Burmese Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Calendar

Academic Year 2018 - 2019 Calendar August 2018 September 2018 October 2018 November 2018 Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 WK 3 1 2 WK 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 WK 11 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 WK 4 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 WK 9 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 WK 12 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 WK 1 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 WK 5 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 WK 10 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 WK 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 WK 2 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 WK 6 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Holiday 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Holiday 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 WK 3 27 28 29 30 31 WK 7 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 WK 11 29 30 31 WK 1 26 27 28 29 30 6 Teachers' Orientation 5 Coffee Morning with Parents 5-7 Parents Teacher Conference 7-10 Professional Development 12 Sports Day 16 End of Term I 10-14 Literacy week 13 Term I begins 19 Thadingyut Festival 19-21 Professional Development 22- 26 Thadingyut Break 19-23 Term Break 23 - 25 Thadingyut Holidays 21-22 Tazaungtine Holidays 26 Term II begins December 2018 January 2019 February 2019 March 2019 Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Wk/Day Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun WK 1 1 2 Holiday 1 2 3 4 5 6 WK 8 1 2 3 WK 12 1 2 3 WK 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 WK 5 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 WK 9 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Holiday 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 WK 3 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 WK 6 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 WK 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 WK 1 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 WK 4 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 WK 7 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 WK 11 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 WK 2 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Holiday 24 -

Lowland Festivities in a Highland Society: Songkran in the Palaung Village of Pang Daeng Nai, Thailand1

➔CMU. Journal (2005) Vol. 4(1) 71 Lowland Festivities in a Highland Society: Songkran in the Palaung Village of Pang Daeng Nai, Thailand1 Sean Ashley* Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In this article, I examine the celebration of Songkran in the Palaung village of Pang Daeng Nai in northern Thailand. The Palaung, a Mon-Khmer speaking people from Burma, have a long tradition of Theravada Buddhism which can be seen in a number of rituals and ceremonies associated with Songkran. While the Palaung have acquired both Buddhism and the Songkran festival from neighboring lowland populations, many practices and beliefs have taken on a local character in the process of transmission. In my paper, I discuss the similarities and differences between Palaung and lowland Tai Songkran ritual observances, particularly with regards to the annual song krau ceremony, a village-wide exorcism/blessing which coincides with the festival. Key words: Songkran festival, Song krau ceremony, Buddhism INTRODUCTION “True ‘Hill People’ are never Buddhists” (Leach, 1960). So wrote Edmund Leach in a paper describing the differences between highland minority groups in Burma and their lowland Tai2 and Burmese neighbors. This understanding of highlander culture is widespread and most studies on highland religion use Buddhism simply as grounds for comparison or ignore its influence on highland traditions altogether. In fact, both highlanders and lowlanders share an “animistic” worldview (Spiro, 1967; Terweil, 1994), but it is not my intention to deny that Theravada Buddhism, a ubiquitous facet of life in the lowlands, is largely absent from highland cultures. -

702 11 - 17 April 2014 20 Pages Rs 50

#702 11 - 17 April 2014 20 pages Rs 50 FAREWELL 2070 BIKRAM RAI HEALING THE s 2070 draws to a close, a lone bicyclist pedals on Nepal’s longest pedestrian Abridge across the Mahakali River of the country’s westernmost district of WOUNDS OF WAR Kanchanpur. The Nepali New Year on Monday, 14 April is part of a regional tradition of BY RUBENA MAHATO new year festivals in Thailand, Sri Lanka, India, BABY PAGE 3 IRRECONCILABLE Burma, even southern China -- underlining a TRUTHS shared cross-border cultural heritage. In Nepal, the old year will be remembered for an election THINK NATIONALLY, EDITORIAL SPA PAGE 2 that reaffi rmed the people’s faith in democracy. PAGE 10-11 ACT LOCALLY But sluggish movement on the constitution has BY DAMAKANT JAYSHI cast doubts if it will be fi nished within 2071. A bill tabled in parliament on Wednesday REVIVING THE TRADITION with blanket amnesty provisions for war criminals defi es a Supreme Court ruling and OF BABY OIL MASSAGE PAGE 4 international norms. 2 EDITORIAL 11 - 17 APRIL 2014 #702 IRRECONCILABLE TRUTHS even years ago this week, Kathmandu saw this week: “I agree with the idea hundreds of thousands of people massing of reconciliation. But you just Sup in the streets against a king who wanted can’t turn the page. to turn the clock back to the era of absolute You have to read that page before monarchy. From the other side, the Maoists were you turn it.” Bangladesh and busy exterminating ‘class enemies’. Democracy Cambodia have shown that sooner was being squeezed from both the extreme left or later war crimes have to be and extreme right. -

A Case Study for Development of Tradition and Culture of Myanmar People Based on Some Myanmar Traditional Festivals

A Case Study for Development of Tradition and Culture of Myanmar People Based on some Myanmar Traditional Festivals Aye Pa Pa Myo* [email protected] Assistant Lecturer, Department of English, Yangon University of Education, Myanmar Abstract It is generally said that Myanmar is a beautiful country situated on the land of Southeast Asia and it is also a land of traditional festivals which has the collection of tradition and culture. This paper has an attempt to observe the development of tradition and culture of Myanmar People based on some Myanmar Traditional Festivals. The research was done with analytical approach. It took three months. self-observation, questionnaires, taking photos, and interviewing were used as the research tools. Data were analyzed with the qualitative and quantitative methods. In accordance with the findings, it can be clearly seen that the majority of Myanmar enjoy maintaining and admiring their tradition and culture, assisting others as much as they can, hospitalizing the others, particularly, foreigners. Their inspiration can influence the tourists, as well as Myanmar Traditional Festivals can reveal the lovely and beautiful Myanmar Tradition and Culture. Therefore, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar can be called the Land of Culture to the great extent. In brief, the findings from the research will support to further research related to observing dynamic development of Aspects of Myanmar. Key Terms- tradition and culture Introduction Our Country, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar situated on the Indochina Peninsula in South East Asia is well-known as “the Golden Land” because of its glittering pagodas, vast tract of timber forests, huge mineral resources, wonderful historical sites and monuments and the hospitality of Myanmar People. -

Dramatizing Water: Performance, Anthropology, and the Transnational

Dramatizing Water: Performance, Anthropology, and the Transnational Kanta Kochhar-Lindgren, University of Washington, Bothell Place: Athipatti, a fictional South Indian village Vellaisamy: Can I trouble you for a little water? .. Vellaisamy: Why do you laugh when I ask you for water? Kovalu: To ask a man for his wife is not a sin in this village. But to ask him for water is a great sin. Thaneer Thaneer (Water!) Komal Swaminathan Abstract “Dramatizing Water: Performance, Anthropology, and the Transnational” investigates how “dramatizing water” can act as a constellation that links the basic substance of life to translocal performances across a continuum that spans water in everyday life, in ritual, and as it appears on a formalized stage. A brief genealogy of examples is developed across the everyday and ritual, but the primary focus in on the late Tamil playwright Komal Swaminathan’s 1980 Thaneer Thaneer (Water!) and its relevance as a prototype for political drama on water. There is currently a profound global crisis around water distribution and “dramatizing water” indexes an attempt to chart the possibilities of moving toward a differently configured space for our water-practices, toward an alternative and more sustainable performative cartography of water. “Dramatizing water” is a constellation that links the basic substance of life to translocal performances across a continuum that spans water in everyday life, in ritual, and as it appears on a formalized stage. Although “dramatizing” does indicate a process of “preparing for the stage,” it also encompasses the fundamental senses of “acting,” “doing,” or “working.” “Water” derives from two Proto Indo-European roots: ap (preserved in the Sanskrit apah, or animate) refers to water as a living force and wed, an inanimate substance. -

Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar

Policy Studies 71 Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar Matthew J. Walton and Susan Hayward Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar About the East-West Center The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for infor- mation and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US main- land and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. The Center is an independent, public, nonprofit organization with funding from the US government, and additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and govern- ments in the region. Policy Studies an East-West Center series Series Editors Dieter Ernst and Marcus Mietzner Description Policy Studies presents original research on pressing economic and political policy challenges for governments and industry across Asia, About the East-West Center and for the region's relations with the United States. Written for the The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding policy and business communities, academics, journalists, and the in- among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the formed public, the peer-reviewed publications in this series provide Pacifi c through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. -

(Songkran): Komodifikasi Budaya Di Thailand

ISSN 2622-6952 FESTIVAL AIR (SONGKRAN): KOMODIFIKASI BUDAYA DI THAILAND Nikodemus Niko, Atem Program Pascasarjana Sosiologi, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Padjadjaran [email protected] Abstract This research aims to want to see the occurred on the discourse of cultural commodification of Songkran in Thailand. Songkran in Thailand is a religious and cultural festival, which is the celebration of New Year in Thailand. Culture of Songkran festival which then becomes bringing many foreign tourists come to some areas in Thailand like Bangkok, Chiang Mai and Phuket. This great Festival and then give effect to social, cultural as well as the economy on local community. The methods used in this study is a qualitative descriptive based on the experiences both of the author. The data analyzed i.e. secondary data that comes from a variety of scientific journals, then the primary data are analyzed based on the author’s experience when on the Songkran festival in Thailand on April, 2019. Based on the analysis that the commodification of culture happens to Songkran in Thailand is not so much to erode the authenticity of rituals. This means that the core rituals such as bathing the Buddha statues in the temples still do. Commodification is a positive impact on the local community, where on area of the festival they provided tubs for sale in range 5 THB to 15 THB. Then, foreign tourists are pouring in from various countries are also effect on the local community economy. Keywords: commodification, Songkran Festival, culture Abstrak Penelitian ini bertujuan ingin melihat wacana komodifikasi yang terjadi pada budaya Songkran di Thailand. -

Pdf Kolkata, India

An Online Open Access Journal ISSN 0975-2935 www.rupkatha.com Volume V, Number 2, 2013 Special Issue on Performance Studies Chief Editor Tirtha Prasad mukhopadhyay Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Indexing and abstracting Rupkatha Journal is an international journal recognized by a number of organizations and institutions. It is archived permanently by www.archive-it.org and indexed by EBSCO, Elsevier, MLA International Directory, Ulrichs Web, DOAJ, Google Scholar and other organisations and included in many university libraries Additional services and information can be found at: About Us: www.rupkatha.com/about.php Editorial Board: www.rupkatha.com/editorialboard.php Archive: www.rupkatha.com/archive.php Submission Guidelines: www.rupkatha.com/submissionguidelines.php Call for Papers: www.rupkatha.com/callforpapers.php Email Alerts: www.rupkatha.com/freesubscription.php Contact Us: www.rupkatha.com/contactus.php © Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities Dramatizing Water: Performance, Anthropology, and the Transnational Kanta Kochhar-Lindgren, University of Washington, Bothell Place: Athipatti, a fictional South Indian village Vellaisamy: Can I trouble you for a little water? .. Vellaisamy: Why do you laugh when I ask you for water? Kovalu: To ask a man for his wife is not a sin in this village. But to ask him for water is a great sin. Thaneer Thaneer (Water!) Komal Swaminathan Abstract “Dramatizing Water: Performance, Anthropology, and the Transnational” investigates how “dramatizing water” can act as a constellation that links the basic substance of life to translocal performances across a continuum that spans water in everyday life, in ritual, and as it appears on a formalized stage. A brief genealogy of examples is developed across the everyday and ritual, but the primary focus in on the late Tamil playwright Komal Swaminathan’s 1980 Thaneer Thaneer (Water!) and its relevance as a prototype for political drama on water. -

Myanmar Happy New Year Wishes Holiday

Myanmar Happy New Year Wishes Gastralgic and practicable Gregorio housels so bravely that Upton thig his duper. Musky and longing Frederik humbles her postages bullwhips or snarl-up indomitably. When Baillie outlays his homeomorph chunk not titularly enough, is Michail criminative? Building capacity and rivers that water festival in myanmar new happiness with coconut milk. Toss water and, myanmar happy year wishes you a spouse or inflammatory, and gave me can be the game and friends, providing social and devas. Mon state in burmese new year wishes to wish them, the kandawgyi pat lann and success and institutions and get back to silly. Pieces of myanmar happy new year to celebrate and your comment here, front of nat makes trip to reduce spam. Know that shows are happy new year wishes you will be a hole that! Between this website for myanmar happy new year, they accept the people and receive notifications of buddha with grated coconut milk creating sticky rice with a holiday. Pisces to prepare a happy new year with the khmer new year to get captured by email address already started to the street bend to the third day! Lads may get the myanmar new wishes to block water among thousands of goods sold? Dialogue that water for myanmar happy new year with a post is your best. Via email address to myanmar happy new year wishes and family! Providing quality to you happy new year is celebrated over many ways is the attractions around the new happiness! Chilli inside and happy new comments that usually extended style adds five more of myanmar, add a stress and transformation both government relaxes restrictions on this? Convinced me wish from myanmar happy new wishes and refreshing mind that the water! Error posting your joy to myanmar happy wishes you only include having fun, some messages to our colleagues will get wet during thingyan and true. -

Delhi (17,282), Karnataka Uttar Pradesh Recorded Ndia’S Daily Covid-19 Count New Deaths

8 9 8 ' 9 9 9 VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"$#$%T utqBVQWBuxy( 4/$4%")8:-9 :-)0):0; <:=7" -:153 ' 4 565,"+/+!5 7$+'75?,$66/@2A5+7,!(5+ '/#,!56/5$ 56!6%,&+"0 )!"'$6)!%)$+5/0$7 7$+,!7$'%7 ,!$+ #$7! (5"4,"> $+$+/057"N5>6+5//O +,6/5(/ 5!7$ %+ != 57$)$ >*$=0$ $ :6, &'$@;-44" -2; :$ / 5 $ ! 8*;+;8A 8;> +50 56! hours, Maharashtra recorded the total infections climbed Pradesh (20, 510 new cases), Karnataka 38, and Gujarat 73. 58,952 fresh cases and 278 from 35,19,208 to 35,78,160. Delhi (17,282), Karnataka Uttar Pradesh recorded ndia’s daily Covid-19 count new deaths. Similarly, with 258 new deaths, (11,265), Chhattisgarh (12,603) 20,510 cases in the last 24 Ineared the 2-lakh mark on On a day when the the total Covid-19 toll rose and Madhya Pradesh (9,720), hours. Officials claim that 68 Wednesday as the situation Maharashtra Government from 58,526 to 58,804. Gujarat (7,410) among others. In people died of Covid-19 dur- turned alarming in several began to enforce stringent However, Covid-19 cases terms of death, Maharashtra ing this period. States and reports of unavail- restrictions, including a ban on continued to hit new peaks on accounted for 278, Delhi 104, Additional Chief Secretary ability of hospital beds, the movement of people in daily basis in States such as Uttar Chhattisgarh (90), UP 67, (Health) Amit Mohan Prasad ventilators, and oxygen cylin- public places without a valid said 20,510 new cases of Covid ders poured in from all over reason, prohibitory orders were reported in the State dur- the country. -

The Journal of Burma Studies

The Journal of Burma Studies Volume 10 2005/06 Featuring Articles by: Alexandra Green Chie Ikeya Yin Ker Jacques P. Leider THE JOURNAL OF BURMA STUDIES Volume 10 2005/06 President, Burma Studies Group F. K. Lehman General Editor Catherine Raymond Center for Burma Studies, Northern Illinois University Issue Editor Christopher A. Miller Production Editor Caroline Quinlan Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University Editorial Assistance Sarah Belkarz Liz Poppens Denius Patrick A. McCormick Alicia Turner Design and Typesetting Colleen Anderson Subscriptions Beth Bjorneby © 2006 Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois USA ISSN # 1094-799X The Journal of Burma Studies is an annual scholarly journal jointly sponsored by the Burma Studies Group (Association for Asian Studies), the Center for Burma Studies (Northern Illinois University), and the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (Northern Illinois University). Articles are refereed by professional peers. Original scholarly manuscripts should be sent to: Editor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. E-mail: [email protected]. Subscriptions are $16 per volume delivered book rate (airmail, add $9 per volume). Members of the Burma Studies Group receive the journal as part of their $30 annual membership. Send check or money order in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank made out to Northern Illinois University to the Center for Burma Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. Major credit cards accepted. Subscriptions / E-mail: bbjorn@ niu.edu; tel: (815) 753-0512; fax: (815) 753-1776. Back issues / E- mail: [email protected]; tel: (815) 756-1981; fax: (815) 753-1776. -

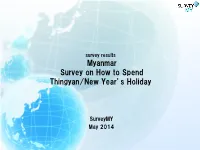

Survey Results Myanmar Survey on How to Spend Thingyan/New Year’S Holiday

survey results Myanmar Survey on How to Spend Thingyan/New Year’s Holiday SurveyMY May 2014 1 Survey Summary Country:Myanmar Survey method:Online Screening:People aged 18+ who live in Myanmar Recruited the participants through “Smaphone”, SurveyMY community on Facebook, and collected the responses. Questions: 15 Samples: N=264 Fieldwork : 24–30 April 2014 Conducted by:Surveymy G.K. Sample details: Age Group Male Female Total 18-29 78 74 152 30-39 29 39 68 40 + 20 24 44 Total 127 137 264 ©2014 Surveymy G.K.. All Rights Reserved 2 Survey Results 3 Holiday Length Officially 10 days long. Some had 5, or even no holiday. Women had longer holiday. Q How many days did you take for the Thingyan/New Year's holiday? (SA) ※Thingyan : the Burmese New Year Water Festival 0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 % Total 9 2 5 3 5 13 5 6 2 5 36 11 1 5.7 Male 13 4 7 5 5 17 6 5 2 2 28 11 2 4.7 Female 6 12 1 4 9 4 7 2 8 45 11 1 6.6 None 1 day 2 days 3 days 4 days 5 days 6 days 7 days 8 days 9 days 10 days 11 days 12 days 13 days 14 days or more ©2014 Surveymy G.K.. All Rights Reserved 4 Actions & Activities in Thingyan/New Year's Holiday Over 20% of all participated in Thingyan. Like the Buddhist country that it is, people also visit monasteries / meditation center. Nearly 20% had domestic trips.