September 11, 2017 VIA EMAIL and PERSONAL DELIVERY the Honorable Tani G. Canti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* Fewer Than 11 Applicants Attorneys Admitted in Other Jurisdictions Less

GENERAL STATISTICS REPORT JULY 2018 CALIFORNIA BAR EXAMINATION OVERALL STATISTICS FOR CATEGORIES WITH MORE THAN 11 APPLICANTS WHO COMPLETED THE EXAMINATION First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Applicant Group Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass General Bar Examination 5132 2816 54.9 2939 468 15.9 8071 3284 40.7 Attorneys’ Examination 297 121 40.7 225 48 21.3 522 169 32.4 Total 5429 2937 54.1 3164 516 16.3 8593 3453 40.2 DISCIPLINED ATTORNEYS EXAMINATION STATISTICS Took Pass %Pass CA Disciplined Attorneys 19 1 5.3 GENERAL BAR EXAMINATION STATISTICS First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Law School Type Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass CA ABA Approved 3099 1978 63.8 1049 235 22.4 4148 2213 53.4 Out-of-State ABA 924 538 58.2 417 52 12.5 1341 590 44.0 CA Accredited 233 38 16.3 544 51 9.4 777 89 11.5 CA Unaccredited 66 10 15.2 259 22 8.5 325 32 9.8 Law Office/Judges’ Chambers * * * Foreign Educated/JD Equivalent 149 28 18.8 171 24 14.0 320 52 16.3 + One Year US Education US Attorneys Taking the 295 172 58.3 130 44 33.8 425 216 50.8 General Bar Exam1 Foreign Attorneys Taking the 352 46 13.1 309 38 12.3 661 84 12.7 General Bar Exam2 3 4-Year Qualification * 30 0 0.0 36 1 2.8 Schools No Longer in Operation * 26 1 3.8 32 4 12.5 * Fewer than 11 Applicants 1 Attorneys admitted in other jurisdictions less than four years must take and those admitted four or more years may elect to take the General Bar Examination. -

University of Oregon School of Law 2,315,690 Brigham Young

Rank Law School Score 1 University of Oregon School of Law 2,315,690 2 Brigham Young University School of Law 1,779,018 3 University of Illinois College of Law 1,333,703 4 DePaul University College of Law 976,055 5 University of Utah College of Law 842,671 6 Suffolk University Law School 700,616 St. Mary's University of San Antonio School 564,703 7 of Law 8 Northern Illinois University College of Law 537,518 9 University of Michigan Law School 500,086 10 College of William & Mary 431,510 LexisNexis Think Like A Lawyer Case Law Game Exampionship Leaderboard NOTE: Rankings are based on the cumulative Think Like A Lawyer Game scores for each school, which is a combination of the top scores of all students from each school. Page 1 of 5 11 Charlotte School of Law 404,331 12 University of Nevada Las Vegas - William S. Boyd School of Law 356,763 13 Lewis and Clark Law School 342,146 14 Gonzaga University School of Law 300,753 15 University of Houston Law Center 297,125 16 South Texas College of Law 293,509 17 University of South Carolina Law Center 284,762 18 Howard University School of Law 278,628 19 Michigan State University School of Law 266,731 20 Washington University School of Law 243,097 21 Willamette University College of Law 239,586 22 Texas Southern University 223,523 23 Tulane University Law School 200,823 24 Barry University School of Law 200,428 25 St. Thomas University School of Law 193,744 26 University of Miami School of Law 191,251 27 University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law 187,862 28 Northeastern University School -

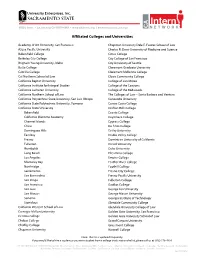

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

Student Handbook 2020-2021

Monterey College of Law San Luis Obispo College of Law Kern County College of Law Student Handbook 2020-2021 Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................................................. 3 Course Times/Locations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Accreditation ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Bar Pass Statistics ...................................................................................................................................... 4 COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA ................................................................ 4 Registration as a Law Student ................................................................................................................... 4 Equal Opportunity and Non-Discrimination ............................................................................................. 4 The First Year Law Students’ Examination (“FYLSX” or “Baby Bar”) ......................................................... 4 Admission to Practice Law in California .................................................................................................... 5 Practicing Law in Other States ................................................................................................................. -

Feb 2018 Cal Bar Exam

GENERAL STATISTICS REPORT FEBRUARY 2018 CALIFORNIA BAR EXAMINATION1 OVERALL STATISTICS FOR CATEGORIES WITH MORE THAN 11 APPLICANTS WHO COMPLETED THE EXAMINATION First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Applicant Group Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass General Bar Examination 1267 498 39.3 3434 784 22.8 4701 1282 27.3 Attorneys’ Examination 391 211 54.0 211 50 23.7 602 261 43.4 Total 1658 709 42.8 3645 834 22.9 5303 1543 29.1 DISCIPLINED ATTORNEYS EXAMINATION STATISTICS Took Pass % Pass CA Disciplined Attorneys 25 0 0 GENERAL BAR EXAMINATION STATISTICS First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Law School Type Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass CA ABA Approved 316 143 45.3 1423 445 31.3 1739 588 33.8 Out-of-State ABA 164 58 35.4 538 144 26.8 702 202 28.8 CA Accredited 122 28 23.0 570 52 9.1 692 80 11.6 CA Unaccredited 75 16 21.3 244 18 7.4 319 34 10.7 Law Office/Judges’ * * * Chambers Foreign Educated/JD 68 7 10.3 157 17 10.8 225 24 10.7 Equivalent + One Year US Education US Attorneys Taking the 310 204 65.8 140 64 45.7 450 268 59.6 General Bar Exam2 Foreign Attorneys 198 38 19.2 312 44 14.1 510 82 16.1 Taking the General Bar Exam3 4-Year Qualification4 * 19 0 0 26 0 0 Schools No Longer in * 29 0 0 33 1 3.0 Operation * Fewer than 11 Applicants 1 These statistics were compiled using data available as of the date results from the examination were released. -

General Statistics Report February 2015 California Bar Examination1 Overall Statistics

GENERAL STATISTICS REPORT FEBRUARY 2015 CALIFORNIA BAR EXAMINATION1 OVERALL STATISTICS First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Applicant Group Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass General Bar Examination 1524 723 47.4 3237 1159 35.8 4761 1882 39.5 Attorneys’ Examination 281 159 56.6 188 57 30.3 469 216 46.1 Total 1805 882 48.9 3425 1216 35.5 5230 2098 40.1 DISCIPLINED ATTORNEYS EXAMINATION STATISTICS Took Pass % Pass CA Disciplined Attorneys 29 0 0.0 GENERAL BAR EXAMINATION STATISTICS First-Timers Repeaters All Takers Law School Type Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass Took Pass %Pass CA ABA Approved 440 237 53.9 1403 666 47.5 1843 903 49.0 Out-of-State ABA 232 94 40.5 610 232 38.0 842 326 38.7 CA Accredited 132 40 30.3 491 85 17.3 623 125 20.1 CA Unaccredited 93 33 35.4 206 31 15.0 299 64 21.4 Law Office/Judges’ 0 0 0.0 2 1 50.0 2 1 50.0 Chambers Foreign Educated/JD 52 11 21.2 101 21 20.8 153 32 20.9 Equivalent + One Year US Education US Attorneys Taking the 388 268 69.1 168 73 43.5 556 341 61.3 General Bar Exam2 Foreign Attorneys 181 39 21.5 204 49 24.0 385 88 22.9 Taking the General Bar Exam3 4-Year Qualification4 6 1 16.7 13 1 7.7 19 2 10.5 Schools No Longer in 0 0 0.0 39 0 0.0 39 0 0.0 Operation Total 1524 723 47.4 3237 1159 35.8 4761 1882 39.5 1 These statistics were compiled using data available as of the date results from the examination were released. -

11.1. Chief Judge Thelton E. Henderson, U.S. District Court, Chief Judge Peckham Passed

Section 11 Letters to President Clinton from,,. People involved in Larry's trials 11.1. Chief Judge Thelton E. Henderson, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California - Colleague of Chief Judge Peckham Chief Judge Peckham passed away in 1993. We asked his successor, Chief Judge Henderson, to write a letter endorsing Judge Peckham's credentials and judgment. 11.2. Chief Probation Officer Loren Buddress, Northern District of California Besides Chief Judge Peckham, Mr. Buddress is the most knowledgeable individual of the facts of this case. He spent hours with Chief Judge Peckham discussing the complexities, minutiae, and ramifications of the case and knows first-hand Judge Peckham's feelings about the case. 11.3. Frank Bell- Larry's attorney in the first trial and for his parole application 11.4. Lois Franco- Criminal Justice Consultant who worked on Larry's behalf 11.5. Dr. Philip Zimbardo- Professor of Psychology, Stanford University 11.6. Sally Dwyer- Widow of Deputy Chief of Mission Richard Dwyer 11.7. Marshall Bentzman, Esq., Charles Garry's office 11.8. Pat Richartz, Private Investigator, Charles Garry's office United States District Court NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO. CALIFORNIA 94102 THELTON E. HENDERSON CHIEF JUDGE May 16, 1997 Honorable William Jefferson Clinton President of the United States The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Washington, D. C 20500 Re: Lawrence John Lavton: Petition for Commutation Dear Mr. President: I am writing to you regarding the Petition for Commutation, filed on behalf of Lawrence John Layton. For your convenient reference, I am attaching a copy of the Petition. -

Annual Giving Report 2014 Baylegal Ensures Fairness for the Unrepresented in the Civil Justice System

Annual Giving Report 2014 BayLegal ensures fairness for the unrepresented in the civil justice system. We help our clients protect their livelihoods, their health, and their families. BayLegal makes it easier to access legal information, assistance, and representation—so people can protect their rights and change their lives. BayLegal is the only legal aid organization serving the entire Bay Area—seven counties, seventy-five attorneys and advocates, one mission: use the power of law to build a better Bay Area. Investing in civil legal aid has been recognized as effective, results-oriented philanthropy. In addition to improving the lives of thousands of individuals each year, BayLegal’s attorneys solve systemic problems to protect vulnerable people and save tax dollars. This work could not happen without the generosity and commitment of the financial and pro bono contributors recognized in this Annual Giving Report. We are grateful for your partnership as we work together to make a real and lasting change in our communities. Thank you! 2014 AnnualDonorReception Many thanks to our hosts, Keker & Van Nest Many thankstoourhosts,Keker&Van 2014 Donor List LAW FIRMS Wilmer Hale LLP Wolf Fenella & Stevens LLP Platinum $55,000+ Law Offices of Andrew Wolff Cooley LLP Kazan McClain Abrams, Fernandez, Cy Pres Lyons, Greenwood, Oberman Law Offices of Aram Antaramian Satterley & Bosl Foundation Bernstein, Litowitz, Berger & The Morrison & Foerster Foundation Grossman, LLP Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Chavez & Gertler LLP Rosati Foundation Kemnitzer Barron -

Understanding the U.S. News Law School Rankings

SMU Law Review Volume 60 Issue 2 Article 6 2007 Understanding the U.S. News Law School Rankings Theodore P. Seto Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Theodore P. Seto, Understanding the U.S. News Law School Rankings, 60 SMU L. REV. 493 (2007) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol60/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. UNDERSTANDING THE U.S. NEws LAW SCHOOL RANKINGS Theodore P. Seto* UCH has been written on whether law schools can or should be ranked and on the U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT ("U.S. NEWS") rankings in particular.' Indeed, in 1997, one hundred *Professor, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. The author is very grateful for the comments, too numerous to mention, given in response to his SSRN postings. He wants to give particular thanks to his wife, Professor Sande Buhai, for her patience in bearing with the unique agonies of numerical analysis. 1. See, e.g., Michael Ariens, Law School Brandingand the Future of Legal Education, 34 ST. MARY'S L. J. 301 (2003); Arthur Austin, The Postmodern Buzz in Law School Rank- ings, 27 VT. L. REv. 49 (2002); Scott Baker et al., The Rat Race as an Information-Forcing Device, 81 IND. L. J. 53 (2006); Mitchell Berger, Why the U.S. News & World Report Law School Rankings Are Both Useful and Important, 51 J. -

100 Campus Center, Building 86E CSU Monterey

THE NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF ADVISORS The Honorable Ms. Andrea Mitchell Nancy Kassebaum Baker Dr. Barry Munitz The Honorable Cruz Bustamante The Honorable Robert Putnam Mr. Lewis H. Butler The Honorable Bill Richardson Mr. Stephen Caldeira Ms. Cokie Roberts The Honorable Henry Cisneros Mr. Bob Schieffer The Honorable Ron Dellums The Honorable Donna Shalala Mr. Clint Eastwood The Honorable Alan Simpson Dr. David P. Gardner Dr. Peter Smith Mr. Richard A. Grasso The Honorable Dr. Philip R. Lee Clifton R. Wharton, Jr. The Honorable John Lewis Dr. Timothy P. White Ms. Laura A. Liswood Ms. Rhonda A. Williams ACADEMIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE George Blumenthal, Ph.D., Chancellor University of California, Santa Cruz Bradley Davis, J.D., President, West Valley College Col. Phillip J. Deppert, USA, Commandant Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center James Donahue, Ph.D., President, Saint Mary’s College of California Fr. Michael E. Engh, S.J., President, Santa Clara University Laurel Jones, Ph.D., Superintendent/President, Cabrillo College Kathleen Rose, Ed.D. Superintendent/President, Gavilan College Nancy Kotowski, Ph.D., Monterey County Superintendent of Schools THETHE PANETTA PANETTA INSTITUTE INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY Willard Clark Lewallen, Ph.D., Superintendent/President, Hartnell College 100FOR Campus PUBLIC PCenter,OLICY Building 86E Mary B. Marcy, Ph.D., President, Dominican University of California CSU100 Monterey Campus Center Bay, / Building Seaside, 86E California 93955 Eduardo M. Ochoa, Ph.D., President, California State University, Monterey Bay CSU MontereyTel: 831-582-4200 Bay / Seaside, California Fax: 831-582-4082 93955 Jeff Dayton-Johnson, Ph.D., Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean Tel: [email protected] / Fax: 831-582-4082 Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey [email protected] www.panettainstitute.org Vice Admiral Ronald Route, USN (Ret.), President, Naval Postgraduate School Walter Tribley, Ph.D., Superintendent/President, Monterey Peninsula College Mitchel L. -

Golden Gate Lawyer, Summer 2012 Lisa Lomba Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected]

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Golden Gate Lawyer Other Law School Publications Summer 2012 Golden Gate Lawyer, Summer 2012 Lisa Lomba Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulawyer Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lomba, Lisa, "Golden Gate Lawyer, Summer 2012" (2012). Golden Gate Lawyer. Paper 12. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulawyer/12 This Newsletter or Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Other Law School Publications at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Golden Gate Lawyer by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOLDEN GATE LAWYER THE MAGAZINE OF GOLDEN GATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Summer 2012 Women’s Rights Champion SARAH WEDDINGTON Counsel in Roe v. Wade Women’s Reunion Keynote Speaker 26940_GGU_lawyerAC.indd 1 6/29/12 11:57 AM What distinguishes GGU Law? Practice-Based Learning, Practice-Ready Graduates Decades before experiential learning gained pedagogical Some of GGU’s unique offerings include: traction, GGU Law professors were preparing students Honors Lawyering Program to be excellent practicing attorneys. We teach students Summer Trial and Evidence Program through skills-infused classes and community-based Law and Leadership Program clinical programs. Myriad opportunities in and beyond the classroom and GGU Law campus create practice- Joint JD/MBA Degree Program ready graduates with substantive community connections. Award-Winning On-Site Clinics Assisting Underserved Communities Today, GGU Law continues to enrich its emphasis on experiential learning—preparing tomorrow’s law leaders ■ Women’s Employment Rights Clinic for whatever paths they take. -

Hastings Community (Fall 1988) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association

UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Alumni Publications 9-1-1988 Hastings Community (Fall 1988) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag Recommended Citation Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association, "Hastings Community (Fall 1988)" (1988). Hastings Alumni Publications. 72. http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag/72 This is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Alumni Publications by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. FALL1988 University of California, Hastings College ofthe Law m Patino Fellowslin Increases to $7500.00 students have become Patino Fellows. selected as Tony Patino Fellows-elect. At this year's Selection Day Reception and Though the three Fellows-elect come from Luncheon held at the St. Francis Hotel in diverse backgrounds, they share the accom- San Francisco, three members of the plishment and character sought by the Hastings Class of 1988 were named Tony Fellowship. Patino Fellows, they are Mr. David Balter, "The Tony Patino Fellowship is a unique Ms. Shana Chung and Ms. Mary Jo Quinn. program. Its generous support of our Al three spoke of what the Fellowship has students is unmatched; its high and consis- meant to them and thanked Mrs. Turner for tently recognized ideals are compelling, her constant encouragement and generosity. said Dean Read. "The Fellowship identifies In addition, three incoming Hastings highly promising students at the beginning students -Melyssa D. Davidson, Leah Sue of their legal careers and gives them an Goldberg, and Stephen P.Van Liere -were enormous boost through the Fellowship's financial support.- Leah Sue Goldberg, one of this year's Fellows-elect, experienced some of the confusion many law students feel at Dean Read, 1988 Patino Fellows Mary Jo Quinn, David M.