Pdf Becker, Gary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarian Party National Convention | First Sitting May 22-24, 2020 Online Via Zoom

LIBERTARIAN PARTY NATIONAL CONVENTION | FIRST SITTING MAY 22-24, 2020 ONLINE VIA ZOOM CURRENT STATUS: FINAL APPROVAL DATE: 9/12/20 PREPARED BY ~~aryn ,~nn ~ar~aQ, LNC SECRETARY TABLE OF CONTENTS CONVENTION FIRST SITTING DAY 1-OPENING 3 CALL TO ORDER 3 CONVENTION OFFICIALS AND COMMITTEE CHAIRS 3 CREDENTIALS COMMITTEE REPORT 4 ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA FOR THE FIRST SITTING 7 CONVENTION FIRST SITTING DAY 1-ADJOURNMENT 16 CONVENTION FIRST SITTING DAY 2 -OPENING 16 CREDENTIALS COMMITTEE UPDATE 16 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION 18 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION QUALIFICATION TOKENS 18 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION SPEECHES 23 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 1 24 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 2 26 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 3 28 PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 4 32 CONVENTION FIRST SITTING DAY 2 -ADJOURNMENT 33 CONVENTION FIRST SITTING DAY 3 -OPENING 33 CREDENTIALS COMMITTEE UPDATE 33 VICE-PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION 35 VICE-PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION QUALIFICATION TOKENS 35 VICE-PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION SPEECHES 37 ADDRESS BY PRESIDENTIAL NOMINEE DR. JO JORGENSEN 37 VICE-PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 1 38 VICE-PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 2 39 VICE-PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION – BALLOT 3 40 STATUS OF TAXATION 41 ADJOURNMENT TO CONVENTION SECOND SITTING 41 SPECIAL THANKS 45 Appendix A – State-by-State Detail for Election Results 46 Appendix B – Election Anomalies and Other Convention Observations 53 2020 NATIONAL CONVENTION | FIRST SITTING VIA ZOOM – FINAL Page 2 LEGEND: text to be inserted, text to be deleted, unchanged existing text. All vote results, points of order, substantive objections, and rulings will be set off by BOLD ITALICS. The LPedia article for this convention can be found at: https://lpedia.org/wiki/NationalConvention2020 Recordings for this meeting can be found at the LPedia link. -

The Transhumanist Wager Zoltan Istvan

The Transhumanist Wager by Zoltan Istvan Copyright (c) 2013 Futurity Imagine Media LLC Published by Futurity Imagine Media LLC This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, business establishments, or locales is entirely coincidental. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Cover Design: Zoltan Istvan ISBN#: 978-0-9886161-1-0 Praise for Zoltan Istvan's writing and work: "Congratulations on an excellent story—really well written, concise, and elegant." Editor, National Geographic News Service "Istvan is among the correspondents I value most for his...courage." Senior Editor, The New York Times Syndicate "Thank you—you did a great interview for us." Producer, BBC Radio "Travel! Intrigue! Cannibals! Extreme journalism at far ends of Earth!" Headline featuring Zoltan Istvan, San Francisco Chronicle PART I Chapter 1 The Three Laws: 1) A transhumanist must safeguard one's own existence above all else. 2) A transhumanist must strive to achieve omnipotence as expediently as possible—so long as one's actions do not conflict with the First Law. 3) A transhumanist must safeguard value in the universe—so long as one's actions do not conflict with the First and Second Laws. —Jethro Knights' sailing log / passage to French Polynesia ************ Jethro Knights growled. His life was about to end. -

Zoltan Istvan

Zoltan Istvan Transhumanist Journalist and Entrepreneur Zoltan Istvan is often cited as the global leader of the radical science movement. A humanitarian activist and former journalist for National Geographic, Zoltan has been compared in major media to a young Al Gore and described as a modern-day Ayn Rand. Istvan is the founder of the Transhumanist Party, the author the Transhumanist Bill of Rights, and a frequently interviewed expert on AI. Before becoming an acclaimed futurist, he was a journalist for the National Geographic Channel (often an on-camera reporter) and The New York Times Syndicate. Istvan has traveled to over 100 countries, and has a degree in Philosophy and Religion from Columbia University. With his wildly popular US Presidential run as a science candidate, bestselling book The Transhumanist Wager, and powerful speeches at institutions like the World Bank, Zoltan Istvan has literally transformed transhumanism into a thriving worldwide phenomenon. He was the only presidential candidate to be interviewed by underground mega-group Anonymous. Beyond extensive media coverage, Zoltan is an eloquent, Ivy-league educated man yearning to use science, technology, reason to dramatically remake humanity. Zoltan has consulted for the US Navy as a futurist, interviewed to be Libertarian Gary Johnson's Vice President, appeared on the Joe Rogan Experience (and dozens of other shows), and gave many speeches, including at Microsoft, the Global Leaders Forum, and the Financial Times Camp Alphaville (opening Keynote). Zoltan Istvan frequently gives keynote speeches to large audiences on all topics of science, technology, and the future. As a world leader in his field, he's consulted for the US Navy, spoke at the World Bank, advised executives at multi-billion dollar corporations, moderated panels, hosted television segments, and publicly debated celebrities and policy experts. -

The Physiologist

A Publication of The American Physiological Society Experimental The Biology 2001 Abstract Physiologist Deadline Volume 43, Number 4 August 2000 November 6! EB 2001—Translating the Genome On June 26th, President Clinton walked into denced by their titles. Others will include talks the White House East Room and announced “the by leading scientists using genomics to define most wondrous map ever produced by the physiological function of a cell or a tissue. humankind.” The efforts of a public consortium However, the sessions listed are only those being led by Francis Collins and the private efforts of offered by APS. In the future, The Physiologist, Craig Venter, Celera Genomics, created a “Book the Call for Abstracts (to be mailed in of Letters,” a readout of the 3.1 billion biochem- September), and the EB and APS Home Pages ical “letters” of human DNA. These letters, will provide a listing of the wide range of ses- Inside which provide the coded instructions for a fully sions related to the “omics” listed above. functional human, will remain undecipherable However, as you are well aware, the APS por- until they are combined into words and sentences tion of the Experimental Biology meeting is not 153rd APS with meaning. just about “Translating the Genome.” It is about Business Just as APS created a new journal, all of physiology from cellular and molecular to Meeting Physiological Genomics, to provide a forum for integrative and systems to translational and clin- p. 168 the dissemination of information about the trans- ical application. It is also about professional lation of the “Book of Letters” arising from the development and social interactions. -

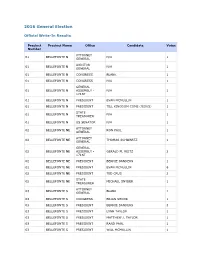

2016 General Write-In Results

2016 General Election Official Write-In Results Precinct Precinct Name Office Candidate Votes Number ATTORNEY 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 GENERAL AUDITOR 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 GENERAL 01 BELLEFONTE N CONGRESS BLANK 1 01 BELLEFONTE N CONGRESS N/A 1 GENERAL 01 BELLEFONTE N ASSEMBLY - N/A 1 171ST 01 BELLEFONTE N PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 1 01 BELLEFONTE N PRESIDENT TILL KINGDOM COME (JESUS) 1 STATE 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 TREASURER 01 BELLEFONTE N US SENATOR N/A 1 ATTORNEY 02 BELLEFONTE NE RON PAUL 1 GENERAL ATTORNEY 02 BELLEFONTE NE THOMAS SCHWARTZ 1 GENERAL GENERAL 02 BELLEFONTE NE ASSEMBLY - GERALD M. REITZ 2 171ST 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 1 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 6 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT TED CRUS 2 STATE 02 BELLEFONTE NE MICHAEL SNYDER 1 TREASURER ATTORNEY 03 BELLEFONTE S BLANK 1 GENERAL 03 BELLEFONTE S CONGRESS BRIAN SHOOK 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 3 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT LYNN TAYLOR 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT MATTHEW J. TAYLOR 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT RAND PAUL 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT WILL MCMULLIN 1 ATTORNEY 04 BELLEFONTE SE JORDAN D. DEVIER 1 GENERAL 04 BELLEFONTE SE CONGRESS JORDAN D. DEVIER 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT BURNEY SANDERS/MICHELLE OBAMA 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT DR. BEN CARSON 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT ELEMER FUDD 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLAN 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 2 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER/GEORGE M.W. -

California Statewide Direct Primary Election Tuesday, June 5, 2018

California Statewide Direct Primary Election Tuesday June 5, 2018 Polls Are Open From 7:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. on Election Day! ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ OFFICIAL VOTER INFORMATION GUIDE ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Certificate of Correctness I, Alex Padilla, Secretary of State of the State of California, do hereby certify that the measures included herein will be submitted to the electors of the State of California at the Primary Election to be held throughout the State on June 5, 2018, and that this guide has been correctly prepared in accordance with the law. Witness my hand and the Great Seal of the State in Sacramento, California, this 12th day of March, 2018. Alex Padilla, Secretary of State VOTER BILL OF RIGHTS YOU HAVE THE FOLLOWING RIGHTS: The right to vote if you are a registered voter. The right to get help casting your ballot 1 You are eligible to vote if you are: 6 from anyone you choose, except from your • a U.S. citizen living in California employer or union representative. • at least 18 years old • registered where you currently live The right to drop off your completed • not currently in state or federal prison 7 vote-by-mail ballot at any polling place in or on parole for the conviction of a California. felony • not currently found mentally The right to get election materials in a incompetent to vote by a court 8 language other than English if enough people in your voting precinct speak that language. The right to vote if you are a registered voter 2 even if your name is not on the list. -

Official Election Results

COUNTY OF CAMDEN OFFICIAL ELECTION RESULTS 2016 General Election November 8, 2016 CAM_20161108_E November 8, 2016 Summary Report Camden County Official Results Registration & Turnout 347,739 Voters Board of Chosen Freeholders (cont'd...) (343) 343/343 100.00% Election Day Turnout 186,213 53.55% REP - Claire H. GUSTAFSON 68,131 17.25% Mail-In Ballot Turnout 39,712 11.42% DEM - Edward T. MC DONNELL 127,662 32.32% Provisional Turnout 5,554 1.60% DEM - Carmen G. RODRIGUEZ 128,299 32.48% Rejected Ballots Turnout 0 0.00% Write-In 346 0.09% Emergency Turnout 0 0.00% Total ... 394,984 100.00% Total ... 231,479 66.57% Audubon Park Council (1) 1/1 100.00% US President (343) 343/343 100.00% Under Votes: 480 Under Votes: 1892 Over Votes: 0 Over Votes: 540 DEM - Dennis DELENGOWSKI 313 50.16% REP - TRUMP/PENCE 72,631 31.71% DEM - Gloria A. JONES 306 49.04% DEM - CLINTON/KAINE 146,717 64.06% Write-In 5 0.80% NON - CASTLE/BRADLEY 752 0.33% Total ... 624 100.00% NON - JOHNSON/WELD 4,245 1.85% NON - LA RIVA/PURYEAR 50 0.02% Barrington Council (5) 5/5 100.00% NON - DE LA FUENTE/STEINBERG 77 0.03% Under Votes: 2594 NON - MOOREHEAD/LILLY 74 0.03% Over Votes: 0 NON - STEIN/BARAKA 2,003 0.87% NON - KENNEDY/HART 43 0.02% DEM - Wayne ROBENOLT 2,111 49.48% DEM - Michael BEACH 2,112 49.51% Write-In 2,455 1.07% Write-In 43 1.01% Total ... 229,047 100.00% Total .. -

Presidential-Candidates-List-2020.Pdf

CANDIDATES FOR PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES Filed with the Secretary of State October 30 – November 15, 2019 REPUBLICAN CANDIDATES Wednesday, October 30, 2019 Roque “Rocky” De La Fuente, California (5440 Morehouse Drive, Ste 4000, San Diego, CA 02121) - filed in person [email protected] Tuesday, November 5, 2019 Rick Kraft, New Mexico (PO Box 850, Roswell, NM 88202-0850) – filed by mail [email protected] Thursday, November 7, 2019 Donald J. Trump, Florida (PO Box 13570, Arlington VA 22219) – filed by VP Pence [email protected] Star Locke, Texas (1821 W. Tyler, Harlingen, TX 78550) – filed by mail [email protected] Robert Ardini, New York (150 50th Ave., Apt 520, Long Island City, NY 11101) – filed by mail [email protected] Friday, November 8, 2019 Eric Merrill, New Hampshire (PO Box 375, Goffstown NH 03045) – filed in person Stephen B. Comley, Sr., Massachusetts (45 Mansion Drive, Rowley MA) 01969 – filed in person Tuesday, November 12, 2019 Bob Ely, Illinois (105 Town Line Road #328, Vernon Hills IL 60061) – filed by mail [email protected] Zoltan Istvan Gyurko, California (35 Miller Ave., 102, Mill Valley, CA 94941) – filed by mail [email protected] Matthew John Matern, California (PO Box 310, Manhattan Beach, CA 90627) – filed in person [email protected] President R. Boddie, Georgia (375 Barshey Drive, Covington, GA 30016) – filed in person [email protected] Larry Horn, Oregon (31272 Holaday Road, Scappoose, OR 97056 – filed by mail [email protected] Wednesday, November 13, 2019 Bill Weld, Massachusetts (151 Green Street, Canton MA 02021) – filed in person [email protected] Juan Payne, Alabama (PO Box 802, Theodore, AL 36590) – in person [email protected] Thursday, November 14, 2019 Joe Walsh, Illinois (PO Box 15416, Washington DC 20003) – in person [email protected] William N. -

Artificial Intelligence: Discerning a Christian Response

Article Artifi cial Intelligence: Discerning a Christian Response Derek C. Schuurman Derek C. Schuurman Artifi cial Intelligence (AI) techniques employing deep learning have recently achieved remarkable strides in tackling diffi cult problems and spurring applications in many new areas. Responses to these developments have ranged from existential fear to unbridled optimism. This technology opens up a plethora of ethical considerations and ontologi- cal questions about what it means to be human. The approach one takes to questions arising in AI is largely shaped by our philosophical presuppositions and our world- view. This article sketches some of the implications and important questions that arise surrounding AI. The article concludes by urging Christians to join this conversation, bringing insights from scripture and from Christian philosophy and theology to inform a responsible approach that contributes to the common good. he movie Wall-E is an entertain- For many decades, there have been many ing tale of a dystopian future of optimistic predictions about the capabili- Trobots, automation, and human- ties of Artifi cial Intelligence (AI) which ity. A polluted earth is left abandoned have consistently fallen short of expecta- except for robots like the charming title tions. In 1958 Frank Rosenblatt pioneered character Wall-E, who are left to clean up modeling neurons using simple networks the mess. Humans have fl ed the planet, called “perceptrons” which could be coddled aboard a massive ark-like space- trained to classify data. Later, the pioneer- ship where automated systems take care ing AI researchers Marvin Minsky and of their every need. It is striking that the Seymour Papert published an infl uential most human-like characters in the movie book titled Perceptrons which identifi ed are the two main robot characters while challenges with single-layer perceptrons the human characters are portrayed as and expressed skepticism about multi- obese, feeble, and passive, shuttled about layer perceptrons. -

Follies in Biohacking: the Transhumanist Perspective

Follies in Biohacking: The Transhumanist Perspective Jose Moreno In our insatiable quest for control and understanding, humanity has arrived at a pivotal point in its existential journey. The experiment now under the microscope, the literal surgery at hand, is that which we hold nearest, and that which holds us intact: our human body and mind. The underlying premise here is that natural selection has taken us for a wild ride of genetic randomness that lasted a millennia, and dropped us off at the intersection of technology and decision. It is up to us, whether as a society or as individuals, contentiously, to decide whether the next stage of human evolution is propelled forward by genetic enhancements, implantable micro-devices, and brain-boosting nootropics. #1 There exists a school of thought that encompasses this ideology of radical self-actualization, known as transhumanism. Transhumanists are technologists who subscribed to a techno- focused form of libertarianism. Quite literally, the goal is to become a cyborg, and use any available means of biohacking to get there, regardless of what any regulator has to say. " My brief journey through the nascent transhumanist scene started this Summer, in the culturally forward-thinking hills and tech-worshipping hacker-houses of Silicon Valley. While wandering through the Mission district of San Francisco, I happened to strike up a conversation with a guy named Zoltan Istvan, amidst a group of other people at a comedy club one night after work. Zoltan is the de facto leader of transhumanism, and is running for Governor of California to spread awareness for the movement. -

Ferrajoli, 2019

ISSN: 2448-8518 "Y nada es más fastidioso que la retórica de los derechos en los discursos ociales de cuantos los ponen por pantalla en apoyo de su poder y hasta de las violaciones de que son responsables.” Ferrajoli, 2019. Año 2020, No. 12, Enero-Abril ISSN: 2448-8518 "Y nada es más fastidioso que la retórica de los derechos en los discursos ociales de cuantos los ponen por pantalla en apoyo de su poder y hasta de las violaciones de que son responsables.” Ferrajoli, 2019. Año 2020, No. 12, Enero-Abril Derechos Fundamentales a Debate, año 2019, núm. 12, enero-abril, es una publicación cuatrimestral editada por la Comisión Estatal de Derechos Humanos, sita en, Pedro Moreno 1616, Col. Americana, Guadalajara, Jalisco, CP 44160, Tels. (33) 36691100 y 36691101, Editor titular: Comisión Estatal de Derechos Humanos. Reserva de derechos al uso exclusivo: 04-2016-072712264400-102 (impresa) y 04-2016-112411095900-203 (electrónica) otorgado por el Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor. Las opiniones vertidas en su contenido son responsabilidad exclusiva de los autores y no reflejan la postura de los editores. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de los contenidos e imágenes de la publicación sin previa autorización de la Comisión Estatal de Derechos Humanos Jalisco. Índice Presentación 8 José de Jesús Chávez Cervantes El mínimo vital en contextos de crisis sanitarias; ponde- 12 ración y umbrales de justificación: Un análisis a raíz del “Acuerdo por el que se establecen acciones extraordina- rias para la emergencia sanitaria generada por el virus Sars-cov2 (Covid-19)” emitido por la Secretaría de Salud en México. -

CYBORG MIND What Brain–Computer And

CYBORG MIND What Brain‒Computer and Mind‒Cyberspace Interfaces Mean for Cyberneuroethics CYBORG MIND Edited by Calum MacKellar Offers a valuable contribution to a conversation that promises to only grow in relevance and importance in the years ahead. Matthew James, St Mary’s University, London ith the development of new direct interfaces between the human brain and comput- Wer systems, the time has come for an in-depth ethical examination of the way these neuronal interfaces may support an interaction between the mind and cyberspace. In so doing, this book does not hesitate to blend disciplines including neurobiology, philosophy, anthropology and politics. It also invites society, as a whole, to seek a path in the use of these interfaces enabling humanity to prosper while avoiding the relevant risks. As such, the volume is the fi rst extensive study in cyberneuroethics, a subject matter which is certain to have a signifi cant impact in the twenty-fi rst century and beyond. Calum MacKellar is Director of Research of the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics, Ed- MACKELLAR inburgh, and Visiting Lecturer of Bioethics at St. Mary’s University, London. His past books EDITED BY What include (as co-editor) The Ethics of the New Eugenics (Berghahn Books, 2014). Brain‒Computer and Mind‒Cyberspace Interfaces Mean for Cyberneuroethics MEDICAL ANTHROPOLOGY EDITED BY CALUM MACKELLAR berghahn N E W Y O R K • O X F O R D Cover image by www.berghahnbooks.com Alexey Kuzin © 123RF.COM Cyborg Mind This open access edition has been made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched.