Racing Toward History: Utopia and Progress in John Guare's a Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

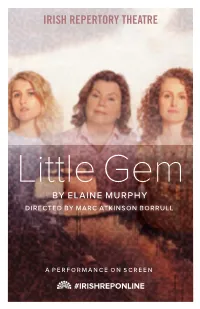

Digital Playbill

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE Little Gem BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN LITTLE GEM BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL STARRING BRENDA MEANEY, LAUREN O'LEARY AND MARSHA MASON scenic design costume design lighting design sound design & original music sound mix MEREDITH CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL RYAN M.FLORIAN RIES METZGER O'CONNOR RUMERY STAAB edited by production coordinator production coordinator SARAH ARTHUR REBECCA NICHOLS ATKINSON MONROE casting press representatives general manager DEBORAH BROWN MATT ROSS LISA CASTING PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE North Dublin, 2008 Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission. SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre wishes to thank Henry Clarke, Olivia Marcus, Melanie Spath, and the Howard Gilman Foundation. Little Gem is produced under the SAG-AFTRA New Media Contract. THE ORIGINAL 2019 PRODUCTION OF LITTLE GEM ALSO FEATURED PROPS BY SVEN HENRY NELSON AND SHANNA ALISON AS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST MARSHA MASON (Kay) has summer 2019, Marsha starred in Irish received an Outer Critics Rep’s acclaimed production of Little Gem Circle Award and 4 Academy and directed a reading of The Man Who Awards nominations for her Came to Dinner with Brooke Shields and roles in the films “The Goodbye Walter Bobbie at the Bucks County Girl,” “Cinderella Liberty,” Playhouse and WP Theater in NYC. -

Program from the Production

STC Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Stephen A. Hopkins Emeritus Trustees Michael R. Klein, Chair Lawrence A. Hough R. Robert Linowes*, Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair W. Mike House Founding Chairman John Hill, Treasurer Jerry J. Jasinowski James B. Adler Pauline Schneider, Secretary Norman D. Jemal Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Scott Kaufmann David A. Brody* Kevin Kolevar Melvin S. Cohen* Trustees Abbe D. Lowell Ralph P. Davidson Nicholas W. Allard Bernard F. McKay James F. Fitzpatrick Ashley M. Allen Eleanor Merrill Dr. Sidney Harman* Stephen E. Allis Melissa A. Moss Lady Manning Anita M. Antenucci Robert S. Osborne Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Stephen M. Ryan William F. McSweeny Afsaneh Beschloss K. Stuart Shea V. Sue Molina William C. Bodie George P. Stamas Walter Pincus Landon Butler Lady Westmacott Eden Rafshoon Dr. Paul Carter Rob Wilder Emily Malino Scheuer* Chelsea Clinton Suzanne S. Youngkin Lady Sheinwald Dr. Mark Epstein Mrs. Louis Sullivan Andrew C. Florance Ex-Officio Daniel W. Toohey Dr. Natwar Gandhi Chris Jennings, Sarah Valente Miles Gilburne Managing Director Lady Wright Barbara Harman John R. Hauge * Deceased 3 Dear Friend, Table of Contents I am often asked to choose my favorite Shakespeare play, and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 Title Page 5 it is very easy for me to answer immediately Henry IV, Parts 1 The Play of History and 2. In my opinion, there is by Drew Lichtenberg 6 no other play in the English Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 1 9 language which so completely captures the complexity and Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 2 10 diversity of an entire world. -

