Utilization of Bone Scan and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography on Amputation Planning in Acute Microvascular Injury: Two Cases T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies

agronomy Review Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies Sofia Agriopoulou Department of Food Science and Technology, University of the Peloponnese, Antikalamos, 24100 Kalamata, Greece; [email protected]; Tel.: +30-27210-45271 Abstract: Ergot alkaloids (EAs) are a group of mycotoxins that are mainly produced from the plant pathogen Claviceps. Claviceps purpurea is one of the most important species, being a major producer of EAs that infect more than 400 species of monocotyledonous plants. Rye, barley, wheat, millet, oats, and triticale are the main crops affected by EAs, with rye having the highest rates of fungal infection. The 12 major EAs are ergometrine (Em), ergotamine (Et), ergocristine (Ecr), ergokryptine (Ekr), ergosine (Es), and ergocornine (Eco) and their epimers ergotaminine (Etn), egometrinine (Emn), egocristinine (Ecrn), ergokryptinine (Ekrn), ergocroninine (Econ), and ergosinine (Esn). Given that many food products are based on cereals (such as bread, pasta, cookies, baby food, and confectionery), the surveillance of these toxic substances is imperative. Although acute mycotoxicosis by EAs is rare, EAs remain a source of concern for human and animal health as food contamination by EAs has recently increased. Environmental conditions, such as low temperatures and humid weather before and during flowering, influence contamination agricultural products by EAs, contributing to the Citation: Agriopoulou, S. Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and appearance of outbreak after the consumption of contaminated products. The present work aims to Cereal-Derived Food Products: present the recent advances in the occurrence of EAs in some food products with emphasis mainly Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, on grains and grain-based products, as well as their toxicity and control strategies. -

The Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances

The Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances Draft Guidelines and Reference Material for Public Health Services To be used to assist in a pilot study from July – December 2001 April 2001 Jeff Fowles, Ph.D. Prepared by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, Limited Under contract by the New Zealand Ministry of Health DISCLAIMER This report or document ("the Report") is given by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited ("ESR") solely for the benefit of the Ministry of Health, Public Health Service Providers and other Third Party Beneficiaries as defined in the Contract between ESR and the Ministry of Health, and is strictly subject to the conditions laid out in that Contract. Neither ESR nor any of its employees makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for use of the Report or its contents by any other person or organisation. Guidelines for the Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances April 2001 Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Dr Michael Bates and Melissa Perks (ESR), Sally Gilbert and Helen Saba (Ministry of Health), Dr Donald Campbell (Midcentral Health), Dr Deborah Read (ERMANZ), and Dr Nerida Smith (National Poisons Centre) for useful contributions and helpful suggestions on the construction of these guidelines. Guidelines for the Notification of Injuries from Hazardous Substances April 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................1 -

Hallucinogens: a Cause of Convulsive Ergot Psychoses

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 6-1976 Hallucinogens: a Cause of Convulsive Ergot Psychoses Sylvia Dahl Winters Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Psychiatry Commons Recommended Citation Winters, Sylvia Dahl, "Hallucinogens: a Cause of Convulsive Ergot Psychoses" (1976). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 976. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/976 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT HALLUCINOGENS: A CAUSE OF CONVULSIVE ERGOT PSYCHOSES By Sylvia Dahl Winters Ergotism with vasoconstriction and gangrene has been reported through the centuries. Less well publicized are the cases of psychoses associated with convulsive ergotism. Lysergic acid amide a powerful hallucinogen having one.-tenth the hallucinogenic activity of LSD-25 is produced by natural sources. This article attempts to show that convulsive ergot psychoses are mixed psychoses caused by lysergic acid amide or similar hallucinogens combined with nervous system -

615.9Barref.Pdf

INDEX Abortifacient, abortifacients bees, wasps, and ants ginkgo, 492 aconite, 737 epinephrine, 963 ginseng, 500 barbados nut, 829 blister beetles goldenseal blister beetles, 972 cantharidin, 974 berberine, 506 blue cohosh, 395 buckeye hawthorn, 512 camphor, 407, 408 ~-escin, 884 hypericum extract, 602-603 cantharides, 974 calamus inky cap and coprine toxicity cantharidin, 974 ~-asarone, 405 coprine, 295 colocynth, 443 camphor, 409-411 ethanol, 296 common oleander, 847, 850 cascara, 416-417 isoxazole-containing mushrooms dogbane, 849-850 catechols, 682 and pantherina syndrome, mistletoe, 794 castor bean 298-302 nutmeg, 67 ricin, 719, 721 jequirity bean and abrin, oduvan, 755 colchicine, 694-896, 698 730-731 pennyroyal, 563-565 clostridium perfringens, 115 jellyfish, 1088 pine thistle, 515 comfrey and other pyrrolizidine Jimsonweed and other belladonna rue, 579 containing plants alkaloids, 779, 781 slangkop, Burke's, red, Transvaal, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, 453 jin bu huan and 857 cyanogenic foods tetrahydropalmatine, 519 tansy, 614 amygdalin, 48 kaffir lily turpentine, 667 cyanogenic glycosides, 45 lycorine,711 yarrow, 624-625 prunasin, 48 kava, 528 yellow bird-of-paradise, 749 daffodils and other emetic bulbs Laetrile", 763 yellow oleander, 854 galanthamine, 704 lavender, 534 yew, 899 dogbane family and cardenolides licorice Abrin,729-731 common oleander, 849 glycyrrhetinic acid, 540 camphor yellow oleander, 855-856 limonene, 639 cinnamomin, 409 domoic acid, 214 rna huang ricin, 409, 723, 730 ephedra alkaloids, 547 ephedra alkaloids, 548 Absorption, xvii erythrosine, 29 ephedrine, 547, 549 aloe vera, 380 garlic mayapple amatoxin-containing mushrooms S-allyl cysteine, 473 podophyllotoxin, 789 amatoxin poisoning, 273-275, gastrointestinal viruses milk thistle 279 viral gastroenteritis, 205 silibinin, 555 aspartame, 24 ginger, 485 mistletoe, 793 Medical Toxicology ofNatural Substances, by Donald G. -

Question of the Day Archives: Monday, December 5, 2016 Question: Calcium Oxalate Is a Widespread Toxin Found in Many Species of Plants

Question Of the Day Archives: Monday, December 5, 2016 Question: Calcium oxalate is a widespread toxin found in many species of plants. What is the needle shaped crystal containing calcium oxalate called and what is the compilation of these structures known as? Answer: The needle shaped plant-based crystals containing calcium oxalate are known as raphides. A compilation of raphides forms the structure known as an idioblast. (Lim CS et al. Atlas of select poisonous plants and mushrooms. 2016 Disease-a-Month 62(3):37-66) Friday, December 2, 2016 Question: Which oral chelating agent has been reported to cause transient increases in plasma ALT activity in some patients as well as rare instances of mucocutaneous skin reactions? Answer: Orally administered dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) has been reported to cause transient increases in ALT activity as well as rare instances of mucocutaneous skin reactions. (Bradberry S et al. Use of oral dimercaptosuccinic acid (succimer) in adult patients with inorganic lead poisoning. 2009 Q J Med 102:721-732) Thursday, December 1, 2016 Question: What is Clioquinol and why was it withdrawn from the market during the 1970s? Answer: According to the cited reference, “Between the 1950s and 1970s Clioquinol was used to treat and prevent intestinal parasitic disease [intestinal amebiasis].” “In the early 1970s Clioquinol was withdrawn from the market as an oral agent due to an association with sub-acute myelo-optic neuropathy (SMON) in Japanese patients. SMON is a syndrome that involves sensory and motor disturbances in the lower limbs as well as visual changes that are due to symmetrical demyelination of the lateral and posterior funiculi of the spinal cord, optic nerve, and peripheral nerves. -

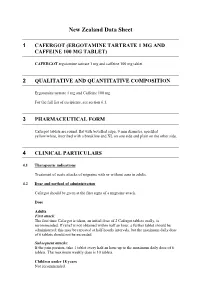

New Zealand Data Sheet

New Zealand Data Sheet 1 CAFERGOT (ERGOTAMINE TARTRATE 1 MG AND CAFFEINE 100 MG TABLET) CAFERGOT ergotamine tartrate 1 mg and caffeine 100 mg tablet 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Ergotamine tartrate 1 mg and Caffeine 100 mg For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Cafergot tablets are round, flat with bevelled edge, 9 mm diameter, speckled yellow/white, inscribed with a breakline and XL on one side and plain on the other side. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Treatment of acute attacks of migraine with or without aura in adults. 4.2 Dose and method of administration Cafergot should be given at the first signs of a migraine attack. Dose Adults First attack: The first time Cafergot is taken, an initial dose of 2 Cafergot tablets orally, is recommended. If relief is not obtained within half an hour, a further tablet should be administered; this may be repeated at half-hourly intervals, but the maximum daily dose of 6 tablets should not be exceeded. Subsequent attacks: If the pain persists, take 1 tablet every half an hour up to the maximum daily dose of 6 tablets. The maximum weekly dose is 10 tablets. Children under 18 years Not recommended. Maximum dose per attack or per day Adults: 6 mg ergotamine tartrate = 6 tablets. Maximum weekly dose Adults: 10 mg ergotamine tartrate = 10 tablets. Special populations Renal impairment Cafergot is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (see Contraindications). Hepatic impairment Cafergot is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment (see Contraindications). -

Role of the Intensive Care Unit in the Management of the Poisoned Patient Per Kulling and Hans Persson Swedish Poison Information Centre, Stockholm

Concepts in Toxicology Review Medical Toxicology I: 375·386 (1986) 0112·5966/0090·0375/$06.00/0 © ADIS Press Limited All rights reserved. Role of the Intensive Care Unit in the Management of the Poisoned Patient Per Kulling and Hans Persson Swedish Poison Information Centre, Stockholm Summary By applying a sensible toxicological approach to the general principles ofintensive care, an optimum setting for the treatment ofpoisoning is created. The intensive care unit (ICU) can perform the necessary close observation and monitoring, and thus facilitate rapid detection ofsymptoms, and the institution of early appropriate treatment. Diagnosis may be complex in poisoning and require continuous qualified interpretation of clinical and analytical data. Antidote therapy and treatment to enhance elimination ofthe poison must often be dealt with under careful supervision. The capacity ofthe ICU to counteract various toxic effects in a nonspecific way and to provide optimum symptomatic and supportive care is crucial. However, the ongoing toxic effects on the body must always be considered and allowed to guide symptomatic treatment. Thus, clinical toxicology appears to be a specialised branch of intensive care medicine. Many patients exposed to a poison may, after is of utmost importance for a proper interpretation initial measures like clinical assessment, gastric of clinical and analytical data and an immediate lavage and administration of activated charcoal, be start for necessary therapy. In some cases the ICU managed in general wards. However, to be able to may have a laboratory of its own, offering rapid adequately treat a severely poisoned patient the fa and frequent analysis. Another important aspect of cilities of an intensive care unit (ICU) are often the ICU is that there is generally a low threshold required and the capacity of such units to provide for accepting and utilising new and advanced ther optimum conditions for diagnosis and treatment apeutic methods. -

Ergotism and Other Mycotoxicoses in Ancient Mesopotamia?

Ergotism and Other Mycotoxicoses in Ancient Mesopotamia? Robert D. Biggs The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago It is well known that the synthetic hallucinogen LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) is derived from ergot, a fungus that grows on a variety of grasses. While the synthetic form is a relatively recent formula- tion and has inspired a scholarly literature of its own, the effect of ergot in human health has also been studied extensi vely in recent years I. When ingested in sufficient quantities, ergot produces a disease called ergotism which, in serious cases, has two variants, gangrenous and convulsive'. The designation "convul- sive" does not refer to true convulsions when consciousness is lost. The symptoms of convulsive ergotism include tingling in the fingers, crawling sensations on the skin, headaches, vertigo, muscle spasms leading to epileptic type convulsions, confusion, delusions, hallucinations, vomiting, and diarrhea", In connection with some of these manifestations, it is worth mentioning that there has been a serious suggestion that 4 ergotism was a major factor in the infamous Salem witchcraft affair of 1691 and 1692 • It has also been implicated in fa grande peur in France in 17895• We are all familiar with a number of fungi, which include mushrooms, molds, and mildews. We are also aware of the toxicity of some, especially mushrooms, but nevertheless a number of people each year are poisoned because they make a bad choice of which mushrooms to eat. Mushrooms, of course, are very visible fungi about which a great deal is published and about which many people consider themselves knowledgeable. -

Toxic Effects of Mycotoxins in Humans M

Research Toxic effects of mycotoxins in humans M. Peraica,1 B. RadicÂ,2 A. LucicÂ,3 & M. Pavlovic 4 Mycotoxicoses are diseases caused by mycotoxins, i.e. secondary metabolites of moulds. Although they occur more frequently in areas with a hot and humid climate, favourable for the growth of moulds, they can also be found in temperate zones. Exposure to mycotoxins is mostly by ingestion, but also occurs by the dermal and inhalation routes. Mycotoxicoses often remain unrecognized by medical professionals, except when large numbers of people are involved. The present article reviews outbreaks of mycotoxicoses where the mycotoxic etiology of the disease is supported by mycotoxin analysis or identification of mycotoxin-producing fungi. Epidemiological, clinical and histological findings (when available) in outbreaks of mycotoxicoses resulting from exposure to aflatoxins, ergot, trichothecenes, ochratoxins, 3-nitropropionic acid, zearalenone and fumonisins are discussed. Voir page 763 le reÂsume en francËais. En la pa gina 763 figura un resumen en espanÄ ol. Introduction baking of bread made with ergot-contaminated wheat, as well as to other ergot toxins and Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites of moulds that hallucinogens, as well as belladonna alkaloids from exert toxic effects on animals and humans. The toxic mandragora apple, which was used to treat ergotism effect of mycotoxins on animal and human health is (3). While ergotism no longer has such important referred to as mycotoxicosis, the severity of which implications for public health, recent reports indicate depends on the toxicity of the mycotoxin, the extent that outbreaks of human mycotoxicoses are still of exposure, age and nutritional status of the possible (4). -

Rudys List of Archaic Medical Terms.Xlsm

Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms A Glossary of Archaic Medical Terms, Diseases and Causes of Death. The Genealogist's Resource for Interpreting Causes of Death. Section 1 English Archaic Medical Terms Section 2 German / English Glossary Section 3 International / English Glossary www.antiquusmorbus.com Copying and printing is allowed for personal use only. Distribution or publishing of any kind is strictly prohibited. © 2005-2008 Antiquus Morbus, All Rights Reserved. This page left intentionally blank Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms A Glossary of Archaic Medical Terms, Diseases and Causes of Death. The Genealogist's Resource for Interpreting Causes of Death. Section 1 English Archaic Medical Terms Section 2 German / English Glossary Section 3 International / English Glossary www.antiquusmorbus.com Copying and printing is allowed for personal use only. Distribution or publishing of any kind is strictly prohibited. © 2005-2008 Antiquus Morbus, All Rights Reserved. This page left intentionally blank Table of Contents Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 EnglishGerman International Part 2 PAGE Part 4 PAGE Part 6 PAGE English A 5 German A 123 Croatian 153 English B 10 German B 124 Czech 154 English C 14 German C 127 Danish 155 English D 25 German D 127 Dutch 157 English E 29 German E 128 Finnish 159 English F 32 German F 129 French 161 English G 34 German G 130 Greek 166 English H 38 German H 131 Hungarian 167 English I 41 German I 133 Icelandic 169 English J 44 German J 133 Irish 170 English K 45 German K 133 Italian 170 English L 46 German -

PHR 250 5/2/07, 6,7P FUNGI and MYCOTOXINS Mehrdad Tajkarimi Materials from Michael E

PHR 250 5/2/07, 6,7p FUNGI AND MYCOTOXINS Mehrdad Tajkarimi Materials from Michael E. Mount Introduction: Mycotoxin is a toxin which is formed during fungus growth. “Myco” means mold and “toxin” represents poison. These toxins are mainly low molecular weight proteins produced by mushrooms and molds. Under proper environmental conditions (temperature, moisture, oxygen …), mycotoxin levels become high. Mycotoxins are generally of no known use to the fungi that produce them. Some mycotoxins have lethaleffects; some cause specific diseases or health problems; some of them affect on the immune system; some act as allergens or irritants; and some have no known effect on human and animal health. Some mycotoxins act on other micro-organisms, such as penicillin’s antibiotic action.Toxins tend to be processed by the liver for elimination via the kidneys. Some toxins are metabolically activated in the liver, rather than detoxified. Chronic exposures to mycotoxins often damage the liver, the kidneys or both. History: Mycotoxin problems such as ergotism and mushrom poisoning have been recognized for centuries. An outbreak occurred in the UK in 1960, in which 100,000 turkeys died of an unknown disease. The cause of death was identified as aflatoxin-contaminated peanut meal. Alimentary toxic aleukia (ATA), with more than 5000 deaths caused by trichothecene mycotoxins in grain in the USSR late in World War II, was one of the well- documented reports of mycotoxicosis. In last four decades, several mycotoxins and their sources have been discovered. Some of these are effective in animal feed or food, and sometimes both, and the effects of some of them on human and animal health has been proven. -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle.