Writing Poetry in Scots (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

11-20 November Issue

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs 11-20 November Issue St. Andrew deeming himself unworthy to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus Christ. Instead, he was nailed St. Andrew has been celebrated upon an X-shaped cross on 30 November 60AD in in Scotland for over a thousand years, Greece, and thus the diagonal cross of the saltire with feasts being held in his honour as was adopted as his symbol, and the last day in far back as the year 1000 AD. November designated his saint day. However, it wasn’t until 1320, According to legend, Óengus II, king of Picts when Scotland’s independence was and Scots, led an army against the Angles, a declared with the signing of The Germanic people that invaded Britain. The Scots Declaration of Arbroath, that he officially became were heavily outnumbered, and Óengus prayed the Scotland’s patron saint. Since then St Andrew has night before battle, vowing to name St. Andrew the become tied up in so much of Scotland. The flag of patron saint of Scotland if they won. Scotland, the St. Andrew’s Cross, was chosen in honour of him. Also, the ancient town of St Andrews On the day of the battle, white clouds formed was named due to its claim of being the final resting an X in the sky. The clouds were thought to place of St. Andrew. represent the X-shaped cross where St. Andrew was crucified. The troops were inspired by the apparent According to Christian teachings, Saint Andrew divine intervention, and they came out victorious was one of Jesus Christ’s twelve disciples. -

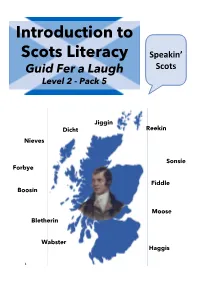

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution during Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants’ needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scots Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scots Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, shortbread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

Allan Ramsay's Poetic Language of Anglo-Scottish Rapprochement

Études écossaises 17 | 2015 La poésie écossaise Allan Ramsay’s Poetic Language of Anglo-Scottish Rapprochement Allan Ramsay et le langage du rapprochement anglo-écossais Michael Murphy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/919 DOI: 10.4000/etudesecossaises.919 ISSN: 1969-6337 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version Date of publication: 25 April 2015 Number of pages: 13-30 ISBN: 978-2-84310-296-7 ISSN: 1240-1439 Electronic reference Michael Murphy, “Allan Ramsay’s Poetic Language of Anglo-Scottish Rapprochement”, Études écossaises [Online], 17 | 2015, Online since 25 April 2016, connection on 15 March 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/919 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.919 © Études écossaises Michael Murphy Université du Littoral Côte d’Opale Allan Ramsay’s Poetic Language of Anglo-Scottish Rapprochement Ramsay (1684?–1758), one of the last generation born in an independent Scottish state, was also part of the first generation of Hanoverian Britons; his career began just after the Treaty of Union of 1707. There is a polit- ical tension in his writings: until the 1730s at least he hoped for the resto- ration of an independent, Stuart, Scottish kingdom, but he also worked for Anglo-Scottish reconciliation. The latter was neither a premedit- ated project on his part, nor direct support of the Hanoverian dynasty, their governments, or the terms of the Treaty of Union. It was a slow movement, measured notably through epistolary poems exchanged with Englishmen. These personal, literary contacts helped him to imagine a common future shared by two peoples, or more precisely their elites. -

Linguistic and Political Backlash and Conformity in Eighteenth-Century Scots

1 ‘An Eye for an Aye’: Linguistic and Political Backlash and Conformity in Eighteenth-Century Scots LING690 Sarah van Eyndhoven Abstract This study examines the effects of social and political changes that were occurring during the eighteenth century in Scotland on the use of written Scots, focussing in particular upon authors who were known to have been for or against the Union of the Parliaments in 1707. In order to capture a holistic representation of the levels of Scots in writing, I explore the proportion of Scots lexemes, compared with their corresponding English lexemes, in a purpose-built corpus containing a range of eighteenth-century texts. This corpus contains both texts that were produced by a general cross- section of Scottish society, and a number of politically-active individuals. I take a quantitative sociolinguistic approach to historical data by utilising statistical techniques that examine linguistic variation in a data-driven manner. This enables a more detailed and empirical exploration of Scots in the eighteenth century, which until now has been largely examined on a descriptive basis only. Using a number of statistical tools that are well suited to historical analyses, such as Variability-based Neighbour Clustering (Gries & Hilpert, 2008), conditional inference trees (Hothorn et al., 2006) and random forests (Breiman, 2001), I have been able to reconstruct both the general patterning of the Scots language over time and the extralinguistic factors encouraging or suppressing its presence in writing. In particular, I compare the use of Scots between the general literate population and political individuals active during this time period. I also explore the effect of the latter’s political sympathies on their language choices, and uncover several new and interesting effects conditioning the levels of Scots in their writings. -

Sib Folh Flews

jii^^; Sib Folh flews 5 R 09 5 3 2. S. t* | a cu 01 8 he Earl of Wessex leaving alter the Official Opening of the Orkney Library Tand Archive on Tuesday 2nd September 2003. In this lovely building Orkney Family history Society is to have its new office. J Contents:- V 2 From the Chair. Future Events 8 Rev. Alexander Smith 3 From the Editor. Deadlines. 10 Website information September meeting 11 Working on the Gardens' 4 The Long Road T)ome. Directory 12 Photographic history o! Flotta 5 Official opening of Orkney Library 13 October meeting & Archive 15 ftiuiualTHeal 6 Booh Review 16 Research via the Internet Quiz 19 Robert Snhster r From the Chair Seven years later my successor has been found! At the moment I am enjoying reading yet another new Orkney Book that has ap- At the last committee meeting Anne Ren- peared in time for Christmas. It is "'The dall was appointed Vice-Chairman and Shore' and roond aboot" written by the accepted the post with the knowledge that retired Orkney Librarian, David Tinch. she would soon be Chairman. This is a In it he describes growing up in Kirk- popular appointment Anne has taken an wall in the thirties and forties and all in active part in the running of the society a very humorous style. It contains in- from the early days. Among other things teresting photographs including school she has transcribed censuses, is working groups and a major bonus is the forty- on the Old Parish Registers and looks three prints of his stunning oil paint- after the office most Saturday afternoons. -

The Heritage of Burns

1 fyxmll ^nxvmity fptag BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henry W. Sage 1891 ..^..Z.Z.f.Z.fS, 2r.7/M0?., 6896- The date shows when this volume was takert. call and give to To renew this book copy the No. "™J the librarian, u HOME USE RULES. > All Books subject to Recall. Books not used for instruction or research , jwr§4 are returnable within ' 4 weeks. Volumes of periodi- cals and of pamphlets are held? in the library as much as possible. For special purposes they .are given out for a lymited time. ^Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the bene- fit of other persons. Books not needed during recess periods should be returned to the library, or arrange- ments made for their return during borrow- er's absence, if wanted. ^ -tean Books needed by '• more than one person are held on the reserve .v*R^ list. Books of special value and gift books, when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to report all cases of books marked or muti- lated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. Cornell University Library PR4331.T94 The heritage of Burns. 3 1924 013 447 630 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013447630 THE HERITAGE OF BURNS Thro' busiest street and loneliest glen Are felt theflaslies of his pen : He rules, 'midwinter snows, and when Beesfill their hives ; Deep in the genial heart of men His power survives. -

Britishness and Problems of Authenticity in Post-Union Literature from Addison to Macpherson

"Where are the originals?" Britishness and problems of authenticity in post-Union literature from Addison to Macpherson. Melvin Eugene Kersey III Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Leeds, School of English September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the generous help, encouragement and support of many people. My research has benefited beyond reckoning from the supervision of Professor David Fairer, whose inspired scholarship has never interfered with his commitment to my research. It is difficult to know whether to thank or to curse Professor Andrew Wawn for introducing me to James Macpherson's Ossianic poetry during my MA at Leeds, but at any rate I am now doubly indebted to him for his insightful reading of a chapter of this thesis. I am also grateful to Professor Paul Hammond for his enormously helpful comments and suggestions on another chapter. And despite the necessary professional distance which an internal examiner must maintain, I have still enjoyed the benevolent proximity effect of Professor Edward Larrissy. I am grateful to Sue Baker and the administrative staff of the School of English for providing me with employment and moral support during this thesis, especially Pamela Rhodes. Special thanks to the inestimable help, friendship and rigorous mind of Dr. Michael Brown, and to Professor Terence and Sue Brown for their repeated generous hospitality in Dublin. -

U) ( \ ' Jf ( V \ ./ R *! Rj R I < F} 5 7 > | \ F * ( I | 1 < T M T 51 I 11 Ffi O [ ./: I1 T I'lloiiriv

U) ( \ ' Jf (\ ./v r *! r r ji < f} 5 7 > | \ f * ( i | 1 < t mt 51 i 11 ffi O [ ./: 1 t I I'llOiiriv '^y ■ ■; '/ k :}Kiy, ■ 7iK > v | National Library of Scotland illllllllllllllllllllillllllli *6000536714* Hfl2'2l3'D'/3gg' SCS.SH55. 511^54- SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FIFTH SERIES VOLUME 19 Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633 Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633 t John Durkan Edited and revised by Jamie Reid-Baxter SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY 2006 THE BOYDELL PRESS © Scottish History Society 2013 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2013 A Scottish History Society publication in association with The Boydell Press an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620-2731, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN 978-0-906245-28-6 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Papers used by Boydell & Brewer Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in -

Scottish Literature

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 30 | Issue 1 Article 1 1-1-1998 Volume 30 Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation (1998) "Volume 30," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 30: Iss. 1. Available at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol30/iss1/1 This Full Volume is brought to you for free and open access by the USC Columbia at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studies in Scottish Literature Editorial Board Ian Campbell David Daiches Robert L. Kindrick A. M. Kinghorn Walter Scheps Rodger L. Tarr Hugh MacDiarmid (member, founding Editorial Board) VOLUME XXX Studies in Scottish Literature Edited by G. Ross Roy Associate Editor Lucie Roy Department of English University of South Carolina Columbia, South Carolina © 1998 G. Ross Roy Illustrations copyrighted by Alasdair Gray Printed in the United States of America ISSN: 0039-3770 ADDRESS ALL CORRESPONDENCE TO: Editor, Studies in Scottish Literature Department of English University of South Carolina Columbia, South Carolina 29208 (USA) Keying and formatting of text Sej Harman Por Lucie ~y a 6rave CittCe soUier Table of Contents Preface......................................................................................................... xi Burns in Beirut Tom Sutherland ................................................................................. -

Form Dictionary

POETIC FORMS Acrostic: Alcaics: Quatrain: 11 syllables, 11 syllables, 9 syllables, 10 syllables. Dactylic. Alexandrine: Iambic Hexameter. Alliterative Metre: 'Bring me my bow of burning gold' ( aa / ab ). The first three stressed syllables are alliterated, the fourth stress isn't. There is an implied cesura between the first two stresses and the second two. Other alliterative patterns include ab/ ab and ab / ba Cynghanedd would also seem to be employed. Ballad metre: Quatrain with the rhyme scheme: abcb. 4 stresses, 3 stresses, 4 stresses, 3 stresses. Ballade: Rhyme scheme: ababbcbc, with an envoi: bcbc. This form has a refrain repeated in the last line of each stanza. Blank verse: Unrhymed iambic petametre. Burns stanza: Rhyme scheme: aaabab. 4 stresses, 4 stresses, 4 stresses. 2 stresses, 4 stresses, 2 stresses. Chant royal: Rhyme scheme: ababccddede, with an envoi: ddede. Last line of the stanza is repeated as a refrain. Clerihew: common measure: Rhyme scheme: abab. 4 stresses, 3 stresses, 4 stresses, 3 stresses. Curtal sonnet: G M Hopkins shortened the sonnet to 10 and a half lines. Cyhydedd Fer: Rhyme scheme aa.... 8 syllables a line. Cyhydedd Naw Ban: As above, but with 9 syllables per line. Cynghanedd Draws: Mae ynom / bawb ddymuniad. Not all of the consonants of the first hemistich are repeated in the second. This line has two primary stresses. Cynghanedd Groes: Darn o'r haul / draw yn rhywle. All of the consonants of the first hemistich are answered in the second hemistich. This line has two primary stresses. Cynghanedd Lusg: Yn llawen / mewn llwyn ir. The last syllable of the first hemistich rhymes with the penultimate syllable of the last hemistich.