Inclusion of Paliperidone and Risperidone (Long-Acting)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

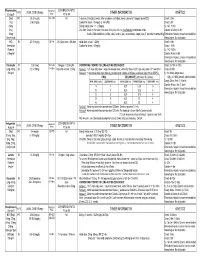

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Adjunctive Risperidone Treatment for Antidepressant-Resistant

Supplementary Online Content Krystal JH, Rosenheck RA, Cramer JA, et al. Adjunctive risperidone treatment for antidepressant- resistant symptoms of chronic military service–related PTSD. JAMA. 2011;306(5):493-502. eTable 1. Follow-up Drugs Started After Randomization eTable 2. Baseline Medications eTable 3. Number of Different Drugs From Each Major Class Each Patient Is Taking at Baseline eTable 4. Baseline Medication Combinations eTable 5. Adverse Events eFigure 1. Product-Limit Survival Estimates With Number of Subjects at Risk eFigure 2. Percentage of Veterans at Each CAPS Severity Level at 24 Weeks, by Treatment This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/23/2021 eTable 1. Follow-up Drugs Started After Randomization Placebo Risperidone N= 134 N= 133 Total Patients % Patients % Patients % p-value Drugs started after randomization 46 34.3 59 44.4 105 39.3 0.10 Adrenergic Drugs 4 3.0 5 3.8 9 3.4 0.75 Atenolol 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 Metoprolol 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Propranolol 1 0.7 1 0.8 2 0.7 Opiates 22 16.4 19 14.3 41 15.4 0.73 Codeine 1 0.7 1 0.8 2 0.7 Fentanyl 3 2.2 0 0.0 3 1.1 Hydrocodone (With Or Without 13 9.7 10 7.5 23 8.6 Acetaminophen) Methadone 1 0.7 0 0.0 1 0.4 Morphine 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Oxycodone (With Or Without 4 3.0 7 5.3 11 4.1 Acetaminophen) Tramadol 3 2.2 2 1.5 5 1.9 Psycho-Stimulants 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 0.25 Methylphenidate 0 0.0 2 1.5 2 0.7 Muscle -

Appendix 13C: Clinical Evidence Study Characteristics Tables

APPENDIX 13C: CLINICAL EVIDENCE STUDY CHARACTERISTICS TABLES: PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................ 3 APPENDIX 13C (I): INCLUDED STUDIES FOR INITIAL TREATMENT WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATION .................................. 4 ARANGO2009 .................................................................................................................................. 4 BERGER2008 .................................................................................................................................... 6 LIEBERMAN2003 ............................................................................................................................ 8 MCEVOY2007 ................................................................................................................................ 10 ROBINSON2006 ............................................................................................................................. 12 SCHOOLER2005 ............................................................................................................................ 14 SIKICH2008 .................................................................................................................................... 16 SWADI2010..................................................................................................................................... 19 VANBRUGGEN2003 .................................................................................................................... -

The Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Metabolic Function: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

The effects of antipsychotic treatment on metabolic function: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Toby Pillinger, Robert McCutcheon, Luke Vano, Katherine Beck, Guy Hindley, Atheeshaan Arumuham, Yuya Mizuno, Sridhar Natesan, Orestis Efthimiou, Andrea Cipriani, Oliver Howes ****PROTOCOL**** Review questions 1. What is the magnitude of metabolic dysregulation (defined as alterations in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride levels) and alterations in body weight and body mass index associated with short-term (‘acute’) antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia? 2. Does baseline physiology (e.g. body weight) and demographics (e.g. age) of patients predict magnitude of antipsychotic-associated metabolic dysregulation? 3. Are alterations in metabolic parameters over time associated with alterations in degree of psychopathology? 1 Searches We plan to search EMBASE, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE from inception using the following terms: 1 (Acepromazine or Acetophenazine or Amisulpride or Aripiprazole or Asenapine or Benperidol or Blonanserin or Bromperidol or Butaperazine or Carpipramine or Chlorproethazine or Chlorpromazine or Chlorprothixene or Clocapramine or Clopenthixol or Clopentixol or Clothiapine or Clotiapine or Clozapine or Cyamemazine or Cyamepromazine or Dixyrazine or Droperidol or Fluanisone or Flupehenazine or Flupenthixol or Flupentixol or Fluphenazine or Fluspirilen or Fluspirilene or Haloperidol or Iloperidone -

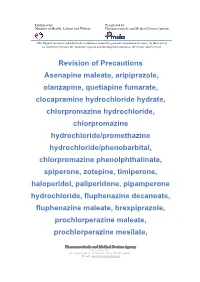

Revision of Precautions Asenapine Maleate, Aripiprazole, Olanzapine

Published by Translated by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency This English version is intended to be a reference material to provide convenience for users. In the event of inconsistency between the Japanese original and this English translation, the former shall prevail. Revision of Precautions Asenapine maleate, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine fumarate, clocapramine hydrochloride hydrate, chlorpromazine hydrochloride, chlorpromazine hydrochloride/promethazine hydrochloride/phenobarbital, chlorpromazine phenolphthalinate, spiperone, zotepine, timiperone, haloperidol, paliperidone, pipamperone hydrochloride, fluphenazine decanoate, fluphenazine maleate, brexpiprazole, prochlorperazine maleate, prochlorperazine mesilate, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Office of Safety I 3-3-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0013 Japan E-mail: [email protected] Published by Translated by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency This English version is intended to be a reference material to provide convenience for users. In the event of inconsistency between the Japanese original and this English translation, the former shall prevail. propericiazine, bromperidol, perphenazine, perphenazine hydrochloride, perphenazine fendizoate, perphenazine maleate, perospirone hydrochloride hydrate, mosapramine hydrochloride, risperidone (oral drug), levomepromazine hydrochloride, levomepromazine maleate March 27, 2018 Non-proprietary name Asenapine maleate, -

Formulary (List of Covered Drugs)

3ODQ<HDU 202 Formulary (List of Covered Drugs) PLEASE READ: THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS INFORMATION ABOUT THE DRUGS WE COVER IN THE FOLLOWING PLAN: $0 Cost Share AI/AN HMO Minimum Coverage HMO Silver 70 HMO Active Choice PPO Silver Opal 25 Gold HMO Silver 70 OFF Exchange HMO Amber 50 HMO Silver Opal 50 Silver HMO Silver 73 HMO Bronze 60 HDHP HMO Platinum 90 HMO Silver 87 HMO Bronze 60 HMO Ruby 10 Platinum HMO Silver 94 HMO Gold 80 HMO Ruby 20 Platinum HMO Jade 15 HMO Ruby 40 Platinum HMO This formulary was last updated on8//20. This formulary is VXEMHFWto change and all previous versions of the formulary no longer apply. For more recent information or other questions, please contact Chinese Community Health Plan Member Services at 1-888-775-7888 or, for TTY users, 1-877-681-8898, seven days a week from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., or visit www.cchphealthplan.com/family-member -,-ϭ -,-ϭ"&* !#" + 5 5 ),-$+" %(%'.')/"+#" %&/"+ -%/"$)% "%&/"+ *& )&! %&/"+ 0 $(#" '"+ %&/"+ *& %&/"+ %&/"+ +)(2" &-%(.' %&/"+ +)(2" .1&-%(.' %&/"+ )&! .1&-%(.' !" .1&-%(.' dŚŝƐĨŽƌŵƵůĂƌLJǁĂƐůĂƐƚƵƉĚĂƚĞĚ8ͬϭͬϮϬϮϭ͘dŚŝƐĨŽƌŵƵůĂƌLJŝƐƐƵďũĞĐƚƚŽ ĐŚĂŶŐĞĂŶĚĂůůƉƌĞǀŝŽƵƐǀĞƌƐŝŽŶƐŽĨƚŚĞĨŽƌŵƵůĂƌLJŶŽůŽŶŐĞƌĂƉƉůLJ͘&ŽƌŵŽƌĞ ƌĞĐĞŶƚŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƚŝŽŶŽƌŽƚŚĞƌƋƵĞƐƚŝŽŶƐ͕ƉůĞĂƐĞĐŽŶƚĂĐƚŚŝŶĞƐĞŽŵŵƵŶŝƚLJ ,ĞĂůƚŚWůĂŶDĞŵďĞƌ^ĞƌǀŝĐĞƐĂƚϭͲϴϴϴͲϳϳϱͲϳϴϴϴŽƌ͕ĨŽƌddzƵƐĞƌƐ͕ ϭͲϴϳϳͲϲϴϭͲϴϴϵϴ͕ƐĞǀĞŶĚĂLJƐĂǁĞĞŬĨƌŽŵϴ͗ϬϬĂ͘ŵ͘ƚŽϴ͗ϬϬƉ͘ŵ͕͘ŽƌǀŝƐŝƚ ǁǁǁ͘ĐĐŚƉŚĞĂůƚŚƉůĂŶ͘ĐŽŵͬĨĂŵŝůLJͲŵĞŵďĞƌ !! %+)&,+ &%+&+&)$,#)0),# *+666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666I % + &%*6666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666I -

Antipsychotics (Part-4) FLUOROBUTYROPHENONES

Antipsychotics (Part-4) FLUOROBUTYROPHENONES The fluorobutyrophenones belong to a much-studied class of compounds, with many compounds possessing high antipsychotic activity. They were obtained by structure variation of the analgesic drug meperidine by substitution of the N-methyl by butyrophenone moiety to produce the butyrophenone analogue which has similar activity as chlorpromazine. COOC2H5 N H3C Meperidine COOC2H5 N O Butyrophenone analog The structural requirements for antipsychotic activity in the group are well worked out. General features are expressed in the following structure. F AR Y O N • Optimal activity is seen when with an aromatic with p-fluoro substituent • When CO is attached with p-fluoroaryl gives optimal activity is seen, although other groups, C(H)OH and aryl, also give good activity. • When 3 carbons distance separates the CO from cyclic N gives optimal activity. • The aliphatic amino nitrogen is required, and highest activity is seen when it is incorporated into a cyclic form. • AR is an aromatic ring and is needed. It should be attached directly to the 4-position or occasionally separated from it by one intervening atom. • The Y group can vary and assist activity. An example is the hydroxyl group of haloperidol. The empirical SARs suggest that the 4-aryl piperidino moiety is superimposable on the 2-- phenylethylamino moiety of dopamine and, accordingly, could promote affinity for D2 receptors. The long N-alkyl substituent could help promote affinity and produce antagonistic activity. Some members of the class are extremely potent antipsychotic agents and D2 receptor antagonists. The EPS are extremely marked in some members of this class, which may, in part, be due to a potent DA block in the striatum and almost no compensatory striatal anticholinergic block. -

Paliperidone Long Acting Injection Patient Information

Paliperidone (pala-pera-done) long acting injection Patient Information - Hillmorton Hospital Pharmacy www.healthinfo.org.nz Why have I been prescribed paliperidone? Paliperidone is used to treat schizophrenia, psychosis and similar conditions. It can also be used to treat mania. A person diagnosed with schizophrenia may hear voices talking to them or about them. They may also become suspicious or paranoid. Some people also have problems with their thinking and feel that other people can read their thoughts. These are called “positive Paliperidone Injection Long Acting symptoms”. Paliperidone can help to relieve these symptoms. Many people with schizophrenia also experience “negative symptoms”. They feel tired and lacking in energy and may become quite inactive and withdrawn. Paliperidone may help relieve these symptoms as well. Paliperidone may also be prescribed for people who have had side effects such as strange movements and shaking, with older types of antipsychotics. Paliperidone is a close relative of the antipsychotic risperidone. It’s side effect profile is similar but has the advantage of being able to be given as a once a month injection. What exactly is paliperidone? Is paliperidone safe for me? It is usually safe to take paliperidone Paliperidone is one of a group of regularly as prescribed by your doctor, but medicines used to treat schizophrenia it doesn’t suit everyone. Let your doctor and similar disorders. These illnesses are know if any of the following apply to you, sometimes referred to as psychoses, as extra care may be needed: hence the name given to this group of medicines, which is the “antipsychotics”. -

