US Election Note: International Trade Policy After 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hull Fa1nilies United States

Hull Fa1nilies • lll The United States By REV. WILLIAM E. HULL Copyright 1964 by WILLIAM E. HULL Printed by WOODBURN PRINTING CO - INC. Terre Haute, Indiana CONTENTS PAGE Appreciation ii Introduction ......................... ......... .................................... ...................... iii The Hon. Cordell Hull.......................................................................... 1 Hull Family of Yorkshire, England .................................................. 2 Hull Families of Somersetshire, England ........................................ 54 Hull Families of London, England ........... ........................................ 75 Richard Anderson Hull of New Jer;;ey .......................................... 81 Hull Families of Ireland ...................................................................... 87 Hull-Trowell Lines of Florida ............................................................ 91 William Hu:l Line of Kansas .............................................................. 94 James Hull Family of New Jersey.................................................... 95 William Hull Family of New Foundland ........................................ 97 Hulls Who Have Attained Prominence ............................................ 97 Rev. Wm. E. Hull Myrtle Altus Hull APPRECIATION The writing of this History of the Hull Families in the United States has been a labor of love, moved, we feel, by a justifiable pride in the several family lines whose influence has been a source of strength wherever families bearing -

Final Catalogue

Price Sub Price Qty. Seq. ISBN13 Title Author Category Year After Category USD Needed 70% 1 9780387257099 Accounting and Financial System Robert W. McGee, Barry University, Miami Shores, FL, USA; Galina Accounting Auditing 2006 125 38 Reform in Eastern Europe and Asia G. Preobragenskaya, Omsk State University, Omsk, Russia 2 9783540308010 Regulatory Risk and the Cost of Capital Burkhard Pedell, University of Stuttgart, Germany Accounting Auditing 2006 115 35 3 9780387265971 Economics of Accounting Peter Ove Christensen, University of Aarhus, Aarhus C, Denmark; Accounting Auditing 2005 149 45 Gerald Feltham, The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Commerce & Business Administration 4 9780387238470 Accounting and Financial System Robert W. McGee, Barry University, Miami Shores, FL, USA; Galina Accounting Auditing 2005 139 42 Reform in a Transition Economy: A G. Preobragenskaya, Omsk State University, Omsk, Russia Case Study of Russia 5 9783540408208 Business Intelligence Techniques Murugan Anandarajan, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Accounting Auditing 2004 145 44 Asokan Anandarajan, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ, USA; Cadambi A. Srinivasan, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA (Eds.) 6 9780387239323 Economics of Accounting Peter O. Christensen, University of Southern Denmark-Odense, Accounting Special 2003 85 25 Denmark; G.A. Feltham, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Topics BC, Canada 7 9781402072291 Economics of Accounting Peter O Christensen, University of Southern Denmark-Odense, Accounting Auditing 2002 185 56 Denmark; G.A. Feltham, Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 8 9780792376491 The Audit Committee: Performing Laura F. Spira Accounting Special 2002 175 53 Corporate Governance Topics 9 9781846280207 Adobe® Acrobat® and PDF for Tom Carson, New Economy Institute, Chattanooga, TN 37403, USA.; Architecture Design, 2006 85 25 Architecture, Engineering, and Donna L. -

6–30–10 Vol. 75 No. 125 Wednesday June 30, 2010 Pages 37707–37974

6–30–10 Wednesday Vol. 75 No. 125 June 30, 2010 Pages 37707–37974 VerDate Mar 15 2010 20:04 Jun 29, 2010 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\30JNWS.LOC 30JNWS emcdonald on DSK2BSOYB1PROD with NOTICES6 II Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 125 / Wednesday, June 30, 2010 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

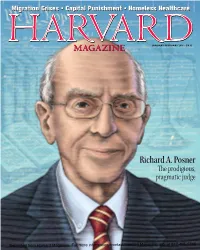

Richard A. Posner the Prodigious, Pragmatic Judge

Migration Crises • Capital Punishment • Homeless Healthcare january-february 2016 • $4.95 Richard A. Posner The prodigious, pragmatic judge Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 OnlyOnlyOnly onon on KiawahKiawah Kiawah Island.Island. Island. THETHETHE OCEANOCEAN OCEAN COURSECOURSE COURSE CASSIQUECASSIQUECASSIQUE ANDAND AND RIVERRIVERRIVER COURSECOURSE COURSE ANDAND AND BEACHBEACHBEACH CLUBCLUB CLUB SANCTUARYSANCTUARYSANCTUARY HOTELHOTEL HOTEL OCEANOCEANOCEAN PARKPARK PARK 201220122012 PGAPGA PGA CHAMPIONSHIPCHAMPIONSHIP CHAMPIONSHIP SPORTSSPORTSSPORTS PAVILIONPAVILION PAVILION FRESHFIELDSFRESHFIELDSFRESHFIELDS VILLAGEVILLAGE VILLAGE SASANQUASASANQUASASANQUA SPASPA SPA HISTORICHISTORICHISTORIC CHARLESTONCHARLESTON CHARLESTON KiawahKiawahKiawah IslandIsland Island hashas has beenbeen been namednamed named CondéCondé Condé NastNast Nast Traveler’sTraveler’s Traveler’s #1#1 #1 islandisland island inin in thethe the USAUSA USA (and(and (and #2#2 #2 inin in thethe the world)world) world) forforfor aa myriadmyriada myriad ofof of reasonsreasons reasons –– 10–10 10 milesmiles miles ofof of uncrowdeduncrowded uncrowded beach,beach, beach, iconiciconic iconic golfgolf golf andand and resort,resort, resort, thethe the allureallure allure ofof of nearbynearby nearby Charleston,Charleston, Charleston, KiawahIsland.comKiawahIsland.comKiawahIsland.com || 866.312.1791 866.312.1791| 866.312.1791 || 1 1| KiawahKiawah1 Kiawah IslandIsland Island ParkwayParkway Parkway || Kiawah Kiawah| Kiawah -

Spring 2011 Newsletter

Spring 2011 Newsletter USJLP Delegates Join Disaster A special message from Relief Efforts in Iwate Prefecture George Packard I want to send deepest condolences to all who have been affected by the events of March 11 and afterwards. It has been a time of terrible tragedy for our Japanese friends and deep concern on the part of millions of Americans who have been touched by these events. Our US-Japan Leadership network of Fellows, delegates and friends has generated a torrent of messages of concern and an extraordinary outpouring of sympathy and offers to help. If there is any silver lining to be found in all this, it is the reaffirmation of the value of our program, where Japanese and Americans have learned to communicate and share their deepest feelings with each other. We are determined to go forward, and we Laura Winthrop (11,12) surveys the devastation in Ofunato, Iwate. believe this summer's conference in Kyoto, She and Spencer Abbot (10,11) share their experiences working with the U.S. government and with volunteer NGOs to assist Japan Hiroshima and elsewhere will be more in this unprecedented time of need. (Story on page 2) important and meaningful than ever before. You will meet in this newsletter the delegates An Outpouring of Support from the for 2011 - arguably one of the strongest classes ever - and I am pleased to note that fully one USJLP Community half of the new faces on each side are women! Within an hour after news of the Tohoku earthquake hit the On behalf of our foundation's board, I send world, USJLPers were online sending messages of concern, warmest congratulations to all the Fellows support, and information over who have blazed the trail to this point. -

SIPA News Writer

SIPAnews spring 2000 / VOLUME XIiI NO.2 1 From the Dean Lisa Anderson reports back from a SIPA-sponsored conference in Mexico City. 2 Faculty Forum Mahmood Mamdani believes the stage is set for a new way of studying Africa. 3 Alumni Forum Diana Bruce Oosterveld (’97 MPA) helps New Yorkers gain access to Medicaid. 4 Dear SIPA Eddie Brown (’99 MIA) lives in the “worst place in the world” and loves it. 5 Faculty Profile Peter Danchin returns to South Africa to help shape post-apartheid Constitution. 6 Alumni pay debt of gratitude by donating their time and talents to SIPA. 8 EPD students travel to Kosovo to help former combatants launch new lives. 9 8 MIA Program News Race relations forum highlights SIPA’s first Diversity Week. 10 MPA Program News 12 Schoolwide News 13 14 Faculty News 16 Alumni News New Alumni Director Nancy Riedl urges grads to keep in touch. 22 Class Notes It was a virtuoso display of the breadth and sophistica- tion of SIPA’s capacities in policy analysis. From the Dean: Lisa Anderson SIPA’s Bond with Mexico: Qué Viva! very so often, something debate about policy among the schol- that “globalization” and “informal happens that epitomizes ars and practitioners from SIPA, economy” aren’t any easier to define in much of what makes my CIDE, and the worlds of public policy Spanish than in English? Or that the job irresistibly gratifying. in both New York and Mexico City. March presidential elections in Taiwan One of those moments Columbia contributed faculty and were closely followed in Mexico, as occurred at the end of practitioners -

The Next Chapter: President Obama's Second-Term Foreign Policy

The Next Chapter: President Obama’s Second-Term Foreign Policy Foreign Next Chapter: President Obama’s Second-Term The The Next Chapter: President Obama’s Second-Term Foreign Policy Edited by Xenia Dormandy January 2013 Edited by Xenia Dormandy Edited by Xenia Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration Number: 208223 The Next Chapter: President Obama’s Second-Term Foreign Policy Edited by Xenia Dormandy January 2013 © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2013 Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 86203 279 8 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: istockphoto.com Designed and typeset by Soapbox Communications Limited www.soapbox.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Latimer Trend and Co Ltd Contents About the Authors iv Acknowledgments vi About the Stavros Niarchos Foundation vii Executive Summary viii 1 Introduction 1 Xenia Dormandy 2 The Economy 7 Bruce Stokes 3 Trade 14 Joseph K. -

Future-Of-Bay-Area-Jobs.Pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special acknowledgement goes to Amy Nguyen (A.T. Kearney) for managing this study from start to finish. This study would not have been possible without Amy’s unwavering commitment and hard work. Special thanks are also due to Sean CONDUCTED BY: Randolph (Bay Area Economic Forum) for his significant contribution to the drafting A.T. Kearney of the final report. Praveen Madan Amy Nguyen In addition to the many individuals who shared their expertise in interviews for this Anna Leon report, the study sponsors wish to thank the following for their additional assistance, Rohit Dixit advice and comments: Simon Bell (A.T. Kearney Global Business Policy Council) Brad McMillen Andrea Bierce (A.T. Kearney), Liz Brown (Collaborative Economics), Katherine Cope Bob Brownstein (Working Partnerships USA), Jen-Chang Chou (Stanford Keith Pradhan University), Tim Connors (U.S. Venture Partners), Saurine Doshi (A.T. Kearney), Scott Koren Bob Duffy (A.T. Kearney and Bay Area Council), Diana Farrell (McKinsey Global Institute), Fred Furlong (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), Carl Guardino CORE STUDY ADVISORS: (Silicon Valley Manufacturing Group), Jon Haveman (Public Policy Institute of John Ciacchella California), Doug Henton (Collaborative Economics), John Holland (Winston Marguerite Gong Hancock Battalia International), Joe Hurd (UCLA-Andersen Forecast), Prakash Jothee Russell Hancock (Hewlett Packard), Philipp Jung (A.T. Kearney), Bruce Kern (Economic Sean Randolph Development Alliance for Business), Jim Koch (Santa Clara University), Bruce Klassen (A.T. Kearney), Bart Kocha (A.T. Kearney), Vas Kodali (A.T. Kearney), Cynthia A. Kroll (University of California, Berkeley), Steve Manacek (A.T. Kearney), Anita Manwani (Agilent Technologies), Lenny Mendonca (advisor), Dirk Michels (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart), Stanley Myers (SEMI), Mike Nevens (McKinsey & Company, retired), Nagi Palle (A.T. -

Norcal Running Review's Second Annual Photographic Competition

1978 (#74) THE NEW LDV. THE EVOLUTION OF THE REVOLUTION. When we built the original LD-1000, we threw away the book of traditional running shoe ideas, and started a revolution. It was a radically new shoe that combined our famous Waffle sole with a super-wide flared heel to give runners stability and traction like never before. Now comes an evolutionary shoe that grew out of the original revolution. The LDV For some runners, it will be a better shoe. Others will still want the original. We’ve reduced the flare of the heel. Opened the toe. And built the LDV on a vector last shaped to the natural axis of your foot to decrease over-pronation. The outer sole is made from tougher rubber with a new Waffle sole pattern that has stabilizers for longer wear. The new LDV We built it because we never stop working to build something better. A . m ^ . ... .,,, , It’s all part of the Nike theory A ¿ ^ 8 2 8 5 S°W . Nimbus Ave! Suite 115 of evolution. Nike Beaverton, Oregon 97005 Also available in Canada through Pacific Athletic Supplies Ltd., 2451 Beta Avenue, Burnaby. B.C., Canada V5C 5N1 Road Test: Formula I T O * PERFORMANCE: Special traction profile grooving of wedge provides a smooth, yet makes this shoe highly responsive. Extended positive ride. ROAD HOLDING: Perfect sole and racing spoiler stores up touch-down stability achieved through flared heel and energy and throws leg into longer stride at lift thick wedge. Special sole profile (developed off. Timesaving ghilly lacing makes for in collaboration with the Automobile Industry) quicker starts. -

^Lljllgp^ 1941

IN |Wffl \i° 3 ^lljllgp^ 3VW 1941 Fifth Publication of the Oswego Historical Society OSWEGO CITY LIBRARY 1941 Palladium-Times, Inc. Oswego, N. Y. Printers Os LIVING CHARTER MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY FREDERICK AUGUSTUS EMERICK Admitted July 10, 1896 JOHN DAUBY HIGGINS Admitted July 10, 1896 ELLIOTT BOSTICK MOTT Admitted July 10, 1896 PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE SOCIETY William Pierson Judson 1896-1901 Theodore Irwin, Sr. 1902 William Pierson Judson 1903-1910 Dr. Carrington Macfarlane 1911-1912 John D. Higgins 1913-1923 Dr. James G. Riggs 1924-1935 •Frederick W. Barnes 1936 Edwin M. Waterbury 1937-1941 *Vice-President acting as President. n CONTENTS Page LIVING CHARTER MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY II PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE SOCIETY II OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY, 1941 IV STANDING COMMITTEES, 1941 V NECROLOGY VI "LEST WE FORGET" VII WINTER PROGRAM, 1941-1942 VIII THREE GENERATIONS OF COOPERS IN OSWEGO (by Dr. Lida S. Penfield) 1-7 "UP TO ONTARIO," DIARY OF STEPHEN CROSS OF NEWBURYPORT, MASS., COMPILED IN 1756 (by Robert Macdonald) 8-18 THE RISE OF "THE FOURTH ESTATE" IN OSWEGO COUNTY (by Edwin M. Waterbury) 19-98 THE "VANDALIA," THE FIRST SCREW-PROPELLED VESSEL ON THE GREAT LAKES (by Herbert R. Lyons) 99-110 OLD HOMES OF OSWEGO—PART II (by Miss Anna Post) 111-118 TRAVEL IN EARLIER DAYS (by Joseph T. McCaffrey) 119-140 COMMODORE MELANCTHON TAYLOR WOOLSEY, LAKE ONTARIO HERO OF THE WAR OF 1812 (by Leon N. Brown) 141-152 8628S in LIST OF OFFICERS 1941 President Edwin M. Waterbury Vice-Presidents Frederick W. Barnes Ralph M. Faust Grove A. -

Spring 2009 Newsletter

Spring 2009 Newsletter USJLPers Attend the Inauguration of President Barack Obama In freezing cold temperatures amidst throngs of people, USJLPers traveled from far and wide on January 20, 2009 to witness one of the largest Presidential Inau- gurations in US history. Among performances by such artists as Aretha Franklin and Yo-Yo Ma, an Inaugural poem was read by Elizabeth Alexander (pictured at right; photo from elizabethalexander.net), sister of USJLP Fellow Mark Alexander (05, 06; pictured left), who met up with Mark Williams (04, 05) at the Root Ball. Jane Kang (05, 06), Ananda Martin (06, 07) and Doug Raymond (08) traveled from California, and Damon Porter (06) and Corey Dillon came from Missouri Elizabeth Alexander, to attend the festivities. sister of USJLPer Mark Alexander, read a poem at the Inauguration. Center: Jane Kang (05, 06) and Ananda Martin (06, 07) at Mark Williams (04, 05; left) and Mark the Huffington Post Alexander (05, 06; right) celebrate the Ball. Doug Inauguration at the Root Ball, January 20, Raymond (08) also 2009. Below: Damon Porter (06) and attended Corey Dillon at the Inaugural Ball Spring 2009 Haiku a cold winter day Obama rode winds of change our future awaits -Mark Alexander (05, 06) 1 Delegates to the 2009 Conference Japanese Delegates Kohei Muramatsu Assistant Manager, Toyota Motor Corporation, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo Nobumasa Akiyama Associate Professor, Hitotsubashi University, Mika Nabeshima Kunitachi, Tokyo Treasurer and Asst. to the Chief Executive Officer, TM Claims Service, Inc., Tokio Marine Mitsuru -

This Entire Document

OPEN IN SUNNYVALE 10-6 Weekdays; 'til 9 Thursdays & 10-5 Saturdays ADIDAS • BROOKS • CONVERSE • EATON • MITRE • NIKE • N E W BALANCE • PONY • PUMA • SAUCONY • TIGER Stop in and see our selection of GORE-TEX and ALL-WEATHER suits. We also have the Casio F-200, E.R.G., lots of top shoes and plenty of gift ideas (including gift certificates). SEE YOU AT THE RACES!! formerly Athletic department) THE RUNNING SHOP THAT WAS AROUND BERKELEY BEFORE THE BOOM! THE ONLY “NIKE ONLY” STORE (843-7767) WE ARE IN THE MIDST OF A CHANGE!! FOR TOO LONG THE ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT HAS BEEN CONFUSED WITH U.C. BERKELEY'S ATHLETIC OFFICE. WELL, THE NAME IS BEING CHANGED, WALLS ARE BEING PAINTED AND NEW CARPET IS ON THE WAY! WE'RE STILL THE RUN NING SHOP OF OLD BUT WITH A LITTLE SMOOTHER AP PEARANCE AND AN UNMISTAKEABLE NAME. SO COME IN 2114 Addison St., Berkeley AND SEE THE METAMORPHOSIS IN PROCESS. Hours: Mon-Fri. 10-6; Sat. 10-5 The 26 pound running shoe. Reebok engineered Designed for runners. forefoot flex reduces Our anatomically structured last resistance, ensuring conforms perfectly to follow smooth continuing the natural curve of the runner’s momentum. foot in motion. w m m m Non-skid outer sole combines durability, flexibility and Toe box is high and wide enough traction, permitting use on a to allow for natural toe spread. variety of surfaces. Ano{her Reebokfirst the This avoids blisters, broken toenails memory cushioned wedge and toe cramping. Reebok’s Patented Unit-II™ Sole. absorbs shock and eliminates bottoming out.