Landmark Delirium Study JAMA.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

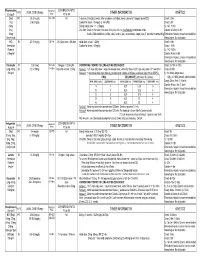

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Adjunctive Risperidone Treatment for Antidepressant-Resistant

Supplementary Online Content Krystal JH, Rosenheck RA, Cramer JA, et al. Adjunctive risperidone treatment for antidepressant- resistant symptoms of chronic military service–related PTSD. JAMA. 2011;306(5):493-502. eTable 1. Follow-up Drugs Started After Randomization eTable 2. Baseline Medications eTable 3. Number of Different Drugs From Each Major Class Each Patient Is Taking at Baseline eTable 4. Baseline Medication Combinations eTable 5. Adverse Events eFigure 1. Product-Limit Survival Estimates With Number of Subjects at Risk eFigure 2. Percentage of Veterans at Each CAPS Severity Level at 24 Weeks, by Treatment This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/23/2021 eTable 1. Follow-up Drugs Started After Randomization Placebo Risperidone N= 134 N= 133 Total Patients % Patients % Patients % p-value Drugs started after randomization 46 34.3 59 44.4 105 39.3 0.10 Adrenergic Drugs 4 3.0 5 3.8 9 3.4 0.75 Atenolol 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 Metoprolol 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Propranolol 1 0.7 1 0.8 2 0.7 Opiates 22 16.4 19 14.3 41 15.4 0.73 Codeine 1 0.7 1 0.8 2 0.7 Fentanyl 3 2.2 0 0.0 3 1.1 Hydrocodone (With Or Without 13 9.7 10 7.5 23 8.6 Acetaminophen) Methadone 1 0.7 0 0.0 1 0.4 Morphine 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Oxycodone (With Or Without 4 3.0 7 5.3 11 4.1 Acetaminophen) Tramadol 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Psycho-Stimulants 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 0.25 Methylphenidate 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 Muscle -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209 -

INVEGA SUSTENNA® (Paliperidone Palmitate)

INVEGA SUSTENNA® INVEGA SUSTENNA® (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable suspension, for intramuscular use --------------------------- DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS --------------------------- HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION Extended-release injectable suspension: 39 mg/0.25 mL, 78 mg/0.5 mL, 117 mg/0.75 mL, These highlights do not include all the information needed to use 156 mg/mL, or 234 mg/1.5 mL (3) INVEGA SUSTENNA® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for INVEGA SUSTENNA®. ----------------------------------- CONTRAINDICATIONS ----------------------------------- INVEGA SUSTENNA® (paliperidone palmitate) extended-release injectable Known hypersensitivity to paliperidone, risperidone, or to any excipients in suspension, for intramuscular use INVEGA SUSTENNA®. (4) Initial U.S. Approval: 2006 -----------------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ----------------------------- WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS • Cerebrovascular Adverse Reactions, Including Stroke, in Elderly Patients with WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS Dementia-Related Psychosis: Increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. reactions (e.g. stroke, transient ischemic attack). (5.2) • Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Manage with immediate discontinuation of Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drug and close monitoring. (5.3) drugs are -

Treatment of Adult Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Tool

Section: A B C D E F G Resources References Treatment of Adult Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Tool This tool is designed to support primary care providers in the treatment of adult patients (≥ 18 years) who have major depressive disorder (MDD). MDD is the most prevalent depressive disorder, and approximately 7% of Canadians meet the diagnostic criteria every year.1,2 The treatment of MDD involves psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy. Providers should work with patients to create a treatment plan together using providers’ clinical expertise and keeping in mind the patient’s preferences, as well as the practicality, feasibility, availability and affordability of treatment. TABLE OF CONTENTS pg. 1 Section A: Overview of MDD pathway pg. 6 Section E: Complementary and alternative medicine pg. 2 Section B: Assessing suicidality and managing pg. 7 Section F: Follow-up and monitoring suicide-related behaviour pg. 9 Section G: Special patient populations pg. 3 Section C: Psychotherapy options pg. 10 Resources pg.3 Section D: Pharmacotherapy management SECTION A: Overview of MDD pathway Patient has suspected depression Talking Points It is important to provide your patient with non-judgmental care (e.g. “Being Consider unexpected life events (e.g. death in the family, diagnosed with depression is nothing to be ashamed of, it is very common and change in family status, financial crisis). Consider special many adults are diagnosed with it every year”) patient populations. • Don’t use clinical/psychiatric language (e.g. “mental health,” “psychiatric,” and/or “maladaptive”) unless the patient uses these terms first • Use understandable language for cognitive distortions (e.g. -

Optimal Duration of Risperidone Or Olanzapine Adjunctive Therapy to Mood Stabilizer Following Remission of a Manic Episode: a CANMAT Randomized Double-Blind Trial

Molecular Psychiatry (2016) 21, 1050–1056 OPEN © 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/16 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Optimal duration of risperidone or olanzapine adjunctive therapy to mood stabilizer following remission of a manic episode: A CANMAT randomized double-blind trial LN Yatham1, S Beaulieu2, A Schaffer3, M Kauer-Sant’Anna4, F Kapczinski4, B Lafer5, V Sharma6, SV Parikh7, A Daigneault8, H Qian9, DJ Bond1, PH Silverstone10, N Walji1, R Milev11, P Baruch12, A da Cunha13, J Quevedo14, R Dias5, M Kunz4, LT Young15, RW Lam1 and H Wong16 Atypical antipsychotic adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate is effective in treating acute mania. Although continuation of atypical antipsychotic adjunctive therapy after mania remission reduces relapse of mood episodes, the optimal duration is unknown. As many atypical antipsychotics cause weight gain and metabolic syndrome, they should not be continued unless the benefits outweigh the risks. This 52-week double-blind placebo-controlled trial recruited patients with bipolar I disorder (n = 159) who recently remitted from a manic episode during treatment with risperidone or olanzapine adjunctive therapy to lithium or valproate. Patients were randomized to one of three conditions: discontinuation of risperidone or olanzapine and substitution with placebo at (i) entry (‘0-weeks’ group) or (ii) at 24 weeks after entry (‘24-weeks’ group) or (iii) continuation of risperidone or olanzapine for the full duration of the study (‘52-weeks’ group). The primary outcome measure was time to relapse of any mood episode. Compared with the 0-weeks group, the time to any mood episode was significantly longer in the 24-weeks group (hazard ratio (HR) 0.53; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.33, 0.86) and nearly so in the 52-weeks group (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.39, 1.02). -

When and How to Use Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics

Savvy Psychopharmacology When and how to use long-acting injectable antipsychotics William Klugh Kennedy, PharmD, BCPP, FASHP ong-acting injectable antipsychotics Understanding the similarities and dif- (LAIs) are a pharmacotherapeutic op- ferences among LAIs7 and potential inter- L tion to help clinicians individualize patient variability of each LAI allows pre- schizophrenia treatment. LAIs have been scribers to tailor the dosing regimen to the available since the 1960s, starting with flu- patient more safely and efficiently (Table, phenazine and later haloperidol; however, page 42).1,8-11 All LAI antipsychotic formu- second-generation antipsychotics were not lations rely on absorption pharmacokinet- Vicki L. Ellingrod, available in the United States until 20071,2 ics (PK) rather than elimination PK, which PharmD, BCPP, FCCP and more are in development (Box).3,4 generally is true for sustained-release oral Series Editor Up to one-half of patients with schizo- formulations as well. Absorption half-life phrenia do not adhere to their medica- duration and absorption half-life variabil- tions.5 LAI use may mitigate relapse in ity are key concepts in LAI dosing. acute schizophrenia that is caused by poor adherence to oral medications. LAIs may Clinical pearls have a lower risk of dose-related adverse Before prescribing an LAI, check that your effects because of lower peak antipsychotic patient has no known contraindications plasma levels and less variation between to the active drug or delivery method. peak and trough plasma levels. LAIs may Peak-related adverse effects typically are decrease the financial burden of schizo- not contraindications, although they may phrenia and increase individual quality prompt you to start at a lower dose. -

Aripiprazole Long-Acting Injection(Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole Long-acting Injection Aripiprazole Long-acting Injection (Abilify Maintena, ARISTADA) National Drug Monograph October 2013; Addendum March 2016 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The purpose of VA PBM Services drug monographs is to provide a comprehensive drug review for making formulary decisions. These documents will be updated when new clinical data warrant additional formulary discussion. Documents will be placed in the Archive section when the information is deemed to be no longer current. Executive Summary: Aripiprazole long-acting intramuscular injection (LAIM) is sixth antipsychotic and the fourth second generation antipsychotic to be marketed in a long-acting injection formulation. LAIM antipsychotics on the VA National Formulary: haloperidol and fluphenazine decanoate; risperidone; and paliperidone. Aripiprazole LAIM has FDA label indication for the treatment of schizophrenia. The initial and usual maintenance dose of aripiprazole is 400 mg once a month. The dose can be reduced to 300 mg or 200 mg monthly based on drug interactions or tolerability. Patients should have established tolerability to aripiprazole before receipt of the LAIM formulation. Oral aripiprazole, 10-30 mg/day, or another oral antipsychotic must be continued for 2-weeks after the initial dose, and then discontinued. Aripiprazole LAIM’s efficacy and safety are based on experience with the oral formulation as well as pharmacokinetic trials and a 52-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The randomized trial was terminated early because the difference in time to relapse met a predetermined statistically significant threshold (p=0.001) favoring aripiprazole LAIM [HR 5.03, 95% CI 3.15-8.02]. -