A Nested Case–Control Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Golestan University of Medical Sciences Repository Schizophrenia Research 150 (2013) 416–420 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Schizophrenia Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/schres Medication and suicide risk in schizophrenia: A nested case–control study Johan Reutfors a,⁎, Shahram Bahmanyar a,b, Erik G. Jönsson c, Lena Brandt a, Robert Bodén a,d, Anders Ekbom a, Urban Ösby e,f a Centre for Pharmacoepidemiology (CPE), Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden b Faculty of Medicine, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran c Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden d Department of Neuroscience, Psychiatry, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden e Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences, and Society, Centre of Family Medicine (CeFAM), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden f Department of Psychiatry, Tiohundra AB, Norrtälje, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Introduction: Patients with schizophrenia are at increased risk of suicide, but data from controlled studies of Received 16 June 2013 pharmacotherapy in relation to suicide risk is limited. Received in revised form 28 August 2013 Aim: To explore suicide risk in schizophrenia in relation to medication with antipsychotics, antidepressants, Accepted 9 September 2013 and lithium. Available online 2 October 2013 Methods: Of all patients with a first clinical discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in Stockholm County between 1984 and 2000 (n = 4000), patients who died by suicide within five years Keywords: from diagnosis were defined as cases (n = 84; 54% male). Individually matched controls were identified Schizophrenia Suicide from the same population. -

Antipsychotics and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death

ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Antipsychotics and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death Sabine M. J. M. Straus, MD; Gyse`le S. Bleumink, MD; Jeanne P. Dieleman, PhD; Johan van der Lei, MD, PhD; Geert W. ‘t Jong, PhD; J. Herre Kingma, MD, PhD; Miriam C. J. M. Sturkenboom, PhD; Bruno H. C. Stricker, PhD Background: Antipsychotics have been associated with Results: The study population comprised 554 cases of prolongation of the corrected QT interval and sudden car- sudden cardiac death. Current use of antipsychotics was diac death. Only a few epidemiological studies have in- associated with a 3-fold increase in risk of sudden car- vestigated this association. We performed a case- diac death. The risk of sudden cardiac death was high- control study to investigate the association between use est among those using butyrophenone antipsychotics, of antipsychotics and sudden cardiac death in a well- those with a defined daily dose equivalent of more than defined community-dwelling population. 0.5 and short-term (Յ90 days) users. The association with current antipsychotic use was higher for witnessed cases Methods: We performed a population-based case-control (n=334) than for unwitnessed cases. study in the Integrated Primary Care Information (IPCI) project, a longitudinal observational database with com- Conclusions: Current use of antipsychotics in a gen- plete medical records from 150 general practitioners. All eral population is associated with an increased risk of sud- instances of death between January 1, 1995, and April 1, den cardiac death, even at a low dose and for indica- 2001, were reviewed. Sudden cardiac death was classified tions other than schizophrenia. -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209 -

Second-Generation Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics: a PRACTICAL GUIDE Understanding Each of These Medications’ Unique Properties Can Optimize Patient Care

Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: A PRACTICAL GUIDE Understanding each of these medications’ unique properties can optimize patient care Brittany L. Parmentier, PharmD, MPH, here are currently 7 FDA-approved second-generation long-acting BCPS, BCPP 1-7 Clinical Assistant Professor injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs). These LAIAs provide a Department of Pharmacy Practice Tunique dosage form that allows patients to receive an antipsy- The University of Texas at Tyler Fisch College of Pharmacy chotic without taking oral medications every day, or multiple times per Tyler, Texas day. This may be an appealing option for patients and clinicians, but Disclosure The author reports no financial relationships with any because there are several types of LAIAs available, it may be difficult to companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with determine which LAIA characteristics are best for a given patient. manufacturers of competing products. Since the FDA approved the first second-generation LAIA, risperidone long-acting injectable (LAI),1 in 2003, 6 additional second-generation LAIAs have been approved: • aripiprazole LAI • aripiprazole lauroxil LAI • olanzapine pamoate LAI • paliperidone palmitate monthly injection • paliperidone palmitate 3-month LAI • risperidone LAI for subcutaneous (SQ) injection. When discussing medication options with patients, clinicians need to consider factors that are unique to each LAIA. In this article, I describe the similarities and differences among the second-generation LAIAs, and address common questions about these medications. A major potential benefit: Increased adherence One potential benefit of all LAIAs is increased medication adherence com- pared with oral antipsychotics. One meta-analysis of 21 randomized con- trolled trials (RCTs) that compared LAIAs with oral antipsychotics and Current Psychiatry GEORGE MATTEI/SCIENCE SOURCE GEORGE MATTEI/SCIENCE Vol.