The Philosophy of Religion Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

Theology, History, and Religious Identification: Hegelian Methods in the Study of Religion

Theology, History, and Religious Identification: Hegelian Methods in the Study of Religion Kevin J. Harrelson Sophia International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Metaphysical Theology and Ethics ISSN 0038-1527 SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-012-0334-0 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-012-0334-0 Theology, History, and Religious Identification: Hegelian Methods in the Study of Religion Kevin J. Harrelson # Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 Abstract This essay deals with the impact of Hegel's philosophy of religion by examining his positions on religious identity and on the relationship between theol- ogy and history. I argue that his criterion for religious identity was socio-historical, and that his philosophical theology was historical rather than normative. These positions help explain some historical peculiarities regarding the effect of his philos- ophy of religion. Of particular concern is that although Hegel’s own aims were apologetic, his major influence on religious thought was in the development of various historical and critical approaches to religion. -

To Serve God... Religious Recognitions Created by the Faith Communities for Their Members Who Are Girl Scouts

TO SERVE GOD... RELIGIOUS RECOGNITIONS CREATED BY THE FAITH COMMUNITIES FOR THEIR MEMBERS WHO ARE GIRL SCOUTS African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Anglican Church in North America Baha’i God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life St. George Cross Unity of Mankind Unity of Mankind Unity of Mankind Service to Humanity Baptist Buddhist Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life Good Shepherd Padma Padma God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service Christian Methodist Episcopal (C.M.E.) Christian Science Churches of Christ God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service God and Country God and Country Loving Servant Joyful Servant Good Servant Giving Servant Faithful Servant Church of the Nazarene Community of Christ Eastern Orthodox God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life God and Service Light of Path of Exploring Community World Community St. George Chi-Rho Alpha Omega Prophet Elias the World the Disciple Together International Youth Service Episcopal Hindu Islamic God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life St. George Dharma Karma Bismillah In the Name of Allah Quratula’in Muslimeen Jewish Lutheran (Mormon) Church of Jesus Polish National Catholic Church Lehavah Bat Or Menorah Or Emunah Ora God and Me God and Family God and Church God and Life Lamb Christ of Latter-day Saints Love of God God and Community Bishop Thaddeus F. -

Introduction Sally Shuttleworth and Geoffrey Cantor

1 Introduction Sally Shuttleworth and Geoffrey Cantor “Reviews are a substitute for all other kinds of reading—a new and royal road to knowledge,” trumpeted Josiah Conder in 1811.1 Conder, who sub- sequently became proprietor and editor of the Eclectic Review, recognized that periodicals were proliferating, rapidly increasing in popularity, and becoming a major sector in the market for print. Although this process had barely begun at the time Conder was writing, the number of peri- odical publications accelerated considerably over the ensuing decades. According to John North, who is currently cataloguing the wonderfully rich variety of British newspapers and periodicals, some 125,000 titles were published in the nineteenth century.2 Many were short-lived, but others, including the Edinburgh Review (1802–1929) and Punch (1841 on), possess long and honorable histories. Not only did titles proliferate, but, as publishers, editors, and proprietors realized, the often-buoyant market for periodicals could be highly profitable and open to entrepreneurial exploitation. A new title might tap—or create—a previously unexploited niche in the market. Although the expensive quarterly reviews, such as the Edinburgh Review and the Quarterly, have attracted much scholarly attention, their circulation figures were small (they generally sold only a few thousand copies), and their readership was predominantly upper middle class. By contrast, the tupenny weekly Mirror of Literature is claimed to have achieved an unprecedented circulation of 150,000 when it was launched in 1822. A few later titles that were likewise cheap and aimed at a mass readership also achieved circulation figures of this magnitude. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

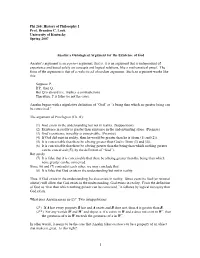

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

Schleiermacher and Otto

Jacqueline Mariña 1 Friedrich Schleiermacher and Rudolf Otto Two names often grouped together in the study of religion are Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1884) and Rudolf Otto (1869-1937). Central to their understanding of religion is the idea that religious experience, characterized in terms of feeling, lies at the heart of all genuine religion. In his book On Religion Schleiermacher speaks of religion as a “sense and taste for the Infinite.”1 It is “the immediate consciousness of the universal existence of all finite things, in and through the infinite” and is “to know and to have life in immediate feeling” (OR, p. 36). In The Christian Faith Schleiermacher grounds religion in the immediate self-consciousness and the “feeling of absolute dependence.”2 Influenced by Schleiermacher, Otto too grounds religion in an original experience of what he calls “the numinous,” which “completely eludes apprehension in terms of concepts” and is as such “ineffable;” it can only be grasped through states of feeling. (The Idea of the Holy, p. 5). In this paper I will critically examine their views on religion as feeling. The first part of the paper will be devoted to understanding how both men conceived of feeling and the reasons why they believed that religion had to be understood in its terms. In the second and third parts of the paper I will develop the views of each thinker individually, contrast them with one another, and discuss the peculiar problems that arise in relation to the thought of each. Common Elements in Schleiermacher and Otto Both Schleiermacher and Otto insist that religion cannot be reduced to ethics, aesthetics or metaphysics. -

Why Is the Philosophy of Religion Important?

