Implementation of the Tallinn Charter: Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tallinn Facts & Figures 09

TALLINN - HOME fOr BUSINESS TALLINN FACTS & FIGURES 09 rEPUBLIC Of ESTONIA 3 TALLINN 4 POPULATION 7 LABOUr MArKET 10 ECONOMY 12 BUSINESS ACTIVITIES 18 TOUrISM 22 fOrEIGN TrADE 25 HOUSING AND rEAL ESTATE 27 TrANSPOrT 29 COMMUNICATIONS 31 HEALTH CArE AND SOCIAL CArE 35 EDUCATION 36 CULTUrE 38 ENVIrONMENT 40 TALLINN’S BUDGET 41 Published by: Tallinn City Enterprise Board (www.investor.tallinn.ee) Design: Ecwador Advertising Photos: Toomas Volmer, Triin Abel, Karel Koplimets, Toomas Tuul, Meelis Lokk, Maido Juss, Arno Mikkor, Kärt Kübarsepp, Kaido Haagen, Harri rospu, Andreas Meichsner, Meeli Tulik, Laulasmaa resort, Arco Vara, Tallinn Airport, IB Genetics OÜ, Port of Tallinn Print: folger Art TALLINN - HOME fOr BUSINESS 03 REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA Area 45 227 km2 Climate Average temperature in July +16.7° C (2008) Average temperature in February -4° C (2009) Population 1,340,341 (1 January 2009) Time zone GMT +2 in winter GMT +3 in summer Language Estonian Currency Estonian kroon (EEK) 1 EEK = 100 cents 1 EUR = 15.6466 EEK As of May 1, 2004, Estonia is a European Union member state. As of March 29, 2004, Estonia is a full member of NATO. As of December 21, 2007, Estonia belongs to the Schengen Area. 04 TALLINN Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, is located in Northern Europe in the northeast part of the Baltic Sea Region, on the coast of the Gulf of Finland. A favourable geographic location has helped Tallinn develop into a port city, as well as an industrial and commercial centre. Tallinn, a well-known Hanseatic town, received its township rights in 1248. -

News from Copenhagen

News from Copenhagen Number 423 Current Information from the OSCE PA International Secretariat 29 February 2012 Prisons, economic crisis and arms control focus of Winter Meeting The panel of the General Committee on Democracy, Human The panel of the General Committee on Economic Affairs, Rights and Humanitarian Questions on 23 February. Science, Technology and Environment on 23 February. The 11th Winter Meeting of the OSCE Parliamentary the vice-chairs on developments related to the 2011 Belgrade Assembly opened on 23 February in Vienna with a meeting Declaration. of the PA’s General Committee on Democracy, Human Rights The Standing Committee of Heads of Delegations met on and Humanitarian Questions, in which former UN Special 24 February to hear reports of recent OSCE PA activities, as Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak took part, along with well as discuss upcoming meetings and election observation. Bill Browder, Eugenia Tymoshenko, and Iryna Bogdanova. After a discussion of the 4 March presidential election in Committee Chair Matteo Mecacci (Italy) noted the impor- Russia, President Efthymiou decided to deploy a small OSCE tance of highlighting individual stories to “drive home the PA delegation to observe. urgency of human rights.” In this regard, Browder spoke Treasurer Roberto Battelli presented to the Standing Com- about the case of his former attorney, the late Sergei Magnit- mittee the audited accounts of the Assembly for the past finan- sky, who died in pre-trial detention in Russia. cial year. The report of the Assembly’s outside independent Eugenia Tymoshenko discussed the case of her mother, professional auditor has given a positive assessment on the former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, cur- PA´s financial management and the audit once again did not rently serving a seven-year prison sentence. -

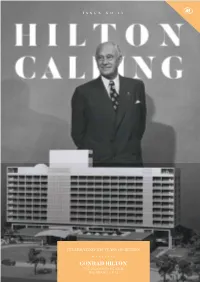

CONRAD HILTON the VISIONARY BEHIND the BRAND – P.12 Visit → Businessventures.Com.Mt

