The Ontological Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

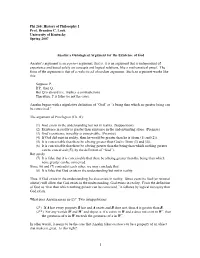

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

The Philosophy of Religion Contents

The Philosophy of Religion Course notes by Richard Baron This document is available at www.rbphilo.com/coursenotes Contents Page Introduction to the philosophy of religion 2 Can we show that God exists? 3 Can we show that God does not exist? 6 If there is a God, why do bad things happen to good people? 8 Should we approach religious claims like other factual claims? 10 Is being religious a matter of believing certain factual claims? 13 Is religion a good basis for ethics? 14 1 Introduction to the philosophy of religion Why study the philosophy of religion? If you are religious: to deepen your understanding of your religion; to help you to apply your religion to real-life problems. Whether or not you are religious: to understand important strands in our cultural history; to understand one of the foundations of modern ethical debate; to see the origins of types of philosophical argument that get used elsewhere. The scope of the subject We shall focus on the philosophy of religions like Christianity, Islam and Judaism. Other religions can be quite different in nature, and can raise different questions. The questions in the contents list indicate the scope of the subject. Reading You do not need to do extra reading, but if you would like to do so, you could try either one of these two books: Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford University Press, third edition, 2003. Chad Meister, Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Routledge, 2009. 2 Can we show that God exists? What sorts of demonstration are there? Proofs in the strict sense: logical and mathematical proof Demonstrations based on external evidence Demonstrations based on inner experience How strong are these different sorts of demonstration? Which ones could other people reject, and on what grounds? What sort of thing could have its existence shown in each of these ways? What might we want to show? That God exists That it is reasonable to believe that God exists The ontological argument Greek onta, things that exist. -

Ontological Arguments

Ontological Arguments According to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would be an argument that established the existence of God using nothing more than the resources of logical reasoning. That is, according to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would be an argument that had nothing but truths of logic—i.e. truths that can be known a priori by any reasonable cognitive agent—for its premises, and reached the conclusion that God exists using nothing but logically impeccable inferences from those premises. Hence, according to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would show that there is a sense in which it is a logical theorem—a truth provable a priori by any reasonable cognitive agent—that God exists. Given this common philosophical understanding, we can say that the aim of those who put forward what they call “ontological arguments” is to show that, merely in virtue of being reasonable in the formation of beliefs that it holds on the basis of reason alone, any reasonable cognitive agent holds beliefs that jointly entail that God exists. Moreover, we can observe that a successful ontological argument will be such that none of its premises can be reasonably rejected by a reasonable cognitive agent; and it will be such that no reasonable being can reasonably deny that the conclusion of the argument is entailed by the premises of the argument; and it will have the conclusion that God exists. The last claim in the previous paragraph is not exactly right. Many so-called “ontological arguments” do not end with the words “Therefore God exists”. -

The Primacy of Faith and the Priority of Reason: a Justification for Public Recognition of Revealed Truth

The Primacy of Faith and the Priority of Reason: A Justification for Public Recognition of Revealed Truth Fr. David Pignato St. John’s Seminary, Brighton, MA The Catholic tradition of the primacy of faith, as taught by both Augustine and Anselm, is not an endorsement of fideism, but rather a rule of respecting the supra-rational nature of divinely revealed truths that must be accepted by faith. The same tradition upholds the priority of unaided reason, which can confirm the truth of faith by examining the evidence of revelation, or the motives of credibility. This critical role of reason justifies the individual assent of faith and also offers a basis upon which a secular state, reliant on reason, could conceivably refer to revealed truths, to help it discover the objective moral principles that aid the state in its effort to promote human dignity and the common good. Credo ut intelligam “Credo ut intelligam.” Perhaps second only to “Cur Deus Homo,” no other words come to mind more quickly at the mention of St. Anselm than “credo ut intelligam”—“I believe so that I might understand.” We find these words in the first chapter of Anselm’s Proslogion, which was originally titled Fides Quarens Intellectum, “Faith Seeking Understanding.” Here, St. Anselm famously states, “I do not seek to understand in order that I may believe, but rather, I believe so that I may understand.”1 This celebrated line of Anselm was based on the saying of St. Augustine, “crede, ut intelligas” (“believe so that you may understand”), which is found in his Tractates on the Gospel of John.2 The primary influence on the mind of Anselm was St. -