Title: Title: Title

Title: 45 Seconds from Broadway Author: Simon, Neil Publisher: Samuel French 2003 Description: roy comedy - friendship - Broadway twelve characters six male; six female two acts interior set; running time: more than 120 minutes; 1 setting From America's master of Contemporary Broadway Comedy, here is another revealing comedy behind the scenes in the entertainment world, this time near the heart of the theatre district. 45 Seconds from Broadway takes place in the legendary "Polish Tea Room" on New York's 47th Street. Here Broadway theatre personalities washed-up and on-the-rise, gather to schmooz even as they Title: Aberhart Summer, The Author: Massing, Conni Publisher: NeWest Press 1999 Description: roy comedy - historical - Alberta playwright - Canadian eleven characters eight male; three female two acts "Based on Bruce Allen Powe's 1984 novel [of the same name], Massing's marvelous play is at once a gripping Alberta history lesson, a sweetly nostalgic comedy and a cracking-good-murder-mystery, all rolled up into one big, bright ball of theatrical energy and verve..." Calgary Herald "At its best, Aberhart Summer is a vivid and unsentimental depiction of small-town Canadian life in Title: Accidents Happen Seven short plays Author: DeAngelis, J. Michael Barry, Pete Publisher: Samuel French 2010 Description: roy comedy large cast flexible casting seven one acts Seven of The Porch Room's best short plays collected together into an evening of comedy that proves that no matter what you plan for - accidents happen. The shorts can be performed together as a full-length show or on their own as one acts. -

Class of 1965 50Th Reunion

CLASS OF 1965 50TH REUNION BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1965 Abby Goldstein Arato* June Caudle Davenport Anna Coffey Harrington Catherine Posselt Bachrach Margo Baumgarten Davis Sandol Sturges Harsch Cynthia Rodriguez Badendyck Michele DeAngelis Joann Hirschorn Harte Isabella Holden Bates Liuda Dovydenas Sophia Healy Helen Eggleston Bellas Marilyn Kirshner Draper Marcia Heiman Deborah Kasin Benz Polly Burr Drinkwater Hope Norris Hendrickson Roberta Elzey Berke Bonnie Dyer-Bennet Suzanne Robertson Henroid Jill (Elizabeth) Underwood Diane Globus Edington Carol Hickler Bertrand* Wendy Erdman-Surlea Judith Henning Hoopes* Stephen Bick Timothy Caroline Tupling Evans Carla Otten Hosford Roberta Robbins Bickford Rima Gitlin Faber Inez Ingle Deborah Rubin Bluestein Joy Bacon Friedman Carole Irby Ruth Jacobs Boody Lisa (Elizabeth) Gallatin Nina Levin Jalladeau Elizabeth Boulware* Ehrenkranz Stephanie Stouffer Kahn Renee Engel Bowen* Alice Ruby Germond Lorna (Miriam) Katz-Lawson Linda Bratton Judith Hyde Gessel Jan Tupper Kearney Mary Okie Brown Lynne Coleman Gevirtz Mary Kelley Patsy Burns* Barbara Glasser Cynthia Keyworth Charles Caffall* Martha Hollins Gold* Wendy Slote Kleinbaum Donna Maxfield Chimera Joan Golden-Alexis Anne Boyd Kraig Moss Cohen Sheila Diamond Goodwin Edith Anderson Kraysler Jane McCormick Cowgill Susan Hadary Marjorie La Rowe Susan Crile Bay (Elizabeth) Hallowell Barbara Kent Lawrence Tina Croll Lynne Tishman Handler Stephanie LeVanda Lipsky 50TH REUNION CLASS OF 1965 1 Eliza Wood Livingston Deborah Rankin* Derwin Stevens* Isabella Holden Bates Caryn Levy Magid Tonia Noell Roberts Annette Adams Stuart 2 Masconomo Street Nancy Marshall Rosalind Robinson Joyce Sunila Manchester, MA 01944 978-526-1443 Carol Lee Metzger Lois Banulis Rogers Maria Taranto [email protected] Melissa Saltman Meyer* Ruth Grunzweig Roth Susan Tarlov I had heard about Bennington all my life, as my mother was in the third Dorothy Minshall Miller Gail Mayer Rubino Meredith Leavitt Teare* graduating class. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual 2017 Report Our ongoing investment into increasing services for the senior In 2017, The Actors Fund Dear Friends, members of our creative community has resulted in 1,474 senior and helped 13,571 people in It was a challenging year in many ways for our nation, but thanks retired performing arts and entertainment professionals served in to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, stronger 2017, and we’re likely to see that number increase in years to come. 48 states nationally. than ever. Our increased activities programming extends to Los Angeles, too. Our programs and services With the support of The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, The Actors Whether it’s our quick and compassionate response to disasters offer social and health services, Fund started an activities program at our Palm View residence in West ANNUAL REPORT like the hurricanes and California wildfires, or new beginnings, employment and training like the openings of The Shubert Pavilion at The Actors Fund Hollywood that has helped build community and provide creative outlets for residents and our larger HIV/AIDS caseload. And the programs, emergency financial Home (see cover photo), a facility that provides world class assistance, affordable housing 2017 rehabilitative care, and The Friedman Health Center for the Hollywood Arts Collective, a new affordable housing complex and more. Performing Arts, our brand new primary care facility in the heart aimed at the performing arts community, is of Times Square, The Actors Fund continues to anticipate and in the development phase. provide for our community’s most urgent needs. Mission Our work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. -

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM Presents MACBETH by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM presents MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE WITH BARZIN AKHAVAN, RAFFI BARSOUMIAN, NADIA BOWERS, N’JAMEH CAMARA, ERIK LOCHTEFELD, MARY BETH PEIL, COREY STOLL, BARBARA WALSH, ANTONIO MICHAEL WOODARD COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN ANN HOULD-WARD SOLOMON WEISBARD MATT STINE FIGHT DIRECTOR PROPS SUPERVISOR THOMAS SCHALL ALEXANDER WYLIE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN SOUND DESIGN DAVID L. ARSENAULT AMY PRICE AJ SURASKY-YSASI PRESS PRODUCTION CASTING REPRESENTATIVES STAGE MANAGER TELSEY + COMPANY BLAKE ZIDELL AND BERNITA ROBINSON KARYN CASL, CSA ASSOCIATES ASSISTANT DESTINY LILLY STAGE MANAGER JESSICA FLEISCHMAN DIRECTED AND DESIGNED BY JOHN DOYLE MACBETH (in alphabetical order) Macduff, Captain ............................................................................ BARZIN AKHAVAN Malcolm ......................................................................................... RAFFI BARSOUMIAN Lady Macbeth ....................................................................................... NADIA BOWERS Lady Macduff, Gentlewoman ................................................... N’JAMEH CAMARA Banquo, Old Siward ......................................................................ERIK LOCHTEFELD Duncan, Old Woman .........................................................................MARY BETH PEIL Macbeth..................................................................................................... -

Asides Magazine

2014|2015 SEASON Issue 5 TABLE OF Dear Friend, Queridos amigos: CONTENTS Welcome to Sidney Harman Bienvenidos al Sidney Harman Hall y a la producción Hall and to this evening’s de esta noche de El hombre de La Mancha. Personalmente, production of Man of La Mancha. 2 Title page The opening line of Don esta obra ocupa un espacio cálido pero enreversado en I have a personally warm and mi corazón al haber sido testigo de su nacimiento. Era 3 Musical Numbers complicated spot in my heart Quixote is as resonant in el año 1965 en la Casa de Opera Goodspeed en East for this show, since I was a Latino cultures as Dickens, Haddam, Connecticut. Estaban montando la premier 5 Cast witness to its birth. It was in 1965, at the Goodspeed Twain, or Austen might mundial, dirigida por Albert Marre. Se suponía que Opera House in East Haddam, CT. They were Albert iba a dirigir otra premier para ellos, la cual iba 7 About the Author mounting the world premiere, directed by Albert be in English literature. a presentarse en repertorio con La Mancha, pero Albert Marre. Now, Albert was supposed to direct another 10 Director’s Words world premiere for them, which was going to run In recognition of consiguió un trabajo importante en Hollywood y les recomendó a otro director: a mí. 12 The Impossible Musical in repertory with La Mancha, but he got a big job in Cervantes’ legacy, we at Hollywood, and he recommended another director. by Drew Lichtenberg That was me. STC want to extend our Así que fui a Goodspeed y dirigí la otra obra. -

