Migration, Regionalism, and the Ethnic Other, 1840-1870

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NÆRINGSPLAN LØTEN 2019-2030 Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Innledning

NÆRINGSPLAN LØTEN 2019-2030 Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Innledning ............................................... ................................................................... 3 1.1 Mandat ............................................................................................................................3 1.2 Historikk og resultater ....................................................................................................4 1.3 Føringer ...........................................................................................................................5 1.4 Arbeidsprosess og involvering .......................................................................................5 2 Utviklingstrekk og mulighetsrom .......... ................................................................... 6 2.1 Styrker og muligheter ......................................................................................................6 2.2 Utfordringer ......................................................................................................................7 2.3 Rammebetingelser .........................................................................................................7 2.4 Bærekraft ........................................................................................................................8 3 Mål og strategier .................................... .................................................................10 3.1 Kommunen som tilrettelegger ......................................................................................10 -

Kommunal Avløps- Og Slambehandling Sammenstilling Av Nøkkeltall, Utslipps- Og Driftsdata Årsrapport for 1998 Av Steinar 0Stlie - 3

Rapport nr. 5/1999 Kommunal avløps- og slambehandling Sammenstilling av nøkkeltall, utslipps- og driftsdata Årsrapport for 1998 av Steinar 0stlie - 3 - Innledning Årets rapportering på avløpssektoren er den første der kommunene i Hedmark har rapport elektronisk til fylkesmannen. Omleggingen har i hovedsak gått veldig bra, med noen få unntak. Kvaliteten på rapporteringen er også blitt stadig bedre. Det gjelder spesielt kommunenes rutiner for å frambringe økonomiske data, drifts data og utslippstall. Fylkesmannen har særlig anmodet kommunene om å fokusere på å framskaffe sikrere data for utslipp fra overløp og ledningsnett. Mange kommuner har nå installert utstyr og etablert rutiner for registrering av utslipp fra overløp på nettet. Når det gjelder lekkasjer og ukjente tap fra ledninger, varierer kommunenes oppgitte, relative tapstall svært mye. Måle- og beregningsusikkerhet må anses å være utilfredsstillende stor. Selve metodikken for vurdering og beregning av utslipp må også forbedres. Der data ikke er oppgitt fra kommunen, er ukjente tap er satt til 5 % av fosforproduksjonen, unntatt for helt nye ledningsnett, der tapsprosenten er satt til 2 %. Fylkesmannen vil oppfordre kommunene til å fastsette miljømål for lokale vannforekomster. God utslippsdokumentasjon er påkrevet for å følge opp disse målene, ildce minst er dette viktig med tanke på at det i relativt nær framtid kan være aktuelt å delegere mer myndighet til kommunene. I den sammenheng er det betenkelig at enkelte ildce synes å ha tilstreldcelig ressurser til å følge opp egne mål og statlige krav på avløpssektoren. 29 renseanlegg (38 %) har registrert en eller flere overskridelser av rensekrav for 1998, mot 32 anlegg (44 %) i 1997. Det er fortsatt parametrene Kl og K2 for total fosfor (tot-P) som har flest overskridelser, men nedgangen er samtidig også mest markant for disse parametrene (hhv. -

Volume 25, No

VOLUME 34, NO. 2 March 2014 http://vipclubmn.org FUTURE EVENT CALENDAR March 5 10:00 AM Board Meeting UNISYS, Eagan March 12 7:00 PM Social hour and speaker UNISYS, Eagan April 2 10:00 AM Board Meeting UNISYS, Roseville April 16 9:00 AM FREE Volunteer Breakfast VFW, Roseville May 7 10:00 AM Board Meeting UNISYS, Eagan May 14 7:00 PM Social hour and speaker UNISYS, Eagan MARCH PROGRAM: APRIL PROGRAM: Organic Farming Cooperatives Volunteer Recognition Breakfast March 12th, 7 PM - at the UNISYS, Eagan Visitors’ April 16th, 9:00 AM – The VIP Club will host the conference room. Preston Green is our invited speaker. annual Recognition Breakfast at the Roseville VFW for Mr. Green grew up on an Organic Valley Farm. Since Club members who performed volunteer services in 1992 his family has farmed the land organically and 2013. [Please review the “Volunteer Breakfast takes a certain pride in doing so. His family has since Schedule and 2013 Survey Form” on Pages 6 & 7 or moved to Virginia and is farming with the same on-line at http://vipclubmn.org/volunteer.html.] principles there as they did in Southwest Wisconsin. April is National Volunteer Month; our Breakfast Being a part of the Farmer-Owned Cooperative allows honors all VIP Club members who perform volunteer his family and many others access to a market place services wherever they reside. Last year, the 101 VIP that individually the over 1800 farmers would not have Club members who responded to our 2012 Survey, the opportunity to enjoy. donated over 21,000 hours to various organizations in Organic Valley and CROPP Cooperative is governed Minnesota, Arizona, Illinois, Texas, and Wisconsin. -

Directory of Nonprofit Organizations of Color in Minnesota

Directory of Nonprofit Organizations of Color in Minnesota edited by Michael D. Greco Fifth Edition January 2005 Center for Urban and Regional Affairs A publication of the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA), an all- University applied research and technical assistance center at the University of Minnesota that connects faculty and students with community organizations and public institutions working on significant public policy issues in Minnesota. The content of this publication is the responsibility of the author and is not necessarily endorsed by CURA or the University of Minnesota. © 2005 by The Regents of the University of Minnesota. This publication may be reproduced in its entirety (except photographs or other materials reprinted here with permission from other sources) in print or electronic form, for noncommercial educational and nonprofit use only, provided that two copies of the resulting publication are sent to the CURA editor at the address below and that the following acknowledgement is included: “Reprinted with permission of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA).” For information regarding commercial reprints or reproduction of portions of this publication, contact the CURA editor at the address below. Publication No. CURA 05-1 (1500 copies) This publication is available in alternate formats upon request. Cover art by Pat Rouse Printed with agribased inks on recycled paper with a minimum of 20% postconsumer waste. Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) University of Minnesota 330 HHH Center 301—19th Avenue South Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 phone: 612-625-1551 fax: 612-626-0273 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.cura.umn.edu The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, disability, public assistance status, veteran status, or sexual orientation. -

Biofokus-Rapport 2017-6 Biofokus Har På Oppdrag Fra Fylkes- Mannen I Hedmark Kvalitetssikret Naturtypelokaliteter I Skog I Et Utvalg Kommuner I Hedmark

Ekstrakt BioFokus-rapport 2017-6 BioFokus har på oppdrag fra Fylkes- mannen i Hedmark kvalitetssikret naturtypelokaliteter i skog i et utvalg kommuner i Hedmark. Totalt 30 Tittel naturtypelokaliteter presenteres i Kvalitetssikring av naturtypelokaliteter i skog i Hedmark 2016 denne rapporten og de aller fleste er kvalitetssikrede lokaliteter. Disse fordeler seg på 4 lokaliteter med A- verdi, 13 med B-verdi og 8 med C- Forfatter verdi. Blant de 30 lokalitetene er det Øivind Gammelmo gammel barskog som forekommer vanligst. Dato 24.02.2017 Antall sider Nøkkelord 27 sider inkl. vedlegg Hedmark Stange Sør-Odal Publiseringstype Nord-Odal Digitalt dokument (PDF). Som digitalt dokument inneholder denne Åsnes rapporten «levende» linker. Verdivurdering Naturtypekartlegging Skog Oppdragsgiver Kvalitetssikring Fylkesmannen i Hedmark Tilgjengelighet Dokumentet er offentlig tilgjengelig. Andre BioFokus rapporter kan lastes ned fra: Omslag http://biolitt.BioFokus.no/rapporter/Litteratur.htm FORSIDEBILDER Øvre: Traktkantarell. Midtre: Gammel granskog ved Middags-berget. Nedre: Oversiktsbilde fra Grasberget og Rapporten refereres som: vestover. Alle bilder er tatt av Øivind Gammelmo, Ø. 2017. Kvalitetssikring av naturtypelokaliteter i skog i Gammelmo. Hedmark 2016. BioFokus-rapport 6. ISBN 978-82-8209-571-6. Stiftelsen BioFokus. Oslo LAYOUT (OMSLAG) Blindheim Grafisk ISSN: 1504-6370 BioFokus: Gaustadalléen 21, 0349 OSLO ISBN: 978-82-8209-571-6 Telefon 99550257 E-post: [email protected] Web: www.biofokus.no 2 Forord BioFokus har på oppdrag fra Fylkesmannen i Hedmark kvalitetssikret et utvalg av tidlegere kartlagte naturtyper i skog i kommunene Stange, Sør-Odal Nord-Odal og Åsnes. Jan Schrøder har vært vår kontaktperson hos oppdragsgiver. Øivind Gammelmo har vært prosjektleder hos BioFokus. Denne rapporten har som mål å kort oppsummere resultatene fra kartlegginga i 2016. -

A Directory of Nonprofit Organizations of Color in Minnesota

A Directory of Nonprofit Organizations of Color in Minnesota Fourth Edition September 2001 A Directory of Nonprofit Organizations of Color in Minnesota Fourth Edition September 2001 A publication of the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, an independent applied research and technology center that connects University of Minnesota faculty and students with community organizations and public institutions working on significant public policy issues in Minnesota. The content of this report is the responsibility of the author, and is not necessarily endorsed by CURA. 2001 Publication No. CURA 01-13 (2500 copies) This report is not copyrighted. Permission is granted for reproduction of all or part of this publication, except photographs or other materials reprinted with permission from other sources. Acknowledgement, however, would be appreciated, and CURA would like to receive two copies of any publication thus reproduced. Please send materials to the attention of "CURA editor" at the address below. Cover art by Pat Rouse This publication is available in alternate formats upon request. Printed with agribased inks on recycled paper with minimum 20% post- consumer waste. Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) University of Minnesota 330 HHH Center 301 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 Phone: (612) 625-1551 Fax: (612) 626-0273 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.cura.umn.edu The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, disability, public assistance status, veteran status, or sexual orientation. -

Meet Seattle's Skål-Worthy Akevitt

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Neighborhood Arts CLU honors The Norwegians « Men først en kaffe og avis farmer i morgenstundens stille bris. » tickles D.C. Read more on page 13 – Per Larsen Read more on page 15 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 126 No. 14 April 17, 2015 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $2.00 per copy Meet Seattle’s skål-worthy akevitt Story on page 8 What’s inside? News 2-3 Brooklyn revs up for Syttende Mai Business 4 VICTORIA HOFMO The second event has been a tradition theme and a journal. This year’s pin design Sports 5 Brooklyn, N.Y. since the parade’s inception: the Church Ral- is very elegant; a golden cross between two Opinion 6-7 ly. This year will be especially meaningful, axes on a crimson background, the shield of Taste of Norway 8 Brooklyn is revving up for its annual as the parade’s theme is “Celebrating 1,000 the Christian church of Norway, which was Travel 9 Norwegian Constitution Day Parade, to be Years of Christianity.” The rally will be held founded under King Olaf during the 1030s. held on Sunday, May 17. One interesting on Saturday, May 2, at the Norwegian Chris- The journal does more than raise funds Roots & Connections 10 change that has occurred at Brooklyn’s pa- tian Home, beginning at 6:30 p.m. The guest through advertising. It has meaty content: an Obituaries & Religion 11 rade is that an increasing number of specta- speaker is Doug Thuen from Sparta Evan- essay about the theme, messages from dig- In Your Neighborhood 12-13 tors and participants come from Norway to gelical Free Church, New Jersey. -

Kartlegging Av Virksomheter Og Næringsområder I Mjøsbyen Mars 2019

Foto: Magne Vikøren/Moelven Våler Kartlegging av virksomheter og næringsområder i Mjøsbyen Mars 2019 FORORD Rapporten er i hovedsak utarbeidet av Marthe Vaseng Arntsen og Celine Bjørnstad Rud i Statens vegvesen. Paul H. Berger i Mjøsbysekretariatet har vært kontaktperson for oppdraget. Aktørene i prosjektgruppa for Mjøsbysamarbeidet har bidratt med innspill og kvalitetssikring. Data er innhentet og bearbeidet av Ingar Skogli med flere og rekkeviddeanalyser med ATP- modellen er utført av Hilde Sandbo, alle fra Geodataseksjonen i Statens vegvesen Region øst. Mars 2019 2 Innhold 1. Innledning og bakgrunn .................................................................................................... 4 2. Befolkningssammensetning i Mjøsbyen ............................................................................ 4 2.1 Befolkningsutvikling ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Pendlingsforhold og sysselsatte ................................................................................... 8 3 Metode – «Rett virksomhet på rett sted» ........................................................................... 14 3.1 ABC-metoden ............................................................................................................. 14 3.2 Kriteriesett for Mjøsbyen ............................................................................................ 15 3.2.1 Virksomhetene .................................................................................................... -

Restrained Eating

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 125 Restrained Eating Development and Models of Prediction in Girls BY KATARINA LUNNER ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 !"# $ % $ $ & ' ( )(' * +' ' , - %' $ & ' . ' "#' # ' ' /)01 "2##32#442# 0 % % % % % % ( % %' + (% 5 $ $ % %% ( $ $$ ' $ ( % $ % $ $ $ % %' $ 2 % 6 % 2 % % % % 78 "" " "# 9' ) / 5 ( % ( % ":"3 :" ' / ) // 0 / 70/9 (% 2 % $ $ % % )( % ; . % 8 ;' <% 2 % ( 0/ $ ' ) /// % 0/ (% 2 % $ 8:"" % % % ":"3 ' ) /= $ % 0/ (% 2 % $ % % % ' / ( $ % 5 $ $ % % %' % % % 2 % ! " # $ %&'()*+ > + * /))1 ;283 /)01 "2##32#442# ! !!! 283 7 !?? '5'? @ A ! !!! 2839 Sammanfattning Om en flicka har provat att banta, väger mer än normalt för sin ålder, har blivit retad för sitt utseende och är missnöjd med sin kropp är hon i riskzonen för att etablera problemfyllda ätbeteenden i tonåren. Delstudierna baseras på data från ett flerårigt projekt som följt flickor som vid studiens början var i åldrarna 7, 9, 11, 13, och 15 år. I studie I ökade andelen flickor som önskade att de var smalare mest -

Problem and Promise: Scientific Experts and the Mixed-Blood in the Modern U.S., 1870-1970

PROBLEM AND PROMISE: SCIENTIFIC EXPERTS AND THE MIXED-BLOOD IN THE MODERN U.S., 1870-1970 By Michell Chresfield Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Sarah Igo, Ph.D. Daniel Sharfstein, J.D. Arleen Tuchman, Ph.D. Daniel Usner, Ph.D. Copyright © 2016 by Michell Chresfield All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the result of many years of hard work and sacrifice, only some of which was my own. First and foremost I’d like to thank my parents, including my “bonus mom,” for encouraging my love of learning and for providing me with every opportunity to pursue my education. Although school has taken me far away from you, I am forever grateful for your patience, understanding, and love. My most heartfelt thanks also go to my advisor, Sarah Igo. I could not have asked for a more patient, encouraging, and thoughtful advisor. Her incisive comments, generous feedback, and gentle spirit have served as my guideposts through one of the most challenging endeavors of my life. I am so fortunate to have had the opportunity to grow as a scholar under her tutelage. I’d also like to thank my dissertation committee members: Arleen Tuchman, Daniel Sharfstein, and Daniel Usner for their thoughtful comments and support throughout the writing process. I’d especially like to thank Arleen Tuchman for her many pep talks, interventions, and earnest feedback; they made all the difference. I’d be remiss if I didn’t also thank my mentors from Notre Dame who first pushed me towards a life of the mind. -

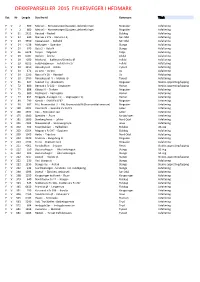

Dekkeparseller 2015 Fylkesveger I Hedmark

DEKKEPARSELLER 2015 FYLKESVEGER I HEDMARK Kat Nr Lengde Sted fra-til Kommune Tiltak F V 2 560 Mesnali - Norsetervegen/Sjusjøen, delstrekninger Ringsaker Asfaltering F V 2 660 Mesnali - Norsetervegen/Sjusjøen, delstrekninger Ringsaker Asfaltering F V 21 2421 Harstad - Rastad Eidskog Asfaltering F V 24 630 Skarnes x 175 - Korsmo r.kj. Sør Odal Asfaltering F V 24 3950 Veggarasjen - Delbekk Sør Odal Asfaltering F V 24 4138 Malungen - Sjøenden Stange Asfaltering F V 24 670 Gata S - Gata N Stange Asfaltering F V 26 6678 Torpet - Tolgensli Tolga Asfaltering F V 29 6187 Gjelten - Årleite Alvdal Asfaltering F V 29 7200 Moskaret - Kjøllmoen/Grimsbu Ø Folldal Asfaltering F V 29 8323 Foldshaugmoen - Folldal x Fv 27 Folldal Asfaltering F V 30 3450 Røroskrysset - Baklia Tynset Asfaltering F V 30 472 Os vest - Os bru Os Asfaltering F V 30 1100 Nøra x Fv 26 - Høystad Os Asfaltering F V 30 1700 Røroskrysset V - Motrøa Ø Tynset Asfaltering F V 51 407 Svestad r.kj. - Øverkvern Ringsaker Stedvis oppretting/lapping F V 72 800 Børstad x Fv 222 - Vangbanen Hamar Stedvis oppretting/lapping F V 72 888 Kåtorp N - Trafoen Ringsaker Asfaltering F V 75 600 Posthuset - Vestregate. Hamar Asfaltering F V 77 852 Ringgata, Aluvegen r.kj. - Vognvegen r.kj. Hamar Asfaltering F V 89 790 Kjendli - SANDEN XF67 Ringsaker Asfaltering F V 90 697 R.kj. Brumunddal S - Rkj. Brumunddal N (Brumunddal sentrum) Ringsaker Asfaltering F V 158 2502 Ånestad N - Heimdal V x Fv115 Løten Asfaltering F V 166 2691 Vea - Rokosjøen sag Løten Asfaltering F V 175 1840 Spetalen - Åsum Kongsvinger -

The Hyphenated Norwegian

VESTERHEIM IN RED, WHITE AND BLUE: THE HYPHENATED NORWEGIAN- AMERICAN AND REGIONAL IDENTITY IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, 1890-1950 By HANS-PETTER GRAV A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of History MAY 2018 © Copyright by HANS-PETTER GRAV, 2018 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by HANS-PETTER GRAV, 2018 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of HANS-PETTER GRAV find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. LAURIE MERCIER, Ph.D., Chair ROBERT BAUMAN, Ph.D. JEFFREY SANDERS, Ph.D. LUZ MARIA GORDILLO, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been many years in the making. It all began in 2004 at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington. Chandra Manning, Gina Hames, Carlton Benson, and Beth Kraig instilled in me a desire to pursue history as a profession. I completed a second major in history during the course of one academic year, and I do not believe I could have done it that quickly without the encouragement of Chuck Nelson and David Gerry at the Office of International Student Services. Important during my time at PLU was also the support of Helen Rogers, a close friend and an experienced history major. While my interest in Norwegian Americans’ relationship with Norway and Norwegian culture began during my time at PLU, it was during my years pursuing a Master’s degree at Montana State University in Bozeman that this project began to take shape.