Food and Enterprise Development (FED) Project Impact Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soups & Stews Cookbook

SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK *RECIPE LIST ONLY* ©Food Fare https://deborahotoole.com/FoodFare/ Please Note: This free document includes only a listing of all recipes contained in the Soups & Stews Cookbook. SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare COMPLETE RECIPE INDEX Aash Rechte (Iranian Winter Noodle Soup) Adas Bsbaanegh (Lebanese Lentil & Spinach Soup) Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Almond Soup Artichoke & Mussel Bisque Artichoke Soup Artsoppa (Swedish Yellow Pea Soup) Avgolemono (Greek Egg-Lemon Soup) Bapalo (Omani Fish Soup) Bean & Bacon Soup Bizar a'Shuwa (Omani Spice Mix for Shurba) Blabarssoppa (Swedish Blueberry Soup) Broccoli & Mushroom Chowder Butternut-Squash Soup Cawl (Welsh Soup) Cawl Bara Lawr (Welsh Laver Soup) Cawl Mamgu (Welsh Leek Soup) Chicken & Vegetable Pasta Soup Chicken Broth Chicken Soup Chicken Soup with Kreplach (Jewish Chicken Soup with Dumplings) Chorba bil Matisha (Algerian Tomato Soup) Chrzan (Polish Beef & Horseradish Soup) Clam Chowder with Toasted Oyster Crackers Coffee Soup (Basque Sopa Kafea) Corn Chowder Cream of Celery Soup Cream of Fiddlehead Soup (Canada) Cream of Tomato Soup Creamy Asparagus Soup Creamy Cauliflower Soup Czerwony Barszcz (Polish Beet Soup; Borsch) Dashi (Japanese Kelp Stock) Dumpling Mushroom Soup Fah-Fah (Soupe Djiboutienne) Fasolada (Greek Bean Soup) Fisk och Paprikasoppa (Swedish Fish & Bell Pepper Soup) Frijoles en Charra (Mexican Bean Soup) Garlic-Potato Soup (Vegetarian) Garlic Soup Gazpacho (Spanish Cold Tomato & Vegetable Soup) 2 SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food -

Global Seafood Cookbook *Recipe List Only*

GLOBAL SEAFOOD COOKBOOK *RECIPE LIST ONLY* ©Food Fare https://deborahotoole.com/FoodFare/ Please Note: This free document includes only a listing of all recipes contained in the Global Seafood Cookbook. GLOBAL SEAFOOD COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare COMPLETE RECIPE INDEX Appetizers & Salads Almejas a la Marinera (Spanish Clams in Marinara Sauce) Atherina (Greek Fried Smelts) Bara Lawr (Welsh Laver Bread) Blackbeard's Crab Cakes Clams Casino Codfish Balls Crab & Artichoke Dip Cracker Pirate Smear (Crab & Shrimp Dip) Easy Sushi Rolls Eggs Drumkilbo (eggs with lobster & shrimp) Fried Calamari (Squid) Gefilte Fish (Jewish Stuffed Fish) Herring Dip (Jewish) Hot Lobster Dip Inlagd Sill (Swedish Salted Herring) Lobster Salad Maine Clam Dip Marinated Anchovies (Basque) Old Bay Crab Cakes Oysters on the Half Shell Oysters Rockefeller Popcorn Shrimp Prawn Crackers Salade Basque (Basque Salad with Tuna) Salata Mishwiyya (Tunisian Grilled Pepper, Tomato & Tuna Salad) Salmagundi (Pirate Grand Salad) Selyodka Pod Shouboi (Russian Herring Salad) Shenanchie's Clam Dip Shenanchie's Sushi (Avocado & Shrimp) Shrimp Puffs Shrimp Salad Shrimpy Devils (deviled eggs with shrimp) Sledz w Smietanie (Polish Creamed Herring) Steamed Mussels Sushi Rice Taramasalata (Greek Fish Roe Dip) Tempura (Japanese Seafood & Vegetables) Tomates Monegasque (Monegasque Tomatoes with Tuna) Tuna Rice Cakes Uncle Pat's Crab Cocktail 2 GLOBAL SEAFOOD COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare Entrees & Sides Almondine Sole Apelsinfisk (Swedish Orange Fish) Baked Mahi-Mahi Bar a la Monegasque -

APPETIZERS Caribbean Fish Soup 13 Conch Fritters 17 Soup Du Jour

APPETIZERS Caribbean Fish Soup 13 Conch Fritters 17 Soup Du Jour 12 Fish Fingers 12 Tossed Salad 11 Shrimp Cocktail 20 Chicken Wings 10 Tortilla Chips & Salsa 10 SALAD PLATTERS Light Luncher 22 Serenity Salad Special 22 {Soup du Jour w/Tossed {Caesar salad with grilled Salad and Fresh Dinner Rolls} chicken breast} w/Grilled Fish 27 w/Grilled Shrimp 29 FRESH SEAFOOD Fresh Fish Sandwich 20 {Grilled on a bun with sautéed onion; served with lettuce, tomato & french fries} Fish Tacos 20 {Grilled fish, mango salsa, shredded purple cabbage, & tartar sauce, served with french fries} Fresh Grouper/Snapper Fillet or Whole 29 {Pan-seared, grilled, or steamed} Fresh Caught Lobster/Crayfish Market Price {Grilled and served with drawn butter, lemon, garlic, & tarragon} Grilled Shrimp Skewers 35 {Served with pineapples, peppers, and zucchini – Choice of BBQ or Lemon Butter Garlic sauce} Beer Batter Shrimp 35 {Shrimp dipped in a beer batter and deep-fried and served w/tartar sauce} POULTRY Jumbo Leg {Deep fried or grilled} 14 All served with french fries or rice, lettuce & tomato or cole slaw BEEF CHARBROILED Strip Steak {10 oz} 35 Cooked to order & served with french fries or rice, lettuce & tomato or cole slaw Cheese Burger {Swiss or American} 16 Hamburger 14 All cooked to order & served with french fries Barbecue Ribs 18 {Rolled in Serene BBQ sauce & served with lettuce, tomato & french fries} PANINIS Club 17 Ham 13 Cheese 10 Ham & Cheese 14 Turkey 14 All served with french fries and cole slaw Side Orders 6 Rice du Jour French Fries Prices are quoted in US$ currency and a 15% Service Charge will be added . -

An Analysis of Fertility Differentials in Liberia and Ghana Using Multilevel

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON An Analysis of Fertility Differentials in Liberia and Ghana Using Multilevel Models. By Nicholas John Parr Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Statistics, Faculty of Social Sciences April 1992 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL STATISTICS Doctor of Philosophy AN ANALYSIS OF FERTILITY DIFFERENTIALS IN LIBERIA AND GHANA USING MULTILEVEL MODELS by Nicholas John Parr This thesis investigates differentials in the levels of fertility, nuptiality and contraceptive use in Liberia and Ghana, using data from the recent Demographic and Health Surveys in these countries. Of particular interest is the effect of the community in which a woman lives on her current and past fertility, her marital status and her use of contraception. This interest stems from the fact that, although the community in which a woman lives is integral to anthropological explanations of fertility, statistical models of fertility have rarely included an assessment of community effects. -

Global Food Needs Project

◙DAN .:: emergency needs assessment branch INDEPENDENT FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT IN LIBERIA Food security and nutrition survey in Lofa, Nimba, and Montserrado Counties June 2005 United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) Rome Independent Food Security Assessment in Liberia © 2005 United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) Via Cesare Giulio Viola 68/70, Parco de Medici, 00148, Rome, Italy Emergency Needs Assessment Branch (ODAN), Operation Department Chief: Wolfgang Herbinger Project Manager: Hirotsugu Aiga Tel: +39-06-6513-3276 Fax: +39-06-6513-3080 Email: [email protected] This study was funded by UK Department for International Development (DfID) ii Forewords There has been a growing demand for more accurate and evidence-based emergency needs assessments in recent years. World Food Programme (WFP), as one of the main channels for humanitarian assistance, responded to these calls by organizing several consultations with experts, partner agencies and donors to identify the areas for improvement and develop a strategy for strengthening its capacities in emergency needs assessments. WFP's Executive Board endorsed this strategy which involves the preparation of a Emergency Food Security Assessment (EFSA) handbook, research work on assessment methodologies, investment in improved food security information in selected disaster-prone countries and a stand-by capacity for "independent assessments". Establishing a capacity for "independent assessments" seeks to address existing shortcomings in three areas: (a) meeting assessment needs in countries without a WFP Country Office; (b) augmentation of assessment capacities in countries with limited WFP Country Office capacities; and (c) provision of an external perspective in countries where earlier assessments have been contested. The report presented here falls into the second category. -

Chef Ricchi's Cacciucco (Fish Soup)

Chef Ricchi’s Cacciucco (Fish Soup) Cacciucco is an ever-changing recipe based on what is available at the time. Some items are ALWAYS there: clams, mussels, tomatoes, white wine. But for the rest, feel free to improvise: add octopus, calamari, whatever you feel like adding. The important thing is that you follow a number of steps to develop the flavors. And this is how you do it. Ingredients 1 1/2 tbsp olive oil 2 cups of dry white wine (pinot grigio, verdicchio work 1 lb. mussels, clean, in the shell perfectly) 1 lb. clams (smallest you can find), clean, in the shell 4 tbsp of chopped parsley 8-10 large shrimps, with the shell, but deveined 2 peperoncini finely chopped (or chile de arbol, if it is easier to find for you- remember that chile de arbol is 12 oz. white fish, chopped in bite sized pieces: whatever hotter than peperoncino) you have: I often use tilapia, but you could use any inexpensive white fish 4 cloves of garlic, finely chopped 10-12 mini bay scallops (you can use normal scallops - 1 red onion, finely chopped 8/12 of them , or omit them) salt and pepper to taste 1/2 can of diced tomatoes 12 slices of baguette or ciabatta bread A handful of cherry tomatoes, cut in half How to make it 1. Heat the olive oil in pan large enough to contain all the fish and the broth that you will develop. I use cast iron be- cause it better conveys the heat to the food, but any large pan with a lid will do. -

Soup at the Distinguished Table in Mexico City, 1830-1920

SOUP AT THE DISTINGUISHED TABLE IN MEXICO CITY, 1830-1920 Nanosh Lucas A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2017 Committee: Amílcar Challú, Committee Co-Chair Franciso Cabanillas, Committee Co-Chair Amy Robinson Timothy Messer-Kruse © 2017 Nanosh Jacob Isadore Joshua Lucas All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Amílcar Challú, Committee Co-Chair Francisco Cabanillas, Committee Co-Chair This thesis uses soup discourse as a vehicle to explore dimensions of class and hierarchies of taste in Mexican cookbooks and newspapers from 1830-1920. It contrasts soups with classic European roots, such as sopa de pan (bread soup), with New World soups, such as sopa de tortilla (tortilla soup) and chilaquiles (toasted tortillas in a soupy sauce made from chiles). I adopt a multi-disciplinary approach, combining quantitative methods in the digital humanities with qualitative techniques in history and literature. To produce this analysis, I draw from Pierre Bourdieu’s work on distinction and social capital, Max Weber’s ideas about modernization and rationalization, and Charles Tilly’s notions of categorical inequality. Results demonstrate that soup plays a part in a complex drama of inclusion and exclusion as people socially construct themselves in print and culinary practice. Elites attempted to define respectable soups by what ingredients they used, and how they prepared, served, and consumed soup. Yet, at the same time, certain soups seemed to defy hierarchical categorization, and that is where this story begins. iv To Lisa and Isadora Lucas. Thank you for your sacrifices. -

Cooking Freshwater Fish WHY THIS BOOK?

&RRNLQJ)UHVKZDWHU)LVK A nutrition booklet with healthy and tasty recipes to improve fish consumption This booklet is one of the products of the Clean Fish Better Life campaign. Clean Fish Better Life An awareness creation initiative launched by &RRNLQJ)UHVKZDWHU)LVK The SmartFish project CREDITS Concept and structure: Davide Signa Text and Recipes: Mutindi Maithya Graphic: Alessandra Argenti Layout: Shirley Chan Technical supervision: Ansen Ward and Davide Signa Contributions from: Yvette DieiOuadi, Margareth Massete, Yahya Mgawe, John Ryder, Jogeir Toppe Photo credits: ©Alessandra Argenti/CVF, ©Davide Signa/FAO a production www.culturalvideo.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Why this book? .................................................................................................................................. 6 Why it is good to eat fish? ............................................................................................................... 8 Main freshwater fish .......................................................................................................................... 10 PRACTICAL TIPS How to ensure safe fish consumption ........................................................................................ 12 How to choose a fresh fish .............................................................................................................. 14 How to choose good quality processed fish ........................................................................... 16 How to clean fish well .................................................................................................................... -

Product List 2016.Pdf

Product List 2016 Marinated Chilled Seafood and Anchovies in plastic tubs page 1 Marinated and chilled Seafood and Anchovies page 2 Ambient products and Chilled Mediterranean Vegetables page 3 Chilled Fish, Seafood and Vegetable Terrines pages 4-5 Assorted Seafood and Vegetable Salads page 6 Speciality Products page 7 Fresh chilled sauces page 8 Fresh and long life Soups page 9 Chilled and ambient Rillettes, Beans and Meals page 10 All products are subject to availability Fresh chilled Seaweed page 11 Various pricing options are available please ask for details Chilled and ambient Seaweed products, Agar Agar page 12 The shelf-life shown is for guidance only. Our products usually Dried Seaweed, Seaweed Court Bouillon and Pasta page 13 carry a considerably longer shelf-life than the minimum shown Frozen and other Speciality Products page 14 Full Technical Support is available to all our customers www.meridian-sea.com e-mail: [email protected] Shelf Life Units per Product Code Unit Size (days) Case Marinated Seafood Squid Salad 1887 42 1 Kg 4 Octopus Salad 1870 42 1 Kg 6 Fruits de Mer (Seafood Salad) 1863 42 1 Kg 6 Seafood Salad for Pizza 1028 42 1 Kg 4 Sardine Fillets with Basil 1856 60 1 Kg 6 Marinated Anchovies 500g Anchovy Fillets Natural in Oil 1814 80 500g 8 Anchovy Fillets Oriental 1821 80 500g 8 Anchovy Fillets Natural in Oil 1814 80 500g 8 Marinated Anchovies 1 Kg Anchovy Fillets Natural in Oil 1818 80 1 Kg 8 Anchovy Fillets Oriental 1825 80 1 Kg 8 Anchovy Fillets and Garlic 1801 80 1 Kg 8 Anchovy Fillets Provencale 1832 80 -

View Dinner Menu

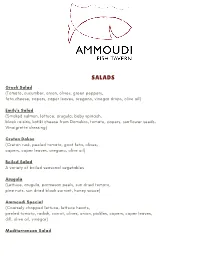

SALADS Greek Salad (Tomato, cucumber, onion, olives, green peppers, feta cheese, capers, caper leaves, oregano, vinegar drops, olive oil) Emily's Salad (Smoked salmon, lettuce, arugula, baby spinach, black raisins, katiki cheese from Domokos, tomato, capers, sunflower seeds, Vinaigrette dressing) Cretan Dakos (Cretan rusk, peeled tomato, goat feta, olives, capers, caper leaves, oregano, olive oil) Boiled Salad A variety of boiled seasonal vegetables Arugula (Lettuce, arugula, parmesan peels, sun dried tomato, pine nuts, sun dried black currant, honey sauce) Ammoudi Special (Coarsely chopped lettuce, lettuce hearts, peeled tomato, radish, carrot, olives, onion, pickles, capers, caper leaves, dill, olive oil, vinegar) Mediterranean Salad TRADITIONAL STARTERS Toasted Bread (olive oil, oregano and olives) Santorini's fried potatoes Spicy Cheese Salad (Goat feta with peppers) Tzatziki (Yoghurt, garlic, cucumber) Agioritiki Eggplant Salad (baked local flasks or white aubergines with garlic, onion and parsley, extra virgin olive oil) Fried Zucchini (Spiced fried zucchini with yoghurt sauce dip) Saganaki Cheese White Taramosalata (White tarama, onion, potato, fresh lemon juice, sunflower oil) Santorini's Fava (capers, onion and olive oil) Santorini's Tomato balls (Tomato, onion, garlic, parsley, flour) Santorini's Zucchini balls Grilled Halloumi (Grilled Cypriot cheese and tomato) Slice goat feta in crust leaf with honey and black/white sesame Mastelo with mastic, honey and sesame Variety of grilled vegetables (Fresh seasonal vegetables with -

Changes in Nutrient Profile and Antioxidant Activities of Different

molecules Article Changes in Nutrient Profile and Antioxidant Activities of Different Fish Soups, Before and After Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion Gaonan Zhang 1, Shujian Zheng 2, Yuqi Feng 2, Guo Shen 1, Shanbai Xiong 1,3 and Hongying Du 1,3,* 1 Key Laboratory of Environment Correlative Dietology, Ministry of Education, College of Food Science and Technology, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China; [email protected] (G.Z.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (S.X.) 2 Key Laboratory of Analytical Chemistry for Biology and Medicine of the Ministry of Education, Department of Chemistry, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430070, China; [email protected] (S.Z.); [email protected] (Y.F.) 3 National R & D Branch Center for Conventional Freshwater Fish Processing, Wuhan 430070, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-027-8728-3007 Academic Editor: Jolanta Kumirska Received: 4 July 2018; Accepted: 3 August 2018; Published: 6 August 2018 Abstract: Different kinds of freshwater fish soups show a diverse range of health functions, due to their different nutritional substances and corresponding bioactivities. In the current study, in order to learn the theoretical basis of the potential role fish soup plays in diet therapy functions, the changes of nutrient profiles and antioxidant activities in crucian carp soup and snakehead soup (before and after simulated gastrointestinal digestion) were investigated, such as chemical composition, free amino acids, mineral and fatty acid contents, DPPH radical scavenging activity, ferrous ion chelating activity, hydroxyl radical-scavenging activity and the reducing power effect. Results show that the content of mineral elements in snakehead fish soup was significantly higher than that of crucian carp soup, especially for the contents of Ca, Zn, Fe. -

Wedding Package 2021

JWMARRIOTT SURABAYA And so... the adventure begins with my whole heart for my whole life I BECAME YOURS & YOU BECAME MINE. A GOOD MARRIAGE ISN'T SOMETHING YOU FIND, IT'S SOMETHING YOU MAKE,AND YOU HAVE TO KEEP ON MAKING IT. Exquisite Luxurious Destination Weddings Offering the finest bespoke experiences, we extract our couple's true essence with custom planning, coordination, and consultation. With a meticulous eye for detail, we create an ambience of impeccable beauty and curate once-in-a lifetime sensory events. JWMARRIOTT SURABAYA Ballroom Floor Plan Reception Capacity: 1.500 person __Jv uv._ ___ __,vu "t_ / lh 111\ nl VJ 7) Ballroom A-C @16 Tables Royal Ballroom Inside 60 Tables Ballroom B @20 Tables Foyer 14 Tables Capacity: Area: Theatre Reception Dimensions (sq ft.) 1200 1500 (LxWxH) 7,922 46x24x7 ASEAN BUFFET MENU Blissful Package SOUP choose 1 (one) item APPETIZER choose 2 (two) items Braised asparagus and chicken soup ⚬ Braised asparagus and crab meat soup BBQ beef lemongrass salad ⚬ ⚬ Braised chicken and sweet corn soup Chicken salad with pineapple in curry sauce ⚬ ⚬ Braised fish maw and chicken soup Filipino Lumpia ⚬ ⚬ Braised seafood and mushroom soup Fresh Vietnamese salad rolls (Goi Guon) ⚬ ⚬ Braised tofu, seafood, and mushroom soup Mixed fruits salad with sweet mayonnaise ⚬ ⚬ Braised Szechuan spicy and sour soup Mussel Salad with barbeque sauce ⚬ ⚬ Tom yam talay (mix seafood) Pan-seared tuna salad with cucumber and mayonnaise ⚬ ⚬ Tom yam gong (prawn) Rice noodle, chicken with lime dressing ⚬ ⚬ Sesame – crusted tuna chunks