The Black Devil Called Ergot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies

agronomy Review Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies Sofia Agriopoulou Department of Food Science and Technology, University of the Peloponnese, Antikalamos, 24100 Kalamata, Greece; [email protected]; Tel.: +30-27210-45271 Abstract: Ergot alkaloids (EAs) are a group of mycotoxins that are mainly produced from the plant pathogen Claviceps. Claviceps purpurea is one of the most important species, being a major producer of EAs that infect more than 400 species of monocotyledonous plants. Rye, barley, wheat, millet, oats, and triticale are the main crops affected by EAs, with rye having the highest rates of fungal infection. The 12 major EAs are ergometrine (Em), ergotamine (Et), ergocristine (Ecr), ergokryptine (Ekr), ergosine (Es), and ergocornine (Eco) and their epimers ergotaminine (Etn), egometrinine (Emn), egocristinine (Ecrn), ergokryptinine (Ekrn), ergocroninine (Econ), and ergosinine (Esn). Given that many food products are based on cereals (such as bread, pasta, cookies, baby food, and confectionery), the surveillance of these toxic substances is imperative. Although acute mycotoxicosis by EAs is rare, EAs remain a source of concern for human and animal health as food contamination by EAs has recently increased. Environmental conditions, such as low temperatures and humid weather before and during flowering, influence contamination agricultural products by EAs, contributing to the Citation: Agriopoulou, S. Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and appearance of outbreak after the consumption of contaminated products. The present work aims to Cereal-Derived Food Products: present the recent advances in the occurrence of EAs in some food products with emphasis mainly Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, on grains and grain-based products, as well as their toxicity and control strategies. -

The Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances

The Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances Draft Guidelines and Reference Material for Public Health Services To be used to assist in a pilot study from July – December 2001 April 2001 Jeff Fowles, Ph.D. Prepared by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, Limited Under contract by the New Zealand Ministry of Health DISCLAIMER This report or document ("the Report") is given by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited ("ESR") solely for the benefit of the Ministry of Health, Public Health Service Providers and other Third Party Beneficiaries as defined in the Contract between ESR and the Ministry of Health, and is strictly subject to the conditions laid out in that Contract. Neither ESR nor any of its employees makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for use of the Report or its contents by any other person or organisation. Guidelines for the Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances April 2001 Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Dr Michael Bates and Melissa Perks (ESR), Sally Gilbert and Helen Saba (Ministry of Health), Dr Donald Campbell (Midcentral Health), Dr Deborah Read (ERMANZ), and Dr Nerida Smith (National Poisons Centre) for useful contributions and helpful suggestions on the construction of these guidelines. Guidelines for the Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances April 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................1 -

A Comprehensive Look at the Salem Witch Mania of 1692 Ashley Layhew

The Devil’s in the Details: A Comprehensive Look at the Salem Witch Mania of 1692 __________ Ashley Layhew Nine-year-old Betty Parris began to convulse, seize, and scream gibber- ish in the winter of 1692. The doctor pronounced her bewitched when he could find no medical reason for her actions. Five other girls began ex- hibiting the same symptoms: auditory and visual hallucinations, fevers, nausea, diarrhea, epileptic fits, screaming, complaints of being bitten, poked, pinched, and slapped, as well as coma-like states and catatonic states. Beseeching their Creator to ease the suffering of the “afflicted,” the Puritans of Salem Village held a day of fasting and prayer. A relative of Betty’s father, Samuel Parris, suggested a folk cure, in which the urine of the afflicted girls was taken and made into a cake. The villagers fed the cake to a dog, as dogs were believed to be the evil helpers of witches. This did not work, however, and the girls were pressed to name the peo- ple who were hurting them.1 The girls accused Tituba, a Caribbean slave who worked in the home of Parris, of being the culprit. They also accused two other women: Sarah Good and Sarah Osbourne. The girls, all between the ages of nine and sixteen, began to accuse their neighbors of bewitching them, saying that three women came to them and used their “spectres” to hurt them. The girls would scream, cry, and mimic the behaviors of the accused when they had to face them in court. They named many more over the course of the next eight months; the “bewitched” youth accused a total of one hundred and forty four individuals of being witches, with thirty sev- en of those executed following a trial. -

