The Writing on the Screen: Images of Text in the German Cinema from 1920 to 1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

Textual Analysis Film: Do the Right Thing (1989) Director: Spike Lee Sequence Running Time: 00:50:55 - 00:55:55 Word Count: 1745

Student sample Textual Analysis Film: Do The Right Thing (1989) Director: Spike Lee Sequence Running Time: 00:50:55 - 00:55:55 Word Count: 1745 In this paper I will analyze an extract from Spike Lee's Do The Right Thing (1989) that reflects the political, geographical, social, and economical situations through Lee's stylistic use of cinematography, mise-en-scene, editing, and sound to communicate the dynamics of the characters in the cultural melting pot that is Bedford-Stuyvesant,Brooklyn in New York City. This extract manifests Lee's artistic visions that are prevalent in the film and are contemplative of Lee's personal experience of growing up in Brooklyn. "This evenhandedness that is at the center of Spike Lee's work" (Ebert) is evident through Lee's techniques and the equal attention given to the residents of this neighborhood to present a social realism cinema. Released almost thirty years ago, Lee's film continues to empower the need for social change today with the Black Lives Matter movement and was even called "'culturally significant'by the U.S. Library of Congress" (History). Do The Right Thing takes place during the late 1980s in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn and unravels the "bigotry and violence" (Lee) in the neighborhood of a single summer day, specifically one of the hottest of the season. Being extremely socially conscious, Do The Right Thing illustrates the dangers of racism against African Americans and was motivated by injusticesof the time--especially in New York--such as the death of Yusef Hawkins and the Howard Beach racial incident. -

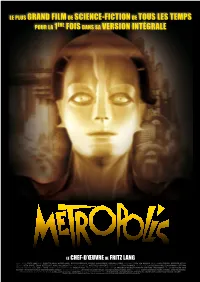

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI)

Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) The Department of English RAJA N.L. KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Midnapore, West Bengal Course material- 2 on Techniques of Cinematography (Some other techniques) A close-up from Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) For SEC (English Hons.) Semester- IV Paper- SEC 2 (Film Studies) Prepared by SUPROMIT MAITI Faculty, Department of English, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College (Autonomous) Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. April, 2020. 1 Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) Techniques of Cinematography (Film Studies- Unit II: Part 2) Dolly shot Dolly shot uses a camera dolly, which is a small cart with wheels attached to it. The camera and the operator can mount the dolly and access a smooth horizontal or vertical movement while filming a scene, minimizing any possibility of visual shaking. During the execution of dolly shots, the camera is either moved towards the subject while the film is rolling, or away from the subject while filming. This process is usually referred to as ‘dollying in’ or ‘dollying out’. Establishing shot An establishing shot from Death in Venice (1971) by Luchino Visconti Establishing shots are generally shots that are used to relate the characters or individuals in the narrative to the situation, while contextualizing his presence in the scene. It is generally the shot that begins a scene, which shoulders the responsibility of conveying to the audience crucial impressions about the scene. Generally a very long and wide angle shot, establishing shot clearly displays the surroundings where the actions in the Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. -

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya* May 10, 2014 How far can the media protect or undermine democratic institutions in unconsolidated democracies, and how persuasive can they be in ensuring public support for dictator’s policies? We study this question in the context of Germany between 1929 and 1939. Radio slowed down the growth of political support for the Nazis, when Weimar government introduced pro-government political news in 1929, denying access to the radio for the Nazis up till January 1933. This effect was reversed in 5 weeks after the transfer of control over the radio to the Nazis following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. After full consolidation of power, radio propaganda helped the Nazis to enroll new party members and encouraged denunciations of Jews and other open expressions of anti-Semitism. The effect of Nazi radio propaganda varied depending on the listeners’ predispositions toward the message. Nazi radio was most effective in places where anti-Semitism was historically high and had a negative effect on the support for Nazi messages in places with historically low anti-Semitism. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! * Maja Adena is from Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Ruben Enikolopov is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School, Moscow. Maria Petrova is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School. Veronica Santarosa is from the Law School of the University of Michigan. Ekaterina Zhuravskaya is from Paris School of Economics (EHESS) and the New Economic School. -

1 Veit Harlan and Jud Süß – Conrad Veidt and Jew Süss Veit Harlan And

1 Veit Harlan and Jud Süß – Conrad Veidt and Jew Süss Veit Harlan and Conrad Veidt were both associated with the flowering of German stage and cinema in the Weimar Republic. Veidt, born in 1893, was already a major figure, starring in productions like The Cabinet of Dr.Caligari that made cinema history. Harlan, seven years younger, was beginning to make a name for himself on the stage. When Hitler came to power their paths diverged diametrically. Harlan was an opportunist, made his peace with the regime and acquired a reputation as a director of films. Later he and his second wife, Hilde Körber, became friends of Goebbels. In April 1933 Conrad Veidt, who had just married his Jewish third wife, Lily Prager, left Germany after accepting the role of the German Commandant in the British film I was a Spy . When he returned to Germany the Nazis detained him to stop him taking the lead role in the projected British Jew Süss film. He eventually got out, but his acceptance of the role made the breach with his native country irrevocable. Six years later Harlan was persuaded by Goebbels to take on the direction of Jud Süß , the most notorious but also one of the most successful of the films made under the auspices of the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. Kristina Söderbaum, then his wife, took the female lead. In the meantime Conrad Veidt had moved to Hollywood and in 1942 appeared as Major Strasser, the German officer, in Casablanca , a role for which he is probably best known in the Anglo-Saxon world. -

Výmarská Ústava 1919

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Právnická fakulta Katedra teorie práva a právních dějin Milan Cigánek Výmarská ústava 1919 Diplomová práce Vedoucí diplomové práce: Mgr. Jana Janišová, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2010 1 Já, níţe podepsaný Milan Cigánek, autor diplomové práce na téma „Výmarská ústava 1919“, která je literárním dílem ve smyslu zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským, dávám tímto jako subjekt údajů svůj souhlas ve smyslu § 4 písm. e) zákona č. 101/2000 Sb., správci: Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Kříţkovského 8, Olomouc, 771 47, Česká Republika ke zpracování osobních údajů v rozsahu: jméno a příjmení v informačním systému, a to včetně zařazení do katalogů, a dále ke zpřístupnění jména a příjmení v informačních systémech Univerzity Palackého, a to včetně zpřístupnění pomocí metod dálkového přístupu. Údaje mohou být takto zpřístupněny uţivatelům sluţeb Univerzity Palackého. Realizaci zpřístupnění zajišťuje ke dni tohoto prohlášení patřičná vnitřní sloţka Univerzity Palackého, Knihovna UP. Souhlas se poskytuje na dobu ochrany autorského díla dle zákona č. 121/2000 Sb. *** Prohlašuji tímto, ţe moje osobní údaje výše uvedené jsou pravdivé. Prohlašuji, ţe jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně a uvedl v ní veškerou literaturu a ostatní informační zdroje, které jsem pouţil. V Němčanech dne 28. 2. 2010 Milan Cigánek 2 Poděkování Rád bych touto cestou vyjádřil své upřímné poděkování za cenné připomínky, ochotu, pomoc a spolupráci vedoucí mé diplomové práce, paní Mgr. Janě Janišové, Ph.D. 3 Obsah 1. Úvod 7 1.1. Metodologie 8 1.2. Diskuse pramenů a literatury 9 2. Kontury vývoje Německa po prohrané válce 13 2.1. Předrevoluční tání 13 2.2. -

Listado Campeones

Note Definition English Spanish Categoría AATROX Champion Name Aatrox Aatrox Armadura AATROX Champion Skin Justicar Aatrox Aatrox Justiciero Armadura AATROX Champion Skin Mecha Aatrox Aatrox Mecha Armadura AATROX Champion Skin Sea Hunter Aatrox Aatrox Cazador Marino Traje AHRI Champion Name Ahri Ahri Traje AHRI Champion Skin Dynasty Ahri Ahri Dinástica Traje AHRI Champion Skin Popstar Ahri Ahri Estrella del Pop Traje AHRI Champion Skin Midnight Ahri Ahri de Medianoche Traje AHRI Champion Skin Foxfire Ahri Ahri Raposa de Fuego Traje AHRI Champion Skin Challenger Ahri Ahri Retadora Traje AHRI Champion Skin Academy Ahri Ahri Academia Traje AHRI Champion Skin Arcade Ahri Ahri de Arcadia Traje AKALI Champion Name Akali Akali Traje AKALI Champion Skin Stinger Akali Akali Aguijón Traje AKALI Champion Skin Crimson Akali Akali Carmesí Traje AKALI Champion Skin All-star Akali Akali Supercampeona Traje AKALI Champion Skin Nurse Akali Enfermera Akali Traje AKALI Champion Skin Blood Moon Akali Akali Luna de Sangre Traje AKALI Champion Skin Silverfang Akali Akali Colmillo de Plata Traje AKALI Champion Skin Headhunter Akali Akali Cazadora de Cabezas Armadura AKALI Champion Skin Sashimi Akali Akali Sashimi Traje ALISTAR Champion Name Alistar Alistar Traje ALISTAR Champion Skin Black Alistar Alistar Negro Traje ALISTAR Champion Skin Golden Alistar Alistar Dorado Traje ALISTAR Champion Skin Matador Alistar Alistar Matador Traje ALISTAR Champion Skin Longhorn Alistar Alistar Cuernoslargos Traje ALISTAR Champion Skin Unchained Alistar Alistar Desencadenado -

Extracting Wartime Memory from Contemporary Politics

Maja Zehfuss. Wounds of Memory: The Politics of War in Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. xv + 294 pp. $95.40, cloth, ISBN 978-0-521-87333-8. Reviewed by Kimberly Redding Published on H-German (September, 2009) Commissioned by Susan R. Boettcher In a thought-provoking appraisal of contem‐ Chapters 1 and 2 outline the basic premise of porary German politics, twentieth-century litera‐ the book: namely, that even as politicians invoke ture, and postmodernist theory, political scientist personal memories to establish expertise and Maja Zehfuss challenges the validity of using col‐ claim authority, academics assert memory's mal‐ lective memory to defend contemporary political leability, often demonstrating that memories re‐ decisions and positions. Given what scholars veal more about present contexts than any specif‐ know about memory construction, she argues, ic historical event or experience. Zehfuss uses politicians' tendency to justify contemporary poli‐ Günter Grass's novel Im Krebsgang (2002) to cies through references to World War II-era expe‐ demonstrate how memories are perpetually rein‐ riences are fundamentally fawed. Drawing exam‐ vented as individuals negotiate--and renegotiate-- ples from both political speeches and postwar lit‐ relationships between past, present, and future. erature, she illustrates the fragility of memory In political debates, she argues, contemporary and the malleability of remembered narratives. tensions dominate; politicians' need to use the While novelists can accommodate multiple mem‐ past, usually to justify positions, sharply colors ories in their fctional narratives, politicians--and their narratives of that past. Novelists, on the oth‐ their audiences--often confuse personal memories er hand, make relatively few demands on their with authoritative knowledge of the past. -

The Importance of the Weimar Film Industry Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: Christian P

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Tamara Dawn Goesch for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Foreign Languages and Litera- tures (German), Business, and History presented on August 12, 1981 Title: A Critique of the Secondary Literature on Weimar Film; The Importance of the Weimar Film Industry Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Christian P. Stehr Only when all aspects of the German film industry of the 1920's have been fully analyzed and understood will "Weimar film" be truly comprehensible. Once this has been achieved the study of this phenomenon will fulfill its po- tential and provide accurate insights into the Weimar era. Ambitious psychoanalytic studies of Weimar film as well as general filmographies are useful sources on Wei- mar film, but the accessible works are also incomplete and even misleading. Theories about Weimar culture, about the group mind of Weimar, have been expounded, for example, which are based on limited rather than exhaustive studies of Weimar film. Yet these have nonetheless dominated the literature because no counter theories have been put forth. Both the deficiencies of the secondary literature and the nature of the topic under study--the film media--neces- sitate that attention be focused on the films themselves if the mysteries of the Weimar screenare to be untangled and accurately analyzed. Unfortunately the remnants of Weimar film available today are not perfectsources of information and not even firsthand accounts in othersour- ces on content and quality are reliable. However, these sources--the films and firsthand accounts of them--remain to be fully explored. They must be fully explored if the study of Weimar film is ever to advance. -

Occidental Regionalism in the Nibelungenlied: Medieval Paradigms of Foreignness

OCCIDENTAL REGIONALISM IN THE NIBELUNGENLIED: MEDIEVAL PARADIGMS OF FOREIGNNESS BY SHAWN ROBIN BOYD DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor C. Stephen Jaeger, Chair Professor Marianne Kalinke Associate Professor Frederick Schwink Associate Professor Laurie Johnson Associate Professor Carol Symes ii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the issue of foreignness in the Nibelungenlied, raising questions about the nature, and crossing, of intra-Christian borders within the text that separate customs, practices, and worldviews. It analyzes cultural alterity and its attendant outcomes in the first half of the Nibelungenlied using concepts from anthropology and cultural and sociological theory. The dissertation argues that multiple levels of foreignness, as defined by the philosopher Bernd Waldenfels, separate characters in the Nibelungenlied. Despite their varying origins, these instances of alienation all have a common result: a lack of a complete picture of the world for individual characters and the prevention of close human connections that would allow intentions and motivations to be divined. Characters’ imperfect understandings of their surroundings are fostered by their foreignness and drive many of the conflicts in the text, including Siegfried’s verbal clash with the Burgundians when he first arrives in Worms, Brünhild’s entanglement with Gunther and Siegfried, and the argument between Kriemhild and Brünhild. In addition, this dissertation argues that the constant interaction with the foreign undergone by the court at Worms leads to a change in its culture away from one which sees appearance and reality as one and the same to one that takes advantage of the power granted by a newfound ability to separate Sein from Schein.