ISSUE NO.13 CELEBRATING 100 YEARS OF HILTON CONRAD HILTON THE VISIONARY BEHIND THE BRAND – P.12 Visit → businessventures.com.mt Surfacing the most beautiful spaces Marble | Quartz | Engineered Stone | Granite | Patterned Tiles | Quartzite | Ceramic | Engineered Wood Halmann Vella Ltd, The Factory, Mosta Road, Lija. LJA 9016. Malta T: (+356) 21 433 636 E: [email protected] www.halmannvella.com Surfacing the most beautiful spaces Marble | Quartz | Engineered Stone | Granite | Patterned Tiles | Quartzite | Ceramic | Engineered Wood Halmann Vella Ltd, The Factory, Mosta Road, Lija. LJA 9016. Malta T: (+356) 21 433 636 E: [email protected] www.halmannvella.com FOREWORD Hilton Calling Dear guests and friends of the Hilton Malta, Welcome to this very special edition of our magazine. The 31st of May 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the opening of the first Hilton hotel in the world, in Cisco, Texas, in the United States of America. Since that milestone date in 1919, the brand has gone from strength to strength. Globally, there are currently just under 5700 hotels, in more than 100 countries, under a total of 17 brands, with new properties opening every day. Hilton has been EDITOR bringing memorable experiences to countless guests, clients and team members Diane Brincat for a century, returned value to the owners who supported it, and made a strongly positive impact on the various communities in which it operates. We at the Hilton MAGAZINE COORDINATOR Malta are proud to belong to this worldwide family, and to join in fulfilling its Rebecca Millo mission – in Conrad Hilton’s words, to ‘fill the world with the light and warmth of hospitality’ – for at least another 100 years. -

Voyager of the Seas® - 2022 Europe Adventures

Voyager of the Seas® - 2022 Europe Adventures Get your clients ready to dive deep into Europe in Summer 2022. They can explore iconic destinations onboard the new Odyssey of the Seas S M. Fall in love with the Med's greatest hits and discover its hidden gems onboard Voyager of the Seas® ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 9-Night Best of Western April 15, 2022 Barcelona, Spain • Cartagena, Spain • Gibraltar, Europe United Kingdom • Cruising • Lisbon, Portugal • Cruising (2 nights) • Amsterdam, Netherlands Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Best of Northern April 24, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Oslo, Norway Europe August 28, 2022 (Overnight) • Kristiansand, Norway • Cruising • Skagen, Denmark • Gothenburg, Sweden • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & May 1, 8, 15, 22, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Russia Sweden • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia • Helsinki, Finland • Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & May 29, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Russia Sweden • Helsinki, Finland • St. Petersburg, Russia • Tallinn, Estonia • Copenhagen, Denmark 10-Night Scandinavia & June 5, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Russia Sweden • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia (Overnight) • Helsinki, Finland • Riga, Latvia • Visby, Sweden • Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark Book your Europe adventures today! Features vary by ship. All itineraries are subject to change without notice. ©2020 Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. Ships’ registry: The Bahamas. 20074963 • 11/24/2020 ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 11-Night Scandinavia & June 15, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Ronne, Bornholm, Russia Denmark • Cruising • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia (Overnight) • Helsinki, Finland • Visby, Sweden • Riga, Latvia • Cruising (2-Nights) • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & July 3, 2022 Stockholm, Sweden• Cruising • St. -

