Global Food Needs Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Fertility Differentials in Liberia and Ghana Using Multilevel

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON An Analysis of Fertility Differentials in Liberia and Ghana Using Multilevel Models. By Nicholas John Parr Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Statistics, Faculty of Social Sciences April 1992 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL STATISTICS Doctor of Philosophy AN ANALYSIS OF FERTILITY DIFFERENTIALS IN LIBERIA AND GHANA USING MULTILEVEL MODELS by Nicholas John Parr This thesis investigates differentials in the levels of fertility, nuptiality and contraceptive use in Liberia and Ghana, using data from the recent Demographic and Health Surveys in these countries. Of particular interest is the effect of the community in which a woman lives on her current and past fertility, her marital status and her use of contraception. This interest stems from the fact that, although the community in which a woman lives is integral to anthropological explanations of fertility, statistical models of fertility have rarely included an assessment of community effects. -

Year 1, Quarter 3 Progress Report (To June 2014)

ENGINEERING SERVICES FOR RURAL ROADS REHABILITATION (ES3R) CONTRACT NO: EDH-I-00-08-00023 YEAR 1, QUARTER 3 PROGRESS REPORT (TO JUNE 2014) 20 July 2014 The views expressed in this publication do not necessarilyES3R reflect Quarter the vlyiews Report of the to United June States2014 Agency for International Development1 or the US Government. ENGINEERING SERVICES FOR RURAL ROAD REHABILITATION (ES3R) CONTRACT NO. EDH-I-00-08-00023 YEAR 1, QUARTER 3 PROGRESS REPORT (TO JUNE 2014) Prepared for: USAID/Liberia Prepared by: Howard M Shelmerdine Jim Clarke Michael Kpange 20 July 2014 The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. This report was prepared for the U.S. Agency for International Development. It was prepared by CDM International, Engineering Services Rural Roads Rehabilitation (ES3R) ES3R Quarterly Report to June 2014 2 Acronyms A & E Architect and Engineer BoQ Bills of Quantity COP Chief of Party COR Contracting Officer Representative ES3R Engineering Services for Rural Roads Rehabilitation ETL Engineering Team Leader FED Food and Enterprise Development FTF Feed the Future FTL Field Team Leader F2M Farm to Market F2MRR Farm to Market Road Rehabilitation GIS Geographic Information System GOL Government of Liberia LESSP Liberia Energy Sector Support Project LMWP Liberia Municipal Water Project MOF Ministry of Finance MPEA Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs MPW Ministry of Public Works OCA Organizational Capacity Assessment PIRS Performance Indicator Results Sheet RE Resident Engineer SI Site Inspector USAID United States Agency for International Development ES3R Quarterly Report to June 2014 3 ENGINEERING SERVICES FOR RURAL ROADS REHABILITATION (ES3R) YEAR 1, QUARTER 3, APRIL TO JUNE 2014 LIST OF CONTENTS 1. -

Human Rights Issues Emanating from Traditional Practices in Liberia

UNMIL UNITED NATIONS MISSION IN LIBERIA An Assessment of Human Rights Issues Emanating from Traditional Practices in Liberia Table of Contents 1. Executive summary .................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 3. Methodology and constraints .................................................................................... 3 4. Overview of traditional and cultural societies and practices in Liberia ............... 4 5. Legal and policy framework related to traditional and cultural practices .......... 6 5.1. International and regional human rights framework ................................................. 6 5.2. Domestic legal and policy framework for the protection of human rights in the context of cultural practices ................................................................................................... 10 5.3. Challenges in the legal and normative framework .................................................... 13 5.3.1. The Hinterland Regulations ..................................................................................... 13 5.3.2. “Positive Culture” in Liberian law .......................................................................... 14 5.3.3. Perceptions of human rights among traditional actors and communities ................ 15 6. Human rights abuses emanating from cultural and traditional practices ......... 15 6.1. -

