William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, and HUMAN RIGHTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Equality

WOMEN AND EQUALITY A California Review of Women’s Equity Issues in Civil Rights, Education and the Workplace California Senate Office of Research February 1999 Dedicated to Senator Rose Ann Vuich Rose Ann Vuich was elected California’s first woman state senator in 1976 and served four terms through 1992. Although a Democrat by registration, she built a reputation as a political independent who shunned deal-making. Throughout her legislative career, Senator Vuich represented her San Joaquin Valley district first and foremost and relied on her own knowledge and judgment to do it. She was reared on a farm in Tulare County, where she has spent most of her life. With a degree in accounting from the Central California Commercial College in Fresno, she worked as an accountant, tax consultant, estate planner and office manager before her election. After becoming a senator she continued, with her brother, to manage the family farm in Dinuba. The California State Senate began to change after Senator Vuich joined its ranks, followed over the years by other women. She kept a small porcelain bell on her Senate floor desk, and would gently but insistently shake it whenever a colleague addressed the “gentlemen of the Senate.” The Senate chamber originally had no women’s restroom. But that oversight permitted Senator Vuich, during a Capitol restoration in the late 1970s, to design a comfortable “Rose Room” where she and women members into the future could retreat from the Senate floor. A daughter of Yugoslav immigrants, Senator Vuich achieved many “firsts,” from serving as the first woman president of the Dinuba Chamber of Commerce to becoming the first woman to preside over a Senate floor session in 1986. -

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk

“Destroy Every Closet Door” -Harvey Milk Riya Kalra Junior Division Individual Exhibit Student-composed words: 499 Process paper: 500 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Black, Jason E., and Charles E. Morris, compilers. An Archive of Hope: Harvey Milk's Speeches and Writings. University of California Press, 2013. This book is a compilation of Harvey Milk's speeches and interviews throughout his time in California. These interviews describe his views on the community and provide an idea as to what type of person he was. This book helped me because it gave me direct quotes from him and allowed me to clearly understand exactly what his perspective was on major issues. Board of Supervisors in January 8, 1978. City and County of San Francisco, sfbos.org/inauguration. Accessed 2 Jan. 2019. This image is of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the time Harvey Milk was a supervisor. This image shows the people who were on the board with him. This helped my project because it gave a visual of many of the key people in the story of Harvey Milk. Braley, Colin E. Sharice Davids at a Victory Party. NBC, 6 Nov. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/sharice-davids-lesbian-native-american-makes- political-history-kansas-n933211. Accessed 2 May 2019. This is an image of Sharcie Davids at a victory party after she was elected to congress in Kansas. This image helped me because ti provided a face to go with he quote that I used on my impact section of board. California State, Legislature, Senate. Proposition 6. -

From Hollywood, Anna Roosevelt Defends FDR's Performance at Yalta Which Had Recently Been Called in to Question by a Biased Reporter

THE ELEANOR AND ANNA ROOSEVELT PROGRAM November 17th, 1948 (air date) Description: From Hollywood, Anna Roosevelt defends FDR's performance at Yalta which had recently been called in to question by a biased reporter. From Paris, ER interviews Henry Morgenthau on Israel's refusal to relinquish hold on the Negev Desert. Participants: ER, Anna Roosevelt, John Nelson, Henry Morgenthau [John Nelson:] From Paris and Hollywood the American Broadcasting Company brings you Eleanor and Anna Roosevelt. [Anna Roosevelt:] Good morning and thank you, John Nelson. The news this morning as usual is full of conflict, contrast, and confusion with China and the Holy Land, the twin trouble spots of the day. And I noticed a new name has been added to the long list of Americans who've tried to work with the Chiang Kai-shek government in China and finally, in frustration and disillusionment, have thrown up their hands and concluded that it is impossible. The latest name is that of Roger Lapham, the former mayor of San Francisco and now head of China aid under the Marshall Plan. Lapham says he cannot accomplish anything with Chiang and threatens to bypass the generalissimo after this. There have been many others, General Stilwell for one, and for another, General Marshall, who returned from China greatly disillusioned. So I wonder what will be accomplished by William Bullitt, the former Ambassador to Russia who arrived in Shanghai the other day as a representative of the so-called Congressional Watchdog Committee on Foreign Aid. While Mr. Bullitt was crossing the Pacific I looked up his articles which appeared several weeks ago in Life magazine. -

Gavin Newsom Governor of California

GAVIN NEWSOM GOVERNOR OF CALIFORNIA Life in Brief Quick Summary Born: October 10, 1967 Progressive politician who has established a reputation of advocating for marginalized Hometown: San Francisco, CA groups such as racial minorities and the LGBT community through unorthodox means. Current Residence: Greenbrae, CA Effectively leveraged family connections to jumpstart career Religion: Catholic • Embraces forging his own path on progressive issues; publicly goes against the status quo Education: • Fights for what he believes is right through • BS, Political Science, Santa Clara University, unconventional means; as Mayor of San 1989 Francisco, broke the state law to support same- sex marriage, putting his reputation at risk with Family: the broader Democratic Party • Wife, Jennifer Siebel, documentary filmmaker • Shifted from the private sector to politics after and actress working for Willie Brown • Divorced, Kimberly Guilfoyle, political analyst • Working for Jerry Brown allowed him to learn and former Fox News commentator tools of the trade and become his successor • Four children • Well connected to CA political and philanthropic elites; Speaker Nancy Pelosi is his aunt and Work History: political mentor, and he is friends with Sen. • Governor of California, 2019-present Kamala Harris and the Getty family • Lt. Governor of California, 2011-2019 • Advocates for constituents to engage with their • Mayor of San Francisco, 2004-2011 government, using technology to participate • Member of the San Francisco Board of nd Supervisors from the -

Public Health and Criminal Justice Approaches to Homicide Research

The Relationship Between Non-Lethal and Lethal Violence Proceedings of the 2002 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group St. Louis, Missouri May 30 - June 2 Editors M. Dwayne Smith University of South Florida Paul H. Blackman National Rifle Association ii PREFACE In a number of ways, 2002 and 2003 represent transition years for the Homicide Research Working Group (HRWG), its annual meetings, variously referred to as symposia or workshops, and the Proceedings of those meetings. One major change, both in terms of the meetings and the Proceedings, deals with sponsorship. Traditionally, the HRWG’s annual meetings have been hosted by some institution, be it a university or group affiliated with a university, or a government agency devoted at least in part to the collection and/or analysis of data regarding homicides or other facets of homicide research. Prior to 2002, this generally meant at least two things: that the meetings would take place at the facilities of the hosting agency, and that attendees would be treated to something beyond ordinary panels related to the host agency. For example, in recent years, the FBI Academy provided an afternoon with tours of some of its facilities, Loyola University in Chicago arranged a field trip to the Medical Examiners’ office and a major hospital trauma center, and the University of Central Florida arranged a demonstration of forensic anthropology. More recently, however, the host has merely arranged for hotel facilities and meeting centers, and some of the panels, particularly the opening session. This has had the benefit of adding variety to the persons attracted to present at our symposia, but at the risk that they are unfamiliar with our traditional approach to preparing papers for the meetings and the Proceedings. -

108916NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • ., CAlKli:'()RNKA C()RTI~IECTKOl\JAt SYSTEM'S POlITCH1E§ RIE:C;ARTI)KNG PAROLE RJE1L1EASE • AND l\1E Nl'A ttY D rrS()R[) JERE D () IF flE NIJ£ RS ., • • • ! ~!, ' •. I' ) \ 1) .\,' '/ ) \' ' I 1\1. " ll'\'" l,:...; .• I) . ( ..L\ I!'.,.!. \ ' (,.~, ,I. ' I I j l , :: • " . I • I • • • • • • • a)'i ilirt! i kl,itj~j)ns ficp • ":tcl tL·1 CdP'll to ~ 9 h1m, 94 ?tv/. !) S~rr~rn~nto, tA Y4249-noo1 • • t.. • 108'Qlh CALIFORNIA CORRECTIONAL SYSTEM'S POLICIES REGARDING I PAROLE RELEASE I~ AND MENTALLY DISORDERED OFFENDERS • • • • ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC SAFETY • FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS I • LARRY STIRLING, Chair Robert Campbell Burt Margolin • Terry B. Friedman' Mike Roos Tim Lesl ie Paul E. Zeltner DeeDee D'Adamo 9 Counsel Laura Hankinss Consultant LARRY STIRLING CIIiEF COUNSEL CHAIR i\slltwbln SUSAN SHAW GOODMAN ROBERT CAMPBELL COUNSEL l'E~1RY B. FRIEDMAN LISA BURROUGHS WAGNER TIM LESLIE QtaUfnrnta 1JJegt111ature DEEDEE D'ADAMO BURr MARGOLIN MELISSA K NAPPAN MII<EROOS PAUL E ZELTNER CONSULTANT LAURA HANKINS COMMITTEE SECRETARY • DARLENE E. BLUE • 1100 ,) STREET SACRAMENTO. CA 95814 (916) 445,3268 • August 5~ 1987 Honorab 1e kJi 11 i e L. Brown 9 Jr. Speaker of the Assembly State Capitol~ Room 219 • Sacramento~ California 95814 Dear Mr. Speaker~ The attached documents represent the testimony presented to the Committee on Public Safety at the "Informational Hearing on Parole Release Policies and • Evaluations and Treatment of Mentally Disordered Offenders." Also included are the committee's findings and recommendations regarding these issues. -

Pacific Rim Report 39

Copyright 1988 -2005 USF Center for the Pacific Rim The Occasional Paper Series of the USF Center for the Pacific Rim :: www.pacificrim.usfca.edu Pacific Rim Report No. 39, June 2006 Beyond Gump’s: The Unfolding Asian Identity of San Francisco by Kevin Starr This issue of Pacific Rim Report records the Kiriyama Distinguished Lecture in celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the University of San Francisco delivered by Kevin Starr on October 24, 2005 on USF’s Lone Mountain campus. Kevin Starr was born in San Francisco in 1962, He served two years as lieutenant in a tank battalion in Germany. Upon release from the service, Starr entered Harvard University where he took his M.A. degree in 1965 and his Ph.D. in 1969 in American Literature. He also holds a Master of Library Science degree from UC Berkeley and has done post-doctoral work at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Starr has served as Allston Burr Senior Tutor in Eliot House at Harvard, executive assistant to the Mayor of San Francisco, the City Librarian of San Francisco, a daily columnist for the San Francisco Examiner, and a contributing editor to the Opinion section of the Los Angeles Times. The author of numerous newspaper and magazine articles, Starr has written and/or edited fourteen books, six of which are part of his America and the California Dream series. His writing has won him a Guggenheim Fellowship, membership in the Society of American Historians, and the Gold Medal of the Commonwealth Club of California. His most recent book is Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003 published by Alfred A. -

Mayor Angelo Rossi's Embrace of New Deal Style

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Trickle-down paternalism : Mayor Angelo Rossi's embrace of New Deal style Ronald R. Rossi San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Rossi, Ronald R., "Trickle-down paternalism : Mayor Angelo Rossi's embrace of New Deal style" (2009). Master's Theses. 3672. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.5e5x-9jbk https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3672 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRICKLE-DOWN PATERNALISM: MAYOR ANGELO ROSSI'S EMBRACE OF NEW DEAL STYLE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Ronald R. Rossi May 2009 UMI Number: 1470957 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 1470957 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. -

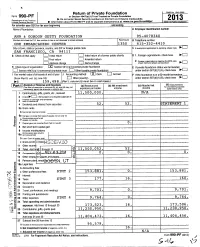

Return of Private Foundation

s III, OMB No 1545-0052 0, Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Treasury Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Department of the ► InterAal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.,rs.gov/form9!9Opf. en o u is ns ec ion For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginning and ending Name of foundation A Employer Identification number ANN & Gn RT)ON aRTTY FOUNDATION 95-4078340 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ONE EMBARCADERO CENTER 1350 415-352-441 0 City or town , state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94111 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ► O Address chan g e Name chan g e check here and attach computation H Check type of organization OX Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust = Other taxable p rivate foundati on under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► ^ I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part ll, col. -

July 18, 1972 Bill

24260 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 18, 1972 bill. Of course, any motion to recommit Mr. JAVITS. Mr. President, will the The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without the bill, if such were made, would be Senator yield? objection, it is so ordered. in order, there would be a time limita Mr. DOMINICK. I yield. Mr. ROBER'!' c. BYRD. I thank the tion on any such motion, under the re Mr. JAVITS. I should like to say to Chair. quest, of 30 minutes, and additional time the Senator from West Virginia that the ' could be yielded from the bill on any reason why we did what we did is that if PROGRAM motion or appeal. we have any amendment that we think Mr. DOMINICK. I thank the Senator. should go into the bill, which would affect Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, The PRESIDING OFFICER. Would the result of the voting on the substitute, the program for tomorrow is as follows : the Senator from West Virginia advise Senator WILLIAMS and I feel that if we The Senate will convene at 10 a.m. the Chair whether he has concluded his give adequate assurance to the Senate, After the two leaders have been recog unanimous-consent request? the Senate will take that into considera nized under the standing order, the dis Mr. ROBERT c. BYRD. Mr. President, tion in respect of its vote. tinguished senior Senator from Kentucky I ask unanimous consent that rule XII So I did not wish supporters of the bill (Mr. COOPER) will be recognized for not be waived in connection with the agree to feel that their rights have been prej to exceed 15 minutes, after which there ment for a vote on passage of the bill. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Oral History Interview with Milton Marks

CALIFORNIA SHU ~lCllnS California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with MILTON MARKS California State Assembly 1958-1966 California State Senate 1967-1996 January 23, 1996, January 24, 1996, January 25, 1996, February 27, 1996, February 28, 1996 Sacramento, California By Donald B. Seney California State Archives Volume Two SESSION 4, January 25, 1996 [Tape 6, Side A] 211 Winston Churchill--Travels--Interests in Environmental issues--Local Government Issues--BART--Working with Senator Moscone--More about BART -The question oflegislative pay--The mini-bus mobile office--The leadership battle in the Senate after 1970. [Tape 6, Side B] 230 The leadership battle in the Senate after 1970 election--Senator Randolph Collier -The Senate Rules Committee and Committee appointments--Changes in the Transportation Committee under James Mills--Other changes in Leadership- Schrade replaces Way--Mills replaces Schrade--George Deukmejian--Problems for Schrade--Gun Controllegislation--The Bay Conservation and Development Act--Farewell tribute when Senator Marks left Assembly--1970 Reapportionment -The 1972 Election. [Tape 7, Side A] 252 Senator Marks' relationship with Willie Brown--The 1972 Senate Campaign--The issues in the 1972 Campaign--A big victory in 1972--Mrs. Marks' Campaign for the Board of Supervisors--Mrs. Marks' contributions to Senator Marks' career- The perils oflisting address and phone number--The 1972 Election Generally- H.L. Richardson--Voting to override a Reagan veto. [Tape 7, Side B] 276 The Senator's Partisan Split after the 1972 election--The Indian Affairs Committee and the location ofthe Governor's Mansion--Legislation Sponsored by Senator Marks' from 1959 on--Open meeting legislation--Early environmental legislation--Financing Laws--Establishing the California Arts Commission- Legislation dealing with Treatment for alcoholism--Commission on the Status of Women--Other legislation--Legislation dealing with the disabled.