MEASURES AFFECTING ALCOHOLIC and MALT BEVERAGES Report of the Panel Adopted on 19 June 1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OARDC HCS 0491.Pdf (7.500Mb)

PROCEEDINGS SHO Horticulture Department Series 491 January 1980 OHIO AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH ~~W' WOOSTER, 0 CONTENTS Page No. The Effective Use of Fungicides for Controlling Grape Diseases 1 by M. A. Ell is The Grape Industry in Virginia 4 by E.L. Phillips , Developing a Wine Industry in Mississippi.............................. 8 by R.P. Vine, B.J. Stojanovic, C.P. Hegwood, Jr., J.P. Overcash and F.L. Shuman, Jr. Use of Methiocarb in Ohio Grapes •...................................... 12 by R.N. Williams Maintaining Correct Levels of Free Sulfur Dioxide in Wines 14 by J.F. Ga11ander and J.R. Liu Centrifugation of Musts and Wines 18 by F. Krampe Microbiological Testing for Predicting Wine Stability 24 by A. Haffenreffer Importance of Determining Volatile Acidity in Wines 26 by J.F. Gallander Preliminary Observations of Cluster-Thinning and Shoot-Tip Removal On 'Seyval' Grapevines, by G.R. Nonnecke 29 Concepts of Making Red Table Wines 32 by R.P. Vine Environment and the Variety............................................ 38 by E. L. Ph i 11 i ps Integrated Pest Management and You ~................ 44 by F. R. Ha 11 A Progress Report on the Effects of Rootstocks on Five Grape Cultivars.. 49 by G.A. Cahoon and D.A. Chandler PREFACE Approximately 150 persons attended the 1980 Ohio Grape-Wine Short Course, which was held at the Fawcett Center for Tomorrow, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, on January 29-30. Those attending were from 9 states not including Ohio and represented many areas of the grape and wine industry. This course was sponsored by the Department of Horticulture, The Ohio State University, in coopera tion with Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Ohio Cooperative Ex tension Service and Ohio Wine Producers Association. -

American Wine Society News

AMERICAN WINE SOCIETY® NEWS Promoting Appreciation of Wine Through Education Volume 31, No. 4 www.americanwinesociety.org August-September 2017 What’s Inside Boost Your Wine Smarts Aaron Mandel 2017 National Conference 16 50th Anniversary Activities 6 Wine Judge Training Year one of the Wine Judge Certification Program, to Amazon Smile 3 be held at the conference, is already sold out. This is not really a surprise because the program is usually Awards Nominations 11 full by the end of May these days, and we are al- ready receiving inquiries about the 2018 program. AWSEF Scholarship Awards 15 So, it is quite likely next year will sell out early as well. If you are interested in the program, please do not delay—apply right after Chapter Events 7 the November conference is over. Government Affairs 6 The sell-out of the Wine Judge Certification Program does not mean that there will be any lack of educational opportunities at the con- Learning from Wine Competition 5 ference. There are, of course, the many fine sessions for us to take Member Service News 4 advantage of, plus our new Super Tasting Series—Level I program. This is a full-day class that takes place on Nov. 2. It offers a begin- National Tasting Project 4 ning education about the primary wine varieties and regions in the world, along with an opportunity to taste wines from many of those Reflections on Silver 5 regions. We offered this program for the first time last year, and the reviews were overwhelmingly positive. Those who pass the Treasurer’s Report 12 exam are awarded a certificate. -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on RESTRICTED DS23/R 16 March 1992 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON RESTRICTED DS23/R 16 March 1992 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution UNITED STATES - MEASURES AFFECTING ALCOHOLIC AND MALT BEVERAGES Report of the Panei 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 On 7 March and on 16 April 1991, Canada held consultations with the United States under Article XXIII:1 concerning measures relating to imported beer, wine and cider. The consultations did not result in a mutually satisfactory solution of these matters, and Canada requested the establishment of a GATT panel under Article XXIII:2 to examine the matter (DS23/2 of 12 April 1991). 1.2 At its meeting of 29-30 May 1991, the Council agreed to establish a panel and authorized the Council Chairman to designate the Chairman and members of the Panel in consultation with the parties concerned (C/M/250, page 35). 1.3 The terms of reference of the Panel are as follows: "To examine, in the light of the relevant GATT provisions, the matter referred to the CONTRACTING PARTIES by Canada in document DS23/2 and to make such findings as will assist the CONTRACTING PARTIES in making the recommendations or in giving the rulings provided for in Article XXIII:2.* The parties subsequently agreed that the above terms of reference should include reference to documents DS23/1, DS23/2 and DS23/3 (DS23/4). 1.4 Pursuant to the authorization by the Council, and after securing the agreement of the parties concerned, the Chairman of the Council notified the following composition of the Panel on 8 July 1991 (DS23/4): Chairman: Mr. Julio Lacarte-Muro Members: Ms. -

2019 Sommelier Challenge San Diego, CA September 20, 2019

2019 Sommelier Challenge San Diego, CA September 20, 2019 Adkins Family Vineyard 2017 Adkins Family Vineyards Great White Wine Alta Mesa Estate Vineyards Best Viognier 90 2018 Adkins Family Vineyards Zinfandel Alta Mesa Estate Vineyards Gold 91 2017 Adkins Family Vineyards Great White Wine Alta Mesa Estate Vineyards Gold 90 2018 Adkins Family Vineyards Chardonnay Alta Mesa Estate Vineyards Silver Alexander Valley Vineyards 2017 Alexander Valley Vineyards Homestead Red Alexander Valley Gold 90 Blend 2018 Alexander Valley Vineyards Dry Rose of Alexander Valley Gold 90 Sangiovese 2017 Alexander Valley Vineyards Merlot Alexander Valley Silver Allen Estate Wines 2016 Allen Wines Audacieux Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley Sugarloaf Gold 90 Mountain Vineyard 2016 Allen Wines Audacieux Cabernet Sauvignon Sonoma County Knights Link Gold 91 Vineyard 2017 Allen Wines Audacieux Pinot Noir Sonoma County King Arthur Silver Vineyard Arterra Wines 2016 Arterra Wines Petit Verdot Virginia Gold 92 2017 Arterra Wines Tannat Virginia Faquier County Gold 92 AUTRY CELLARS 2013 Autry Cellars Petite Sirah Paso Robles Silver 2013 Autry Cellars Tertian Harmony Paso Robles Silver Avanguardia Wines 2015 Avanguardia AMPIO Sierra Foothills Gold 90 2013 Avanguardia PREMIATO Sierra Foothills Gold 90 2011 Avanguardia SANGINETO Sierra Foothills Silver Axios Inc 2015 Kalaris Pinot Noir Sonoma Coast Gold 92 2014 Kalaris Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley Gold 90 2015 Kalaris Merlot Napa Valley Gold 90 2017 Kalaris Chardonnay Napa Valley Silver 2015 Philotimo Red Table Wine Napa -

Agreement Between the United States of America and the European Community on Trade in Wine

AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ON TRADE IN WINE USA/CE/en 1 The UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, hereafter "the United States", and • The EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, hereafter "the Community", hereafter referred to jointly as "the Parties", RECOGNIZING that the Parties desire to establish closer links in the wine sector, DETERMINED to foster the development of trade in wine within the framework of increased mutual understanding, RESOLVED to provide a harmonious environment for addressing wine trade issues between the Parties, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: USA/CE/en 2 • TITLE I INITIAL PROVISIONS ARTICLE 1 Objectives The objectives of this Agreement are: (a) to facilitate trade in wine between the Parties and to improve cooperation in the development and enhance the transparency of regulations affecting such trade; (b) to lay the foundation, as the first phase, for broad agreement on trade in wine between the Parties; and (c) to provide a framework for continued negotiations in the wine sector. USA/CE/en 3 ARTICLE 2 • Definitions For the purposes of this Agreement: (a) "wine-making practice" means a process, treatment, technique or material used to produce wine; (b) "COLA" means a Certificate of Label Approval or a Certificate of Exemption from Label Approval that results from an approved Application for and Certification/Exemption of Label/Bottle Approval, as required under U.S. federal laws and regulations and issued by the U.S. Government that includes a set of all labels approved to be firmly affixed to a bottle of wine; (c) "originating" when used in conjunction with the name of one of the Parties in respect of wine imported into the territory of the other Party means the wine has been produced in accordance with either Party's laws, regulations and requirements from grapes wholly obtained in the territory of the Party concerned; (d) "WTO Agreement" means the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization, done on 15 April 1994. -

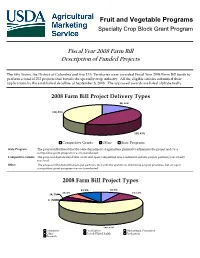

Fruit and Vegetable Programs Specialty Crop Block Grant Program

Fruit and Vegetable Programs Specialty Crop Block Grant Program Fiscal Year 2008 Farm Bill Description of Funded Projects The fifty States, the District of Columbia and five U.S. Territories were awarded Fiscal Year 2008 Farm Bill funds to perform a total of 252 projects that benefit the specialty crop industry. All the eligible entities submitted their applications by the established deadline of September 8, 2008. The approved awards are listed alphabetically. 2008 Farm Bill Project Delivery Types 36; 14% 108; 43% 108; 43% Competitive Grants Other State Programs State Program The proposal illustrated that the State department of agriculture planned to administer the project and/or a competitive grant program was not conducted. Competitive Grants The proposal demonstrated that a fair and open competition was conducted and the project partner(s) are clearly involved. Other The proposal illustrated that project partners met with the grantee to determine project priorities, but an open competitive grant program was not conducted. 2008 Farm Bill Project Types 24; 9% 19; 7% 15; 6% 27; 11% 14; 5% 2; 1% 156; 61% Education Food Safety Marketing & Promotion Other Pest & Plant Health Production Research Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries Amount Awarded: $125,779.00 Number of Projects: 2 • Assist Alabama specialty crop producers with direct marketing, value-added operations, consumer education, agritourism and general promotions. • Expand and target families in the undeserved counties in Alabama to conduct workshops to teach parents how to incorporate fresh produce as a staple in the family's diet. Alaska Division of Agriculture Amount Awarded: $101,521.00 Number of Projects: 2 • Increase outreach efforts to Alaskan specialty crop farmers who are not currently part of the Alaska Grown program and develop a newsletter to alert food service industry wholesalers of the availability of Alaska Grown specialty crops through the hiring of a project assistant. -

Aglianico from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Aglianico From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Aglianico (pronounced [aʎˈʎaːniko], roughly "ahl-YAH-nee- koe") is a black grape grown in the Basilicata and Campania Aglianico regions of Italy. The vine originated in Greece and was Grape (Vitis) brought to the south of Italy by Greek settlers. The name may be a corruption of vitis hellenica, Latin for "Greek vine."[1] Another etymology posits a corruption of Apulianicum, the Latin name for the whole of southern Italy in the time of ancient Rome. During this period, it was the principal grape of the famous Falernian wine, the Roman equivalent of a first-growth wine today. Contents Aglianico from Taurasi prior to veraison Color of Black 1 History berry skin 2 Relationship to other grapes Also called Gnanico, Agliatica, Ellenico, 3 Wine regions Ellanico and Uva Nera 3.1 Other regions Origin Greece 4 Viticulture Notable Taurasi, Aglianico del Vulture 5 Wine styles wines 6 Synonyms Hazards Peronospera 7 References History The vine is believed to have first been cultivated in Greece by the Phoceans from an ancestral vine that ampelographers have not yet identified. From Greece it was brought to Italy by settlers to Cumae near modern-day Pozzuoli, and from there spread to various points in the regions of Campania and Basilicata. While still grown in Italy, the original Greek plantings seem to have disappeared.[2] In ancient Rome, the grape was the principal component of the world's earliest first-growth wine, Falernian.[1] Ruins from the Greek Along with a white grape known as Greco (today grown as Greco di Tufo), the grape settlement of Cumae. -

Description of Funded Projects

Transportation and Marketing Specialty Crop Block Grant Program Fiscal Year 2013 Description of Funded Projects The fifty States, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. Territories were awarded Fiscal Year 2013 funds to perform a total of 695 projects that benefit the specialty crop industry. All the eligible entities with the exception the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands submitted their applications by the established deadline of July 10, 2013. The approved awards are listed alphabetically. 2013 Project Delivery Types 134; 19% 2; 0% 559; 81% Competitive Grants Other State Programs State Program The proposal illustrated that the State department of agriculture planned to administer the project and/or a competitive grant program was not conducted. Competitive Grants The proposal demonstrated that a fair and open competition was conducted and the project partner(s) are clearly involved. Other The proposal illustrated that project partners met with the grantee to determine project priorities, but an open competitive grant program was not conducted. 2013 Project Types 104; 15% 159; 23% 42; 6% 54; 8% 108; 16% 45; 6% 183; 26% Education Food Safety Marketing & Promotion Other Pest & Plant Health Production Research Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries Amount Awarded: $380,805.87 Number of Projects: 14 • Partner with the Alabama Cooperative Extension System (Talladega County) to increase small business opportunities for specialty crop producers by conducting workshops and demonstrations on -

T.D. ATF-370 Grape Variety Names for American Wines

522 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 5 / Monday, January 8, 1996 / Rules and Regulations Par. 5. In § 602.101, paragraph (c) is designations for American wines bottled FR 13623, March 31, 1982]. According amended by adding entries in numerical prior to January 1, 1997. Alternative to its charter, the Committee was to order to the table to read as follows: names listed at § 4.92(b) may be used as advise the Director of the grape varieties designations for American wines bottled and subvarieties which are used in the § 602.101 OMB Control numbers. prior to January 1, 1999. production of wine, to recommend * * * * * FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: appropriate label designations for these (c) * * * Charles N. Bacon, Wine, Beer, and varieties, and to recommend guidelines Spirits Regulations Branch, Bureau of for approval of names suggested for new Current OMB CFR part or section where control num- Alcohol, Tobacco and Forearms, 650 grape varieties. Their recommendations identified and described ber Massachusetts Avenue, NW, were restricted to grape names used in Washington, DC 20226; Telephone (202) the production of American wines. The 927±8230. Committee's final report, presented to ***** the Director in September 1984, 1.1221±2(d)(2)(iv) ................. 1545±1480 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: contained their findings regarding use of 1.1221±2(e)(5) ...................... 1545±1480 Background the most appropriate names for 1.1221±2(g)(5)(ii) .................. 1545±1480 domestic winegrapes varieties. ATF 1.1221±2(g)(6)(ii) .................. 1545±1480 The Federal Alcohol Administration Act 1.1221±2(g)(6)(iii) ................. 1545±1480 announced that the Committee's report Section 105(e) of the Federal Alcohol was available to the public in Notice No. -

Abruzzan Wine Cluster Advancement Through Trans-National Cooperation and Entrepreneurship

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2010 Hood Imports: Abruzzan Wine Cluster Advancement Through Trans-National Cooperation and Entrepreneurship Stewart Jennings Hood Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Hood, Stewart Jennings, "Hood Imports: Abruzzan Wine Cluster Advancement Through Trans-National Cooperation and Entrepreneurship" (2010). Honors Theses. 2029. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2029 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This success of this thesis could not have been accomplished without the help of countless individuals. 1 would like to thank John Samonds, Debra Young, William D'Alonzo, Angela Tumini, John Juergens, Michael Harvey, Luca and the entire Ciscato, Rossetti and D'Alonzo families, Raimondi Stefano, Maria D'Alessio, Guiseppe Cavaliere, Dirk Robertson, Fausto Emilio Albanesi, Emanuele Altieri, my friends and family, and all of the winemakers in Abruzzo, Italy. 1 would also like to thank Jim Barksdale for his generous contributions and fellowship grant, which made this whole project and travel to Italy possible. Lastly, I would like to give a special thanks to my advisor and mentor, Christian Sellar. Without his expertise and continuous patience and enthusiasm this paper would never have gotten off the ground. 11 ABSTRACT Hood Imports: Abruzzan Wine Cluster Advancement Through Trans-National Cooperation and Entrepreneurship [Under the Direction of Dr. -

Consuming Concerns

CONSUMING CONCERNS The 2013 State-by-State Report Card On Consumer Access To Wine Issued By The American Wine Consumer Coalition Washington, DC August 2013 INTRODUCTION The patchwork of state laws concerning wine and consumer access to wine products create a complex and difficult to understand legal quilt. This is due to the passage of the 21st Amendment to the Constitution in 1933 that not only ended the 15-year experiment with national alcohol Prohibition, but also gave primary responsibility to the states for the regulation of alcohol sales and consumption. The states took that responsibility seriously and enacted a variety of laws and regulations concerning how its residents could access and consume wine. Eighty years after passage of the 21st Amendment, many of the alcohol and wine-related laws put in place in the 1930s are still in place in most states, despite a cultural, economic and commercial reality that is starkly different from the 1930’s. In some cases, however, laws concerning how consumers may access wine products and use wine have been updated to match the economic changes that have occurred, to accommodate legal rulings that showed many of the earlier laws to be unconstitutional and to meet the demands of an American consumer base that has become fervently interested in the wines produced now in every state in the country as well as the thousands of imported wines that now reach American shores from Europe, South America, Canada, Eastern Europe, Africa, Australia, New Zealand and other spots on the globe. “Consuming Concerns: The 2013 State-by-State Report Card on Consumer Access to Wine” looks at how friendly the fifty states’ and District of Columbia’s wine laws are to its wine consumers. -

Get Ready for a Very Unexpected Taste of West Virginia

Get ready for a very unexpected taste of West Virginia. By Cele and Lynn Seldon ost people don't wines. Visitors can enjoy a think of West glass and picnic lunch on the Virginia when it gazebo overlooking the orig comes to wine inal 7th hole, take a self production. guided winery tour or pick However, the moqntainous their own blueberries in their terrain and cooler tempera three-acre blueberry patch. tures actually lend themselves A bit further north near well to the growing of a wide Summersville, Kirkwood variety of grapes in the Moun Winery is home to one of tain State. And that's led to a proliferation of grape growers West Virginia's finest wines, as well as the only locally-made and wine producers here over the past decade. bourbon whiskey at Isaiah Morgan Distillery. Although Kirk Today, the state hosts a total of 19 wineries, with 15 wood produces a few traditional reds and whites, the staples currently open to the public for tastings and tours - which among its 30-plus styles are fruit wines, like blackberry and includes several meaderies (a winery that produces honey blueberry. For something truly unique, try the Appalachian wines or meads) and winery I distillery combinations. strawberry-rhubarb, ramp onion or dandelion wines. Three appellations, more properly known as American On the western side of the state, Fisher Ridge Winery is Viticultural Areas, make up the wine regions: the Kanawha one of the West Virginia's oldest wineries and was started by River Valley, Ohio River Valley and the Shenandoah Valley.