Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Frentes Del Anticomunismo. Las Derechas En

Los frentes del anticomunismo Las derechas en el Uruguay de los tempranos sesenta Magdalena Broquetas El fin de un modelo y las primeras repercusiones de la crisis Hacia mediados de los años cincuenta del siglo XX comenzó a revertirse la relativa prosperidad económica que Uruguay venía atravesando desde el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A partir de 1955 se hicieron evidentes las fracturas del modelo proteccionista y dirigista, ensayado por los gobiernos que se sucedieron desde mediados de la década de 1940. Los efectos de la crisis económica y del estancamiento productivo repercutieron en una sociedad que, en la última década, había alcanzado una mejora en las condiciones de vida y en el poder adquisitivo de parte de los sectores asalariados y las capas medias y había asistido a la consolidación de un nueva clase trabajadora con gran capacidad de movilización y poder de presión. El descontento social generalizado tuvo su expresión electoral en las elecciones nacionales de noviembre de 1958, en las que el sector herrerista del Partido Nacional, aliado a la Liga Federal de Acción Ruralista, obtuvo, por primera vez en el siglo XX, la mayoría de los sufragios. Con estos resultados se inauguraba el período de los “colegiados blancos” (1959-1966) en el que se produjeron cambios significativos en la conducción económica y en la concepción de las funciones del Estado. La apuesta a la liberalización de la economía inauguró una década que, en su primera mitad, se caracterizó por la profundización de la crisis económica, una intensa movilización social y la reconfiguración de alianzas en el mapa político partidario. -

Hugo Cores Former Guerrillas in Power:Advances, Setbacks And

Hugo Cores Former Guerrillas in Power: Advances, Setbacks and Contradictions in the Uruguayan Frente Amplio For over 135 years, Uruguayan politics was essen- tially a two party system. There had been other “small parties” including socialist parties, commu- nist parties or those inspired by Christian groups but all of them garnered little electoral support. Within the two principal political parties that competed for power, however, there were factions within each that could be considered to a greater or lesser extent progressive, anti-imperialist, and/or committed to some kind of vision of social justice. For the most part, the working class vote tended to gravitate towards these progressive wings within the domi- nant parties. The Twentieth Century history of the Uruguayan left would have been very distinct had pragmatism prevailed, an attitude that was later called the logic of incidencia by leaders of the Independent Batllist Faction (CBI – Corriente Batllista Independiente). Indeed, what sense did it make during the 1920s, 30s, 40s and 50s to be a socialist, communist, or Christian Democrat when if all taken together, they failed to reach even 10% of the vote? When the “theorists” of the CBI spoke of the “logic of incidencia, they referred to the idea that voting and cultivating an accumulation of left forces within the traditional political parties was a viable strategy to 222 • Hugo Cores have an organised impact upon the state apparatus, establishing positions of influence from within. The intent of the CBI itself to pursue such a strategy ultimately failed and disintegrated or became absorbed within the ranks of political support given to the Colorado Party of Sanguinetti.1 To remain outside of the traditional political parties, in contrast, meant that the opposition would be deprived of incidencia. -

Paraguay: in Brief Name Redacted Analyst in Latin American Affairs

Paraguay: In Brief name redacted Analyst in Latin American Affairs August 31, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44936 Paraguay: In Brief Summary Paraguay is a South American country wedged between Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil. It is about the size of California but has a population of less than 7 million. The country is known for its rather homogenous culture—a mix of Latin and Guarani influences, with 90% of the population speaking Guarani, a pre-Columbian language, in addition to Spanish. The Paraguayan economy is one of the most agriculturally dependent in the hemisphere and is largely shaped by the country’s production of cattle, soybeans, and other crops. In 2016, Paraguay grew by 4.1%; it is projected to sustain about 4.3% growth in 2017. Since his election in 2013, President Horacio Cartes of the long-dominant Colorado Party (also known as the Asociación Nacional Republicana [ANC]), has moved the country toward a more open economy, deepening private investment and increasing public-private partnerships to promote growth. Despite steady growth, Paraguay has a high degree of inequality and, although poverty levels have declined, rural poverty is severe and widespread. Following Paraguay’s 35-year military dictatorship in the 20th century (1954-1989), many citizens remain cautious about the nation’s democracy and fearful of a return of patronage and corruption. In March 2016, a legislative initiative to allow a referendum to reelect President Cartes (reelection is forbidden by the 1992 constitution) sparked large protests. Paraguayans rioted, and the parliament building in the capital city of Asunción was partially burned. -

LAS ANTIGUAS BANDERAS PROVINCIALES DE LA ARGENTINA (1815-1888) David Prando

Comunicaciones del Congreso Internacional de Vexilología XXI Vexilobaires 2005 LAS ANTIGUAS BANDERAS PROVINCIALES DE LA ARGENTINA (1815-1888) David Prando 1. La Liga Federal (1815-1820) El conflicto entre el centralismo de Buenos Aires y el autonomismo provincial - durante la guerra de la Independencia -, produjo la aparición de la Liga Federal, dirigida por el caudillo José Gervasio de Artigas. Su Liga estaba integrada por la Banda Oriental (provincia natal de Artigas), Santa Fé, Entre Ríos, Corrientes, Misiones y Córdoba. Santiago del Estero se plegó también al artiguismo, pero por brevísimo tiempo. Para distinguirse de Buenos Aires, Artigas ordenó a sus seguidores que izaran tricolores con el celeste y blanco porteños y el rojo federal. El resultado: una profusión de las tricolores más variadas. Y, debido a la interpretación de cada una de esas provincias, tuvo lugar el nacimiento de las banderas provinciales. Como en los cantones de la Confederación Suiza. Posiblemente, las enseñas cantonales inspiraron a los federales argentinos. En cambio, en los EE.UU. ningúno de los estados tenía pabellón propio, excepto las milicias locales. La Banda Oriental tuvo tres banderas: blanca, azul, colorada (1815-1816); azul, blanca, roja (1816-1820); y la última, como la segunda, pero con la leyenda “Libertad o Muerte”. Las primeras dos se usaron en la guerra civil contra Buenos Aires, y en la contra Portugal. Y la tercera fué la de los “33 Orientales” cuando la guerra argentino-brasileña (1825-1828). Santa Fé adoptó la tricolor de la Liga (azul-blanca-azul con una franja diagonal descendente colorada). Después, esa faja roja fué rosada (quizá para demostrar que Santa Fé había dejado al caudillo oriental. -

Los Tupamaros, Continuadores Históricos Del Ideario Artiguista

LOS TUPAMAROS CONTINUADORES HISTORICOS DEL IDEARIO ARTIGUISTA Melba Píriz y Cristina Dubra Considerado el territorio de la Banda Oriental como "tierra sin ningún provecho" por los conquistadores españoles, su conquista será tardía y este hecho signará la historia de esta fértil pradera, habitada desde ya mucho tiempo (estudios recientes nos llevan a considerar en miles de años la presencia de los primeros pobladores en la región) por comunidades indígenas en algunos casos cultivadores y, o cazadores, pescadores y recolectores .La situación de frontera interimperial (conflicto de límites entre los dominios de España y Portugal) determinará el interés por estos territorios pese a la sociedad indígena indómita que la habitaba. En el siglo XVII, la introducción del ganado bovino pautará de aquí en más la economía y la sociedad de esta Banda. La primera forma de explotación de la riqueza pecuaria fue la vaquería, expedición para matar ganado, extraer el cuero y el sebo. La vaquería depredó el ganado "cimarrón", por eso se irá sustituyendo este sistema por "la estancia", establecimiento permanente con ocupación de tierra. El poblamiento urbano fue también una consecuencia del carácter fronterizo de nuestro territorio. En 1680 los portugueses fundan la Colonia del Sacramento y a partir de 1724 los españoles fundan Montevideo. Durante el coloniaje estará presente un gran conflicto entre los grandes latifundistas por un lado y los pequeños y medianos hacendados por otro A comienzos del siglo XIX, se producen las invasiones inglesas al Río de la Plata. La ocupación que realizaron si bien breve, no dejará de tener importancia. Se agudizaron, por ejemplo, las contradicciones ya existentes en la sociedad colonial y comenzó a hacerse inminente la lucha por el poder entre una minoría española residente encabezada por los grandes comerciantes monopolistas y los dirigentes del grupo criollo, hijos de españoles nacidos en América. -

Artigas, O Federalismo E As Instruções Do Ano Xiii

1 ARTIGAS, O FEDERALISMO E AS INSTRUÇÕES DO ANO XIII MARIA MEDIANEIRA PADOIN* As disputas entre as tendências centralistas-unitárias e federalistas, manifestadas nas disputas políticas entre portenhos e o interior, ou ainda entre províncias-regiões, gerou prolongadas guerras civis que estendeu-se por todo o território do Vice-Reino. Tanto Assunção do Paraguai quanto a Banda Oriental serão exemplos deste enfrentamento, como palco de defesa de propostas políticas federalistas. Porém, devemos ressaltar que tais tendências apresentavam divisões internas, conforme a maneira de interpretar ideologicamente seus objetivos, ou a forma pelo qual alcançá-los, ou seja haviam disputas de poder internamente em cada grupo, como nos chama a atenção José Carlos Chiaramonte (1997:216) : ...entre los partidarios del Estado centralizado y los de la unión confederal , pues exsiten evidencias de que en uno y en outro bando había posiciones distintas respecto de la naturaleza de la sociedad y del poder, derivadas del choque de concepciones historicamente divergentes, que aunque remetían a la común tradicón jusnaturalista que hemos comentado, sustentaban diferentes interpretaciones de algunos puntos fundamentales del Derecho Natural. Entre los chamados federales, era visible desde hacía muchos años la existencia de adeptos de antiguas tradiciones jusnaturalistas que admitian la unión confederal como una de las posibles formas de _______________ *Professora Associada ao Departamento de História e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria-UFSM; coordenadora do Grupo de Pesquisa CNPq História Platina: sociedade, poder e instituições. gobierno y la de quienes estaban al tanto de la reciente experiencia norteamericana y de su vinculación com el desarollo de la libertad y la igualdad política modernas . -

Ilson Y Los Tupamaros

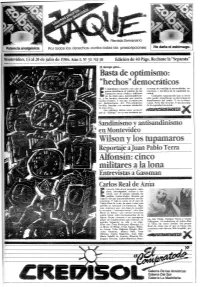

.Revista Semanario Por todos los derechos, contra todas las proscripciones . No daña el estómago. 13 al20 de julio de 1984. Año l. No 31 N$ 30 Edición de 40 Págs. Reclame la "Separata" El tiempo pasa ... Basta de optimismo: "hechos'' democráticos 1 .optimismo excesivo con que al ra tratar de conciliar la inconciliable: de gunos abordaron el reinicio de los mocracia y doctrina de la seguridad na contactos entre civiles y militares cional. no ha dado paso, lamentablemen Cualquier negociación' que se inicie te, a los hechos concretos que nuestra sólo puede desembocar en las formas de nación reclama. Y eso que, a estarse por transferencia del poder. Y en la demo las declaraciones del Vice-Almirante cracia. Neto. Sin recortes. Y sin doctrina Invidio, bastaba con sentarse ·alrededor de la seguridad nacional. de una mesa ... Los militares deben tener presente que el "diálogo" no es una instancia pa- Sandinisffio y antisandinismo en Montevideo ilson y los tupamaros Reportaje a Juan Pablo Tet·t·a Alfonsín: cinco militares a la lona Entrevistas a Gassman Carlos Real de Azúa vocar la vida de un pensador, ensa yista, investigador, crítico y do cente, por el propio cúmulo de Eperfiles intelectuales, llevaría un espacio del que lamentablemente no dis ponemos. Y más si, como en el caso de Carlos Real de Azúa, de entre todos esos perfiles se destacan los humanos. Diga mos en ton ces que, sin dejar de a ten!ler. la aversión ·-"aversión severa", dice Lisa Block de Behar- que nuestro ensayista sentía hacia toda representación de su figura, Jaque convoca a un prestigioso grupo de colaboradores para esbozar, en no, Ida Vitale, !Enrique Fierro y Carlos nuestra Separata, su vida y su obra. -

Incertidumbre Electoral, Fragmentación Política Y Coordinación De Las Elites En Contextos Multinivel

Incertidumbre Electoral, Fragmentación Política y Coordinación de las Elites en Contextos Multinivel. ¿Qué factores han determinado el armado de Listas Colectoras en la Provincia de Buenos Aires? Work in progress – Please do not cite. Autoras Natalia C. Del Cogliano Mariana L. Prats Resumen Este trabajo explora las variables que explican el emparentamiento de listas (apparentment) en la provincia de Buenos Aires. El emparentamiento de listas es un recurso significativo para la coordinación partidaria entre niveles de gobierno en un marco de desnacionalización del sistema de partidos y de territorialización de la competencia partidaria. Sin embargo, la pregunta sobre qué factores determinan su proliferación aún no ha sido respondida. La necesidad de un candidato nacional o provincial de ampliar su base de apoyo a nivel municipal a fin de reducir el nivel de incertidumbre, y de un candidato local de aprovechar el arrastre de la categoría superior en un contexto de fragmentación partidaria multinivel, teóricamente explicaría la existencia de colectoras. Por lo tanto, la variable dependiente será el número de colectoras por municipio y por partido en cada elección. Suponemos que el partido del intendente, el nivel de competencia (margen de victoria) para la elección ejecutiva local, y la concurrencia de elecciones ejecutivas provinciales pueden ser las variables explicativas del crecimiento o de la declinación en la cantidad de colectoras en cada elección. Para testear nuestra hipótesis construimos una original base de datos de todas las listas emparentadas en cada municipio y para todas las elecciones entre 1983 y 2011 en el distrito. Los hallazgos del análisis de datos son confirmados por una serie de entrevistas a actores políticos provinciales y municipales. -

URUGUAY: the Quest for a Just Society

2 URUGUAY: ThE QUEST fOR A JUST SOCiETY Uruguay’s new president survived torture, trauma and imprisonment at the hands of the former military regime. Today he is leading one of Latin America’s most radical and progressive coalitions, Frente Amplio (Broad Front). In the last five years, Frente Amplio has rescued the country from decades of economic stagnation and wants to return Uruguay to what it once was: A free, prosperous and equal society, OLGA YOLDI writes. REFUGEE TRANSITIONS ISSUE 24 3 An atmosphere of optimism filled the streets of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Montevideo as Jose Mujica assumed the presidency of Caribbean, Uruguay’s economy is forecasted to expand Uruguay last March. President Mujica, a former Tupamaro this year. guerrilla, stood in front of the crowds, as he took the Vazquez enjoyed a 70 per cent approval rate at the end oath administered by his wife – also a former guerrilla of his term. Political analysts say President Mujica’s victory leader – while wearing a suit but not tie, an accessory he is the result of Vazquez’s popularity and the economic says he will shun while in office, in keeping with his anti- growth during his time in office. According to Arturo politician image. Porzecanski, an economist at the American University, The 74-year-old charismatic new president defeated “Mujica only had to promise a sense of continuity [for the National Party’s Luis Alberto Lacalle with 53.2 per the country] and to not rock the boat.” cent of the vote. His victory was the second consecutive He reassured investors by delegating economic policy mandate for the Frente Amplio catch-all coalition, which to Daniel Astori, a former economics minister under the extends from radicals and socialists to Christian democrats Vazquez administration, who has built a reputation for and independents disenchanted with Uruguay’s two pragmatism, reliability and moderation. -

De Cliënt in Beeld

Reforming the Rules of the Game Fransje Molenaar Fransje oftheGame theRules Reforming DE CLIËNTINBEELD Party law, or the legal regulation of political parties, has be- come a prominent feature of established and newly transi- tioned party systems alike. In many countries, it has become virtually impossible to organize elections without one party or another turning to the courts with complaints of one of its competitors having transgressed a party law. At the same Reforming the Rules of the Game time, it should be recognized that some party laws are de- signed to have a much larger political impact than others. Th e development and reform of party law in Latin America It remains unknown why some countries adopt party laws that have substantial implications for party politics while other countries’ legislative eff orts are of a very limited scope. Th is dissertation explores why diff erent party laws appear as they do. It builds a theoretical framework of party law reform that departs from the Latin American experience with regulating political parties. Latin America is not necessarily known for its strong party systems or party organizations. Th is raises the important ques- tion of why Latin American politicians turn to party law, and to political parties more generally, to structure political life. Using these questions as a heuristic tool, the dissertation advances the argument that party law reforms provide politicians with access to crucial party organizational resources needed to win elections and to legislate eff ectively. Extending this argument, the dissertation identifi es threats to party organizational resources as an important force shaping adopted party law reforms. -

The United States and the Uruguayan Cold War, 1963-1976

ABSTRACT SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 In the early 1960s, Uruguay was a beacon of democracy in the Americas. Ten years later, repression and torture were everyday occurrences and by 1973, a military dictatorship had taken power. The unexpected descent into dictatorship is the subject of this thesis. By analyzing US government documents, many of which have been recently declassified, I examine the role of the US government in funding, training, and supporting the Uruguayan repressive apparatus during these trying years. Matthew Ford May 2015 SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 by Matthew Ford A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Matthew Ford Thesis Author Maria Lopes (Chair) History William Skuban History Lori Clune History For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. Permission to reproduce this thesis in part or in its entirety must be obtained from me. -

LEY DE LEMAS Supuestos De Inconstitucionalidad “Situación En La Provincia De Santa Cruz”

LEY DE LEMAS Supuestos de Inconstitucionalidad “Situación en la Provincia de Santa Cruz” CARRERA: ABOGACÍA TUTORA: VILLEGAS, NOELIA ALUMNO: GAAB, HUGO FERNANDO D.N.I.: 23.174.561 LEGAJO: VABG9925 OCTUBRE 2016 “La posibilidad de progreso político, de paz pública, de engrandecimiento nacional sólo será posible cuando el gobierno se cimiente sobre el voto popular puesto que allí donde el pueblo vota la autoridad es indiscutida.” (Carlos Pellegrini. Vice Presidente de la Nación 1890 – 1892) 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS A mi hijo Franco y a toda mi familia por acompañarme en esta importante etapa de mi vida. 2 RESUMEN La ley de lemas como sistema electoral tuvo en miras al momento de su implementación un beneficio de los ciudadanos que verían fortalecida la representativad y la democracia. Este sistema de elecciones se implementó en varias provincias argentinas que tenían un denominador común al momento de adoptarla, esto es, el partido gobernante estaba dividido por internas difíciles de resolver que afectaban su potencial electoral, por lo que se presentó a la Ley de Lemas como la forma de solucionar conflictos mayores y, a su vez, sumar los votos de las distintas corrientes internas. La cara oculta de la Ley de Lemas o de doble voto simultáneo, es que representa un verdadero fraude a la representatividad democrática ya que se trata de una herramienta que tiene el partido político gobernante para perpetuarse en el poder, y así desconocer la verdadera voluntad popular. Este sistema electoral fue adoptado por varias provincias argentinas, que luego, paulatinamente, lo fueron abandonando. En la actualidad sigue vigente en la Provincia de Santa Cruz para la elección de Gobernador y Vice, como así también, para Intendente.