Grand Canyon National Park Foundation Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) Depository) 11-19-2004 Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement Bureau of Land Management Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Bureau of Land Management, "Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement" (2004). All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository). Paper 77. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/77 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bureau of Land Management Phone 435.644.4300 Grand Staircase-Escalante NM 190 E. Center Street Fax 435.644.4350 Kanab, UT 84741 Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area Wildlife Habitat Improvement Version: 19 November 2004 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................... 3 A. Background and Need for Management Activity ................................................................... 3 B. Purpose ..................................................................................................................................... -

Sell-1536, Field Trip Notes, , MILS

CONTACT INFORMATION Mining Records Curator Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., Suite 100 Tucson, Arizona 85701 520-770-3500 http://www.azgs.az.gov [email protected] The following file is part of the James Doyle Sell Mining Collection ACCESS STATEMENT These digitized collections are accessible for purposes of education and research. We have indicated what we know about copyright and rights of privacy, publicity, or trademark. Due to the nature of archival collections, we are not always able to identify this information. We are eager to hear from any rights owners, so that we may obtain accurate information. Upon request, we will remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. CONSTRAINTS STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey does not claim to control all rights for all materials in its collection. These rights include, but are not limited to: copyright, privacy rights, and cultural protection rights. The User hereby assumes all responsibility for obtaining any rights to use the material in excess of “fair use.” The Survey makes no intellectual property claims to the products created by individual authors in the manuscript collections, except when the author deeded those rights to the Survey or when those authors were employed by the State of Arizona and created intellectual products as a function of their official duties. The Survey does maintain property rights to the physical and digital representations of the works. QUALITY STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey is not responsible for the accuracy of the records, information, or opinions that may be contained in the files. The Survey collects, catalogs, and archives data on mineral properties regardless of its views of the veracity or accuracy of those data. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

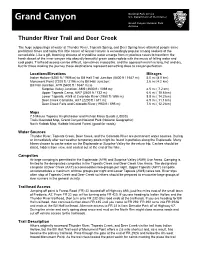

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of falling water and cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (good for roads) Water Sources Thunder River, Tapeats Creek, Deer Creek, and the Colorado River are permanent water sources. -

Grand Canyon

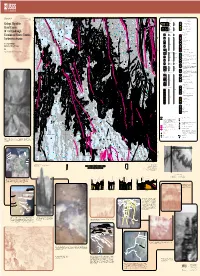

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Grand Canyon Supergroup, Northern Arizona

Unconformity at the Cardenas-Nankoweap contact (Precambrian), Grand Canyon Supergroup, northern Arizona DONALD P. ELSTON I U.S. Geological Survey, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 G. ROBERT SCOTT* ' ABSTRACT sedimentary and volcanic rocks about Group (Noble, 1914) and overlying strata 4,000 m thick overlies crystalline basement of the Chuar Group (Ford and Breed, Red-bed strata of the Nankoweap For- rocks (—1.7 b.y. old; Pasteels and Silver, 1973). Because the Nankoweap had not mation unconformably overlie the 1965). These strata, in turn, are overlain by been subdivided into named formations, —l,100-m.y.-old Cardenas Lavas of the sandstone of Early and Middle Cambrian Maxson (1961) reduced the Nankoweap to Unkar Group in the eastern Grand Canyon. age. Near the middle of the series, a 300- formational rank and renamed it the Nan- An unconformity and an apparent discon- m-thick section of basaltic lava flows is un- koweap Formation, a usage herein adopted formity are present. At most places the conformably overlain by about 100 m of (Art. 9a, 15c, American Commission on upper member of the Nankoweap overlies red-brown and purplish sandstone and Stratigraphic Nomenclature, 1961). The the Cardenas, and locally an angular dis- siltstone. The lavas — named the Cardenas Grand Canyon Series of Walcott (1894) cordance can be recognized that reflects the Lavas or Cardenas Lava Series by Keyes thus consists of three distinct major units; truncation of 60 m of Cardenas. This un- (1938), and adopted as the Cardenas Lavas they are, in ascending order, the Unkar conformity also underlies a newly recog- by Ford and others (1972) — and the over- Group, Nankoweap Formation, and Chuar nized ferruginous sandstone of probable lying red sandstone were included in the Group; this series is here redesignated the local extent that underlies the upper upper part of Walcott's (1894) Precam- Grand Canyon Supergroup, as current member and that herein is called the fer- brian Unkar terrane. -

Pinyon-Juniper Woodland

Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historic and Current Landscape Conditions for Potential Natural Vegetation Types of the Southwest Southwest Forest Assessment Project 2006 Preferred Citation: Introduction to the Historic Range of Variation Schussman, Heather and Ed Smith. 2006. Historical Range of Variation for Potential Natural Vegetation Types of the Southwest. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 22 pp. Introduction to Vegetation Modeling Schussman, Heather and Ed Smith. 2006. Vegetation Models for Southwest Vegetation. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 11 pp. Semi-Desert Grassland Schussman, Heather. 2006. Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historical and Current Landscape Conditions for Semi-Desert Grassland of the Southwestern U.S. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 53 pp. Madrean Encinal Schussman, Heather. 2006. Historical Range of Variation for Madrean Encinal of the Southwestern U.S. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 16 pp. Interior Chaparral Schussman, Heather. 2006. Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historical and Current Landscape Conditions for Interior Chaparral of the Southwestern U.S. Prepared for the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Southwestern Region by The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, AZ. 24 pp. Madrean Pine-Oak Schussman, Heather and Dave Gori. 2006. Historical Range of Variation and State and Transition Modeling of Historical and Current Landscape Conditions for Madrean Pine-Oak of the Southwestern U.S. -

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of water falling into cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Updates and Closures Climbing and/or rappelling in the creek narrows, with or without the use of ropes or other technical equipment is prohibited. This restriction extends within the creek beginning at the southeast end of the rock ledges, known as the “Patio” to the base of Deer Creek Falls. The trail from the river to hiker campsites and points up-canyon remains open. This restriction is necessary for the protection of significant cultural resources. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (USDA) Trailhead Access Leave the pavement on Forest Service Road (FSR) 22. -

Walking Guide

Grand Canyon National Park Trail of Time National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Walking Guide Find these markers and find these views along the 2 km (1.2 mile) timeline trail. Each one represents a key time in this region’s geologic history. Yavapai Observation Station and the Park geology brochure have additional information about all the Grand Canyon rock layers. Canyon Carving last 6 million years Colorado River Find the Colorado River deep in the canyon. This mighty river has carved the Grand Canyon in “only” the last six million years. Upper Flat Layers 270–315 million years old Kaibab (KIE-bab) Formation Toroweap (TORO-weep) Formation Coconino (coco-KNEE-no) Sandstone Hermit Formation Supai (SOO-pie) Group You are standing on the top rock layer, called the Kaibab Formation. It was deposited 270 million years ago in a shallow sea. From this point you can see lower (older) layers too. The Trail of Time is a joint project of Grand Canyon National Park, the University of New Mexico, and the National Science Foundation Grand Canyon National Park Trail of Time National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Walking Guide Lowest Flat Layer younger layers above 525 million years old older layers below Tapeats (ta-PEETS) Sandstone Your best view of the Tapeats Sandstone is from marker 590. But it is actually 525 million years old. It is the oldest of the horizontal rock layers, but not the oldest rock in the canyon. Supergroup 742–1,255 million years old Hakatai (HACK-a-tie) Shale Find the bright orange Hakatai Shale. -

Grand Canyon Provenance for Orthoquartzite Clasts in the Lower Miocene of Coastal Southern California GEOSPHERE

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Grand Canyon provenance for orthoquartzite clasts in the lower Miocene of coastal southern California 1 1 2 3 4 1 GEOSPHERE, v. 15, no. X Leah Sabbeth , Brian P. Wernicke , Timothy D. Raub , Jeffery A. Grover , E. Bruce Lander , and Joseph L. Kirschvink 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Boulevard, MC 100-23, Pasadena, California 91125, USA 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, Scotland, UK KY16 9AJ https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02111.1 3Department of Physical Sciences, Cuesta College, San Luis Obispo, California 93403-8106, USA 4Paleo Environmental Associates, Inc., Altadena, California 91101-3205, USA 14 figures; 6 tables; 2 sets of supplemental files CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] ABSTRACT sandstones. Collectively, these data define a mid-Tertiary, SW-flowing “Arizona River” drainage system between the rapidly eroding eastern Grand Canyon CITATION: Sabbeth, L., Wernicke, B.P., Raub, T.D., Grover, J.A., Lander, E.B., and Kirschvink, J.L., Orthoquartzite detrital source regions in the Cordilleran interior yield region and coastal California. 2019, Grand Canyon provenance for orthoquartzite clast populations with distinct spectra of paleomagnetic inclinations and clasts in the lower Miocene of coastal southern Cal- detrital zircon ages that can be used to trace the provenance of gravels ifornia: Geosphere, v. 15, no. X, p. 1–26, https://doi. org/10.1130/GES02111.1. deposited along the western margin of the Cordilleran orogen. An inventory ■ INTRODUCTION of characteristic remnant magnetizations (CRMs) from >700 sample cores Science Editor: Andrea Hampel from orthoquartzite source regions defines a low-inclination population of Among the most difficult problems in geology is constraining the kilome- Associate Editor: James A.