1907). Figure 5. John Wesley Powell, the second Director of the U.S. Geological Survey (1881–94). Figure 8. Copper plate engraving of topographic maps provided a permanent record. -

Bearing His Full Name and Practicing Medicine in Chicago

MEMORIAL Xxi rectitude and dignity. Among the children who survive him is a son bearing his full name and practicing medicine in Chicago. GENERAL WILLIAM C. GORGAS. William C. Gorgas was born in Alabama on October 3rd, 1854. He was the son af General Josiah Gorgas, the Chief of Ordnance of the Southern Confederacy and after the Civil War the President of the University of the South. Gorgas was graduated from the Uni- versity of the South with the degree of A.B. in 1875 and from the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1879. He entered the Medical Department of the Army on June 16th, 1880, as first lieutenant, became captain in 1885 and major in 1898. In early life Gorgas had had yellow fever. In those days yellow fever was rightly dreaded. As Gorgas was the only immune among the officers of the Medical Department with the exception of Surgeon-General Stern- berg he was naturally the first one to be thought of for duty that involved exposure to that disease. Having accompanied the expedi- tion against Santiago, he was soon appointed Chief Sanitary Officer of Havana, which office he held from 1898 to 1902. Walter Reed, at that time a major in the Medical Department, was first sent by General Sternberg to Cuba to study yellow fever in 1900 and in June of that year was appointed president of the board of which Carroll, Agramonte and Lazar were the other mem- bers. Gorgas from his position naturally cooperated with the board (Reed acknowledges valuable suggestions from him), but his other duties forbade active participation in the researches which resulted in the memorable discovery of the mode of infection in yellow fever and of the proper means of exterminating that disease.