RISPERDAL® Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION ---------------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS-------------------- These highlights do not include all the information needed to use • Cerebrovascular events, including stroke, in elderly patients with RISPERDAL® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for dementia-related psychosis: RISPERDAL® is not approved for use in RISPERDAL®. patients with dementia-related psychosis. (5.2) • Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: Manage with immediate RISPERDAL® (risperidone) tablets, for oral use discontinuation of RISPERDAL® and close monitoring. (5.3) RISPERDAL® (risperidone) oral solution • Tardive dyskinesia: Consider discontinuing RISPERDAL® if clinically RISPERDAL® M-TAB® (risperidone) orally disintegrating tablets indicated. (5.4) Initial U.S. Approval: 1993 • Metabolic Changes: Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been associated WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular/ WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS cerebrovascular risk. These metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. dyslipidemia, and weight gain. (5.5) Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with o Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus: Monitor patients for antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death. RISPERDAL® is symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis. (5.1) polyphagia, and weakness. Monitor glucose regularly -

Chlorpromazine Versus Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs for Schizophrenia (Review)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Chlorpromazine versus atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia (Review) Saha KB, Bo L, Zhao S, Xia J, Sampson S, Zaman RU SahaKB, Bo L, ZhaoS, Xia J, Sampson S,ZamanRU. Chlorpromazine versus atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD010631. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010631.pub2. www.cochranelibrary.com Chlorpromazine versus atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia (Review) Copyright © 2016 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 8 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 9 METHODS ...................................... 9 RESULTS....................................... 15 Figure1. ..................................... 17 Figure2. ..................................... 24 Figure3. ..................................... 25 Figure4. ..................................... 27 ADDITIONALSUMMARYOFFINDINGS . 45 DISCUSSION ..................................... 52 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 54 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 55 REFERENCES ..................................... 55 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 65 DATAANDANALYSES. 150 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 CHLORPROMAZINE versus OLANZAPINE, Outcome 1 Clinical response: 1. No significant clinical response. 161 Analysis 1.2. Comparison -

Influence of Aripiprazole, Risperidone, and Amisulpride on Sensory and Sensorimotor Gating in Healthy &Lsquo

Neuropsychopharmacology (2014) 39, 2485–2496 & 2014 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/14 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Influence of Aripiprazole, Risperidone, and Amisulpride on Sensory and Sensorimotor Gating in Healthy ‘Low and High Gating’ Humans and Relation to Psychometry Philipp A Csomor1,4, Katrin H Preller*,1,4, Mark A Geyer2, Erich Studerus1,3, Theodor Huber1 and 1 Franz X Vollenweider 1Neuropsychopharmacology and Brain Imaging and Heffter Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, University Hospital of Psychiatry, Zu¨rich, Switzerland; 2Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA; 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland Despite advances in the treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders with atypical antipsychotics (AAPs), there is still need for compounds with improved efficacy/side-effect ratios. Evidence from challenge studies suggests that the assessment of gating functions in humans and rodents with naturally low-gating levels might be a useful model to screen for novel compounds with antipsychotic properties. To further evaluate and extend this translational approach, three AAPs were examined. Compounds without antipsychotic properties served as negative control treatments. In a placebo-controlled, within-subject design, healthy males received either single doses of aripiprazole and risperidone (n ¼ 28), amisulpride and lorazepam (n ¼ 30), or modafinil and valproate (n ¼ 30), and placebo. Prepulse inhibiton (PPI) and P50 suppression were assessed. Clinically associated symptoms were evaluated using the SCL-90-R. Aripiprazole, risperidone, and amisulpride increased P50 suppression in low P50 gaters. Lorazepam, modafinil, and valproate did not influence P50 suppression in low gaters. Furthermore, low P50 gaters scored significantly higher on the SCL-90-R than high P50 gaters. -

Comparison Between Combination of Risperidone and Haloperidol Therapy with Combination of Risperidone and Chlorpromazine Therapy

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 13, 2020 COMPARISON BETWEEN COMBINATION OF RISPERIDONE AND HALOPERIDOL THERAPY WITH COMBINATION OF RISPERIDONE AND CHLORPROMAZINE THERAPY ON CLINICAL SYMPTOM IMPROVEMENT OF SCHIZOPHRENIA Saidah Syamsuddin1, Erlyn Limoa2, Ismariani Mandan3, Sonny T. Lisal4 1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. 2Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. 3Postgraduate, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. 4Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. Received: 21.04.2020 Revised: 23.05.2020 Accepted: 18.06.2020 ABSTRACT: Background: Risperidone, haloperidol and chlorpromazine are antipsychotics that can easily be found in most hospitals but its use in combination does not yet have strong evidence especially to clinical symptom of schizophrenia patients. Objectives: This research aimed to know the difference between the combination of risperidone and haloperidol therapy with a combination of risperidone and chlorpromazine therapy on clinical symptom improvement of schizophrenia. Materials and methods: It used observational analytic design with prospective cohort approach. 30 subjects were divided into 2 groups where on 15 subjects who received a combination of risperidone and haloperidol therapy and 15 subjects received a combination of risperidone and chlorpromazine therapy. Improvement of clinical symptoms rated by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component (PANSS-EC) instrument at baseline and on the 1st day, on the 2nd day and on the 3rd day of therapy and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale – Excited Component (PANSS) instrument at baseline and on the 1st week, on the 2nd week on the 4th week, and on the 6th week of therapy.