The Ambulance, the Squad Car, and the Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ambulance the Squad Car & the Internet.Pdf

The Ambulance, the Squad Car, & the Internet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Susan P. Crawford, The Ambulance, the Squad Car, & the Internet, 21 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 873 (2006). Published Version http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/btlj/vol21/iss2/5/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12956284 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Berkeley Technology Law Journal Volume 21 | Issue 2 Article 5 March 2006 The Ambulance, the Squad Car, & the Internet Susan P. Crawford Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/btlj Recommended Citation Susan P. Crawford, The Ambulance, the Squad Car, & the Internet, 21 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 873 (2006). Available at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/btlj/vol21/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals and Related Materials at Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Berkeley Technology Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AMBULANCE, THE SQUAD CAR, & THE INTERNET By Susan P. Crawfordt TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN T R OD U C T IO N ............................................................................................ 874 II. THE MARKET CONTEXT ........................................................................... 877 III. FCC INTERNET SOCIAL POLICIES ...................................................... -

2015 Valuation Handbook – Guide to Cost of Capital and Data Published Therein in Connection with Their Internal Business Operations

Market Results Through #DBDLADQ 2014 201 Valuation Handbook Guide to Cost of Capital Industry Risk Premia Company List Cover image: Duff & Phelps Cover design: Tim Harms Copyright © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748- 6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. The forgoing does not preclude End-users from using the 2015 Valuation Handbook – Guide to Cost of Capital and data published therein in connection with their internal business operations. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

List of Section 13F Securities

List of Section 13F Securities 1st Quarter FY 2004 Copyright (c) 2004 American Bankers Association. CUSIP Numbers and descriptions are used with permission by Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No redistribution without permission from Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau. Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the CUSIP Numbers and standard descriptions included herein and neither the American Bankers Association nor Standard & Poor's CUSIP Service Bureau shall be responsible for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of the use of such information. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission OFFICIAL LIST OF SECTION 13(f) SECURITIES USER INFORMATION SHEET General This list of “Section 13(f) securities” as defined by Rule 13f-1(c) [17 CFR 240.13f-1(c)] is made available to the public pursuant to Section13 (f) (3) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [15 USC 78m(f) (3)]. It is made available for use in the preparation of reports filed with the Securities and Exhange Commission pursuant to Rule 13f-1 [17 CFR 240.13f-1] under Section 13(f) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. An updated list is published on a quarterly basis. This list is current as of March 15, 2004, and may be relied on by institutional investment managers filing Form 13F reports for the calendar quarter ending March 31, 2004. Institutional investment managers should report holdings--number of shares and fair market value--as of the last day of the calendar quarter as required by Section 13(f)(1) and Rule 13f-1 thereunder. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended December 31, 1999 ------------------- Check here if Amendment: / /; Amendment Number: ______ This Amendment (Check only one.): / / is a restatement. / / adds new holdings entries. Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: U.S. Bancorp ------------ Address: 601 Second Avenue South ----------------------- Minneapolis, MN 55402-4302 -------------------------- Form 13F File Number: 28- 551 --- The institutional investment manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed hereby represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Merita D. Schollmeier --------------------- Title: Vice President -------------- Phone: 651-205-2030 ------------ Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Merita D. Schollmeier St. Paul, MN 2/11/00 - ------------------------- ------------ ------- Information contained on the attached Schedule 13(f) is provided solely to comply with the requirements of Section 13(f) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Regulations promulgated thereunder. It is the position of U.S. Bancorp, that for any purpose other than Schedule 13-F, it is not an institutional investment manager and does not, in fact, exercise investment discretion with regard to any securities held in a fiduciary or agency capacity by any subsidiary or trust company. Report Type (Check only one.): /X/ 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check here if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) / / 13F NOTICE. -

6709BWOL Webstock

RIDING THE WEB-STOCK ROLLER COASTER Reprinted from the August 12, 2004 issue of BusinessWeek Online. Copyright © 2004 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. This reprint implies no endorsement, either tacit or expressed, of any company, product, service or investment opportunity. RIDING THE WEB-STOCK ROLLER COASTER Our BW Web 20 Index tracks a selection of favorite Net stocks, and this column will help interpret the ups and downs he past month has been rotten Just last week, Forrester Research christening the BW Web 20 Index Tfor Internet investors. Stocks raised its e-commerce forecast, pre- – is intended to help aggressive have been hammered since second- dicting U.S. online sales of $227 bil- investors accept the risk inherent in quarter earnings showed Web out- lion in 2007, up from earlier projec- the Web, but balance it by focusing fits growing pretty much as they had tions of $204 billion. Forrester on “real” companies with solid prod- promised – a change from their habit expects e-commerce in the U.S. to ucts, services, and profits. Every of slightly besting quarterly projec- grow 14% annually through 2010 – month, this column will do more than tions. The carnage has been just as three to four times faster than the track how stocks in our index trade – severe in the Real World Internet economy. Meanwhile, growth in it also will help investors figure out Index, a group of Web stocks we Europe is predicted to average 33% which rallies are sustainable and spot picked in 2002 to help ordinary annually through 2009. the bubblicious behavior that earned investors play the Internet without Net investing a bad rap. -

The Internet and the Web T6 a Technical View of System Analysis and Design

Technology Guides T1 Hardware T2 Software T3 Data and Databases T4 Telecommunications ᮣ T5 The Internet and the Web T6 A Technical View of System Analysis and Design Technology Guide The Internet 5 and the Web T5.1 What Is the Internet? T5.2 Basic Characteristics and Capabilities of the Internet T5.3 Browsing and the World Wide Web T5.4 Communication Tools for the Internet T5.5 Other Internet Tools T5.1 T5.2 Technology Guide The Internet and the Web T5.1 What Is the Internet?1 The Internet (“the Net”) is a network that connects hundreds of thousands of inter- nal organizational computer networks worldwide. Examples of internal organiza- tional computer networks are a university computer system, the computer system of a corporation such as IBM or McDonald’s, a hospital computer system, or a system used by a small business across the street from you. Participating computer systems, called nodes, include PCs, local area networks, database(s), and mainframes.A node may include several networks of an organization, possibly connected by a wide area network. The Internet connects to hundreds of thousands of computer networks in more than 200 countries so that people can access data in other organizations, and can communicate and collaborate around the globe, quickly and inexpensively. Thus, the Internet has become a necessity in the conduct of modern business. The Internet grew out of an experimental project of the Advanced Research Proj- BRIEF HISTORY ect Agency (ARPA) of the U.S. Department of Defense.The project was initiated in 1969 as ARPAnet to test the feasibility of a wide area computer network over which researchers, educators, military personnel, and government agencies could share data, exchange messages, and transfer files. -

Digitalización Es Futuro

ESPECIAL 2021 Digitalización es Futuro Un documento de referencia, desde el que podrá conocer opiniones, casos de éxito y más de 130 socios tecnológicos especializados en tecnologías para acelerar la digitalización y securización de su empresa. © Asociación @aslan, 2021 Primera edición “Especial 2021. Digitalización es Futuro”: marzo 2021 Producido por la Asociación @aslan con el apoyo de: Redacción: Tecno Media Comunicación Diseño y maquetación: Crealia Desarrollos de Comunicación. Tecnología y cambios de paradigma en el inicio de la nueva década Especial 2021 “Digitalización es Futuro” Tendencias, opiniones, casos de éxito y más de 130 socios tecnológicos Comienza una nueva década en la que la experiencia en digitalización y el talento de los profesionales especializados en las TIC son activos intangibles decisivos para la recuperación de nuestra economía y la resiliencia del tejido productivo. La Asociación @aslan agrupa y representa a este sector estratégico. Con más de 130 empresa asociadas y un ecosistema de 73.500 profesionales, abarca desde la innovación tecnológica internacional hasta los equipos que están liderando la transformación digital en sectores clave de la economía y las administraciones públicas. Patrocinadores del Especial 2021 Índice Prólogos Institucionales ......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 La Asociación, Comisiones y Grupos de Expertos ........................................................................................................ -

Fox Interactive Media Ranks #1 in Page Views; Yahoo! Sites Attract the Most Unique Visitors Comscore Media Metrix Releases November Top 50 Web Rankings and Analysis

Fox Interactive Media Ranks #1 in Page Views; Yahoo! Sites Attract the Most Unique Visitors comScore Media Metrix Releases November Top 50 Web Rankings and Analysis RESTON, VA, December 19, 2006 - comScore Media Metrix today released its monthly analysis of U.S. consumer activity at top online properties and categories for November. Fox Interactive Media topped all properties with 39.5 billion page views in November, primarily driven by the 38.7 billion pages consumed at MySpace.com, based on traffic from home, work and university locations. While Fox Interactive Media supplanted Yahoo! Sites as the top Web property by page views in November, Yahoo! Sites retained the top spot in audience size with 129.9 million unique visitors. Further, Yahoo's increased integration of AJAX technology may have had a dampening effect on page views, as the technology enables real-time site updates without the need to refresh a page. An additional comScore analysis released this week highlighted the importance of including home, work and university audiences in measuring the Web's largest properties. In fact, if university usage is omitted, the comparison of page views at Fox Interactive Media and Yahoo! Sites tells a very different story: Yahoo! Sites, with 35.6 billion page views for November, would rank higher than Fox Interactive Media with 34.9 billion. "Inclusion of online activity occurring at university locations is critical to producing accurate online audience measurements," said Jack Flanagan, executive vice president of comScore Media Metrix. "The market was understandably perplexed by reports that offered seemingly conflicting opinions on whether Fox Interactive or Yahoo! had actually captured the top ranking in terms of page views." "The difference lies in whether the online activity of college students, which represents nearly 15 million people, is included in the measurements - a critically important detail when measuring activity at MySpace.com, which is included in the Fox Interactive property," Flanagan added. -

Online Selling & Ecrm August 2002

Online Selling & eCRM August 2002 www.emarketer.com This report is the property of eMarketer, Inc. and is protected under both the United States Copyright Act and by contract. Section 106 of the Copyright Act gives copyright owners the exclusive rights of reproduction, adaptation, publication, performance and display of protected works. Accordingly, any use, copying, distribution, modification, or republishing of this report beyond that expressly permitted by your license agreement is prohibited. Violations of the Copyright Act can be both civilly and criminally prosecuted and eMarketer will take all steps necessary to protect its rights under both the Copyright Act and your contract. If you are outside of the United States: copyrighted United States works, including the attached report, are protected under international treaties. Additionally, by contract, you have agreed to be bound by United States law. Online Selling & eCRM Table of Contents 3 Methodology 5 The eMarketer Difference 6 The Benefits of eMarketer’s Aggregation Approach 7 “Benchmarking” and Projections 7 I Introduction 9 A. Estimating the Number of Commercial Websites 10 B. Estimating the Number of Website Visitors 15 C. The Growing Importance of the Internet Channel 20 II B2C Websites 23 A. Website Capabilities 24 Website Budgeting and ROI 26 E-Commerce and General Website Capabilities 35 Managing Website Traffic 43 B. Consumer Preferences 51 III B2B Websites 65 A. Website Capabilities 66 B. User Preferences 81 IV Online Customer Service & eCRM 87 A. Website Capabilities 88 B. User Preferences 105 Index of Charts 117 3 ©2002 eMarketer, Inc. Reproduction of information sourced as eMarketer is prohibited without prior, written permission. -

Why the Survivors Survived: Examining The

WHY THE SURVIVORS SURVIVED: EXAMINING THE CHARACTERISTICS OF ONLINE COMPANIES DURING THE DOT-COM ERA By Peyton Elizabeth Purcell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of Finance Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 7, 2018 ii WHY THE SURVIVORS SURVIVED: EXAMINING THE CHARACTERISTICS OF ONLINE COMPANIES DURING THE DOT-COM ERA Project Approved: Supervising Professor: Dr. Paul Irvine, Ph.D. Department of Finance Cheryl Carithers, M.A. Department of English iii ABSTRACT This paper examines the dot-com bubble and the characteristics that enabled certain online companies to survive the crash in March of 2000. The purpose of the study was to examine financial data to understand what enabled certain companies to survive the dot- com bubble, while other companies with seemingly similar characteristics did not. The past few years sparked debate amongst investors on whether or not another bubble formed among technology companies such as Facebook, Amazon, Tesla, and Netflix. Currently, the world is in the middle of a technology boom. Investors care about the future success of technology companies that have a lot of promise baked into their stock price. My thesis attempts to examine the dot-com bubble that “burst” in March of 2000 and the companies that were able to withstand the crash until 2005. My results reveal a few conclusions about the companies in the dot-com era including (1) companies with negative earnings had a lower chance of survival; (2) companies with “.com” had a lower chance of survival; (3) companies with more volatile stock prices had a lower chance of survival; (4) companies that had higher advertising expenses had a lower chance of survival; (5) companies with higher shares outstanding had a higher chance of survival and; and (6) companies with pure online operations had a lower chance of survival. -

Sun IBM Walmart Blockbuster Circuitcity Gateway SBC

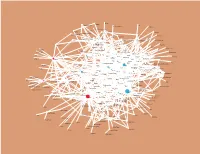

Netopia Tellabs JuniperNetworks GE NetworkSolutions Citibank GeneralInstrument Lumeta Fujitsu CheckPoint Siemens SonusNetworks Juno CharlesSchwab NetZero Harbinger GM Broadcom Alcatel NetworkAssociates Lucent BofA ComputerAssociates MicroStrategy Tibco CommerceOne Netegrity Ericsson AmEx GlobalCrossing ALLTEL Verizon VeriSign PwC UPS MapInfo Lawson RIM RSA AnswerThink KMart NortelNetworks 3COM i2 CheckFree MasterCard Verity VISA BaltimoreTechnologies Handspring AvantGo Macromedia SAP CareerMosaic Livelink Nokia ATG Motorola Palm CIBER JDEdwards MP3.com BT Unisys Interwoven Staples Qualcomm Yahoo! Ariba Veritas EMC Oracle Peoplesoft Sun FoundryNetworks EDS Ford Sprint DeloitteToucheTohmatsu divine WebMethods Drugstore Adobe IBM E.piphany iPlanet HP Siebel BMCSoftware CSC bowstreet Borders Agency.com Vodafone Cisco Amazon Novell Intel AT&T Kana ExodusComm WebTrends BroadVision ToysRUs Monster KPNQwest Vignette InfoSpace CDNow Nextel D&B CacheFlow METAGroup Accenture BEASystems Apple Interliant Participate.com AP Sony NewsCorp Kodak Loudcloud C|Net SoftBank KPMG SAS GartnerGroup TARGET EarthLink Fidelity Compaq RedHat RealNetworks BankOne Universal Dell moreover.com ForresterResearch OfficeMax C&W CNN Travelocity XOComm. RadioShack AberdeenGroup E*Trade VerticalNet AltaVista CircuitCity Audible Akamai MSFT McAfee WebMD Inktomi Cablevision Samsung SportsLine InterNap QXL.com CVS MediaOne theStreet AOL WalMart BestBuy Buy.com Teleglobe CMGI NBC Starbucks Gateway CapGemini BellSouth RoadRunner AskJeeves DigitalIsland Blockbuster CBS Excite TerraLycos PivotalSoftware Intuit NTT Slate ViacomCBS Genuity SBC Comcast LookSmart LibertyMedia Spyglass eLance IDT Disney/ABC BellCanada B&N NaviSite AAdvantage EMI DoubleClick Net2Phone eBay Prodigy Netcentives Kinko's LiquidAudio MapQuest Bertelsmann Oxygen MercuryInteractive WellsFargo Level3 AutoTrader Sears CareerBuilder napster USATODAY Pajek. -

Access, Demographics & Usage, February 2002

North America Online: Access, Demographics & Usage February 2002 www.emarketer.com This report is the property of eMarketer, Inc. and is protected under both the United States Copyright Act and by contract. Section 106 of the Copyright Act gives copyright owners the exclusive rights of reproduction, adaptation, publication, performance and display of protected works. Accordingly, any use, copying, distribution, modification, or republishing of this report beyond that expressly permitted by your license agreement is prohibited. Violations of the Copyright Act can be both civilly and criminally prosecuted and eMarketer will take all steps necessary to protect its rights under both the Copyright Act and your contract. If you are outside of the United States: copyrighted United States works, including the attached report, are protected under international treaties. Additionally, by contract, you have agreed to be bound by United States law. North America Online Table of Contents 3 Methodology 7 The eMarketer Difference 8 The Benefits of eMarketer’s Aggregation Approach 9 “Benchmarking” and Future-Based Projections 9 I Introduction 11 A. Key Findings - Then and Now 13 II Internet Users 17 A. Worldwide Internet Users 20 B. Internet Users in the US 22 C. Who is Not Online and Why? 28 III Internet Households 35 A. Comparative Estimates: Online Households in the US 38 B. Households Online by Technology 40 Broadband Users 55 Satellite 60 Fixed Wireless 61 IV Internet Access Devices: PC, TV and Mobile Devices 63 A. PCs 66 B. TV 71 C. Mobile Phones & PDAs 73 V Online Demographics 77 A. Gender 82 B. Age 90 C.