1 Why is the Philosophy of Religion Important? Religion — whether we are theists, deists, atheists, gnostics, agnostics, Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Taoists, Confucians, Shintoists, Zoroastrians, animists, polytheists, pagans, Wiccans, secular humanists, Marxists, or cult devotees — is a matter of ultimate concern. Everything we are and do finally de- pends upon such questions as whether there is a God, whether we continue to exist after death, whether any God is active in human history, and whether human ethical relations have spiritual or supernatural dimensions. If God is real, then this is a different world than it would be if God were not real. The basic human need that probably exists for some sort of salvation, deliverance, release, liberation, pacification, or whatever it may be called, seems to be among the main foundations of all reli- gion. There may also be a basic human need for mystery, wonder, fear of the sacred, romantic worship of the inexplicable, awe in the presence of the completely different, or emotional response to the “numinous,” which is the topic of The Idea of the Holy by German theologian Rudolf Otto (1869-1937) and The Sacred and the Pro- fane by Romanian philosopher and anthropologist of religion Mir- cea Eliade (1907-1986). This need also may be a foundation of reli- gion. Yet doubt exists that humans feel any general need for mys- tery. On the contrary, the human need to solve mysteries seems to be more basic than any need to have mysteries. For example, mytho- logy in all known cultures has arisen from either the need or the de- sire to provide explanations for certain types of occurrences, either natural or interpersonal, and thus to attempt to do away with those mysteries. -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms?

Quaker Religious Thought Volume 118 Article 2 1-1-2012 Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms? Paul Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Paul (2012) "Is "Nontheist Quakerism" a Contradiction of Terms?," Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 118 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol118/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Religious Thought by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS “NONTHEIST QUAKERISM” A CONTRADICTION OF TERMS? Paul anderson s the term “Nontheist Friends” a contradiction of terms? On one Ihand, Friends have been free-thinking and open theologically, so liberal Friends have tended to welcome almost any nonconventional trend among their members. As a result, atheists and nontheists have felt a welcome among them, and some Friends in Britain and Friends General Conference have recently explored alternatives to theism. On the other hand, what does it mean to be a “Quaker”—even among liberal Friends? Can an atheist claim with integrity to be a “birthright Friend” if one has abandoned faith in the God, when the historic heart and soul of the Quaker movement has diminished all else in service to a dynamic relationship with the Living God? And, can a true nontheist claim to be a “convinced Friend” if one declares being unconvinced of God’s truth? On the surface it appears that one cannot have it both ways. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

The Philosophy of Religion Past and Present: Philosophical Theology Or the Critical Cross

“The Philosophy of Religion Past and Present: Philosophical Theology or the Critical Cross- Examination of Institutionalized Ritual and Belief?”1 Bryan Rennie Vira I. Heinz Professor of Religion Westminster College October, 2014 Abstract The disciplinary or “traditional” philosophy of religion has come under increasing attacks that claim that it is unacceptably focused on specifically monotheist, and even specifically Christian, issues to such an extent that it does not merit the appellation “philosophy of religion.” It should, it has been claimed, more honestly and accurately be termed “philosophical theology.” A discipline more reasonably entitled “philosophy of religion” or perhaps “philosophy of religions” should expand its focus to include the traditionally philosophical questions of ontology, epistemology, and ethics raised not only by the history of the Christian, or even the other Abrahamic, traditions but by all such institutionalized systems of ritual and belief. Contemporary movements in both Philosophy and the Study of Religion have begun to raise this point with increasing emphasis. What might such a reformed philosophy of religion(s) look like, and what role might it play in the future of the academy? What Do I Mean by “Philosophy”? At the outset it behooves me to make some attempt to clarify what I mean by (Western) philosophy. The word, of course, has a plurality of senses, and one is never justified in claiming that any given singular sense is the “right” one. Philosophy does mean a personal, possibly very 1 The following paper draws heavily on previously published work, especially Rennie 2006, 2010, and 2012. Rennie Philosophy of Religions: Past and Present 2 loose, system of beliefs relative to some identifiable class, as in “my philosophy of life.” It can also mean speculative metaphysics, as in “The subject of the attributes of deity was until recent times reserved for the speculations of theology and philosophy” (Pettazzoni 1956: 1).