Elgin Academy's Summer Theater Program Is Excited to Be Hosting

Elgin Academy’s Summer Theater Program is excited to be hosting educators Rick Hilsabeck and Sarah Pfisterer, award winning Broadway Stars from The Phantom of the Opera, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Billy Elliot and Show Boat! Rick Hilsabeck is a highly regarded actor, singer, dancer and teacher with over 35 years of experience starring on Broadway, national tours, the concert stage, as well as the dance world. He has enjoyed a successful and diverse international career. Rick learned the hallmarks of good teaching from his parents. His mom, an accomplished soprano in her own right, and his dad, a beloved high school history teacher, recognized his growing interests in art, music and dance. With a solid foundation early on in vocal technique and an interest in dance, he was pointed in the right direction. Directly out of high school, Rick was chosen to be a member of the Academy Award winning singing group The Young Americans, based in Los Angeles. He was also accepted to the Acting program at California State University, Fullerton. There he studied all aspects of the theatre arts: acting technique, scene study, makeup design, set design, fencing, stage combat and mime. Rick returned to his native Chicago where he worked in the area theatres and studied dance with Lou Conte. The internationally acclaimed Hubbard Street Dance Company was in its infancy at the time and Rick became the first male principal dancer with the troupe where he appeared in two PBS TV specials. He had a long tenure with HSDC as a dancer, choreographer and teacher. -

OCC D 6 Theat Eee 1305 1B E

r this cover and their final version of the extended essay to is are is a not use Examiner 1 Examiner 2 Examiner 3 A research 2 2 B introduction 2 2 c 4 D 4 D 4 4 E reasoned 4 4 D F and evaluation 4 4 G use of 4 D 4 conclusion 2 2 formal 4 4 J abstract 2 2 holistic 4 4 Which techniques of Bob Fosse influenced and led to the revitalization of Broadway musicals of the 1970's? Subject: Theatre Advisor: International Baccalaureate Extended Essay Word Count: 3,933 Page 1 of 18 Abstract In this extended essay I researched the question of which techniques of famous choreographer Bob Fosse influenced the Broadway musicals of the 1970's. Through his effective techniques of innovative choreography and story-telling, Fosse revolutionized the American Broadway industry. I specifically analyzed the popular musicals Chicago, Sweet Charity, and Pippin to support this thesis. In order to investigate my topic, I watched stage productions of these three musicals. I also went to a live production of Chicago at a local theatre, Players by the Sea. It was beneficial to see these productions because I could analyze the choreography first-hand. And I could see how it worked alongside with the story-telling. However, these productions were not Fosse's originals, but they only showed how influential his techniques had become. I also began researching information about the Broadway industry in the 1970's. I discovered articles about lost elements of choreography, as well as reviews on Fosse's work. -

Mcmartin Family

Outline Descendant Report for John McMartin ..... 1 John McMartin b: Abt. 1755 in Killin, Perthshire, Scotland, d: Aft. 1806 in Martintown, Charlottenburgh, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada, AltName: ; John MacMartin, Relationship: A younger brother of Malcolm Sr. named John was with them. He married Ellen Cameron at Caughnawaga near Johnstown in 1778 an founded the Big John and Big Malcolm and Big Allan, Relationship: The Big Johns, the Big Malcolms, and the Big Allans of the Hollinger mine are descended from John & Ellen, Immigrated: 1773 ; Came to America on the Pearl. Settled in Mohawk Valley, New York, Military: ; the war in the Engineers Dept. Served in the Kings Royal Regiment of NY as a Sergeant in Kings Works., Residence: ; Martintown, Glengarry, Ontario, Residence: ; Conc 1, Lot 23, SSRR, and bought Lot 25 in the same concession from Patrick O'Hales., Residence: Aft. 1773 ; Tryon County, New York, USA, Residence: ; of Letterfinay ..... + Ellen Cameron b: 1759 in Inverness, Scotland, b: 15 Jun 1765 in Petty, Inverness, Scotland, m: 18 Oct 1779 in Fonda, Montgomery, New York, m: 1778 in Fonda, Montgomery City, New York, d: 25 Aug 1851 in Martintown, Charlottenburgh, Glengarry, Canada, Also Known As: Nelly Cameron, AltName: ; Helen Cameron, AltName: ; Nelly Cameron, Residence: Bet. 1797–18 May 1806 ; Charlottenburgh, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada ........... 2 Mary McMartin b: Abt. 1781 in Martintown, Charlottenburgh, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada ........... + Duncan Grant b: 1777 in Kingsborough Patent, New York, USA, m: 17 Dec 1799 in St. Andrew's Pres., Williamstown, , Glengarry, Ontario, Canada, d: 14 May 1836 in Conc 2, Lot 36, Kenyon, Apple Hill, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada, Relationship: Mary married Duncan Grant brother of Peter and son of Angus. -

