Brownfamilyport00shearich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joshua Groban NEWEST ASSOCIATE JUSTICE of the SUPREME COURT of CALIFORNIA

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · spring/summer 2019 Joshua Groban NEWEST ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA On Page 2: Insights from a Former Colleague By Justice Gabriel Sanchez The Supreme Court of California: Associate Justices Leondra Kruger, Ming Chin, and Goodwin Liu, Chief Justice of California Tani Cantil-Sakauye, Associate Justices Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar, Carol Corrigan and Joshua Groban. Photos: Judicial Council of California Introducing Justice Joshua Groban by Justice Gabriel Sanchez* hen Joshua Paul Groban took the oath of A native of San Diego, Groban received his Bach- office as an associate justice of the California elor of Arts degree from Stanford University, major- WSupreme Court on January 3, 2019, he was in ing in modern thought and literature and graduating one sense a familiar face to attorneys and judges through- with honors and distinction. He earned his J.D. from out the state. As a senior advisor to Governor Edmund G. Harvard Law School where he graduated cum laude Brown Jr., Justice Groban screened and interviewed more and then clerked for the Honorable William C. Con- than a thousand candidates for judicial office. Over an ner in the Southern District of New York. He was an eight-year span, the governor, with Groban’s assistance accomplished litigator at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Whar- and advice, appointed 644 judges, including four of the ton & Garrison from 1999 to 2005 and Munger, Tolles seven current justices on the California Supreme Court & Olson in Los Angeles from 2005 to 2010, where he and 52 justices on the California Courts of Appeal. -

Governor Brown's Transportation Funding Plan

Governor Brown’s Transportation Funding Plan This proposal is a balance of new revenue and reasonable reforms to ensure efficiency, accountability and performance from each dollar invested to improve California’s transportation system. Governor Brown’s Transportation Funding Plan Frequently Asked Questions This proposal is a combination of new revenue and reform with measurable targets for improvements including regular reporting, streamlined projects with exemptions for infrastructure repairs and flexibility on hiring for new workload. How much does this program provide overall for transportation improvements? • Over the next decade, the Governor’s Transportation Funding Plan provides an estimated $36 billion in funding for transportation, with an emphasis on repairing and maintaining existing transportation infrastructure and a commitment to repay an additional $879 million in outstanding loans. How much does it require the average vehicle owner in California to pay? • The proposal equates to roughly 25-cents per motorist per day according to the Department of Finance. The latest TRIP* study released, and subsequent article in the Washington Post, showed that Californians spend on average $762 annually on vehicle repair costs due to wear and tear / road conditions, etc. http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonkblog/ wp/2015/06/25/why-driving-on-americas-roads-can-be-more-expensive-than-you-think/ A figure that should go down significantly with improved road conditions. How will the program improve transportation in California over the next decade? • Within 10 years, with this plan, the state has made a commitment to get our roadways up to 90% good condition. Today, 41% of our pavement is either distressed or needs preventative maintenance. -

President - Telephone Calls (2)” of the Richard B

The original documents are located in Box 17, folder “President - Telephone Calls (2)” of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 17 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ,;.._.. ~~;·.~·- .·.· ~-.. .· ..·. ~- . •.-:..:,.:·-. .-~-:-} ·· ~·--· :·~·-.... ~.-.: -~ ·":~· :~.·:::--!{;.~·~ ._,::,.~~~:::·~=~:~;.;;:.;~.;~i8JitA~w~;ri~r·•v:&;·~ ·e--.:.:,;,·.~ .. ~;...:,.~~,·-;;;:,:_ ..• THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON K~ t.l T ..u:. \(. y l\,~~;'"Y # 3 < . ~OTt.~ ~~~ -"P1ltS.tDI!'-'l' ~t&.. c. -y"Ro"&At.&.y vasir Ke'-',.uc..~ty .. ,... -f.le.. tL>e.e..te.NI) 0 ~ Mf'\y l'i, IS. Th\.s will he ~t.\ oF' ~ 3 ' . $ T _,.-c... &~• u~ +~ \\.)t.lvct t. Te~t.>~s••• ,..,.~ fh:.""'''". ORIGINAL . •· . SPECIAL Do RETIRED· TO . · CUMENTS Ftf. .E . ~- .~ ·. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON RECOMMENDED TELEPHONE CALL TO Congressman Tim Lee Carter {Kentucky, 5th District) 225-4601 DATE Prior to May 25 primary in Kentucky RECOMMENDED BY Rog Morton, Stu Spencer PURPOSE To thank the Congressman for his April 5th endorsement and for the assistance of his organization. -

Maine Campus February 01 1980 Maine Campus Staff

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Campus Archives University of Maine Publications Spring 2-1-1980 Maine Campus February 01 1980 Maine Campus Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus Repository Citation Staff, Maine Campus, "Maine Campus February 01 1980" (1980). Maine Campus Archives. 1046. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus/1046 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Campus Archives by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. the daily The University of/Maine at Orono aine student newspaper am since 1875 vol 86, no,10 Friday, Feb. 1,1980 Brown talks on country's needs by Stephen Betts On the subject of Iran, Brown conceded Staff writer the United States "shouldn't yield to blackmail" but he questioned Carter's handling of the hostage situation. Brown Presidential hopeful Ciovernor Jerry said he felt a physical blockade of Iran Brown told an overflow audience at would push that country closer to the Hauck Auditorium Thursday afternoon the Soviet Union. United States must shift its emphasis from The governor criticized Carter on his one of consumption to one of conservation. decision to allow the Shah of Iran into the Brown, speaking before a crown estimat- nation for medical treatment. "The ed at 800, spoke to the students for nearly president received a warning on the an hour on the need for America "to live embassy cable saying the shah's entrance within our means.'and not "continue to go into this country might prompt an attack on down a road that is stealing from the rest of the embassy, but he decided not to heed the world. -

William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, and HUMAN RIGHTS

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, AND HUMAN RIGHTS Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2008-2009 Copyright © 2009 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and William Newsom, dated August 7, 2009, and Barbara Newsom, dated September 22, 2009 (by her executor), and Brennan Newsom, dated November 12, 2009. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Lassiter JUH Submission Jan2015

Note to Lunch U.P. group: This is the draft submission of an article that will be coming out later this year in a special issue of the Journal of Urban History on “Rethinking Urban Spaces in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” edited by Heather Thompson and Donna Murch. It’s excerpted from a longer chapter, about ‘juvenile delinquency’ and the federal and state declarations of war on narcotics during the 1950s, from my book project The Suburban Crisis: Crime, Drugs, and the Lost Innocence of Middle-Class America. Thanks in advance for reading this before the discussion. I realize this is fairly different from most of the other aspects of the programming this semester and through a mix-up I didn’t realize until just now that I was on the calendar, so don’t have time to put together a formal presentation. But I will bring the map and images I plan to include with this article, which is not yet in the copyediting phase. Also, please don’t circulate this draft beyond the listserv for this workshop series. Thanks, Matt Lassiter [email protected] Pushers, Victims, and the Lost Innocence of White Suburbia: California’s War on Narcotics during the 1950s Matthew D. Lassiter University of Michigan During the 1950s, neighborhood groups and civic organizations representing more than one million residents of California petitioned the state government for lengthy mandatory- minimum sentences for dope “pushers” who supplied marijuana and heroin to teenagers, with considerable public sentiment for life imprisonment or the death penalty. California’s war on narcotics enlisted a broad and ideologically diverse spectrum, led by nonpartisan alliances such as the California Federation of Women’s Clubs and the statewide PTA network and advanced by Republican and Democratic policymakers alike. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

September 11, 2017 VIA EMAIL and PERSONAL DELIVERY the Honorable Tani G. Canti

September 11, 2017 VIA EMAIL AND PERSONAL DELIVERY The Honorable Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye, Chief Justice and Associate Justices SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA 350 McAllister Street Room 1295 San Francisco, California 94902-4797 RE: The California Bar Exam – Adjustment to the Minimum Passing Score Dear Chief Justice and Associate Justices: The undersigned Deans of the California Accredited Law Schools (CALS) request leave to file this Letter Brief to ask the Court to exercise its inherent power to admit persons to practice law in California and to adjust the minimum passing score (cut score) of the California bar exam.1 Following comprehensive study and analysis of minimum competence, the CALS join with many other stakeholders and experts, including the State Bar of California, in supporting a change in the minimum passing score of the California Bar Exam to 1390, as the one score that represents the intersection of research data, norms, current practice, and policy. The CALS previously petitioned the Court on March 2, 2017 to request an adjustment to the minimum passing score from 1440 to 1350.2 In response, the Court expressed its concern that it “lacks a fully developed analysis with supporting evidence from which to conclude that 1440 or another cut score would be most appropriate for admission to the bar in California.”3 The Court directed the State Bar of California (State Bar) to conduct “a thorough and expedited investigation” that includes “a meaningful analysis of the current pass rate and information sufficient to determine whether protection of potential clients and the public is served by maintaining the current cut score.”4 1 California Rules of Court, Rules 9.3(a) and 9.6(a), as amended and effective on January 1, 2018. -

Appendix I: Photographs

California State Archives Jesse M. Unruh Papers Page 45 Appendix I: Photographs The following headings are in Audiovisual Materials – Photographs: Jesse M. Unruh Portraits, circa 1960-1969 (1ff) LP236:1676 (1-30) Jesse with Elected Officials: includes Lyndon Johnson, George McGovern, LP236:1677 Pat Brown, Hubert Humphrey, Alan Cranston, Hugh Burns, Richard Nixon, (1-37) and others, circa 1963-1972 (1ff) Good Government Program, 1964 (1ff) LP236:1678 (1-8) President Harry Truman, 1965 (1ff) LP236:1679(1) Democratic LCC: Democratic legislators posed with Governor Pat Brown, LP236:1680 Unruh or alone, circa 1964-1966 (2ff) (1-41), LP236:1681 (1-57) Wide World Photos: Unruh activities as Speaker, 1966-1969 (1ff) LP236:1682 (1-22) Bay Area Events: includes March Fong, Byron Rumford, Dianne Feinstein, LP236:1683 1967 (1ff) (1-13) Kennedy Dinner, 1967 (1ff) LP236:1684 (1-33) Robert F. Kennedy: portraits, 1967-1968 (1ff) LP236:1685 (1-2) Robert F. Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel, 1968 (1ff) LP236:1686 (1-4) Unruh Press Conference, 1968 (1ff) LP236:1687 (1-12) Joint Press Conferences, 1968-1969 (1ff) LP236:1688 (1-8) McGovern Campaign Event, circa 1968 (1ff) LP236:1689 (1-14) Unruh at Chicago Convention, 1968 (1ff) LP236:1690 (1-7) Unruh Birthday Party, 1969 (1ff) LP236:1691 (1-13) Jess with Ralph Nader, 1969 (1ff) LP236:1692 (1-4) Unruh with Congressmen, National Press Club, 1969 (1ff) LP236:1693 (1-3) San Francisco Fundraising Event, 1970 (1ff) LP236:1694 (1-15) Muskie Reception, 1968 (1ff) LP236:1695 (1-18) California State Archives Jesse M. -

Elizabeth Snyder Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt438nf0xb No online items Inventory of the Elizabeth Snyder Papers Processed by David O'Brien California State Archives 1020 "O" Street Sacramento, California 95814 Phone: (916) 653-2246 Fax: (916) 653-7363 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/ © 2009 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Elizabeth Snyder C138 1 Papers Inventory of the Elizabeth Snyder Papers Collection number: C138 California State Archives Office of the Secretary of State Sacramento, California Processed by: David O'Brien Date Completed: December 2008 Encoded by: Sara Kuzak © 2009 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Elizabeth Snyder Papers Dates: 1937-1987 Collection number: C138 Creator: Elizabeth Snyder Collection Size: 3 cubic feet Repository: California State Archives Sacramento, California Abstract: The Elizabeth Snyder Papers consist of 2 cubic feet of records covering the years 1937 to 1987, with the bulk of materials covering 1953 to 1956, when she was Chair of the Democratic State Central Committee (DSCC), and 1977 to 1987, when she was active in the feminist movement in the Southern California region. Physical location: California State Archives Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights For permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the California State Archives. Permission for reproduction or publication is given on behalf of the California State Archives as the owner of the physical items. The researcher assumes all responsibility for possible infringement which may arise from reproduction or publication of materials from the California State Archives collections. -

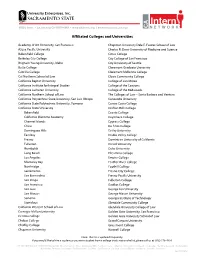

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

2010-2011 Course Listings

A n n u a l R e p o r t 2 0 1 UCLA 0 Institute - for Research 2 0 on Labor and 1 Employment 1 Table of Contents Letter from the Director.....................................................................................................................1 About IRLE.........................................................................................................................................2 History................................................................................................................................................3 Governance.........................................................................................................................................5 Governance Structure.......................................................................................................6 IRLE Leadership................................................................................................................8 Department Organization Chart.....................................................................................9 Staff Awards .......................................................................................................................10 Financial Issues .................................................................................................................11 Extramural Support..........................................................................................................12 Academic Activities...........................................................................................................................13