'The Neo-Avant-Garde in Modern Scottish Art, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter Scott and the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 5 2007 "A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott nda the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement Margery Palmer McCulloch University of Glasgow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McCulloch, Margery Palmer (2007) ""A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott nda the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 44–56. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Margery Palmer McCulloch "A very curious emptiness": Walter Scott and the Twentieth-Century Scottish Renaissance Movement Edwin Muir's characterization in Scott and Scotland (1936) of "a very cu rious emptiness .... behind the wealth of his [Scott's] imagination'" and his re lated discussion of what he perceived as the post-Reformation and post-Union split between thought and feeling in Scottish writing have become fixed points in Scottish criticism despite attempts to dislodge them by those convinced of Muir's wrong-headedness.2 In this essay I want to take up more generally the question of twentieth-century interwar views of Walter Scott through a repre sentative selection of writers of the period, including Muir, and to suggest pos sible reasons for what was often a negative and almost always a perplexed re sponse to one of the giants of past Scottish literature. -

Calum Colvin's Ossian Project and the Tropes of Scottish Photography

Murdo Macdonald: Art and the Scottish Highlands: An Ossianic Perspective 89 MEMORY , MYTH AND MELANCHOLY : CALUM COLV I N ’S OSS I AN PROJECT AND THE TROPES OF SCOTT I SH PHOTO G RAPHY Tom Normand There is a remarkable coincidence of purpose between James Macpherson’s Ossian ‘translations’ of 1760 and Calum Colvin’s Ossian project of 2002 1. Although the former was an exercise in poetic transcription, and the latter an essay in photographic invention, both were journeys of discovery and fabrication. The precise degree of Macpherson’s construction of the Ossian myth remains, even today, a moot point, but Colvin has drawn on this ambiguity to create a collection of evocative and fragmented images. These are a contemporary parallel to Macpherson’s fiction; consciously recalling the process of discovery, imitation, adaptation and simulation that has suffused the ‘original’ source. Significantly, this method is entirely compatible with Colvin’s creative manner. Colvin is a photographer who ‘constructs’ and manipulates his images. He will fabricate a three-dimensional set, using a mixture of abandoned furniture, found-objects, toys and other kitsch memorabilia. Having set the scene he will over-paint the theatrical tableaux with a figurative illustration, often ‘borrowed’ or ‘sampled’from a traditional work of art. And, finally, he will photograph this astonishing creation, so generating a visionary ‘picture’. In reflecting on this process it is clear that the object that exists in the actual world is a fictionalised painted environment, but the result is a ‘real’ photographic study. This challenging dialogue between truth and fiction was certainly relevant to Macpherson, and it manifestly exists as a core dynamic in Colvin’s creative practice. -

KARLA BLACK Born 1972 in Alexandria, Scotland Lives And

KARLA BLACK Born 1972 in Alexandria, Scotland Lives and works in Glasgow Education 2002-2004 Master of Fine Art, Glasgow School of Art 1999-2000 Master of Philosophy (Art in Organisational Contexts), Glasgow School of Art 1995-1999 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Sculpture, Glasgow School of Art Solo Exhibitions 2021 Karla Black: Sculptures 2000 - 2020, FruitMarket Gallery, Edinburgh 2020 Karla Black: 20 Years, Des Moines Art Centre, Des Moines 2019 Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2018 The Power Plant, Toronto Karla Black / Luke Fowler, Capitain Petzel, Berlin 2017 Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London Festival d’AutoMne, Musée des Archives Nationales and École des Beaux-Arts, Paris MuseuM Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle 2016 Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan A New Order (with Kishio Suga), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh David Zwirner, New York Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2015 Irish MuseuM of Modern Art, Dublin 2014 Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan David Zwirner, New York 2013 Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover Institute of ConteMporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne GeMeenteMuseuM, The Hague 2012 Concentrations 55, Dallas MuseuM of Art, Dallas Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London 2011 Scotland + Venice 2011 (curated by The FruitMarket Gallery), Palazzo Pisani, 54th Venice Biennale, Venice 2010 Capitain Petzel, Berlin WittMann Collection, Ingolstadt -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

Argyll & the Isles

EXPLORE 2020-2021 ARGYLL & THE ISLES Earra-Ghàidheal agus na h-Eileanan visitscotland.com Contents The George Hotel 2 Argyll & The Isles at a glance 4 Scotland’s birthplace 6 Wild forests and exotic gardens 8 Island hopping 10 Outdoor playground 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 38 Leisure activities 40 Shopping Welcome to… 42 Food & drink 46 Tours ARGYLL 49 Transport “Classic French Cuisine combined with & THE ISLES 49 Events & festivals Fáilte gu Earra-Gháidheal ’s 50 Accommodation traditional Scottish style” na h-Eileanan 60 Regional map Extensive wine and whisky selection, Are you ready to fall head over heels in love? In Argyll & The Isles, you’ll find gorgeous scenery, irresistible cocktails and ales, quirky bedrooms and history and tranquil islands. This beautiful region is Scotland’s birthplace and you’ll see castles where live music every weekend ancient kings were crowned and monuments that are among the oldest in the UK. You should also be ready to be amazed by our incredibly Cover: Crinan Canal varied natural wonders, from beavers Above image: Loch Fyne and otters to minke whales and sea eagles. Credits: © VisitScotland. Town Hotel of the Year 2018 Once you’ve started exploring our Kenny Lam, Stuart Brunton, fascinating coast and hopping around our dozens of islands you might never Wild About Argyll / Kieran Duncan, want to stop. It’s time to be smitten! Paul Tomkins, John Duncan, Pub of the Year 2019 Richard Whitson, Shane Wasik/ Basking Shark Scotland, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh / Bar Dining Hotel of the Year 2019 Peter Clarke 20ARS Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM). -

Graeme Todd the View from Now Here

GRAEME TODD The View from Now Here 1 GRAEME TODD The View from Now Here EAGLE GALLERY EMH ARTS ‘But what enhanced for Kublai every event or piece of news reported by his inarticulate informer was the space that remained around it, a void not filled by words. The descriptions of cities Marco Polo visited had this virtue: you could wander through them in thought, become lost, stop and enjoy the cool air, or run off.’ 1 I enjoy paintings that you can wander through in thought. At home I have a small panel by Graeme Todd that resembles a Chinese lacquer box. In the distance of the image is the faint tracery of a fallen city, caught within a surface of deep, fiery red. The drawing shows only as an undercurrent, overlaid by thinned- down acrylic and layers of varnish that have been polished to a silky patina. Criss-crossing the topmost surface are a few horizontal streaks: white tinged with purple, and bright, lime green. I imagine they have been applied by pouring the paint from one side to the other – the flow controlled by the way that the panel is tipped – this way and that. I think of the artist in his studio, holding the painting in his hands, taking this act of risk. Graeme Todd’s images have the virtue that, while at one glance they appear concrete, at another, they are perpetually fluid. This is what draws you back to look again at them – what keeps them present. It is a pleasure to be able to host The View from Now Here at the Eagle Gallery, and to work in collaboration with Andrew Mummery, who is a curator and gallerist for whom I have a great deal of respect. -