A Moo Moo Here and a Moo Moo There - the Ne

THEATER; A Moo Moo Here and a Moo Moo There - The Ne... http://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/28/theater/theater-a-moo-moo... This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, please click here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. » April 28, 2002 THEATER THEATER; A Moo Moo Here and a Moo Moo There By BARRY SINGER YOU might say that the musical revival of ''Into the Woods,'' opening on Tuesday at the Broadhurst Theater, has been re-embroidered rather than re-invented. Though the sets and costumes are derived from the original 1987 Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine collection of classic fairy tales, they are newly conceived, as is Mr. Lapine's directorial view of certain characters. ''The attitude this time is definitely different,'' said Mr. Sondheim, who has reworked a lyric or two. One song, written for a later London production, has been added, ''Our Little World.'' ''The cast makes a huge difference in terms of tone,'' Mr. Sondheim said, ''and James has had many new ideas.'' In addition to the Narrator (John McMartin), the characters are the same, among them: the Witch (Vanessa Williams), Cinderella (Laura Benanti) and her Prince (Gregg Edelman), the Baker (Stephen DeRosa), Little Red Ridinghood (Molly Ephraim) and Jack, of beanstalk fame (Adam Wylie). Then there is the cow. Jack's pet, Milky-White, was a scrawny statue with handgrips that actors lugged around the stage like a suitcase in 1987. -

To Download The

NEWS Local news and entertainment since 1969 GET SOLAR & AC Entertainment AND SAVE BIG SAVE YOUR ELECTRIC BILL EACH MONTH 25 YEAR WARRANTY August 7 - 13, 2020 $89.94 COMBINED Guide A MONTH Election season Amana Lifetime Warranty Last AC You’ll Ever Inside is upon us Buy ‘Air Jaws’ – Lic #380200 • 4.38 kw • $36,000 financed at 2.99% is combo price $89.94 for pages 3, 14 20 years of sharks in flight 18 months then re-amortize OAC. Shark Week begins 575-449-3277 Sunday on Discovery. YELLOWBIRDAC.COM • YELLOWBIRDSOLAR.COM2 x 5.5” ad FRIDAY, AUGUST 7, 2020 Explore Southern New Mexico Explore the monthly Desert Exposure, “the biggest little Here are some ways to get your Desert Exposure fix: newspaper in the Southwest.” This eclectic arts and leisure • Check area racks and newsstands • Share stories and photos publication delivers a blend of content to make you laugh, with Editor Elva Osterreich I Volume 52, Number 32 • Visit www.desertexposure.com think and sometimes just get up and dance. [email protected], • Sign up for an annual mail subscription 575-443-4408 Desert Exposure captures the flavor, beauty and for $54 contact Teresa Tolonen, • Promote your organization to uniqueness of Silver City, Las Cruces and the whole [email protected], NEWS I lascrucesbulletin.com our widespread readership Southwest region of New Mexico. You can also peruse or call 575-680-1841 through Desert Exposure our wide array of advertisers to plan your stops on your • Sign up for our semi-monthly advertising with Pam Rossi next Southwest New Mexico road trip, no matter which Desert Exposure email newsletter [email protected], direction you’re going.