Approximations for Pi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irrational Numbers Unit 4 Lesson 6 IRRATIONAL NUMBERS

Irrational Numbers Unit 4 Lesson 6 IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Students will be able to: Understand the meanings of Irrational Numbers Key Vocabulary: • Irrational Numbers • Examples of Rational Numbers and Irrational Numbers • Decimal expansion of Irrational Numbers • Steps for representing Irrational Numbers on number line IRRATIONAL NUMBERS A rational number is a number that can be expressed as a ratio or we can say that written as a fraction. Every whole number is a rational number, because any whole number can be written as a fraction. Numbers that are not rational are called irrational numbers. An Irrational Number is a real number that cannot be written as a simple fraction or we can say cannot be written as a ratio of two integers. The set of real numbers consists of the union of the rational and irrational numbers. If a whole number is not a perfect square, then its square root is irrational. For example, 2 is not a perfect square, and √2 is irrational. EXAMPLES OF RATIONAL NUMBERS AND IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Examples of Rational Number The number 7 is a rational number because it can be written as the 7 fraction . 1 The number 0.1111111….(1 is repeating) is also rational number 1 because it can be written as fraction . 9 EXAMPLES OF RATIONAL NUMBERS AND IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Examples of Irrational Numbers The square root of 2 is an irrational number because it cannot be written as a fraction √2 = 1.4142135…… Pi(휋) is also an irrational number. π = 3.1415926535897932384626433832795 (and more...) 22 The approx. value of = 3.1428571428571.. -

Metrical Diophantine Approximation for Quaternions

This is a repository copy of Metrical Diophantine approximation for quaternions. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90637/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Dodson, Maurice and Everitt, Brent orcid.org/0000-0002-0395-338X (2014) Metrical Diophantine approximation for quaternions. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. pp. 513-542. ISSN 1469-8064 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305004114000462 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Under consideration for publication in Math. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 1 Metrical Diophantine approximation for quaternions By MAURICE DODSON† and BRENT EVERITT‡ Department of Mathematics, University of York, York, YO 10 5DD, UK (Received ; revised) Dedicated to J. W. S. Cassels. Abstract Analogues of the classical theorems of Khintchine, Jarn´ık and Jarn´ık-Besicovitch in the metrical theory of Diophantine approximation are established for quaternions by applying results on the measure of general ‘lim sup’ sets. -

Proofs, Sets, Functions, and More: Fundamentals of Mathematical Reasoning, with Engaging Examples from Algebra, Number Theory, and Analysis

Proofs, Sets, Functions, and More: Fundamentals of Mathematical Reasoning, with Engaging Examples from Algebra, Number Theory, and Analysis Mike Krebs James Pommersheim Anthony Shaheen FOR THE INSTRUCTOR TO READ i For the instructor to read We should put a section in the front of the book that organizes the organization of the book. It would be the instructor section that would have: { flow chart that shows which sections are prereqs for what sections. We can start making this now so we don't have to remember the flow later. { main organization and objects in each chapter { What a Cfu is and how to use it { Why we have the proofcomment formatting and what it is. { Applications sections and what they are { Other things that need to be pointed out. IDEA: Seperate each of the above into subsections that are labeled for ease of reading but not shown in the table of contents in the front of the book. ||||||||| main organization examples: ||||||| || In a course such as this, the student comes in contact with many abstract concepts, such as that of a set, a function, and an equivalence class of an equivalence relation. What is the best way to learn this material. We have come up with several rules that we want to follow in this book. Themes of the book: 1. The book has a few central mathematical objects that are used throughout the book. 2. Each central mathematical object from theme #1 must be a fundamental object in mathematics that appears in many areas of mathematics and its applications. -

A Short Course on Approximation Theory

A Short Course on Approximation Theory N. L. Carothers Department of Mathematics and Statistics Bowling Green State University ii Preface These are notes for a topics course offered at Bowling Green State University on a variety of occasions. The course is typically offered during a somewhat abbreviated six week summer session and, consequently, there is a bit less material here than might be associated with a full semester course offered during the academic year. On the other hand, I have tried to make the notes self-contained by adding a number of short appendices and these might well be used to augment the course. The course title, approximation theory, covers a great deal of mathematical territory. In the present context, the focus is primarily on the approximation of real-valued continuous functions by some simpler class of functions, such as algebraic or trigonometric polynomials. Such issues have attracted the attention of thousands of mathematicians for at least two centuries now. We will have occasion to discuss both venerable and contemporary results, whose origins range anywhere from the dawn of time to the day before yesterday. This easily explains my interest in the subject. For me, reading these notes is like leafing through the family photo album: There are old friends, fondly remembered, fresh new faces, not yet familiar, and enough easily recognizable faces to make me feel right at home. The problems we will encounter are easy to state and easy to understand, and yet their solutions should prove intriguing to virtually anyone interested in mathematics. The techniques involved in these solutions entail nearly every topic covered in the standard undergraduate curriculum. -

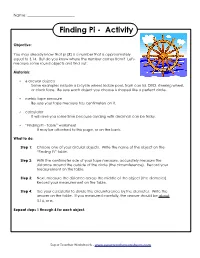

Finding Pi Project

Name: ________________________ Finding Pi - Activity Objective: You may already know that pi (π) is a number that is approximately equal to 3.14. But do you know where the number comes from? Let's measure some round objects and find out. Materials: • 6 circular objects Some examples include a bicycle wheel, kiddie pool, trash can lid, DVD, steering wheel, or clock face. Be sure each object you choose is shaped like a perfect circle. • metric tape measure Be sure your tape measure has centimeters on it. • calculator It will save you some time because dividing with decimals can be tricky. • “Finding Pi - Table” worksheet It may be attached to this page, or on the back. What to do: Step 1: Choose one of your circular objects. Write the name of the object on the “Finding Pi” table. Step 2: With the centimeter side of your tape measure, accurately measure the distance around the outside of the circle (the circumference). Record your measurement on the table. Step 3: Next, measure the distance across the middle of the object (the diameter). Record your measurement on the table. Step 4: Use your calculator to divide the circumference by the diameter. Write the answer on the table. If you measured carefully, the answer should be about 3.14, or π. Repeat steps 1 through 4 for each object. Super Teacher Worksheets - www.superteacherworksheets.com Name: ________________________ “Finding Pi” Table Measure circular objects and complete the table below. If your measurements are accurate, you should be able to calculate the number pi (3.14). Is your answer name of circumference diameter circumference ÷ approximately circular object measurement (cm) measurement (cm) diameter equal to π? 1. -

Rational Numbers Vs. Irrational Numbers Handout

Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers by Nabil Nassif, PhD in cooperation with Sophie Moufawad, MS and the assistance of Ghina El Jannoun, MS and Dania Sheaib, MS American University of Beirut, Lebanon An MIT BLOSSOMS Module August, 2012 Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers “The ultimate Nature of Reality is Numbers” A quote from Pythagoras (570-495 BC) Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers “Wherever there is number, there is beauty” A quote from Proclus (412-485 AD) Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers Traditional Clock plus Circumference 1 1 min = of 1 hour 60 Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers An Electronic Clock plus a Calendar Hour : Minutes : Seconds dd/mm/yyyy 1 1 month = of 1year 12 1 1 day = of 1 year (normally) 365 1 1 hour = of 1 day 24 1 1 min = of 1 hour 60 1 1 sec = of 1 min 60 Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers TSquares: Use of Pythagoras Theorem Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers Golden number ϕ and Golden rectangle 1+√5 1 1 √5 Roots of x2 x 1=0are ϕ = and = − − − 2 − ϕ 2 Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers Golden number ϕ and Inner Golden spiral Drawn with up to 10 golden rectangles Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers Outer Golden spiral and L. Fibonacci (1175-1250) sequence = 1 , 1 , 2, 3, 5, 8, 13..., fn, ... : fn = fn 1+fn 2,n 3 F { } − − ≥ f1 f2 1 n n 1 1 !"#$ !"#$ fn = (ϕ +( 1) − ) √5 − ϕn Rational numbers vs. Irrational numbers Euler’s Number e 1 1 1 s = 1 + + + =2.6666....66.... 3 1! 2 3! 1 1 1 s = 1 + + + =2.70833333...333... -

The Evolution of Numbers

The Evolution of Numbers Counting Numbers Counting Numbers: {1, 2, 3, …} We use numbers to count: 1, 2, 3, 4, etc You can have "3 friends" A field can have "6 cows" Whole Numbers Whole numbers are the counting numbers plus zero. Whole Numbers: {0, 1, 2, 3, …} Negative Numbers We can count forward: 1, 2, 3, 4, ...... but what if we count backward: 3, 2, 1, 0, ... what happens next? The answer is: negative numbers: {…, -3, -2, -1} A negative number is any number less than zero. Integers If we include the negative numbers with the whole numbers, we have a new set of numbers that are called integers: {…, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, …} The Integers include zero, the counting numbers, and the negative counting numbers, to make a list of numbers that stretch in either direction indefinitely. Rational Numbers A rational number is a number that can be written as a simple fraction (i.e. as a ratio). 2.5 is rational, because it can be written as the ratio 5/2 7 is rational, because it can be written as the ratio 7/1 0.333... (3 repeating) is also rational, because it can be written as the ratio 1/3 More formally we say: A rational number is a number that can be written in the form p/q where p and q are integers and q is not equal to zero. Example: If p is 3 and q is 2, then: p/q = 3/2 = 1.5 is a rational number Rational Numbers include: all integers all fractions Irrational Numbers An irrational number is a number that cannot be written as a simple fraction. -

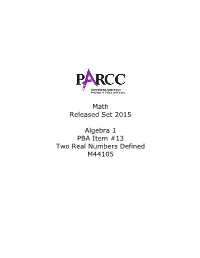

Control Number: FD-00133

Math Released Set 2015 Algebra 1 PBA Item #13 Two Real Numbers Defined M44105 Prompt Rubric Task is worth a total of 3 points. M44105 Rubric Score Description 3 Student response includes the following 3 elements. • Reasoning component = 3 points o Correct identification of a as rational and b as irrational o Correct identification that the product is irrational o Correct reasoning used to determine rational and irrational numbers Sample Student Response: A rational number can be written as a ratio. In other words, a number that can be written as a simple fraction. a = 0.444444444444... can be written as 4 . Thus, a is a 9 rational number. All numbers that are not rational are considered irrational. An irrational number can be written as a decimal, but not as a fraction. b = 0.354355435554... cannot be written as a fraction, so it is irrational. The product of an irrational number and a nonzero rational number is always irrational, so the product of a and b is irrational. You can also see it is irrational with my calculations: 4 (.354355435554...)= .15749... 9 .15749... is irrational. 2 Student response includes 2 of the 3 elements. 1 Student response includes 1 of the 3 elements. 0 Student response is incorrect or irrelevant. Anchor Set A1 – A8 A1 Score Point 3 Annotations Anchor Paper 1 Score Point 3 This response receives full credit. The student includes each of the three required elements: • Correct identification of a as rational and b as irrational (The number represented by a is rational . The number represented by b would be irrational). -

Evaluating Fourier Transforms with MATLAB

ECE 460 – Introduction to Communication Systems MATLAB Tutorial #2 Evaluating Fourier Transforms with MATLAB In class we study the analytic approach for determining the Fourier transform of a continuous time signal. In this tutorial numerical methods are used for finding the Fourier transform of continuous time signals with MATLAB are presented. Using MATLAB to Plot the Fourier Transform of a Time Function The aperiodic pulse shown below: x(t) 1 t -2 2 has a Fourier transform: X ( jf ) = 4sinc(4π f ) This can be found using the Table of Fourier Transforms. We can use MATLAB to plot this transform. MATLAB has a built-in sinc function. However, the definition of the MATLAB sinc function is slightly different than the one used in class and on the Fourier transform table. In MATLAB: sin(π x) sinc(x) = π x Thus, in MATLAB we write the transform, X, using sinc(4f), since the π factor is built in to the function. The following MATLAB commands will plot this Fourier Transform: >> f=-5:.01:5; >> X=4*sinc(4*f); >> plot(f,X) In this case, the Fourier transform is a purely real function. Thus, we can plot it as shown above. In general, Fourier transforms are complex functions and we need to plot the amplitude and phase spectrum separately. This can be done using the following commands: >> plot(f,abs(X)) >> plot(f,angle(X)) Note that the angle is either zero or π. This reflects the positive and negative values of the transform function. Performing the Fourier Integral Numerically For the pulse presented above, the Fourier transform can be found easily using the table. -

February 2009

How Euler Did It by Ed Sandifer Estimating π February 2009 On Friday, June 7, 1779, Leonhard Euler sent a paper [E705] to the regular twice-weekly meeting of the St. Petersburg Academy. Euler, blind and disillusioned with the corruption of Domaschneff, the President of the Academy, seldom attended the meetings himself, so he sent one of his assistants, Nicolas Fuss, to read the paper to the ten members of the Academy who attended the meeting. The paper bore the cumbersome title "Investigatio quarundam serierum quae ad rationem peripheriae circuli ad diametrum vero proxime definiendam maxime sunt accommodatae" (Investigation of certain series which are designed to approximate the true ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter very closely." Up to this point, Euler had shown relatively little interest in the value of π, though he had standardized its notation, using the symbol π to denote the ratio of a circumference to a diameter consistently since 1736, and he found π in a great many places outside circles. In a paper he wrote in 1737, [E74] Euler surveyed the history of calculating the value of π. He mentioned Archimedes, Machin, de Lagny, Leibniz and Sharp. The main result in E74 was to discover a number of arctangent identities along the lines of ! 1 1 1 = 4 arctan " arctan + arctan 4 5 70 99 and to propose using the Taylor series expansion for the arctangent function, which converges fairly rapidly for small values, to approximate π. Euler also spent some time in that paper finding ways to approximate the logarithms of trigonometric functions, important at the time in navigation tables. -

Approximation Atkinson Chapter 4, Dahlquist & Bjork Section 4.5

Approximation Atkinson Chapter 4, Dahlquist & Bjork Section 4.5, Trefethen's book Topics marked with ∗ are not on the exam 1 In approximation theory we want to find a function p(x) that is `close' to another function f(x). We can define closeness using any metric or norm, e.g. Z 2 2 kf(x) − p(x)k2 = (f(x) − p(x)) dx or kf(x) − p(x)k1 = sup jf(x) − p(x)j or Z kf(x) − p(x)k1 = jf(x) − p(x)jdx: In order for these norms to make sense we need to restrict the functions f and p to suitable function spaces. The polynomial approximation problem takes the form: Find a polynomial of degree at most n that minimizes the norm of the error. Naturally we will consider (i) whether a solution exists and is unique, (ii) whether the approximation converges as n ! 1. In our section on approximation (loosely following Atkinson, Chapter 4), we will first focus on approximation in the infinity norm, then in the 2 norm and related norms. 2 Existence for optimal polynomial approximation. Theorem (no reference): For every n ≥ 0 and f 2 C([a; b]) there is a polynomial of degree ≤ n that minimizes kf(x) − p(x)k where k · k is some norm on C([a; b]). Proof: To show that a minimum/minimizer exists, we want to find some compact subset of the set of polynomials of degree ≤ n (which is a finite-dimensional space) and show that the inf over this subset is less than the inf over everything else. -

WHY a DEDEKIND CUT DOES NOT PRODUCE IRRATIONAL NUMBERS And, Open Intervals Are Not Sets

WHY A DEDEKIND CUT DOES NOT PRODUCE IRRATIONAL NUMBERS And, Open Intervals are not Sets Pravin K. Johri The theory of mathematics claims that the set of real numbers is uncountable while the set of rational numbers is countable. Almost all real numbers are supposed to be irrational but there are few examples of irrational numbers relative to the rational numbers. The reality does not match the theory. Real numbers satisfy the field axioms but the simple arithmetic in these axioms can only result in rational numbers. The Dedekind cut is one of the ways mathematics rationalizes the existence of irrational numbers. Excerpts from the Wikipedia page “Dedekind cut” A Dedekind cut is а method of construction of the real numbers. It is a partition of the rational numbers into two non-empty sets A and B, such that all elements of A are less than all elements of B, and A contains no greatest element. If B has a smallest element among the rationals, the cut corresponds to that rational. Otherwise, that cut defines a unique irrational number which, loosely speaking, fills the "gap" between A and B. The countable partitions of the rational numbers cannot result in uncountable irrational numbers. Moreover, a known irrational number, or any real number for that matter, defines a Dedekind cut but it is not possible to go in the other direction and create a Dedekind cut which then produces an unknown irrational number. 1 Irrational Numbers There is an endless sequence of finite natural numbers 1, 2, 3 … based on the Peano axiom that if n is a natural number then so is n+1.