Lydia I. Heeley Mphil Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calum Colvin's Ossian Project and the Tropes of Scottish Photography

Murdo Macdonald: Art and the Scottish Highlands: An Ossianic Perspective 89 MEMORY , MYTH AND MELANCHOLY : CALUM COLV I N ’S OSS I AN PROJECT AND THE TROPES OF SCOTT I SH PHOTO G RAPHY Tom Normand There is a remarkable coincidence of purpose between James Macpherson’s Ossian ‘translations’ of 1760 and Calum Colvin’s Ossian project of 2002 1. Although the former was an exercise in poetic transcription, and the latter an essay in photographic invention, both were journeys of discovery and fabrication. The precise degree of Macpherson’s construction of the Ossian myth remains, even today, a moot point, but Colvin has drawn on this ambiguity to create a collection of evocative and fragmented images. These are a contemporary parallel to Macpherson’s fiction; consciously recalling the process of discovery, imitation, adaptation and simulation that has suffused the ‘original’ source. Significantly, this method is entirely compatible with Colvin’s creative manner. Colvin is a photographer who ‘constructs’ and manipulates his images. He will fabricate a three-dimensional set, using a mixture of abandoned furniture, found-objects, toys and other kitsch memorabilia. Having set the scene he will over-paint the theatrical tableaux with a figurative illustration, often ‘borrowed’ or ‘sampled’from a traditional work of art. And, finally, he will photograph this astonishing creation, so generating a visionary ‘picture’. In reflecting on this process it is clear that the object that exists in the actual world is a fictionalised painted environment, but the result is a ‘real’ photographic study. This challenging dialogue between truth and fiction was certainly relevant to Macpherson, and it manifestly exists as a core dynamic in Colvin’s creative practice. -

'The Neo-Avant-Garde in Modern Scottish Art, And

‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ CRAIG RICHARDSON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (BY PUBLISHED WORK) THE SCHOOL OF FINE ART, THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART 2017 1 ‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ Abstract. The submitted publications are concerned with the historicisation of late-modern Scottish visual art. The underpinning research draws upon archives and site visits, the development of Scottish art chronologies in extant publications and exhibitions, and builds on research which bridges academic and professional fields, including Oliver 1979, Hartley 1989, Patrizio 1999, and Lowndes 2003. However, the methodology recognises the limits of available knowledge of this period in this national field. Some of the submitted publications are centred on major works and exhibitions excised from earlier work in Gage 1977, and Macmillan 1994. This new research is discussed in a new iteration, Scottish art since 1960, and in eight other publications. The primary objective is the critical recovery of little-known artworks which were formed in Scotland or by Scottish artists and which formed a significant period in Scottish art’s development, with legacies and implications for contemporary Scottish art and artists. This further serves as an analysis of critical practices and discourses in late-modern Scottish art and culture. The central contention is that a Scottish neo-avant-garde, particularly from the 1970s, is missing from the literature of post-war Scottish art. This was due to a lack of advocacy, which continues, and a dispersal of knowledge. Therefore, while the publications share with extant publications a consideration of important themes such as landscape, it reprioritises these through a problematisation of the art object. -

Kildonan House

KILDONAN HOUSE 4 & 4B LINKS CRESCENT, ST ANDREWS, FIFE Principal parts of ground-floor of Kildonan House semi-detached Victorian villa Close to world-famous Old Course 4 & 4B LINKS CRESCENT, ST ANDREWS, FIFE, KY16 9HP Well placed for university, shops, pubs & restaurants Pair of ground-floor apartments Potential to reconvert into a single substantial dwelling One with private, south-facing garden Private south-facing garden & shared lawn – 4B Links Crescent – Sun room, sitting room, kitchen, bedroom & shower/wet room Private, south-facing garden. Shed. Shared lawn EPC = C – 4 Links Crescent – Sitting room, kitchen, bedroom & shower room Small yard/garden beds. Shared lawn EPC = D Savills Edinburgh Wemyss House 8 Wemyss Place Edinburgh EH3 6DH 0131 247 3738 [email protected] savills.co.uk 4 Links Crescent SITUATION harbours and sandy unspoilt 4 and 4B Links beaches. Leuchars railway station Crescent are situated in (4 miles) is on the main Aberdeen the row of substantial to London line and connects to Victorian villas to the Dundee and Edinburgh. Edinburgh south side of the main Airport, with its range of domestic and road into St Andrews international flights, is only 50 miles away. which runs parallel to The Links and the famous DESCRIPTION Old Course. The Kildonan was a substantial semi-detached Victorian entrance to the Royal & sandstone villa built in 1898 for Provost Murray of Ancient Golf Club offices is 4B Links Crescent St. Andrews, an acquaintance of Old Tom Morris. diagonally opposite and Golf Place, the Kildonan was subdivided in the late 1940s into three flats – street which leads to the 18th Green of the Old Course, the Royal regular host to the Open Championship which will next be staged Nos 4, 6 & 8. -

Flat 4 10 Links Crescent, St Andrews, Fife

FLAT 4 10 LINKS CRESCENT, ST ANDREWS, FIFE FLAT 4 10 LINKS CRESCENT, ST ANDREWS, FIFE KY16 9HP REFURBISHED FLAT IN PRIME ST ANDREWS SETTING Fully upgraded flat in annexe of Victorian villa Ground and first floor. Own front door New kitchen & shower rooms. Solid oak flooring Close to world famous Old Course Well placed for university, shops, pubs and restaurants Hall, Living Room and Kitchen Principal Bedroom with En Suite Shower Room Bedroom 2, Shower Room Shared Grounds, Own Green EPC = D savills.co.uk DIRECTIONS DESCRIPTION Driving into St Andrews on the A91, 10 Links Crescent, is on the right hand side directly opposite The Flat 4, 10 Links Crescent is a ground and first floor flat in a stone built annexe behind a Victorian villa. Rusacks Hotel. The property has been fully refurbished and redecorated with solid oak flooring throughout the ground floor. A new kitchen and shower rooms have been installed. Go down the drive to the side of the house to reach the front door to Flat 4. The front door gives access to a hall with the living room off. It has a fireplace with a multi fuel stove and recessed shelves with a cupboard below. SITUATION 10 Links Crescent is situated in the row of substantial Victorian villas to the south side of the main road Opposite the living room is the new fitted kitchen with Baumatic microwave and oven, Bosch gas hob into St Andrews which runs parallel to The Links and the famous Old Course. The entrance to the with extractor fan above, Belfast sink, integrated fridge, dishwasher and washing machine. -

Scottish Art: Then and Now

Scottish Art: Then and Now by Clarisse Godard-Desmarest “Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now”, an exhibition presented in Edinburgh by the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture tells the story of collecting Scottish art. Mixing historic and contemporary works, it reveals the role played by the Academy in championing the cause of visual arts in Scotland. Reviewed: Tom Normand, ed., Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now Collected by the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, Edinburgh, The Royal Scottish Academy, 2017, 248 p. The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) have collaborated to present a survey of collecting by the academy since its formation in 1826 as the Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now (4 November 2017-7 January 2018) is curated by RSA President Arthur Watson, RSA Collections Curator Sandy Wood and Honorary Academician Tom Normand. It has spawned a catalogue as well as a volume of fourteen essays, both bearing the same title as the exhibition. The essay collection, edited by Tom Normand, includes chapters on the history of the RSA collections, the buildings on the Mound, artistic discourse in the nineteenth century, teaching at the academy, and Normand’s “James Guthrie and the Invention of the Modern Academy” (pp. 117–34), on the early, complex history of the RSA. Contributors include Duncan Macmillan, John Lowrey, William Brotherston, John Morrison, Helen Smailes, James Holloway, Joanna Soden, Alexander Moffat, Iain Gale, Sandy Wood, and Arthur Watson. -

The Magazine of the Glasgow School of Art Issue 1

Issue 1 The Magazine of The Glasgow School of Art FlOW ISSUE 1 Cover Image: The library corridor, Mackintosh Building, photo: Sharon McPake >BRIEFING Funding increase We√come Research at the GSA has received a welcome cash boost thanks to a rise in Welcome to the first issue of Flow, the magazine of The Glasgow School of Art. funding from the Scottish Higher Education Funding In this issue, Ruth Wishart talks to Professor Seona Reid about the changes and Council (SHEFC).The research challenges ahead for Scotland’s leading art school. This theme is continued by grant has risen from £365,000 to £1.3million, as a result Simon Paterson, GSA Chairman, in his interview Looking to the Future which of the Research Assessment outlines the exciting plans the School has to transform its campus into a Exercise carried out in 2001. world-class learning environment. President’s dinner A dinner to encourage Creating a world-class environment for teaching and research is essential if potential ambassadors for the GSA was held in the the GSA is to continue to contribute to Scotland, the UK and beyond. Every Mackintosh Library by Lord year 300 students graduate from the GSA and Heather Walton talks to some Macfarlane of Bearsden, the School’s Honorary President. of them about the role the GSA plays in the cultural, social and economic life In his after dinner speech, Lord of the nation. One such graduate is the artist Ken Currie, recently appointed Wilson of Tillyorn, the recently appointed Chairman of the Visiting Professor within the School of Fine Art, interviewed here by Susannah National Museums of Scotland, Thompson. -

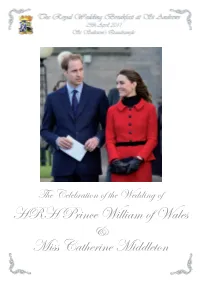

Breakfast Programme

The Celebration of the Wedding of HRH Prince William of Wales & Miss Catherine Middleton Site Map 2 About the Event Today, two of St Andrews’ most famous recent graduates are due to be married in Westminster Abbey in London with the eyes of the world upon them. As the town in which they met and their relationship blossomed, we are delighted to be able to welcome you to our celebrations in honour of the Royal Couple, HRH Prince William of Wales and Miss Catherine Middleton. A variety of entertainment and activities await, building up towards the big moment at around 10:45am where the Royal Couple will be making their entrance into the Abbey for the ceremony itself (due to start at 11am). This will be shown live on the large outdoor screen situated in the main Quadrangle. The “Wedding Breakfast” will be served from 8am on the lower lawn from the marquee with a selection of hot and cold food/drink available. Food will also be on sale throughout the day from local vendors. After the ceremony, and the traditional ‘appearance at the balcony’ the entertainment on the main stage will pick up again, taking the party on to 4pm. The main purpose of the day, aside from having fun, is to raise money for the Royal Wedding Charitable Fund. The list of charities we will be collecting for appears later in the programme. Most of what you see today is provided for free, but we would encourage you to please give generously. The organising committee hope you enjoy this momentous occasion and we are sure you will join with us in extending our warmest wishes and heartfelt congratulations to “Wills & Kate” as they look forward to a long and happy life together. -

Century British Photography and the Case of Walter Benington by Robert William Crow

Reputations made and lost: the writing of histories of early twentieth- century British photography and the case of Walter Benington by Robert William Crow A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Technology January 2015 Abstract Walter Benington (1872-1936) was a major British photographer, a member of the Linked Ring and a colleague of international figures such as F H Evans, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Alvin Langdon Coburn. He was also a noted portrait photographer whose sitters included Albert Einstein, Dame Ellen Terry, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and many others. He is, however, rarely noted in current histories of photography. Beaumont Newhall’s 1937 exhibition Photography 1839-1937 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is regarded by many respected critics as one of the foundation-stones of the writing of the history of photography. To establish photography as modern art, Newhall believed it was necessary to create a direct link between the master-works of the earliest photographers and the photographic work of his modernist contemporaries in the USA. He argued that any work which demonstrated intervention by the photographer such as the use of soft-focus lenses was a deviation from the direct path of photographic progress and must therefore be eliminated from the history of photography. A consequence of this was that he rejected much British photography as being “unphotographic” and dangerously irrelevant. Newhall’s writings inspired many other historians and have helped to perpetuate the neglect of an important period of British photography. -