View Adventure of the Seas 2021 European Sailings

Adventure of the Seas® Get ready to dive deeper into Old World adventures in Summer 2021. Rediscover the Med’s greatest hits onboard Harmony of the Seas® , sailing from Barcelona and Rome, or on returning favorites Vision® and Rhapsody of the Seas® . Head north for unforgettable sights in the Baltics and the British Isles onboard Jewel of the Seas® . Choose from fjord filled thrills in Norway to Mediterranean marvels and everywhere in between onboard Anthem of the Seas® , sailing from Southampton —all open to book now. ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 18-Night Galveston to April 21, 2021 Galveston, Texas • Cruising (9 Nights) • Gran Canaria, Copenhagen Canary Islands • Cruising • Lisbon, Portugal • Cruising (2 Nights) • Paris (Le Havre), France • Rotterdam, Netherlands • Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & May 16, 2021 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Sweden Russia • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia • Cruising (2 Nights) • Copenhagen, Denmark 8-Night Scandinavia & May 30, 2021 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Sweden Russia • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia • Helsinki, Finland • Cruising (2 Nights) • Copenhagen, Denmark 10-Night Scandinavia & June 7, 2021 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Riga, Latvia • Russia Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia (Overnight) • Helsinki, Finland • Stockholm, Sweden • Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark (Overnight) 10-Night Ultimate June 17, 2021 Copenhagen, Denmark • Berlin (Warnemunde), Scandinavia Adventure Germany • Cruising • Helsinki, Finland • St. Petersburg, Russia (Overnight) • Tallinn, Estonia • For deployment information and marketing resources, visit LoyalToYouAlways.com/Deployment Features vary by ship. All itineraries are subject to change without notice. ©2019 Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. Ships’ registry: The Bahamas. ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL Visby, Sweden • Riga, Latvia • Stockholm, Sweden (Overnight) 7-Night Scandinavia & June 27, 2021 Stockholm, Sweden • Cruising • St. -

BUSINESS NEWS of the ISSUER NIS A.D. NOVI SAD Oil Major NIS

BUSINESS NEWS OF THE ISSUER NIS A.D. NOVI SAD Oil major NIS first company from Serbia to open representation in Brussels NIS celebrated the opening of its corporate representation to the European Union on 23 June 2011. The festive launch ceremony was hosted by the top management of NIS and its main shareholders, Minister of Foreign Affairs Vuk Jeremic on behalf of Serbian government, and permanent representative of Russian Federation to the EU Vladimir Chizhov. The event gathered officials from EU institutions as well as peers and stakeholders. NIS is the first company from Serbia to open a permanent business representation in Brussels. Mr. Kirill Kravchenko, CEO of NIS, said: ”The EU is of strategic importance for the economic development of Serbia. This is why NIS and its main shareholders – the Serbian government and Gazprom Neft – are keen to initiate a permanent dialogue between the Serbian oil and gas sector and the European institutions. NIS supports the economic integration and political accession of Serbia to the EU and has realised enormous investments in order to adapt its facilities to EU standards – for example by modernising its refinery in Pancevo. In addition, NIS already has the institutional European investors. This year the company has started realization of the projects in EU countries – Romania and Hungary-, our first step as a contribution to the development of the EU economy. By entering the EU market we create jobs, revenues, develop technology and partnerships with the largest European companies. Our new representation in Brussels will help us to complement this process through a constructive dialogue with EU decision-makers.” The opening of a representation in Brussels is a part of NIS’ business strategy to reach a leading position in the oil and gas sector of the region by applying EU standards and the most advanced technologies in its business operations. -

December 2019 Vladimir J. Konečni

December 2019 Vladimir J. Konečni CURRICULUM VITAE Birthplace: Belgrade, Yugoslavia Citizenship: Serbia and U.S.A. Address: Department of Psychology University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92093-0109, U.S.A. Office: tel (858) 534-3000; e-mail [email protected] Residence: tel (858) 481-9719 Web sites: http://www.vladimirkonecni.net/VJK_Publications http://psychology.ucsd.edu/people/profiles/vkonecni.html http://www.vladimirkonecni.net https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_J._Konečni Education: 1959-1963 Second Belgrade Gymnasium, Belgrade, Yugoslavia 1964-1969 University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia; Diploma in Experimental and Clinical Psychology, 1969 1968 Behavior Modification Section, Academic Unit of Psychiatry, Middlesex Hospital, London, England 1970-1973 University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; M.A., 1971; Ph.D., 1973 (Social and Experimental Psychology) Graduate Fellowships: 1970-1971 University of Toronto Open Fellowship; M. H. Beatty Graduate Fellowship 1971-1973 Canada Council Doctoral Fellowship 1972-1973 Junior Fellowship, Massey (Graduate) College, University of Toronto Research Fellowships: 1979-1980 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship 1987 Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD; September, December) Honors: 1994 Academician (Active Member, Section of Informatics in Culture) of the International Informatics Academy (Moscow/New York, an Affiliate of the Organization of United Nations); elected in September of 1994 in Moscow Academic Positions: 2 1973-1978 Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, -

Vienna International Centre

Terms of Reference Organisational Section/Unit : UNODC, Brussels Liaison Office Office Phone: 0032 2 290 25 80 Duty Station: Brussels, Belgium Supervisor: Ms Yatta Dakowah, Representative and Chief of the Office Duration: 3 to 6 months (with a preference for 6 months) Starting time: Monday 3 September 2018 Deadline for application: Friday 17 August 2018 The main eligibility criteria for the UNOV/UNODC internship programme are: - Interns may be accepted provided that one of the following conditions is met: ✓ The applicant must be enrolled in a graduate school programme (second university degree or equivalent, or higher); ✓ The applicant must be enrolled in the final academic year of a first university degree programme (minimum Bachelor’s level or equivalent); ✓ The applicant must have graduated with a university degree (as defined above) and, if selected, must commence the internship within a one-year period of graduation; - A person who is the child or sibling of a staff member shall not be eligible to apply for an internship at the United Nations. An applicant who bears to a staff member any other family relationship may be engaged as an intern provided that he or she shall not be assigned to the same work unit of the staff member nor placed under the direct or indirect supervision of the staff member. More information on the UNODC Internship Programme website. Background information: The tasks of the UNODC Brussels Liaison Office are as follows: ✓ Enhancing and fostering partnerships with European Union institutions, in particular with the European Commission, and strengthening policy exchange and dialogue with key partners such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the World Customs Organization and the United Nations system present in Brussels; ✓ Increasing understanding of the work of UNODC related to drugs, crime and terrorism by promoting health, justice and security within the European Union and to a wider public; ✓ Promoting UNODC and the impact of our work to Brussels-based think tanks, NGOs, associations, universities and the general public. -

16. Stockholm & Brussels 1911 & 1912: a Feminist

1 16. STOCKHOLM & BRUSSELS 1911 & 1912: A FEMINIST INTERNATIONAL? You must realize that there is not only the struggle for woman Suffrage, but that there is another mighty, stormy struggle going on all over the world, I mean the struggle on and near the labour market. Marie Rutgers-Hoitsema 1911 International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) became effective because it concentrated on one question only. The Alliance (it will be the short word for the IWSA) wanted to show a combatant and forceful image. It was of importance to have many followers and members. Inside the Alliance, there was no room to discuss other aspect of women's citizenship, only the political. This made it possible for women who did not want to change the prevalent gender division of labor to become supporters. The period saw an increase of the ideology about femininity and maternity, also prevalent in the suffrage movement. But some activists did not stop placing a high value on the question of woman's economic independence, on her economic citizenship. They wanted a more comprehensive emancipation because they believed in overall equality. Some of these feminists took, in Stockholm in 1911, the initiative to a new international woman organization. As IWSA once had been planned at an ICW- congress (in London in 1899) they wanted to try a similar break-out-strategy. IWSA held its sixth international congress in June in the Swedish capital. It gathered 1 200 delegates.1 The organization, founded in opposition to the shallow enthusiasm for suffrage inside the ICW, was once started by radical women who wanted equality with men. -

Brussels, January 9, 2007

Brussels, January 10, 2007 Rezidor opens two new Park Inn hotels in Sweden and UK The Rezidor Hotel Group has signed agreements for 2 more Park Inn hotels in Sweden and UK – namely in the Swedish capital Stockholm, and in Leigh, Great Britain. The new Park Inn hotel in Stockholm, which is to be built in the rapidly growing area known as Hammarby Sjostad, will comprise 177 rooms, is scheduled to open in 2009 and will be the 16th Park Inn in Sweden. The 18-storey property will have a roof top terrace and a relax centre on the top floor, and will be a landmark in the area. Owner and constructor is Botrygg Bygg AB. The new hotel is in line with Rezidor’s strategy to pursue aggressive expansion within the mid market segment. “Park Inn is an important part of our growth strategy, as is the Swedish market where there is strong demand for mid market hotels,” says Kurt Ritter, President & CEO of The Rezidor Hotel Group. In June last year, Rezidor announced the new Park Inn Congress Centre Stockholm with 420 rooms in the very heart of Stockholm, scheduled to open in 2010. The property is a much awaited hotel and congress centre with capacity for up to 3.000 delegates in an auditorium setting, placing Stockholm among an exclusive group of global cities offering similar congress facilities in their city centre. The Park Inn Leigh will be built on the M6 motorway between Liverpool and Manchester – as part of the new Leigh Sports Village for sports education, leading training programs, corporate activities and conferencing. -

Painting and Politics in the Vatican Museum Jan Matejko's

Jan Sobieski at Vienna (1683). A high quality color photograph of this painting and related works by Matejko can be found at https://www.academia.edu/42739074/Painting_and_Politics_April. Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies Vol. 60 (2019) Nos. 1–4, pp. 101–129 Painting and Politics in the Vatican Museum Jan Matejko’s Sobieski at Vienna (1683) Thomas M. Prymak Amid the splendours of the Vatican Museum in Rome, amongst the lush and abundant canvases of Raphael and other great artists, hangs an exceptionally large painting depicting the defeat of the last great invasion of Europe by the Turks: the relief of the 1683 siege of Vienna by a coalition of Christian forces led by the king of Poland, John III, also known as Jan Sobieski.1 Sobieski was the last king of Poland to attempt to restore his country’s power and glory before the steady decline and final disappearance of that state in the late eighteenth century, and he is written into the early modern history of Europe as the man who symbolized the repulse of that power- ful Ottoman attempt to conquer Europe, or, as it was seen then, the last Muslim invasion of Christendom. Though afterwards, historians would dispute who truly deserved credit for this impressive Christian victory over the armies of Islam, with several historians, Austrian and others, giving primary credit to one or another of the Austrian commanders, there is no doubt that Sobieski stood at the head of the multinational relief force, 1 Jan Matejko, Jan Sobieski, King of Poland, Defeats the Turks at the Gates of Vienna, oil on linen (485x894 cm), Sobieski Room, Vatican Palaces. -

VIENNA Gets High Marks

city, transformed Why VIENNA gets high marks Dr. Eugen Antalovsky Jana Löw years city, transformed VIENNA 1 Why VIENNA gets high marks Dr. Eugen Antalovsky Jana Löw Why Vienna gets high marks © European Investment Bank, 2019. All rights reserved. All questions on rights and licensing should be addressed to [email protected] The findings, interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank. Get our e-newsletter at www.eib.org/sign-up pdf: QH-06-18-217-EN-N ISBN 978-92-861-3870-6 doi:10.2867/9448 eBook: QH-06-18-217-EN-E ISBN 978-92-861-3874-4 doi:10.2867/28061 4 city, transformed VIENNA Austria’s capital transformed from a peripheral, declining outpost of the Cold War to a city that consistently ranks top of global quality of life surveys. Here’s how Vienna turned a series of major economic and geopolitical challenges to its advantage. Introduction In the mid-1980s, when Vienna presented its first urban development plan, the city government expected the population to decline and foresaw serious challenges for its urban economy. However, geopolitical transformations prompted a fresh wave of immigration to Vienna, so the city needed to adapt fast and develop new initiatives. A new spirit of urban development emerged. Vienna’s remarkable migration-driven growth took place in three phases: • first, the population grew rapidly between 1989 and 1993 • then it grew again between 2000 and 2006 • and finally from 2010 until today the population has been growing steadily and swiftly, by on average around 22,000 people per year • This means an addition of nearly 350,000 inhabitants since 1989.