Living and Labouring As a Music Writer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Birmingham from Microsound to Vaporwave

University of Birmingham From Microsound to Vaporwave Born, Georgina; Haworth, Christopher DOI: 10.1093/ml/gcx095 Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Born, G & Haworth, C 2018, 'From Microsound to Vaporwave: internet-mediated musics, online methods, and genre', Music and Letters, vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 30/03/2017 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Music and Letters following peer review. The version of record Georgina Born, Christopher Haworth; From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre, Music and Letters, Volume 98, Issue 4, 1 November 2017, Pages 601–647 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat. -

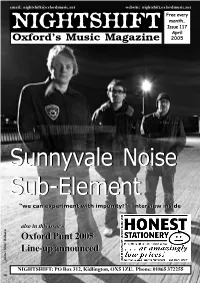

Issue 117.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 117 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SunnyvaleSunnyvale NoiseNoise Sub-ElementSub-Element “we“we cancan experimentexperiment withwith impunity!”impunity!” -- interviewinterview insideinside alsoalso inin thisthis issueissue -- OxfordOxford PuntPunt 20052005 Line-upLine-up announcedannounced photo: Miles Walkden photo: Miles NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE LINE-UP FOR THIS YEAR’S OXFORD PUNT HAS BEEN finalised. The Punt takes place on Wednesay 11th May and features 24 local bands and solo artists playing across eight venues on one night. The Punt is now established as the best showcase of local unsigned music. This year Nightshift received over 100 demos from local acts hoping to take part. The Punt received an added boost last month when Kiss Bar became the eighth venue to be added to the event, meaning we could fit an extra three bands on the bill, making this the biggest Punt ever. The full line up is as follows: Borders: 6.15pm: Laima Bite; 7pm: Kate Chadwick. Jongleurs: 7.30: The Evenings; 8.15: A Silent Film; 9pm: The Factory THE YOUNG KNIVES release a new EP on May 16th on hot new indie Far From The Madding Crowd (in conjunction with Delicious Music): label Transgressive, the label that launched The Subways earlier this 8.15: Zoe Bicat; 9.15: The Thumb Quintet; 10.15: Chantelle Pike. year. Tracks on the limited 10” EP are ‘Coastgard’, ‘Kramer Vs The City Tavern: 8.30: The Half Rabbits; 9.30: Fell City Girl; 10.30: Kramer’, ‘Weekends And Bleak days’ and ‘Trembling Of The Trails’, all Junkie Brush. -

Do You Want Vaporwave, Or Do You Want the Truth?

2017 | Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1 (1) CAPACIOUS Do You Want Vaporwave, or Do You Want the Truth? Cognitive Mapping of Late Capitalist Affect in the Virtual Lifeworld of Vaporwave Alican Koc UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO In "Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism," Frederic Jameson (1991) mentions an “aesthetic of cognitive mapping” as a new form of radical aesthetic practice to deal with the set of historical situations and problems symp- tomatic of late capitalism. For Jameson (1991), cognitive mapping functions as a tool for postmodern subjects to represent the totality of the global late capitalist system, allowing them to situate themselves within the system, and to reenact the critique of capitalism that has been neutralized by postmodernist confusion. Drawing upon a close reading of the music and visual art of the nostalgic in- ternet-based “vaporwave” aesthetic alongside Jameson’s postmodern theory and the afect theory of Raymond Williams (1977) and Brian Massumi (1995; 1998), this essay argues that vaporwave can be understood as an attempt to aestheticize and thereby map out the afective climate circulating in late capitalist consumer culture. More specifcally, this paper argues that through its somewhat obsessive hypersaturation with retro commodities and aesthetics from the 1980s and 1990s, vaporwave simultaneously critiques the salient characteristics of late capitalism such as pastiche, depthlessness, and waning of afect, and enacts a nostalgic long- ing for a modernism that is feeing further and further into an inaccessible history. KEYWORDS Afect, Postmodernism, Late Capitalism, Cognitive Mapping, Aesthetics Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) capaciousjournal.com | DOI: https://doi.org/10.22387/cap2016.4 58 Do You Want Vaporwave, or Do You Want the Truth? Purgatory A widely shared image on the Internet asks viewers to refect on the atrocities of the past century. -

Microgenres MOUG 2021 Presentation (6.531Mb)