Scottish Art: Then and Now

Scottish Art: Then and Now by Clarisse Godard-Desmarest “Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now”, an exhibition presented in Edinburgh by the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture tells the story of collecting Scottish art. Mixing historic and contemporary works, it reveals the role played by the Academy in championing the cause of visual arts in Scotland. Reviewed: Tom Normand, ed., Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now Collected by the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, Edinburgh, The Royal Scottish Academy, 2017, 248 p. The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) have collaborated to present a survey of collecting by the academy since its formation in 1826 as the Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now (4 November 2017-7 January 2018) is curated by RSA President Arthur Watson, RSA Collections Curator Sandy Wood and Honorary Academician Tom Normand. It has spawned a catalogue as well as a volume of fourteen essays, both bearing the same title as the exhibition. The essay collection, edited by Tom Normand, includes chapters on the history of the RSA collections, the buildings on the Mound, artistic discourse in the nineteenth century, teaching at the academy, and Normand’s “James Guthrie and the Invention of the Modern Academy” (pp. 117–34), on the early, complex history of the RSA. Contributors include Duncan Macmillan, John Lowrey, William Brotherston, John Morrison, Helen Smailes, James Holloway, Joanna Soden, Alexander Moffat, Iain Gale, Sandy Wood, and Arthur Watson. -

The Magazine of the Glasgow School of Art Issue 1

Issue 1 The Magazine of The Glasgow School of Art FlOW ISSUE 1 Cover Image: The library corridor, Mackintosh Building, photo: Sharon McPake >BRIEFING Funding increase We√come Research at the GSA has received a welcome cash boost thanks to a rise in Welcome to the first issue of Flow, the magazine of The Glasgow School of Art. funding from the Scottish Higher Education Funding In this issue, Ruth Wishart talks to Professor Seona Reid about the changes and Council (SHEFC).The research challenges ahead for Scotland’s leading art school. This theme is continued by grant has risen from £365,000 to £1.3million, as a result Simon Paterson, GSA Chairman, in his interview Looking to the Future which of the Research Assessment outlines the exciting plans the School has to transform its campus into a Exercise carried out in 2001. world-class learning environment. President’s dinner A dinner to encourage Creating a world-class environment for teaching and research is essential if potential ambassadors for the GSA was held in the the GSA is to continue to contribute to Scotland, the UK and beyond. Every Mackintosh Library by Lord year 300 students graduate from the GSA and Heather Walton talks to some Macfarlane of Bearsden, the School’s Honorary President. of them about the role the GSA plays in the cultural, social and economic life In his after dinner speech, Lord of the nation. One such graduate is the artist Ken Currie, recently appointed Wilson of Tillyorn, the recently appointed Chairman of the Visiting Professor within the School of Fine Art, interviewed here by Susannah National Museums of Scotland, Thompson. -

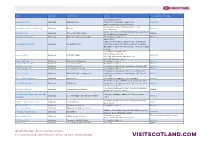

Information Correct at Time of Issue See

NAME LOCATION DESCRIPTION NOTES PLAN YOUR VISIT / BOOK Pre-booking required Craigmillar Castle Edinburgh Medieval castle Till 31st Oct: open daily, 10am to 4pm Book here Winter opening times to be confirmed. Pre-booking required. Some glasshouses closed. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Edinburgh Gardens Book here Free admission Castle closed. Free entry to the grounds (open daily 08.00- Lauriston Castle Edinburgh 16th-century tower house Walk-in 19.00) and Mimi's Cafe on site. Royal Yacht Britannia Edinburgh Attraction - former royal yacht Pre-booking recommended. Book here Shop is open Tours have been put on hold for the time being due to Edinburgh Gin Distillery Edinburgh Gin distillery tours restrictions in force from 9th Oct, and can't be booked - until further notice. Wee Wonders Online Tasting available instead. Pre-booking recommended. Currently open Thu-Mon Georgian House Edinburgh New Town House Book here 1st - 29th Nov: open Sat-Sun, 10am-4pm 30th Nov- 28th Feb: closed Edinburgh Castle Edinburgh Main castle in Edinburgh Pre-booking required. Book here Real Mary King's Close Edinburgh Underground tour Pre-booking required. Book here Our Dynamic Earth Edinburgh Earth Science Centre Pre-booking required. Open weekends in October only. Book here Edinburgh Dungeon Edinburgh Underground attraction Pre-booking required. Book here Pre-booking recommended. The camera show is not Camera Obscura Edinburgh World of Illusions - rooftop view running at the moment - admission price 10% lower to Book here reflect this. Palace of Holyroodhouse Edinburgh Royal Palace Pre-booking recommended. Open Thu-Mon. Book here Pre-booking required. Whisky is not consumed within Scotch Whisky Experience Edinburgh Whisky tours the premises for now, instead it's given at the end of Book here the tours to take away. -