TWO ARGUMENTS of ST. ANSELM 1. in Proslogium II, St. Anselm

APPENDIX TWO ARGUMENTS OF ST. ANSELM 1. In Proslogium II, St. Anselm argues as follows: And assuredly that than which no greater being can be conceived, cannot exist in the understanding alone. For suppose it exists in the understanding alone: then it can be conceived to exist in reality; which is greater. Therefore, if that than which nothing greater can be conceived exists in the understanding alone, the very being than which nothing greater can be conceived, is one, than which a greater can be conceived. But obviously this is impossible. Hence, there is no doubt that there exists a being, than which nothing greater can be conceived, and it exists both in the understanding and in reality. 1 I shall take "exists in the understanding alone" to mean "is logically possible but not actual", and I shall take "a being than which no greater can be conceived" to mean "a being than which no greater being is logically possible", i.e., "a maximally great being". Moreover, I shall take "[If X] exists in the understanding alone, [then] it can be conceived to exist in reality, which is greater" to mean "If X is merely logically possible, then it would be greater if it were actual"; and I shall take it that the bearer of the predicate "would be greater if it were actual" is, at least, a logically possible object. Given these interpretations, Anselm's argument can be restated as follows: (1) If there were a logically possible object which is a maximally great being and it were merely logically possible (rather than both logically possible and actual), then it would be greater if it were actual. -

Kant on the Theoretical Arguments for God's Existence

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 1981 Kant on the Theoretical Arguments for God's Existence Ralph Herbert Slater University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Slater, Ralph Herbert, "Kant on the Theoretical Arguments for God's Existence" (1981). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 1543. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1543 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - KANT ON THE THEORETICAL ARGUMENTSFOR GOD'S EXISTENCE BY RALPH HERBERTSLATER A THESIS SUBMITTEDIN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTSFOR THE DEGREEOF MASTEROF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF RHODEISLAND 1981 KANT ON THE THEORETICAL ARGUMENTSFOR GOD'S EXISTENCE ABSTRACT Kant's statement limiting the material of cognitive categories to the empirical--that which appears to us in the manifold of sensible intuition--is examined in its relation to the concept of a Thing presumed by definition to be nonempirical or transcendent of the empirical, the God of modern theism. Kant's limiting statement forbids the appli cation of the a priori concepts of understanding, the categories of Existence, Causality, and determinate Necessity, in three proofs of the existence of a transcendent ens realissimum. Rather the application of these categories is limited to natural states of affairs in the sections of Kant's Dialectic devoted to three traditional arguments for God's existence. In what follows the Kantian theory of existence is explored in close detail as is Kant's limitation of the meaning of causality and necessity. -

The Ontological Proof: Kant’S Objections, Plantinga’S Reply

KSO 2012: 122 The Ontological Proof: Kant’s Objections, Plantinga’s Reply Gregory Robson, Duke University I. Introduction hroughout Immanuel Kant’s era, philosophers richly debated René Descartes’s seventeenth-century reform- ulation of the ontological argument that Anselm origin- T 1 nally advanced in the eleventh century. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant’s seminal analysis of the capacity and limits of reason and the implications of each for the claims of meta- physics, Kant offers a direct response to Descartes’s ontological proof, considering it against the backdrop of his own, broader line of argument in CPR. The result is perhaps the most des- tructive critique of the ontological argument ever produced.2 The aims of this essay are, first, to present Kant’s criticism of the ontological argument (or better, arguments3—herein I use 1 I am grateful to Gary Banham, Andrew Janiak, and two anonymous reviewers at Kant Studies Online for their feedback on earlier versions of this paper. 2 Alvin Plantinga has called Kant’s argument according to which existence is not a real property of things “[t]he most famous and important objection to the onto- logical argument” (Plantinga, God, Freedom, and Evil, 92). And, according to Kevin Harrelson, Kant’s rejection of the ontological argument on epistemic grounds constitutes “the most thorough criticism of that argument in the modern period” (Harrelson, The Ontological Argument from Descartes to Hegel, 167). 3 Of course, there is not just one ontological argument—some authors have even themselves offered several ontological arguments. Anselm himself, argues Nor- man Malcolm, put forward two distinct ontological arguments. -

The Modal Unity of Anselm's Proslogion

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-1996 The Modal Unity of Anselm's Proslogion Gary Mar Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Mar, Gary (1996) "The Modal Unity of Anselm's Proslogion," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil199613118 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol13/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. THE MODAL UNITY OF ANSELM'S PROSLOGION1 Gary Mar Anselm claimed that his Proslogion was a "single argument" sufficient to prove "that God truly exists," that God is "the supreme good requiring nothing else," as well as to prove "whatever we believe regarding the divine Being." In this paper we show how Anselm's argument in the Proslogion and in his Reply to Gaunilo can be reconstructed as a single argument. A logically elegant result is that the various stages of Anselm's argument are validated by standard axioms from contemporary modal logic. Anselm's prayerful meditation on the meaning of faith in the Proslogion was an attempt to find "one single argument ... that by itself would suffice to prove that God really exists, that He is the supreme good needing no other and is He whom all things have need of for their being and well-being, and also to prove whatever we believe about the Divine Being."2 Most contem porary philosophers, however, have narrowly focused on Proslogion II, and have consequently ignored Anselm's emphasis on a single argument in his work.3 In this paper I attempt to provide a logical map of Anselm's argu ment as a whole. -

Baylor University

ABSTRACT We Believe in the Communion of Saints: A Proposed Protestant Reclamation of the Doctrine Jonathan Scott Speegle Mentor: Bob Patterson, Ph.D. The corrective theology of the Reformation broke the historic union, at least in Europe, among all members of the kingdom of God. Perhaps the most serious Protestant loss—one still not satisfactorily recovered—is the doctrine of the communion between pilgrims and saints, especially when we remember that the Reformation declared all Christians to be saints, not just those who had been officially beatified and canonized. So, while the theology of the Church’s true treasury may have been corrected, Protestant Christians remain bereft of a satisfactory explication of their creedal claim that “we believe in the Communion of Saints” Hence there is a Protestant need for a recovered doctrine of the Communion of Saints as including the dead no less than the living. This proposed reclamation of the doctrine of the Communion of Saints living and dead for Protestant Christianity will be attempted in this dissertation in three parts. Part one will survey the historical development of the doctrine and outline the reasons for its ultimate rejection. Part two will construct a biblically grounded eschatological context through which we can understand, in part, the life beyond. Part three will explore the Church’s understanding of the various interactions between believers on earth and those in heaven. The story of Augustine’s mother Monica’s internment will introduce the Communion of Saints as a spiritual bond which knits together the faithful in this world and the saints beyond in a mystical organic and historic unity within which there exists a mutuality of faith, prayer, and love that is best and most fully expressed in the Eucharistic feast. -

Perspectives on Reincarnation Hindu, Christian, and Scientific

Perspectives on Reincarnation Hindu, Christian, and Scientific Edited by Jeffery D. Long Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Perspectives on Reincarnation Perspectives on Reincarnation Hindu, Christian, and Scientific Special Issue Editor Jeffery D. Long MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Jeffery D. Long Elizabethtown College USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2017 to 2018 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/reincarnation) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-535-9 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-536-6 (PDF) c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Jeffery D. Long Perspectives on Reincarnation: Hindu, Christian, and Scientific—Editor’s Introduction Reprinted from: Religions 2018, 9, 231, doi:10.3390/rel9080231 ...................