Microgenres Memory, Community, and Preserving the Present Leonard Martin Resource Description Librarian Metadata and Digitization Services University of Houston Brief Overview • Microgenres as a cultural phenomenon. • Metadata description for musical microgenres in a library environment using controlled vocabularies and resources. • Challenges and resources for identifying and acquiring microgenre musical sound recordings. • This presentation will focus on chopped and screwed music, vaporwave music, and ambient music. Microgenre noun /mi ∙ cro ∙ gen ∙ re/ 1. A hyper-specific subcategory of artistic, musical, or literary composition characterized that is by a particular style, form, or content. 2. A flexible, provisional, and temporary category used to establish micro- connections among cultural artifacts, drawn from a range of historical periods found in literature, film, music, television, and the performing and fine arts. 3. A specialized or niche genre; either machine-classified or retroactively established through analysis. Examples of Musical Microgenres Hyper-specific • Chopped and screwed music Flexible, provisional, and temporary • Vaporwave music Specialized or niche • Ambient music Ambient Music • Ambient music is a broad microgenre encompassing a breath of natural sounds, acoustic and electronic instruments, and utilizes sampling and/or looping material Discreet Music, Discreet Music, by Brian Eno, 1975, EG Records. to generate repetitive soundscapes. • Earlier works from Erik Satie’s musique d’ameublement (furniture music) to the musique concrete works of Éliane Radigue, Steve Reich’s tape pieces, and synthesizer albums of Wendy Carlos are all precursors of ambient music. • The term ambient music was coined by composer Brian Eno upon the release of Michigan Turquoise, Catch a Blessing. 2019. Genre tags: devotional, ambient, his album, “Discreet Music,” in 1975. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Can Music Make You Sick?: Measuring the Price of Musical

“Musicians often pay a high price for sharing their art with us. Underneath the glow of success can often lie loneliness and exhaustion, not to mention the basic struggles of paying the rent or buying CAN food. Sally Anne Gross and George Musgrave raise important questions – and we need to listen to what the musicians have to tell us about their working conditions and their mental health.” Emma Warren (Music Journalist and Author) MUSIC “Singing is crying for grown-ups. To create great songs or play them with meaning its creators reach far into emotion and fragility seeking the communion we demand of music. The world loves music for bridging those lines. However, music’s toll on musicians can leave deep scars. In this important book, Sally Anne Gross and George Musgrave investigate the relationship between the wellbeing music brings to society and the wellbeing of those who create. It’s a much SICK? YOU MAKE needed reality check, deglamourising the romantic image of the tortured artist.” Crispin Hunt (Multi-Platinum Songwriter/Record Producer, Chair of the Ivors Academy) It is often assumed that creative people are prone to psychological instability, and that this explains apparent associations between cultural production and mental health problems. In their detailed study of recording and performing artists in the British music industry, Sally Anne Gross and George Musgrave turn this view on its head. By listening to how musicians understand and experience their working lives, this book proposes that whilst making music is therapeutic, making a career from music can be traumatic. The authors show how careers based on an all-consuming passion have become more insecure and devalued. -

Xiami Music Genre 文档

xiami music genre douban 2021 年 02 月 14 日 Contents: 1 目录 3 2 23 3 流行 Pop 25 3.1 1. 国语流行 Mandarin Pop ........................................ 26 3.2 2. 粤语流行 Cantopop .......................................... 26 3.3 3. 欧美流行 Western Pop ........................................ 26 3.4 4. 电音流行 Electropop ......................................... 27 3.5 5. 日本流行 J-Pop ............................................ 27 3.6 6. 韩国流行 K-Pop ............................................ 27 3.7 7. 梦幻流行 Dream Pop ......................................... 28 3.8 8. 流行舞曲 Dance-Pop ......................................... 29 3.9 9. 成人时代 Adult Contemporary .................................... 29 3.10 10. 网络流行 Cyber Hit ......................................... 30 3.11 11. 独立流行 Indie Pop ......................................... 30 3.12 12. 女子团体 Girl Group ......................................... 31 3.13 13. 男孩团体 Boy Band ......................................... 32 3.14 14. 青少年流行 Teen Pop ........................................ 32 3.15 15. 迷幻流行 Psychedelic Pop ...................................... 33 3.16 16. 氛围流行 Ambient Pop ....................................... 33 3.17 17. 阳光流行 Sunshine Pop ....................................... 34 3.18 18. 韩国抒情歌曲 Korean Ballad .................................... 34 3.19 19. 台湾民歌运动 Taiwan Folk Scene .................................. 34 3.20 20. 无伴奏合唱 A cappella ....................................... 36 3.21 21. 噪音流行 Noise Pop ......................................... 37 3.22 22. 都市流行 City Pop ......................................... -

Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music Thomas Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2884 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ANALYZING GENRE IN POST-MILLENNIAL POPULAR MUSIC by THOMAS JOHNSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 THOMAS JOHNSON All rights reserved ii Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music by Thomas Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________ ____________________________________ Date Eliot Bates Chair of Examining Committee ___________________ ____________________________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Mark Spicer, advisor Chadwick Jenkins, first reader Eliot Bates Eric Drott THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music by Thomas Johnson Advisor: Mark Spicer This dissertation approaches the broad concept of musical classification by asking a simple if ill-defined question: “what is genre in post-millennial popular music?” Alternatively covert or conspicuous, the issue of genre infects music, writings, and discussions of many stripes, and has become especially relevant with the rise of ubiquitous access to a huge range of musics since the fin du millénaire. -