Histoire Des Collections Numismatiques Et Des Institutions Vouées À La Numismatique

HISTOIRE DES COLLECTIONS NUMISMATIQUES ET DES INSTITUTIONS VOUÉES À LA NUMISMATIQUE Numismatic Collections in Scotland Scotland is fortunate in possessing two major cabinets of international signifi- cance. In addition over 120 other institutions, from large civic museums to smaller provincial ones, hold collections of coins and medals of varying size and impor- tance. 1 The two main collections, the Hunterian held at the University of Glasgow, and the national collection, housed at the National Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh, nicely complement each other. The former, based on the renowned late 18th centu- ry cabinet of Dr. William Hunter, contains an outstanding collection of Greek and Roman coins as well as important groups of Anglo-Saxon, medieval and later English, and Scottish issues along with a superb holding of medals. The National Museums of Scotland house the largest and most comprehensive group of Scottish coins and medals extant. Each collection now numbers approximately 70,000 speci- mens. The public numismatic collections from the rest of Scotland, though perhaps not so well known, are now recorded to some extent due to a National Audit of the coun- try’s cultural heritage held by museums and galleries carried out by the Scottish Museums Council in 2001 on behalf of the Scottish Government. 2 Coins and Medals was one of 20 collections types included in the questionnaire, asking for location, size and breakdown into badges, banknotes, coins, medals, tokens, and other. Over 12 million objects made up what was termed the Distributed National Collection, of which 3.3% consisted of approximately 68,000 coins and medals in the National Museums concentrated in Edinburgh and 345,000 in the non-nationals throughout the rest of the country. -

Mark Fairnington Unnatural History

Mark Fairnington UnnaturalMarkFairningtonHistory Mannheimer Kunstverein Mark Fairnington Galerie Peter Zimmermann Mannheimer KunstvereinMannheimer GaleriePeter/ Zimmermann Unnatural History Mark Fairnington Unnatural History 1 Mark Fairnington Unnatural History 2 3 Published on the occasion of 6 The Observing Eye Unnatural History 8 Das beobachtende Auge at Mannheimer Kunstverein and Galerie Peter Zimmermann 11 Specimens in February 2012 29 Paradise Birds 22 Interview with Darian Leader by Mannheimer Kunstverein e.V. Augustaanlage 58 D-68165 Mannheim, Germany 39 Bulls www.mannheimer-kunstverein.de 50 Im Gespräch mit Darian Leader and Galerie Peter Zimmermann Leibnizstraße 20 D-68165 Mannheim, Germany 57 Flora www.galerie-zimmermann.de 69 Eyes with design – Jaakko / Supergroup Studios 80 How can I move thee? photography – Peter White, Simon Steven & ??? ??? english translation – Amy Klement german translation – Catrin Huber 83 Displays print – Die Keure, Brugge, Belgium 92 Wie kann ich Sie? © Peter Zimmerman Gallery, Mark Fairnington and FXP Photography ISBN 978-3-9808352-9-9 95 Storage 106 Curriculum Vitae 108 Acknowledgements 4 5 The Observing Eye Martin Stather “The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are causes a pulling away, that maintains a distance blocks of stone, finishes off her sketches, signs them with particularly unique. Although not portraits in the attentive and wary. The same animal may well look between the subject of the painting and the viewer. his stamp, impresses on them his artistic hall-mark.” conventional sense, these images are, nonetheless, at other species in the same way. He does not reserve The living now seems lifeless, excised from the (Huysmans, 1884) distinctive in their portrayal and in the respect a special look for man. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning.