Berkshire's Disintermediation: Buffett's New Managerial Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uber Technologies Inc.: Managing Opportunities and Challenges

Center for Ethical Organizational Cultures Auburn University http://harbert.auburn.edu Uber Technologies Inc.: Managing Opportunities and Challenges INTRODUCTION Uber Technologies Inc. (Uber) is a tech startup that provides ride sharing services by facilitating a connection between independent contractors (drivers) and riders with the use of an app. Uber has expanded its operations to 58 countries around the world and is valued at around $41 billion. Because its services costs less than taking a traditional taxi, in the few years it has been in business Uber and similar ride sharing services have upended the taxi industry. The company has experienced resounding success and is looking toward expansion both internationally and within the United States. However, Uber’s rapid success is creating challenges in the form of legal and regulatory, social , and technical obstacles. The taxi industry, for instance, is arguing that Uber has an unfair advantage because it does not face the same licensing requirements as they do. Others accuse Uber of not vetting their drivers, creating potentially unsafe situations. An accusation of rape in India has brought this issue of safety to the forefront. Some major cities are banning ride sharing services like Uber because of these various concerns. Additionally, Uber has faced various lawsuits, including a lawsuit filed against them by its independent contractors. Its presence in the market has influenced lawmakers to draft new re gulations to govern this “app-driven” ride sharing system. Legislation can often hinder a company’s expansion opportunities because of the resources it must expend to comply with regulatory requirements. Uber has been highly praised for giving independent contractors an opportunity to earn money as long as they have a car while also offering convenient ways for consumers to get around at lower costs. -

Printmgr File

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. 3555 Farnam Street Omaha, Nebraska 68131 NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS May 1, 2021 TO THE SHAREHOLDERS: Notice is hereby given that the Annual Meeting of the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. will be held on May 1, 2021 at 5:00 p.m. Eastern time. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Annual Meeting will be held in a virtual format only to provide a safe experience for our shareholders and employees. Items of Business: 1. To elect directors. 2. To act on two shareholder proposals if properly presented at the meeting. 3. To consider and act upon any other matters that may properly come before the meeting or any adjournment thereof. The Board of Directors has fixed the close of business on March 3, 2021 as the record date for determining the shareholders having the right to vote at the meeting or any adjournment thereof. A list of such shareholders will be available for examination by a shareholder for any purpose germane to the meeting during ordinary business hours, during the ten days prior to the meeting. You are requested to date, sign and return the enclosed proxy which is solicited by the Board of Directors of the Corporation and will be voted as indicated in the accompanying proxy statement and proxy. A return envelope is provided which requires no postage if mailed in the United States. If mailed elsewhere, foreign postage must be affixed. At 1:30 p.m. Eastern time, a Question and Answer period will commence. The Question and Answer period will last until 5:00 p.m. -

2006 Annual Report

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. 2006 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Business Activities........................................................Inside Front Cover Corporate Performance vs. the S&P 500 ................................................ 2 Chairman’s Letter* ................................................................................. 3 Acquisition Criteria ................................................................................25 Report of Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm...................25 Consolidated Financial Statements.........................................................26 Selected Financial Data For The Past Five Years ..................................................................................53 Management’s Discussion ......................................................................54 Management’s Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting ...................................................................73 Owner’s Manual .....................................................................................74 Common Stock Data and Corporate Governance Matters......................79 Operating Companies .............................................................................80 Directors and Officers of the Company.........................Inside Back Cover *Copyright © 2007 By Warren E. Buffett All Rights Reserved Business Activities Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is a holding company owning subsidiaries that engage in a number of diverse business activities including property -

Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting May 5, 2012 These Notes Are Recollections Only, Without the Aid of a Recording Device

Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting May 5, 2012 These notes are recollections only, without the aid of a recording device. They should not be relied upon. –PB WB: Good morning. I’m Warren and this hyperkinetic fellow is Charlie. We’ll conduct this pretty much as we have in past. We’ll take questions until 3:30, and then begin the regular meeting of shareholders at that time. Feel free to shop. See ‘s Candy has placed a lollipop at every seat, and if you could open the lollipop now we’ll post a picture on Facebook, and for the media. And now you can take off the cover and good part comes. CM and I have fudge and peanut brittle. If we’ve consumed 10k calories each we’ll have to stop early. We released Q1 earnings yesterday. In general, all our companies with the exception of those in residential construction have pretty much shown good earnings. Our five largest non-reinsurance companies all had record earnings last year, $9bil pre-tax. I said that I thought they would earn $10bil pretax this year, and nothing we have seen so far would cause me to backtrack on this. One cost at Geico is an accounting change or deferred policy acquisition cost, dpac. No change on cash, but took earnings down 250m pretax. It is a deferred advertising issue. We had a terrific Q1 at Geico, float grew and we had a 9% margin. The Dpac charges may affect 2Q and a little in 3Q, but underlying figures are somewhat better than what we’ve presented. -

M60879 Annual Report 2002

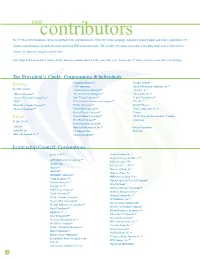

ourcontributors The FEI Research Foundation extends its gratitude to the contributors to its 2001-2002 annual campaign. Supporters included public and private corporations, FEI chapters and individuals from both the active and retired FEI membership ranks. We consider every donor our partner in providing timely, practical research to enhance the financial management profession. In the listings below, an asterisk (*) indicates that the donor has contributed for at least five consecutive years. Two asterisks (**) indicate at least ten consecutive years of giving. The President’s Circle: Corporations & Individuals Investor Corning Incorporated** Lockheed Martin** CVS Corporation Marsh & McLennan Companies, Inc.** $10,000 or more DaimlerChrysler Corporation** Medtronic, Inc.* Abbott Laboratories** The Dow Chemical Company** Merck & Co., Inc.** American International Group Inc.** Duke Energy Corporation** PepsiCo Incorporated** AT&T** E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company** Pfizer Inc.** Bristol-Myers Squibb Company** Eli Lilly & Company** David M. Taggart Microsoft Corporation** ExxonMobil Corporation** Tenneco Automotive Inc.** General Electric Company** Verizon Patron General Motors Corporation** Wyeth* (formerly American Home Products) H. J. Heinz Company** Anonymous $5,000- $9,999 Hewlett Packard Company** ALCOA** Household International, Inc.** In-kind Contributor Aquila Energy J.P. Morgan Chase Dell USA Baxter International, Inc.** Johnson & Johnson** Leadership Council: Corporations $2,000 - $4,999 Johnson Controls Inc.** Keyspan Energy -

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Brkb 084670702

Research Report Company Ticker Symbol CUSIP BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. BRKB 084670702 Guideline Meeting Date Record Date Date Published Standard 04/30/16 03/02/16 04/20/16 © 2016 Egan-Jones Proxy Services. All rights reserved. Meeting Information Meeting Type Annual Meeting Date 04/30/16 Record Date 03/02/16 Items & Recommendations We recommend that clients holding shares of BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC. vote: Management Item Egan-Jones Recommendation Recommendation 1 – Election of Directors FOR, WITH EXCEPTION OF FOR ALL Warren E. Buffett, Susan L. Decker, David S. Gottesman, Walter Scott, Jr., and Meryl B. Witmer 2 – Shareholder Proposal Regarding the AGAINST AGAINST Reporting of Risks Posed By Climate Change Considerations and Recommendations Egan-Jones' review centered on the Proposals in the context of maximizing shareholder value, based on publicly available information. Board and Compensation Rating Score Summary Ticker BRKB Company name BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY, INC. Board Rating Score Item TRUE/FALSE CEO and Chairman Separate FALSE Annual Director Elections TRUE One Class of Voting Stock Only FALSE Compensation Committee with All Independents TRUE Audit Committee with All Independents TRUE Nominating Committee with All Independents TRUE Non-binding Compensation Vote on Agenda FALSE Majority Independent Directors on Board TRUE Over-boarded CEO Director FALSE Over-boarded Non-CEO Director FALSE Major cyber security breach FALSE Failure to implement sufficient carbon risk plan FALSE Other financial or operational risk control failure FALSE Other -

Omaha, Nebraska | the Feminist Capitalist

METRO NEIGHBORHOOD NEWS OMAHA JOBS OMAHA CARS DISHOMAHA FLIPBOOK ADVERTISE CONTACT Home News Dish Music Arts Film Culture Style Specials Calendar Best Of « previous page the STORY The Reader > News The Feminist Capitalist No related articles. Advanced Search 8 Strategies on Women from Warren Buffett BY ROBERT P. MILES Looking out at the faces of people waiting to hear me discuss Warren Buffett’s investment strategies recently, I asked myself the same, but always unanswered, question the world’s greatest investor would himself ask: Where were the women? Buffett knows one thing other men tend to overlook — being a feminist is good for the bottom line. As an expert on Buffett’s business strategies, I travel the world speaking at major investment conferences. Buffett speaks at none, except for one. When senior editor-at-large Carol Loomis, one of his most trusted advisors since 1966, invites him to speak at Fortune’s Most Powerful Women Summit, Buffett says yes. Throughout the year, he also welcomes universities to send graduate students to question and learn from him, as long as one requirement is met: 30% or more must be female. Raised with two beloved sisters by a strong-willed mother, and father to a brilliant daughter himself, Buffett’s feminism isn’t just emotional, it’s pragmatic. He knows women own more than 10 million businesses with nearly two trillion dollars in sales each year. Those are numbers he pays attention to, and invests in. But Buffett is also highly aware that “winning the ovarian lottery,” as he calls it, gave him opportunities for success his sisters could not have. -

Congress As a Catalyst of Patent Reform at the Federal Circuit

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2014 Congress as a Catalyst of Patent Reform at the Federal Circuit Jonas Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Courts Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Legislation Commons ANDERSON.OFF.TO.WEBSITE (DO NOT DELETE) 6/23/2014 2:26 PM ARTICLES CONGRESS AS A CATALYST OF PATENT REFORM AT THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT JONAS ANDERSON* The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit is the dominant institution in patent law. The court’s control over patent law and policy has led to a host of academic proposals to shift power away from the court and towards other institutions, including the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and federal district courts. Surprisingly, however, academics have largely dismissed Congress as a potential institutional check on the Federal Circuit. Congress, it is felt, is too slow, too divided, and too beholden to special interests to effectively monitor changes in innovation and respond with appropriate reforms. This Article takes the opposite position. It proposes a prominent congressional role in patent policy, a role that extends beyond passing reform legislation. Congress’s relationship with the Federal Circuit is a dialogic one in which Congress often plays an initial role of catalyst and a final role of arbiter. Understanding Congress’s dialogic role in patent reform is not merely a theoretical exercise; this Article traces recent dialogic interactions between Congress and the Federal Circuit during the passage of the America Invents Act. -

1 Got Digital?: “Highly Digital” Defined

Got Digital?: Digital Matters Dig●it●tal [dij-i-tl] the translation of analog information (numbers, words, sounds, shapes, images, and more) into electronic data that can easily be stored and shared across networks and devices. Market Disruption. The digitization of information is upending traditional business models, changing the way people interact. Publishing: ebooks replacing paper (Borders run out of business) . Retail: online purchasing lowering brick-and-mortar sales . Music: artists selling directly through iTunes . Universal Impact. Every organization across every industry is impacted in some way. Marketing: “mass customization” of advertizing . Operations: supply-chain optimization . Customer Service: self-service . Growing Expectations of Corporate Leaders. Shareholders, employees and customers increasingly demanding that their leaders understand, leverage digital technologies effectively across the business. 1 Got Digital?: “Highly Digital” Defined “Highly Digital” companies satisfy …and are in short supply. four criteria… “Highly Digital” F500 Companies “Highly Digital” F100 Companies 2% 7% High % of Digital Revenue Sitting “Highly Digital” F100 Boards* CEO/Board Digital Leadership Channels 13% Experience Company Recognized as Transition Leader Highly Digital Board Examples: .Technology: Apple, Cisco, Dell, Google, H-P, Intel, Microsoft, Oracle Highly Digital Company Examples: Amazon, Apple, .Retail: Amazon, Walmart Cisco, Dell, eBay, Google, Microsoft, Oracle, Yahoo, .Financial Services: Berkshire Hathaway seven of which are in the F100. .Consumer: Procter & Gamble .Business Services: FedEx Source: Russell Reynolds Associates Analysis 2 Got Digital?: Key Findings . Disruption and digital status linked. For example, Technology and Retail well represented on the list. “Non-digital” companies boosting digital board status. For example, Berkshire Hathaway, Procter & Gamble and FedEx. Digital Boards Have 3 Common Themes: 1. -

Pursue Something Greater Campaign Donor Roll

Pursue Something Greater Campaign Donor Roll 3M Foundation Anne Abraham '15 A Different Path Gallery Thomas Abraham '86 Valerie Grossman Aarne '98 Thomas Abraham '91 Yonick Aaron '15 Alan Abrams '52 Marijana Ababovic James Abrams '70 Caitlin Abar Robert Abrams '82 Carolina Abarca '14 Shirley Abrams '70 Lourdes Abaunza '11 Thomas Abrams '14 Kreg Abbey '81 Lawrence Abreu Robin Abbey '87 Katherine Abt '12 Christine Dunn Abbott '84 Alexa Abubaker '14 Craig Abbott '90 ABVI Goodwill Edward Abbott David Abwender Ethel Maguire Abbott '56* Cindy Accordino Justin Abbott '13 Samuel Accordino '16 Susan Abbott Joseph Accorso '93 Abbott Laboratories Fund Ace Hardware Yousef Abdallatif '15 Joan Clark Aceto '54 Paul Abdo '76 Rudy Aceto '56 Stephen Abdo '79 Hector Acevedo '13 Gloria Abdulmateen '95 Heiddy Acevedo '13 Ali Abdulmateen '00 Carol Achilles '75 Jihan Abdurrafi '13 Joanne Acito Diane Abel '78 Christine Acker Abend & Silber PLLC Christopher Acker '02 Amanda Abraham '13 William Acker '02 Matt Ackerman '13 Phil and Lynn Adams Douglas and Helen Ackert Faye Adams '82 Helen Ackert Robb Adams '89 Merritt Ackles Robert Adams Nancy Ackles Stacy Adams '11 Cynthia Young Acklin '75 Tamara Adams '96 Dave and Barb Ackroyd Thomas Adams '13 Heather Acomb '09 Tina Trenkler Adams '94 Julia Acosta '12 William Adams '16 Joann Fininzio Acquarulo '94 Richard Adamus '59 Active Network, LLC Osei Adarkwa '14 Brian Adamo '13 Olusola David Adeniran '16 Barbara Franco Adams '69 Abisola Adeosun '11 Barbara Adams Beth Felo Adkins '86 Bruce Adams Gwen Adolph David Adams '13 -

Rraonleadership: the Year of the Digital Leader Rraonleadership: the Year of the Digital Leader

The Quarterly RRAonLeadership: The Year of the Digital Leader RRAonLeadership: The Year of the Digital Leader Welcome to the first issue of the RRA Quarterly—a collection of timely and thought-provoking articles, interviews and surveys that address the concerns of global leaders today. Our first issue focuses on perhaps the most disruptive force now at work in the business world: digital transformation. Managing digital transformation particularly is challenging because it requires companies to rethink what “digital” means in the first place and how they respond to it. Ten years ago, digital basically was a set of platforms and technologies—web sites and e-commerce and so on. Today, it’s not just entirely new products and services but, more important, a completely different set of relationships among companies, customers, suppliers and other stakeholders, driven by shared information, fluid decision making and flattened hierarchies. It tests not just what leaders do but what leaders are. The spoils go to those who can best imagine state-of-the-art products and creative relationships—and then successfully rewire their enterprises as needed. Not surprisingly, those with a track record of success at this are few and far between— and not always found in the places you might think.This issue’s articles on chief digital officers, digital leadership across the C-suite and the next generation of e-commerce grew out of our ongoing conversations with some of the world’s most innovative and successful executives. We hope these insights contribute to the discussions within your organization as well. The Quarterly Table of Contents 4 Do You Have the Digital Leaders You Need? These days, you can’t have a business conversation without discussing digital—social, local, mobile, big data, the cloud. -

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY ANNUAL MEETING 2020 Streamed By

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY ANNUAL MEETING 2020 Streamed by Yahoo Finance. Warren Buffett: This is the annual meeting of Berkshire Hathaway. It doesn’t look like an annual meeting. It doesn’t feel exactly like an annual meeting, and it particularly doesn’t feel like an annual meeting because my partner of 60 years, Charlie Munger, is not sitting up here. I think most of the people that come to our meeting really come to listen to Charlie. But I want to assure you, Charlie at 96 is in fine shape. His mind is as good as ever. His voice is as strong as ever, but it just didn’t seem like a good idea to have him make the trip to Omaha for this meeting. Charlie, Charlie is really taking to this new life. He’s added Zoom to his repertoire. So he has meetings every day with various people, and he’s just skipped right by me technologically. But that really isn’t such a huge achievement. It’s more like kind of stepping over a peanut or something. But nevertheless, I want to assure you, Charlie is in fine shape, and he’ll be back next year. We’ll try to have everything in the show that we normally have next year. Ajit Jain also, who is the vice chairman in charge of insurance, is safely in New York. Again, it just did not seem worthwhile for him to travel to Omaha for this meeting. But on my left we do have Greg Abel, and Greg is the vice chairman in charge of all operations except insurance.