“Vaporwave Is (Not) a Critique of Capitalism”: Genre Work in an Online Music Scene

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 451-462 Research Article Andrew Whelan, Raphaël Nowak* “Vaporwave Is (Not) a Critique of Capitalism”: Genre Work in An Online Music Scene https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0041 Received June 1, 2018; accepted October 26, 2018 Abstract: Vaporwave, first emerging in the early 2010s, is a genre of music characterised by extensive sampling of earlier “elevator music,” such as smooth jazz, MoR, easy listening, and muzak. Audio and visual markers of the 1980s and 1990s, white-collar workspaces, media technology, and advertising are prominent features of the aesthetic. The (academic, vernacular, and press) writing about vaporwave commonly positions the genre as an ironic or ambivalent critique of contemporary capitalism, exploring the implications of vaporwave for understandings of temporality, memory and technology. The interpretive and discursive labour of producing, discussing and contesting this positioning, described here as “genre work,” serves to constitute and sediment the intelligibility and coherence of the genre. This paper explores how the narrative of vaporwave as an aesthetic critique of late capitalism has been developed, articulated, and disputed through this genre work. We attend specifically to the limits around how this narrative functions as a pedagogical or sensitising device, instructing readers and listeners in how to understand and discuss musical affect, the nature and function of descriptions of music, and perhaps most importantly, the nature of critique, and of capitalism as something meriting such critique. Keywords: vaporwave, internet genre, genre work, critique, online music scene, narrative Introduction Vaporwave is a genre of electronic music that emerged online in the early 2010s, with an aesthetic originally oriented to slowing down and looping ostensibly “kitsch” or “schmaltzy” music from the 1980s and 1990s. -

“Where the Mix Is Perfect”: Voices

“WHERE THE MIX IS PERFECT”: VOICES FROM THE POST-MOTOWN SOUNDSCAPE by Carleton S. Gholz B.A., Macalester College, 1999 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Carleton S. Gholz It was defended on April 11, 2011 and approved by Professor Brent Malin, Department of Communication Professor Andrew Weintraub, Department of Music Professor William Fusfield, Department of Communication Professor Shanara Reid-Brinkley, Department of Communication Dissertation Advisor: Professor Ronald J. Zboray, Department of Communication ii Copyright © by Carleton S. Gholz 2011 iii “WHERE THE MIX IS PERFECT”: VOICES FROM THE POST-MOTOWN SOUNDSCAPE Carleton S. Gholz, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 In recent years, the city of Detroit’s economic struggles, including its cultural expressions, have become focal points for discussing the health of the American dream. However, this discussion has rarely strayed from the use of hackneyed factory metaphors, worn-out success-and-failure stories, and an ever-narrowing cast of characters. The result is that the common sense understanding of Detroit’s musical and cultural legacy tends to end in 1972 with the departure of Motown Records from the city to Los Angeles, if not even earlier in the aftermath of the riot / uprising of 1967. In “‘Where The Mix Is Perfect’: Voices From The Post-Motown Soundscape,” I provide an oral history of Detroit’s post-Motown aural history and in the process make available a new urban imaginary for judging the city’s wellbeing. -

Go Viral 9-5.Pdf

Hello fellow musicians, artists, rappers, bands, and creatives! I’m excited you’ve decided to invest into your music career and get this incredible list of music industry contacts. You’re being proactive in chasing your own goals and dreams and I think that’s pretty darn awecome! Getting your awesome music into the media can have a TREMENDOUS effect on building your fan base and getting your music heard!! And that’s exactly what you can do with the contacts in this book! I want to encourage you to read the articles in this resource to help guide you with how and what to submit since this is a crucial part to getting published on these blogs, magazines, radio stations and more. I want to wish all of you good luck and I hope that you’re able to create some great connections through this book! Best wishes! Your Musical Friend, Kristine Mirelle VIDEO TUTORIALS Hey guys! Kristine here J I’ve put together a few tutorials below to help you navigate through this gigantic list of media contacts! I know it can be a little overwhelming with so many options and places to start so I’ve put together a few videos I’d highly recommend for you to watch J (Most of these are private videos so they are not even available to the public. Just to you as a BONUS for getting “Go Viral” TABLE OF CONTENTS What Do I Send These Contacts? There isn’t a “One Size Fits All” kind of package to send everyone since you’ll have a different end goal with each person you are contacting.