Professor Dr. Horst W. Drescher, Lothar Görke, Professor Dr

2 Scottish Studies Newsletter, No. 40, Autumn 2012 Editors: Professor Dr. Horst W. Drescher, Lothar Görke, Professor Dr. Klaus Peter Müller, Ronald Walker Table of contents Editorial 3 New Scottish Poetry 4 Miriam Schröder, 65 Years of Passion for Literature – 5 The Scottish Universities' International Summer School Hanne Wiesner, My Edinburgh Experience: 6 English Courses at the University of Edinburgh Dominik J. Strauß, The Boy Who Trapped the Sun: 8 Talented Singer / Songwriter from the Outer Hebrides David S. Forsyth, Transforming a Victorian Vision: 9 Recreating the National Museum of Scotland for the Twenty-First Century (part 2) (New) Media on Scotland 11 Education Scotland 20 Scottish Award Winners 23 The Editors, Miriam Schröder, Ilka Schwittlinsky & Hanne Wiesner, 25 New Publications May – October 2012 Book Reviews Amy Blakeway on The Scottish Middle March, 1573 - 1625; 37 Steve Gardham on The Ballad Repertoire of Anna Gordon; 40 Klaus Peter Müller on Social Justice and Social Policy in Scotland 43 Conference Report (Ron Walker on 'Crime Scotland', Göttingen 2012) 54 Conference Announcements 57 Scottish Studies Newsletter 40, November 2012 3 Editorial Dear Subscriber / Reader, The SNP has now got another two years left to convince the Scots that independence would be better for them than what they have at the moment. This will not be easy. Human beings generally prefer to stay where they are and what they are, especially when they are not sure that a radical change will really bring improvements. And not only Ian Rankin thinks that Scots basically abhor change. Sociologists, economists, many people working in the social services, investigating social policy, and the social, economic, and political situation in Scot- land, however, claim that there is an urgent need for radical changes. -

A Tour Through Scotland

M2 . f • • &¥ be &J L~a- nA-cr_ g hgRiw'd &E&m*= it? $- .8 1#-5 -- ./ ~7~ • M33 ;)() LO A Tour Through Scotland: A Finding Aid of Scottish Travel Photography at the Archival & Special Collections, University of Guelph C \ By Danielle McAllister Honours Bachelors of Arts, Studio Art, University of Guelph, 2007" A Thesis Project Presented to Ryerson University. the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film In partial fulfillment for the degree of Masters of Arts . In the program of . Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Toronto, Ontario, Canada 2010 © Danielle McAllister PRDPERTYOF RYERSON UNIVERSITY UBRARl ±brSS Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. I authorize Ryerson University and George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, to lend this thesis project to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ,. - I --I I Danielle McAllister , I further authorize Ryerson University and George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film to reproduce this thesis project by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or ~ individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ii §k 1 I Abstract I i Among the various collections housed in the Archival & Special Collections CASC) at the University of Guelph is a group of photographic material that exhibits the integral role photography played in Scotland's tourism industry from the I nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Photographic publishing firms such as I G.W. Wilson & Co. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Paper and Light: the Calotype in France and Great Britain, 1839-1870

Paper and Light r-.~heCalotype in Franceand GreatBritain, 183 9-18 7 0 The Museum of FineArts, Houston September24-November 21, 1982 Organized by the Museum of fine Arts , Houston, and the Art Institute of Chicago in cooperation with the Univer sity of Texas at Austin. The exhibition and its catalogue were made possible in part through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D .C., a federal agency . The exhibition will be shown at the Art Institute of Chicago from December 15, 1982, to February 13, 1983. Designed by Michael Glass Design, Inc ., Chicago, Illinois The information in this brochure was drawn from Paper and Light: The Calotype in France and Great Britain , 18 39-1870 (at press). All rights reserved . No portion of this brochure may be used without permission of the Pub lications Department , the Art Institute of Chicago. A 1'6'~ [982- '1 I L-. 7- A Symposium on 17thCentury FrenchPainting Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with Saint John on Patmos, c . 1640, oil on canvas,T he Art Institute of The Art Institute of Chicago Chicago, A. A. Munger. H :E ;>;"' :E ::r P> !:!..::ro Friday, October 29, 1982 Friday, October 29 <n O Pl S 0 "' ~ .... ' < Pl and Saturday, October 30, 1982 (JQ. s ;ii :::, 6:00 Inspiration of the Poet: Reflections on Two Paintings by Nicolas 5· fE S ~ Poussin, Marc Fumaroli, Professor, The Sorbonne, Pari s. Pl :::, (1) Pl s· p.:, ~ - -<= OQ :::i < A symposium of American and European scholars to be held n ,O"'~ Saturday, October 30 8. r::r''-< ::;' in conjunction with the exhibition France in the Golden Age: 10:00 Opening Remarks (t):::, (1)p.:, I") ~ (J'J-· 17th Century French Painting in Ameri can Collections at the Art 0-::rp_.