Hallucinogens: a Cause of Convulsive Ergot Psychoses

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 6-1976 Hallucinogens: a Cause of Convulsive Ergot Psychoses Sylvia Dahl Winters Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Psychiatry Commons Recommended Citation Winters, Sylvia Dahl, "Hallucinogens: a Cause of Convulsive Ergot Psychoses" (1976). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 976. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/976 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT HALLUCINOGENS: A CAUSE OF CONVULSIVE ERGOT PSYCHOSES By Sylvia Dahl Winters Ergotism with vasoconstriction and gangrene has been reported through the centuries. Less well publicized are the cases of psychoses associated with convulsive ergotism. Lysergic acid amide a powerful hallucinogen having one.-tenth the hallucinogenic activity of LSD-25 is produced by natural sources. This article attempts to show that convulsive ergot psychoses are mixed psychoses caused by lysergic acid amide or similar hallucinogens combined with nervous system -

615.9Barref.Pdf

INDEX Abortifacient, abortifacients bees, wasps, and ants ginkgo, 492 aconite, 737 epinephrine, 963 ginseng, 500 barbados nut, 829 blister beetles goldenseal blister beetles, 972 cantharidin, 974 berberine, 506 blue cohosh, 395 buckeye hawthorn, 512 camphor, 407, 408 ~-escin, 884 hypericum extract, 602-603 cantharides, 974 calamus inky cap and coprine toxicity cantharidin, 974 ~-asarone, 405 coprine, 295 colocynth, 443 camphor, 409-411 ethanol, 296 common oleander, 847, 850 cascara, 416-417 isoxazole-containing mushrooms dogbane, 849-850 catechols, 682 and pantherina syndrome, mistletoe, 794 castor bean 298-302 nutmeg, 67 ricin, 719, 721 jequirity bean and abrin, oduvan, 755 colchicine, 694-896, 698 730-731 pennyroyal, 563-565 clostridium perfringens, 115 jellyfish, 1088 pine thistle, 515 comfrey and other pyrrolizidine Jimsonweed and other belladonna rue, 579 containing plants alkaloids, 779, 781 slangkop, Burke's, red, Transvaal, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, 453 jin bu huan and 857 cyanogenic foods tetrahydropalmatine, 519 tansy, 614 amygdalin, 48 kaffir lily turpentine, 667 cyanogenic glycosides, 45 lycorine,711 yarrow, 624-625 prunasin, 48 kava, 528 yellow bird-of-paradise, 749 daffodils and other emetic bulbs Laetrile", 763 yellow oleander, 854 galanthamine, 704 lavender, 534 yew, 899 dogbane family and cardenolides licorice Abrin,729-731 common oleander, 849 glycyrrhetinic acid, 540 camphor yellow oleander, 855-856 limonene, 639 cinnamomin, 409 domoic acid, 214 rna huang ricin, 409, 723, 730 ephedra alkaloids, 547 ephedra alkaloids, 548 Absorption, xvii erythrosine, 29 ephedrine, 547, 549 aloe vera, 380 garlic mayapple amatoxin-containing mushrooms S-allyl cysteine, 473 podophyllotoxin, 789 amatoxin poisoning, 273-275, gastrointestinal viruses milk thistle 279 viral gastroenteritis, 205 silibinin, 555 aspartame, 24 ginger, 485 mistletoe, 793 Medical Toxicology ofNatural Substances, by Donald G. -

The Case of Elizabeth Howe

Walton 1 Claire Walton HIST 2090 29 November 2017 Final Paper A Pious Woman Condemned by Rumor, Church, and Court: The Case of Elizabeth Howe “Though shee wer condemned before men shee was Justefyed befor god”1 -Goody Safford Prior to the year 1682, Goody Elizabeth Howe enjoyed a reputation defined by piety, honesty, and neighborliness. Two distinct disputes in 1682 would come together ten years later during the Salem witch crisis to place Elizabeth’s life in mortal peril. A “faling [out]” between Samuel Perley and the Howes preceded fits suffered by Samuel’s daughter, who reportedly identified Elizabeth as her tormentor. Although ministerial accounts contested Elizabeth’s culpability, rumors spread and stained Elizabeth’s holy reputation. Her rejection from the Ipswich Church approximately two or three years later, informed by the rumor of witchcraft and other reports from neighbors, exacerbated suspicion, as those involved in the church’s decision attributed maleficium to Elizabeth.2 The second dispute occurred on June 14, 1682, the same year Samuel Perley’s daughter first reported afflictions. The Topsfield men, Thomas Baker, Jacob Towne, and John Howe, Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, challenged John Putnam of Salem Village over his claim to land along the Ipswich River. This dispute pitted the Howe family against the Putnam family, a driving force behind the Salem witch trials of 1692. Ultimately, Elizabeth’s reputation of witchcraft coupled with her relationship to John Howe and by extension association with the Putnam land dispute influenced her conviction as a witch. Although numerous individuals 1 Bernard Rosenthal, et al., eds., Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 341 (Hereafter RSWH). -

Question of the Day Archives: Monday, December 5, 2016 Question: Calcium Oxalate Is a Widespread Toxin Found in Many Species of Plants

Question Of the Day Archives: Monday, December 5, 2016 Question: Calcium oxalate is a widespread toxin found in many species of plants. What is the needle shaped crystal containing calcium oxalate called and what is the compilation of these structures known as? Answer: The needle shaped plant-based crystals containing calcium oxalate are known as raphides. A compilation of raphides forms the structure known as an idioblast. (Lim CS et al. Atlas of select poisonous plants and mushrooms. 2016 Disease-a-Month 62(3):37-66) Friday, December 2, 2016 Question: Which oral chelating agent has been reported to cause transient increases in plasma ALT activity in some patients as well as rare instances of mucocutaneous skin reactions? Answer: Orally administered dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) has been reported to cause transient increases in ALT activity as well as rare instances of mucocutaneous skin reactions. (Bradberry S et al. Use of oral dimercaptosuccinic acid (succimer) in adult patients with inorganic lead poisoning. 2009 Q J Med 102:721-732) Thursday, December 1, 2016 Question: What is Clioquinol and why was it withdrawn from the market during the 1970s? Answer: According to the cited reference, “Between the 1950s and 1970s Clioquinol was used to treat and prevent intestinal parasitic disease [intestinal amebiasis].” “In the early 1970s Clioquinol was withdrawn from the market as an oral agent due to an association with sub-acute myelo-optic neuropathy (SMON) in Japanese patients. SMON is a syndrome that involves sensory and motor disturbances in the lower limbs as well as visual changes that are due to symmetrical demyelination of the lateral and posterior funiculi of the spinal cord, optic nerve, and peripheral nerves. -

Utilization of Bone Scan and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography on Amputation Planning in Acute Microvascular Injury: Two Cases T

The Foot 40 (2019) 109–115 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Foot journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foot Case Report Utilization of bone scan and single photon emission computed tomography on amputation planning in acute microvascular injury: Two cases T Michael Huchitala,c,*, Andrew Aub,Jeffrey V. Lucidoc,d a North Jersey Reconstructive Foot and Ankle Fellowship, United States b California School of Podiatric Medicine, United States c NYU Langone Medical Center, United States d NYU Langone Brooklyn-Chief of Podiatry, United States ABSTRACT The use of single photon emission computer tomography (SPECT/CT) in acute vascular injury is not well documented. SPECT/CT combines the anatomic detail of computer tomography with the functional vascular perfusion of photon emission to determine the viability of osseous structures and surrounding soft tissue. The superimposed imaging provides the practitioner with a reliable anatomic image of viability of a specific anatomic area following insult or injury. We present two cases, bilateral lower extremity frostbite, and symmetric peripheral gangrene in which this imaging modality provided guidance for surgical intervention with adequate predictability and results. 1. Introduction damage [2]. Classically, there are four phases of cold induced thermal injury [2]. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT/CT) com- The first phase is hallmarked by local vasoconstriction with resultant bines the use of a radiotracer to visualize functional blood flow to tis- paresthesia leading to a superficial skin desquamation. The second sues and organs with the anatomically detailed cross sectional images of phase involves intracellular and extracellular ice crystal formation that a computerized tomography scan. -

A Short History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Trials : Illustrated by A

iiifSj irjs . Elizabeth Howe's Trial Boston Medical Library 8 The Fenway to H to H Ex LlBRIS to H to H William Sturgis Bigelow to H to H to to Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/shorthistoryofsaOOperl . f : II ' ^ sfti. : ; Sf^,x, )" &*% "X-':K -*. m - * -\., if SsL&SfT <gHfe'- w ^ 5? '•%•; ..^ II ,».-,< s «^~ « ; , 4 r. #"'?-« •^ I ^ 1 '3?<l» p : :«|/t * * ^ff .. 'fid p dji, %; * 'gliif *9 . A SHORT HISTORY OF THE Salem Village Witchcraft Trials ILLUSTRATED BT A Verbatim Report of the Trial of Mrs. Elizabeth Howe A MEMORIAL OF HER To dance with Lapland witches, while the lab'ring moon eclipses at their charms. —Paradise Lost, ii. 662 MAP AND HALF TONE ILLUSTRATIONS SALEM, MASS.: M. V. B. PERLEY, Publisher 1911 OPYBIGHT, 1911 By M. V. B. PERLEY Saeem, Mass. nJtrt^ BOSTON 1911 NOTICE Greater Salem, the province of Governors Conant and Endicott, is visited by thousands of sojourners yearly. They come to study the Quakers and the witches, to picture the manses of the latter and the stately mansions of Salem's commercial kings, and breathe the salubrious air of "old gray ocean." The witchcraft "delusion" is generally the first topic of inquiry, and the earnest desire of those people with notebook in hand to aid the memory in chronicling answers, suggested this monograph and urged its publication. There is another cogent reason: the popular knowledge is circumscribed and even that needs correcting. This short history meets that earnest desire; it gives the origin, growth, and death of the hideous monster; it gives dates, courts, and names of places, jurors, witnesses, and those hanged; it names and explains certain "men and things" that are concomitant to the trials, with which the reader may not be conversant and which are necessary to the proper setting of the trials in one's mind; it compasses the salient features of witchcraft history, so that the story of the 1692 "delusion" may be garnered and entertainingly rehearsed. -

