Burkina Faso: Extremism & Counter-Extremism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burkina Faso Burkina

Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source Vulnerability, Poverty, June 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 16130_Burkina_Faso_Report_CVR.indd 3 7/14/17 12:49 PM Burkina Faso Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source June 2016 Poverty Global Practice Africa Region Report No. 115122 Document of the World Bank For Official Use Only 16130_Burkina_Faso_Report.indd 1 7/14/17 12:05 PM © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. -

State of Food Security in Burkina Faso Fews Net Update for January-February, 2001

The USAID Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) (Réseau USAID du Système d’Alerte Précoce contre la Famine) 01 BP 1615 Ouagadougou 01, Burkina Faso, West Africa Tel/Fax: 226-31-46-74. Email: [email protected] STATE OF FOOD SECURITY IN BURKINA FASO FEWS NET UPDATE FOR JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 2001 February 25, 2001 HIGHLIGHTS Food insecurity continues to worsen in the center plateau, north, and Sahel regions, prompting the government to call for distributions and subsidized sales of food between February and August in food insecure areas. Basic food commodities remained available throughout the country in February. Millet, the key food staple, showed no price movements that would suggest unusual scarcities in the main markets compared to prices in February 2000 or average February prices. Nevertheless, millet prices rose 40-85 % above prices a year ago in secondary markets in the north and Sahel regions, respectively. These sharp price rises stem from the drop in cereal production in October-November following the abrupt end of the rains in mid-August. Unfortunately, the lack of good roads reduces trader incentives to supply cereals to those areas. Consequently, prices have been increasing quickly due to increasing demand from households that did not harvest enough. Throughout the north and Sahel regions, most households generally depend on the livestock as their main source of income. Ironically this year, when millet prices are rising, most animal prices have fallen drastically due to severe shortages of water and forage. To make matters worse, animal exports to Ivory Coast, which used to be a very profitable business, are no longer a viable option following the ethnic violence that erupted in that country a few months ago. -

Burkina Faso 2020 Human Rights Report

BURKINA FASO 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Burkina Faso is a constitutional republic led by an elected president. On November 22, the country held presidential and legislative elections despite challenges due to growing insecurity and increasing numbers of internally displaced persons. President Roch Marc Christian Kabore was re-elected to a second five-year term with 57.74 percent of the popular vote, and his party--the People’s Movement for Progress--won 56 seats in the 127-seat National Assembly, remaining the largest party in a legislative majority coalition with smaller parties. National and international observers characterized the elections as peaceful and “satisfactory,” while noting logistical problems on election day and a lack of access to the polls for many citizens due to insecurity. The government had previously declared that elections would take place only in areas where security could be guaranteed. The Ministry of Internal Security and the Ministry of Defense are responsible for internal security. The Ministry of Internal Security oversees the National Police. The army, air force, and National Gendarmerie, which operate within the Ministry of Defense, are responsible for external security but sometimes assist with missions related to domestic security. On January 21, the government passed legislation formalizing community-based self-defense groups by establishing the Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland, a civilian support corps for state counterterrorism efforts with rudimentary oversight from the -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

Ceni - Burkina Faso

CENI - BURKINA FASO ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES DU 22/05/2016 STATISTIQUES DES BUREAUX DE VOTE PAR COMMUNES \ ARRONDISSEMENTS LISTE DEFINITIVE CENI 22/05/2016 REGION : BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN PROVINCE : BALE COMMUNE : BAGASSI Secteur/Village Emplacement Bureau de vote Inscrits ASSIO ASSIO II\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 355 BADIE ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 243 BAGASSI ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 440 BAGASSI ECOLE Bureau de vote 2 403 BAGASSI TINIEYIO\ECOLE Bureau de vote 2 204 BAGASSI TINIEYIO\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 439 BANDIO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 331 BANOU ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 320 BASSOUAN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 252 BOUNOU ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 358 BOUNOU ECOLE2\ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 331 DOUSSI ECOLE B Bureau de vote 1 376 HAHO CENTRE\CENTRE ALPHABETISATION Bureau de vote 1 217 KAHIN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 395 KAHO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 349 KANA ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 323 KAYIO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 303 KOUSSARO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 419 MANA ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 458 MANA ECOLE Bureau de vote 2 451 MANZOULE MANZOULE\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 166 MOKO HANGAR Bureau de vote 1 395 NIAGA NIAGA\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 198 NIAKONGO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 357 OUANGA OUANGA\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 164 PAHIN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 378 SAYARO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 465 SIPOHIN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 324 SOKOURA ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 184 VY ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 534 VY ECOLE2\ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 453 VYRWA VIRWA\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 141 YARO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 481 Nombre de bureaux de la commune 33 Nombre d'inscrits de la commune 11 207 CENI/ Liste provisoire -

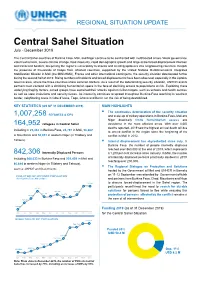

Central Sahel Situation July - December 2019

REGIONAL SITUATION UPDATE Central Sahel Situation July - December 2019 The Central Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger continue to be confronted with multifaceted crises. Weak governance, violent extremism, severe climate change, food insecurity, rapid demographic growth and large-scale forced displacement intersect and transcend borders, deepening the region’s vulnerability to shocks and creating spillovers into neighbouring countries. Despite the presence of thousands of troops from affected countries, supported by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (the MINUSMA), France and other international contingents, the security situation deteriorated further during the second half of 2019. Rising numbers of incidents and forced displacements have been observed, especially in the Liptako- Gourma area, where the three countries share common borders. As a result of the deteriorating security situation, UNHCR and its partners must contend with a shrinking humanitarian space in the face of declining access to populations at risk. Exploiting these underlying fragility factors, armed groups have sustained their attacks against civilian targets, such as schools and health centres, as well as state institutions and security forces. As insecurity continues to spread throughout Burkina Faso reaching its southern border, neighboring areas in Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Ghana and Benin run the risk of being destabilized. KEY STATISTICS (AS OF 31 DECEMBER 2019) MAIN HIGHLIGHTS ▪ The continuous deterioration of the security situation 1,007,258 REFUGEES & IDPS and scale-up of military operations in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger drastically limits humanitarian access and 164,952 refugees in Central Sahel assistance in the most affected areas. With over 4,000 deaths reported, 2019 saw the highest annual death toll due Including in 25,442 in Burkina Faso, 24,797 in Mali, 56,662 to armed conflict in the region since the beginning of the in Mauritania and 58,051 in western Niger (in Tillabery and conflict in Mali in 2012. -

Country Profiles

Global Coalition EDUCATION UNDER ATTACK 2020 GCPEA to Protect Education from Attack COUNTRY PROFILES BURKINA FASO The frequency of attacks on education in Burkina Faso increased during the reporting period, with a sharp rise in attacks on schools and teachers in 2019. Over 140 incidents of attack – including threats, military use of schools, and physical attacks on schools and teachers – took place within a broader climate of insecurity, leading to the closure of over 2,000 educational facilities. Context The violence that broke out in northern Burkina Faso in 2015, and which spread southward in subsequent years,331 es- calated during the 2017-2019 reporting period.332 Ansarul Islam, an armed group that also operated in Mali, perpetrated an increasing number of attacks in Soum province, in the Sahel region, throughout 2016 and 2017.333 Other armed groups, including Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliate, Groupfor the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), as well as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), also committed attacks against government buildings, and civilian structures such as restaurants, schools, and churches, targeting military posts.334 Since the spring of 2017, the government of Burkina Faso has under- taken military action against armed groups in the north, including joint operations with Malian and French forces.335 Data from the UN Department for Safety and Security (UNDSS) demonstrated increasing insecurity in Burkina Faso during the reporting period. Between January and September 2019, 478 security incidents reportedly occurred, more than dur- ing the entire period between 2015 and 2018 (404).336 These incidents have extensively affected civilians. -

Project No. DSH-4000000964 Final Narrative Report

Border Security and Management in the Sahel - Phase II Project No. DSH-4000000964 Final Narrative Report In Fafa (Gao Region, Mali), a group of young girls take part in a recreational activity as a prelude to an awareness-raising session on the risks associated with the presence of small arms and light weapons in the community (March 2019) Funded by 1 PROJECT INFORMATION Name of Organization: Danish Refugee Council – Danish Demining Group (DRC-DDG) Project Title: Border Security and Management in the Sahel – Phase II Grant Agreement #: DSH-4000000964 Amount of funding allocated: EUR 1 600 000 Project Duration: 01/12/2017 – 30/09/2019 Countries: Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger Sites/Locations: Burkina Faso: Ariel, Nassoumbou, Markoye, Tokabangou, Thiou, Nassoumbou, Ouahigouya Mali: Fafa, Labbezanga, Kiri, Bih, Bargou Niger: Koutougou, Kongokiré, Amarsingue, Dolbel, Wanzarbe Number of beneficiaries: 17 711 beneficiaries Sustainable Development Goal: Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions Date of final report 30/01/2020 Reporting Period: 01/12/2017 – 30/09/2019 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Border Security and Management Programme was launched in 2014 by the Danish Demining Group’s (DDG). Designed to improve border management and security in the Liptako Gourma region (border area shared by Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger), the programme applies an innovative and community-based cross-border approach in the interests of the communities living in the border zones, with the aim of strengthening the resilience of those communities to conflict and -

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief January 2020 UNICEF January 2020 Central Sahel Advocacy Brief A Children under attack The surge in armed violence across Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger is having a devastating impact on children’s survival, education, protection and development. The Sahel, a region of immense potential, has long been one of the most vulnerable regions in Africa, home to some countries with the lowest development indicators globally. © UNICEF/Juan Haro Cover image: © UNICEF/Vincent Tremeau The sharp increase in armed attacks on communities, schools, health centers and other public institutions and infrastructures is at unprecedented levels. Violence is disrupting livelihoods and access to social services including education and health care. Insecurity is worsening chronic vulnerabilities including high levels of malnutrition, poor access to clean water and sanitation facilities. As of November 2019, 1.2 million people are displaced, of whom more than half are children.1 This represents a two-fold increase in people displaced by insecurity and armed conflict in the Central Sahel countries in the past 12 months, and a five-fold increase in Burkina Faso alone.* Reaching those in need is increasingly challenging. During the past year, the rise in insecurity, violence and military operations has hindered access by humanitarian actors to conflict-affected populations. The United Nations Integrated Strategy for the Sahel (UNISS) continues to spur inter-agency cooperation. UNISS serves as the regional platform to galvanize multi-country and cross-border efforts to link development, humanitarian and peace programming (triple nexus). Partners are invited to engage with the UNISS platform to scale-up action for resilience, governance and security. -

GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 3950

GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 3950 GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com TERRORIST ATTACKS AND THE INFLUENCE OF ILLICIT OR HARD DRUGS: IMPLICATIONS TO BORDER SECURITY IN WEST AFRICA Dr. Temitope Francis Abiodun Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria [email protected] +2348033843918 Gbadamosi Musa M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Damilola Adeyinka M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Anthony Ifeanyichukwu Ndubuisi M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Joshua Akande M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Omoyele Ayomikun Adeniran M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Adesina Mukaila Funso M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Chiamaka Ugbor Precious M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria Abayomi Olawale Quadri M.A. Student, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies University of Ibadan, Nigeria GSJ© 2020 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 2, February 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 3951 ABSTRACT The West African sub-region has experienced a devastating surge in terrorist attacks against civilian and military targets for over one and half decades now. And this has remained one of the main obstacles to sustenance of peaceful co-existence in the region. This is evident in the myriads of terrorist attacks from the various terrorist and insurgent groups across West African borders: Boko Haram, ISWAP (Islamic State West African Province), Al-Barakat, Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa. -

Nord Est Mopti Gao Sahel Tombouctou Centre-Nord

BURKINA FASO - Border aTourpéeré a with Mali and Niger - Basemap Tina Erdan Boubanki Fatafali Tondibongo Narki Gonta Timbadior Samangolo Abinda Mali Drougama Gouélèy Nassouma Sossa Kobahi Bilantal Niger Barkoussi Tkiri Kantakin Dakabiba Dakafiountou Bounti Férendi Dounda Ngaghoy Bougueydi Kissim Dakakouko Burkina Faso Tila Kormi Gogoro Garmi Toundourou Ouami Timbsèy TOMBOUCTOU Toua Banga Gamra Lougui Dèmbéré Ti-N-Alabi Benin Tanga Ouro Fassi Tièmbourou Ouari Kéri GAO Tyoumguel Nokara Hoandi Dara Alabi Tilèya Ghana Kikiri Tyama Simbi Côte Ama Siguiri Ourokoymankobé Boussigui Dossou Douni Omga Ouro Nguérou Piringa Yorbou d'Ivoire Boussouma Torobani Tionbou Douna Kobou Nissanata Loro Gai Gandébalo Grimari-Débéré Boundou Soué TOMBOUCTOU Nani Ogui Guittiram Boni Loro Kirnya Ti-N-Dialali Ela Boni Ouro Hamdi GAO Koyo Habe Gaganba Dyamaga Tabi Issoua Boumboum MALI Bebi Dougoussa Sarabango Nemguéne Toupéré Oussoua Gassèy MOPTI Tandi Téga TILLABERI Fété Noti Diamé MALI Beli Guéddérou SAHEL NIGER Sébéndourou Tin-Akoff NORD TIN-AKOFF BURKINA FASO Dioumdiouréré Yogododji Isèy Sèrma Toulévèndou Péto Kobi Tiguila Tassa Walda EST Korkana Godowaré Boundouérou Sambaladio Gomnigori (H) (H) Tindaratane Haini (H) LEGEND Saré Dina Kassa (H) Banguere Gangani Wanzerbe I (H) Country capital MOPTI Kobou MARKOYE Wanzerbe Boukari Koira Bolo Kogo DEOU Boukary Koira Mondoro Moniékana Oursi Boulokogo Region (adm. 1) Niangassagou Kassa (H) Gountouyena Bangou Markoye Yirma Douna OURSI Ndieleye (H) (Va) Tanda Banay Takabougou Ne-Kossa Province (adm. 2) Toïkana Déou Borobon -

Of Islamist Terrorist Attacks

ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD 1979-2019 NOVEMBER 2019 ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD 1979-2019 NOVEMBER 2019 ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD 1979-2019 Editor Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique Editorial coordination Victor DELAGE, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE Production Loraine AMIC, Victor DELAGE, Virginie DENISE, Anne FLAMBERT, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Sasha MORINIÈRE, Dominique REYNIÉ, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE Proofreading Francys GRAMET, Claude SADAJ Graphic design Julien RÉMY Printer GALAXY Printers Published November 2019 ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD Table of contents An evaluation of Islamist violence in the world (1979-2019), by Dominique Reynié .....................................................6 I. The beginnings of transnational Islamist terrorism (1979-2000) .............12 1. The Soviet-Afghan War, "matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism” .................................. 12 2. The 1980s and the emergence of Islamist terrorism .............................................................. 13 3. The 1990s and the spread of Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa ........................................................................................... 16 4. The export of jihad ................................................................................................................. 17 II. The turning point of 9/11 (2001-2012) ......................................................21