Advancing Youth Project: Labor Market Assessment Report

Advancing Youth Project Labor Market Assessment — Liberia This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development, USAID/Liberia Cooperative Agreement No. 669-A-11-00001 to Education Development Center. The content and opinions expressed within do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Advancing Youth Project: Labor Market Assessment i Acknowledgements The Labor Market Assessment (LMA) team hereby conveys thanks to the Government of Liberia and the Ministry of Education for the establishment of Alternative Basic Education program targeting unschooled youth. We would also like to express our appreciation to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) for funding the Advancing Youth project. Special thanks to Mrs. Mardea Nyumah, of USAID in Monrovia for providing technical guidance and advice throughout the design and review process of the LMA. We are also grateful to Mr. S. Tornorlah Varpilah, the Minister of Youth and Sports for his contribution of time and information which formed an important part of this report. To the many traders and companies who were interviewed during the survey, farmers and traders who participated in value chain analysis and key informants from private sector, NGOs and government institutions, to all we owe you many thanks. The USAID/Advancing Youth team including partner organizations, Education Development Center (EDC), Mercy Corps and YMCA led by Chief of Party, Simon James, was instrumental in providing valuable administrative support and team coordination. To all team coordinators, thanks for the tireless effort. YMCA played a crucial role by providing competent youth assessors, who worked hard to design data collection tools, administered the assessment in the five counties and finalized data entry process smoothly. -

NOTES on SETTLEMENT HISTORIES of GBELAY-GEH STATUTORY DISTRICT, NIMBA COUNTY, LIBERIA

NOTES ON SETTLEMENT HISTORIES OF GBELAY-GEH STATUTORY DISTRICT, NIMBA COUNTY, LIBERIA [Maarten Bedert in collaboration with Freeman B. Bartuah] HALLE (SAALE) 2017 MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY DEPartment ‘IntegraTION AND CONFLICt’ FIELD NOTES AND RESEARCH PROJECTS XVII MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY DEPARTMent ‘IntegraTION AND CONFLICT’ FIELD NOTES AND RESEARCH PROJECTS XVII Notes on Settlement Histories of Gbelay-Geh Statutory District, Nimba County, Liberia Published by Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle (Saale) P. O. Box 11 03 51 D - 06017 Halle /Saale (Germany) 9270 2׀0345׀Phone 49 http://www.eth.mpg.de ISSN 2193-987X Author: Maarten Bedert (in collaboration with Freeman B. Bartuah) Assisted by: Viktoria Zeng and Robert Dobslaw Cover Photo: Window view, Karnplay (Liberia), 2012 © Martine Noordemeer Printed 2017 by Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle (Saale) © 2017 Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology TABLE OF CONTENTS Series Editor’s Preface ................................................................................ iv Introduction .................................................................................................. v PArt 1: GBELAY CHIEFDOM 1. Karnplay ................................................................................................... 1 2. Peelar ........................................................................................................ 6 3. Loelay .................................................................................................... -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE PRESS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Press and Public Affairs Office as at: Friday, 23 February 2007 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Special Court Indictee Sam Hinga Norman Dies in Dakar / Public Affairs Office Page 3 Prosecutor Expresses Regret at the Death of Sam Hinga Norman / Office of The Prosecutor Page 4 Government Statement On The Death Of Chief Sam Hingha Norman / Office of The President Page 5 Norman is Dead / For di People Page 6 Norman: Dead / Awoko Page 7 Norman’s Death is A Catastrophe for SLPP Government / African Champion Page 8 Hinga Norman Bled to Death [MORE] / Awareness Times Pages 9-14 Norman’s Death Shake Salone / New Citizen Pages 15-17 Special Court –Mismanagement of Information / New Citizen Page 18 Hinga Norman Dies in Dakar / The Spectator Page 19 “ I Won’t Come Back Alive”… / Concord Times Pages 20-21 Sagely Archives / Concord Times Pages 22-23 Norman, Sankoh, Maskita Dead [MORE] / The Exclusive Pages 24-29 How Special Court Broke the News of Hinga Norman’s Death / Independent Observer Pages 30-31 He is Dead [MORE] / The Spark Pages 32-33 Hinga Norman Dies in Dakar / Sierra News Page 34 Hinga Norman Drops Dead / The News Page 35 Vox Pop / The News Page 36 International News UN-backed Sierra Leone Court Says War Crimes Suspect’s Death Means Justice Denied / UN News Page 37 S Leone War Crimes Suspect Dies / BBC Online Page 38 Sierra Leone War Crimes Indictee Hinga Norman Dies / Reuters Pages 39-40 Sierra Leone War Crimes Defendant Dies / Associated Press Page 41 Sierra Leone War Crimes Suspect Dies in Custody / Voice of America Page 42 UN-backed Special Court Wants Hinga Norman's Death Investigated / Star Radio (Liberia) Page 43 Shock Waves Rip Through Diaspora and Sa. -

Nimba County Development Agenda

\ Nimba County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia Nimba County Development Agenda 2008 – 2012 bong County Vision Statement An Educated, United and Developed Nimba. An Educated Nimba All citizens of Nimba County will have access to education. A United Nimba All citizens of Nimba County respect shared values of peace, equal opportunity and ethnic, cultural and religious freedoms. A Developed Nimba All citizens of Nimba County desire sustained economic growth, access to basic services and improved infrastructure. Republic of Liberia Prepared by the County Development Committee, in collaboration with the Ministries of Planning and Economic Affairs and Internal Affairs. Supported by the UN County Support Team project, funded by the Swedish Government and UNDP. Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS........! iii FOREWORD..........................................................................! iv PREFACE!!............................................................................. vi NIMBA COUNTY OFFICIALS..................................................! vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................! ix PART ONE - INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1.!Introduction................................................................................................! 1 1.2.!History........................................................................................................! 1 1.3.!Geography..................................................................................................! -

Sinoe CDA Draft

Sinoe County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia Sineo County Development Agenda 2008 – 2012 bong County Vision Statement Sinoe will be a national leader in development and innovation; a County where citizens enjoy food security and have access to basic social services and modern infrastructure, where good governance and rule of law prevail. Core Values The County will endeavor to build on our core competencies and values to support: Accessibility to equal opportunities for all citizens and residents of Sinoe County ; That peace, security and the rule of law be restored and preserved; Governance based upon transparency and effectiveness; Sustained economic growth, the creation of jobs; and Preserving the natural resources and also protecting the environment. Republic of Liberia Prepared by the County Development Committee, in collaboration with the Ministries of Planning and Economic Affairs and Internal Affairs. Supported by the UN County Support Team project, funded by the Swedish Government and UNDP. Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS........! iii FOREWORD..........................................................................! iv PREFACE!!............................................................................. vi SINOE COUNTY OFFICIALS...................................................! vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................! ix PART ONE - INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1.!Introduction................................................................................................! -

Assessment of FARA 1.0 Outcomes on the Capacity of MOH and Chts, and the Quality of Service Provision at Health Facilities in Liberia

Assessment of FARA 1.0 Outcomes on the Capacity of MOH and CHTs, and the Quality of Service Provision at Health Facilities in Liberia April 25, 2017 This document was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by InterMedia under the Liberia Strategic Analysis activity under contract AID-669-C-16-00002. DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Table of Contents List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................ 3 List of Figures and Tables.............................................................................................................................. 3 Map of Liberia and Evaluated Facilities ......................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Key Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................................... 6 Theme 1 – FARA 1.0 Impact ............................................................................................................... -

Text Begins Here

SECRETARIAT - 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland - TEL: +41 22 791 6033 - FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www.actalliance.org Appeal Liberia Emergency Assistance to Ivorian Refugees in Liberia, Revision 1 - LBR111 Appeal Target: US$ 2,429,558 Balance Requested: US$1,210,472 Geneva, 17 May 2011 Dear Colleagues, For more than five months now, the political crisis in Ivory Coast has led to more than 173,000 Ivorians to cross the border to Liberia as refugees. After increased violence, the situation started to escalate in the end of February, and since then, there has been a continuous flow of refugees which at the writing of this revised appeal has not stopped despite the capture of Mr Gbagbo and the calm in Abidjan, the Ivorian financial capital. According to the latest estimations there are about 173,000 Ivorian refugees in Liberia – up from the 70,000 Ivorians when the original Appeal was issued. This is causing a humanitarian crisis affecting both the refugees and the receiving host communities. Ivory Coast was mired in a political stalemate since the results of the national elections of 28th November 2010 were declared. The incumbent president, Laurent Gbagbo, declined to concede defeat to the apparent winner, Alassane Ouattara, citing rigging in the Northern region of the country where Ouattara has a wide following. Fighting in various parts of Ivory Coast (including Abidjan, and the Western areas close to Liberian border) followed, leaving more than 1,500 people dead and an estimated 800,000 internally displaced. With the assistance of French troops, Gbagbo was finally captured in Abidjan on 11 April. -

1848 Ministries and Agencies in Liberia Name

Ministries and Agencies in Liberia Ministry of Foreign Affairs Creation: 1848 Name: Its current, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, came into being in 1972 Former Name: Department of State (DoS). The DoS was headed, initially, by a Secretary of State. Hilary Teague, who also drafted the Liberian Declaration of Independence, became Liberia’s first secretary of State in 1848. Current Function: It implements Liberia’s external policies and relations and manages its Diplomatic missions accredited abroad. Former Function: Same as the new function Order of Succession: 3. The Minister of Foreign Affairs is the dean of the cabinet and therefore ascends to the presidency after the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the Pro Tempore of the Liberian Senate. Employees: Outlays: Ministry of Finance & Development Planning Creation: 2014 Name: Ministry of Finance & Development Planning Former Name: Ministry of Finance Function: MFDP formulates and administers economic development, fiscal and tax policies for the promotion of sound and efficient management of the financial resources of the Government, administers the revenue program of the Government, including supervision of the collection of the revenues; reports the financial activities and financial position of the Government to the President and the Legislature; maintains the central accounting records of the Government and prescribe for all Government agencies of accounts reporting and documentation necessary to safeguard the assets of the Government. MFDP also formulates fiscal policies for -

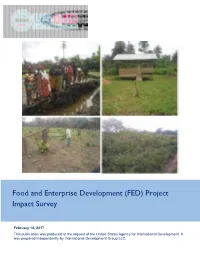

Food and Enterprise Development (FED) Project Impact Survey

Food and Enterprise Development (FED) Project Impact Survey February 14, 2017 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by International Development Group LLC. FOOD AND ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT (FED) PROJECT IMPACT SURVEY LEARNING EVALUATION AND ANALYSIS PROJECT-II (LEAP-II) ACTIVITY ORDER #25: Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-12-00042/AID-OAA-TO-14-00046 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Photo credits: Richard Rousseau. Clockwise from upper left: Lowland rice beneficiary group, goat shelter, cassava field, newly planted vegetable field. The Evaluation Team included: Richard Rousseau (Team Leader), Nicholai Lidow (Senior Analyst/ Statistician), Tamara Glazer (Research Analyst), Hyosun Bae (Research Analyst), Daniel Mwero (Senior Field Survey Specialist), Emmanuel Nimbuen (Agriculture Economist), Alice Perkins (Field Survey Specialist), Joseph Duawo (CAPI Specialist), Dexter Merchant (CAPI Specialist), Alvin Teezoe (CAPI Specialist), Dickerson Williams (CAPI Specialist), and Mohammed Sheriff (Finance/Operations Manager). International Development Group LLC (IDG) worked in collaboration with African Development Associates (ADEAS) – a Liberian organization to manage and implement the Impact Survey. TABLE OF CONTENTS Evaluation Purpose .....................................................................................................................................................