The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: the Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: The Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered Susan Kay Ocksreider College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Law Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ocksreider, Susan Kay, "The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: The Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625278. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7p31-h828 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS FROM A LEGAL PERSPECTIVE; THE IMPORTANCE OF SPECTRAL EVIDENCE RECONSIDERED A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of Williams and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan K. Ocksreider 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626505 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626505 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). -

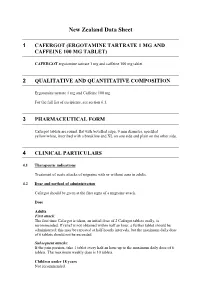

New Zealand Data Sheet

New Zealand Data Sheet 1 CAFERGOT (ERGOTAMINE TARTRATE 1 MG AND CAFFEINE 100 MG TABLET) CAFERGOT ergotamine tartrate 1 mg and caffeine 100 mg tablet 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Ergotamine tartrate 1 mg and Caffeine 100 mg For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Cafergot tablets are round, flat with bevelled edge, 9 mm diameter, speckled yellow/white, inscribed with a breakline and XL on one side and plain on the other side. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Treatment of acute attacks of migraine with or without aura in adults. 4.2 Dose and method of administration Cafergot should be given at the first signs of a migraine attack. Dose Adults First attack: The first time Cafergot is taken, an initial dose of 2 Cafergot tablets orally, is recommended. If relief is not obtained within half an hour, a further tablet should be administered; this may be repeated at half-hourly intervals, but the maximum daily dose of 6 tablets should not be exceeded. Subsequent attacks: If the pain persists, take 1 tablet every half an hour up to the maximum daily dose of 6 tablets. The maximum weekly dose is 10 tablets. Children under 18 years Not recommended. Maximum dose per attack or per day Adults: 6 mg ergotamine tartrate = 6 tablets. Maximum weekly dose Adults: 10 mg ergotamine tartrate = 10 tablets. Special populations Renal impairment Cafergot is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (see Contraindications). Hepatic impairment Cafergot is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment (see Contraindications). -

The Black Devil Called Ergot

The Black Devil Called Ergot Joseph Featherly Due: December 6, 2010 History 2090 Professor Mary Beth Norton Featherly | 1 The Black Devil Called Ergot The hypothesis that a certain fungus, known as ergot, might be somehow connected to the events occurring around Salem Village in 1691/2 has been controversial. The article “Ergotism: Satan Loose in Salem,” by Linnda R. Caporael was introduced in April of 1976 with a compelling story of a chemical induced hysteria resulting in the Salem witch trials. However, very shortly afterwards her work was heavily criticized by psychologists Nicholas P. Spanos and Jack Gottlieb in their December 1976 article, “Ergotism and the Salem Witch Trials.” The topic from then on remained muted until 1989 when Mary K. Matossian revisited the subject in her book, Poisons of the Past: Molds, Epidemics, and History. Matossian made a compelling argument favoring ergot’s role in Salem gruesome past. Reevaluation of historical documents and also the analysis of previously overlooked climate and agricultural accounts provide a new look at a plant pathogen and its presence in New England. Evidence points to the existence of ergot in Massachusetts and the appearance of convulsive ergotism symptoms in Elizabeth “Betty” Parris and Abigail Williams suggests that they had initially suffered from ergot poisoning. In order for ergot to be involved at all in this historical event it must first be placed at the scene of the crime, and for the fungus to be present it must first have a host to live on. Ergot is caused by one of the ascomycete fungi, or sac fungi, called Claviceps purpurea.