Maimonides and Aquinas on Divine Attributes the Importance of Avicenna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phil102: Intro to Philosophy: Knowledge & Reality

PHIL102: INTRO TO PHILOSOPHY: KNOWLEDGE & REALITY section 3, schedule #22716 MW 4:00-5:15 pm in EBA 343 Dr. Robert Francescotti Office Hours (Arts & Letters, 438): Monday 5:45–7 pm, Wednesday 12:30–1:30 pm, & Thursday 2–4 pm Office phone & e-mail: 619-594-6585, [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This course satisfies the Philosophy & Religious Studies section of the Humanities requirement of the Foundations of Learning component of the General Education requirements. - description in SDSU’s General Catalog: Introduction to philosophical inquiry with emphasis on problems of knowledge and reality. Students are encouraged to think independently and formulate their own tentative conclusions. - a fuller description of my section: You will learn about the philosophical method by exploring some main areas of philosophical interest. The first issue we will discuss is whether God exists. We will consider a few arguments designed to show that God exists along with an argument that aims to show that God does not exist. This first section of the course is a good introduction to the structure of argumentation (an essential tool of the philosophical method). Then we will investigate the Free Will debate. Science has shown that much of our behavior is the result of factors beyond our control. The environment in which we were raised obviously greatly affects our behavior. Non-conscious mental activity and genetic factors are also thought to play a major role. Of course, the state of one’s brain is a major culprit as well. However, if our actions are the result of these factors, which seem largely out of our control, then in what sense can we be considered “free”? And if we do not act in a truly free manner, then can we be held responsible for our actions? Many people believe that in addition to the body, there is some immaterial aspect to our being. -

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

Absolute Identity and the Trinity

Absolute Identity and the Trinity Chris Tweedt Trinititarians are charged with (at least) two contradictions. First, the Father is God and the Son is God, so it seems to follow that the Father is the Son. Trinitarians affirm the premises but deny the conclusion, which seems contradictory. Second, the Father is a god, the Son is a god, and the Holy Spirit is a god, but the Father isn't the Son, the Father isn't the Holy Spirit, and the Son isn't the Holy Spirit. This seems to entail that there are three gods. Again, Trinitarians affirm the premises but deny the conclusion. There are two main views of the Trinity that are designed to (among other things) avoid these alleged contradictions. These views, however, have problems. In this paper, I present a resolution to these alleged contradictions that a Trinitarian proponent of divine simplicity can endorse without succumbing to the problems of the two main current views. What is surprising about the view I'll propose is that it is helped by divine simplicity. This is surprising because many current Trinitarian views either reject divine simplicity or find it a difficult doctrine to maintain. In section 1, I'll better describe the alleged contradictions the Trinitarian needs to dispel and the way in which the Trinitarian needs to dispel these alleged contradic- tions. In section 2, I'll give the two main ways to dispel these alleged contradictions and give the problems with these views. In sections 3{5, I'll propose and defend a view that dispels the alleged contradictions. -

Theories of Truth. Bibliography on Primary Medieval Authors

Theories of Truth. Bibliography on Primary Medieval Authors https://www.ontology.co/biblio/truth-medieval-authors.htm Theory and History of Ontology by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] History of Truth. Selected Bibliography on Medieval Primary Authors The Authors to which I will devote an entire page are marked with an asterisk (*). Hilary of Poitiers Augustine of Hippo (*) Boethius (*) Isidore of Seville John Scottus Eriugena (*) Isaac Israeli Avicenna (*) Anselm of Canterbury (*) Peter Abelard (*) Philip the Chancellor Robert Grosseteste William of Auvergne Albert the Great Bonaventure Thomas Aquinas (*) Henry of Ghent Siger of Brabant John Duns Scotus (*) Hervaeus Natalis Giles of Rome Durandus of St. Pourçain Peter Auriol Walter Burley William of Ockham (*) Robert Holkot John Buridan (*) 1 di 14 22/09/2016 09:25 Theories of Truth. Bibliography on Primary Medieval Authors https://www.ontology.co/biblio/truth-medieval-authors.htm Gregory of Rimini William of Heytesbury Peter of Mantua Paul of Venice Hilary of Poitiers (ca. 300 - 368) Texts 1. Meijering, E.P. 1982. Hilary of Poitiers on the Trinity. De Trinitate 1, 1-19, 2, 3. Leiden: Brill. In close cooperation with J. C. M: van Winden. On truth see I, 1-14. Studies Augustine of Hippo ( 354 - 430) Texts Studies 1. Boyer, Charles. 1921. L'idée De Vérité Dans La Philosophie De Saint Augustin. Paris: Gabriel Beauchesne. 2. Kuntz, Paul G. 1982. "St. Augustine's Quest for Truth: The Adequacy of a Christian Philosophy." Augustinian Studies no. 13:1-21. 3. Vilalobos, José. 1982. Ser Y Verdad En Agustín De Hipona. Sevilla: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla. -

Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Hyde Dawn Krista University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses Graduate Works 4-16-2012 Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Hyde Dawn Krista University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Krista, Hyde Dawn, "Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife" (2012). Theses. 261. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Aquinas: Soul-Body Connection and the Afterlife Krista Hyde M.L.A., Washington University in St. Louis, 2010 B.A., Philosophy, Southeast Missouri State University – Cape Girardeau, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri – St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Philosophy April 2012 Advisory Committee Gualtiero Piccinini, Ph.D. Chair Jon McGinnis, Ph.D. John Brunero, Ph.D. Copyright, Krista Hyde, 2012 Abstract Thomas Aquinas nearly succeeds in addressing the persistent problem of the mind-body relationship by redefining the human being as a body-soul (matter-form) composite. This redefinition makes the interaction problem of substance dualism inapplicable, because there is no soul “in” a body. However, he works around the mind- body problem only by sacrificing an immaterial afterlife, as well as the identity and separability of the soul after death. Additionally, Thomistic psychology has difficulty accounting for the transmission of universals, nor does it seem able to overcome the arguments for causal closure. -

An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 37 Issue 3 Article 3 7-1-2020 An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity Katherin A. Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Rogers, Katherin A. (2020) "An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 37 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. DOI: 10.37977/faithphil.2020.37.3.3 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol37/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. applyparastyle "fig//caption/p[1]" parastyle "FigCapt" applyparastyle "fig" parastyle "Figure" AQ1–AQ5 AN ANSELMIAN APPROACH TO DIVINE SIMPLICITY Katherin A. Rogers The doctrine of divine simplicity (DDS) is an important aspect of the clas- sical theism of philosophers like Augustine, Anselm, and Thomas Aquinas. Recently the doctrine has been defended in a Thomist mode using the intrin- sic/extrinsic distinction. I argue that this approach entails problems which can be avoided by taking Anselm’s more Neoplatonic line. This does involve AQ6 accepting some controversial claims: for example, that time is isotemporal and that God inevitably does the best. The most difficult problem involves trying to reconcile created libertarian free will with the Anselmian DDS. But for those attracted to DDS the Anselmian approach is worth considering. -

St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2020 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death Christopher Choma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Christianity Commons, Epistemology Commons, European History Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, History of Religion Commons, Metaphysics Commons, Philosophy of Mind Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Choma, Christopher, "St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death" (2020). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1048. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1048 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death By: Christopher Choma Sponsored by: Dr. Joseph Li Vecchi Readers: Dr. Howard Ducharme Dr. Nathan Blackerby 2 Table of Contents Introduction p. 4 Section One: Three General Views of Human Nature p. -

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen's Implicit Rejection of Kant's Critique of Judaism

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen’s Implicit Rejection of Kant’s Critique of Judaism George Y. Kohler* “Moses did not make religion a part of virtue, but he saw and ordained the virtues to be part of religion…” Josephus, Against Apion 2.17 Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) was arguably the only Jewish philosopher of modernity whose standing within the general philosophical developments of the West equals his enormous impact on Jewish thought. Cohen founded the influential Marburg school of Neo-Kantianism, the leading trend in German Kathederphilosophie in the second half of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century. Marburg Neo-Kantianism cultivated an overtly ethical, that is, anti-Marxist, and anti-materialist socialism that for Cohen increasingly concurred with his philosophical reading of messianic Judaism. Cohen’s Jewish philosophical theology, elaborated during the last decades of his life, culminated in his famous Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism, published posthumously in 1919.1 Here, Cohen translated his neo-Kantian philosophical position back into classical Jewish terms that he had extracted from Judaism with the help of the progressive line of thought running from * Bar-Ilan University, Department of Jewish Thought. 1 Hermann Cohen, Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums, first edition, Leipzig: Fock, 1919. I refer to the second edition, Frankfurt: Kaufmann, 1929. English translation by Simon Kaplan, Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism (New York: Ungar, 1972). Henceforth this book will be referred to as RR, with reference to the English translation by Kaplan given after the German in square brackets. -

Comparativeurban Studies Project

COMPARATIVE URBAN STUDIES PROJECT URBAN UPDATE September 2007 NO. 12 Cities and Fundamentalisms WRITTEN BY: Nezar AlSayyad, Professor of Architecture, Planning, and Urban History & Chair of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California at Berkeley; Mejgan Massoumi, Program Assistant, Comparative Urban Studies Project (2005-2007); Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Assistant Professor, Draper Faculty Fellow (The City), New York University. With the unanticipated resur- gence of religious and ethnic loy- alties across the world, commu- nities are returning to, reinvigo- rating, and giving new meaning to religions and their common practices. Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism, among others, are experiencing new in- fl uxes of commitments and tra- ditions. These changes have been coupled with the breakdown of order and of state power under the neo-liberal economic para- Top Row, Left to Right: Salwa Ismail, Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Raka Ray, Blair Ruble, Renu Desai, Nezar AlSayyad. Bottom Row, Left to Right: digm of civil society which have Omri Elisha, Emily Gottreich, Mona Harb, Mejgan Massoumi. created vacuums in the provi- sion of social services. Religious groups in many countries around the world are increasingly providing those services left unattended to by state bureaucracies. The once sacred divide between church and COMPARATIVE URBAN STUDIES PROJECT state or the confi nement of religion to the pri- fundamentalisms in several parts of the world. The vate sphere is now being vigorously challenged systematic transformation of the urban landscape as radical religious groups not only gain ground through various strategies of religious funda- within sovereign nation-states but in fact forge mentalism has led to the redefi nition of minority enduring and powerful transnational connections space in many cities. -

Conceptual Analysis and the Essence of Space: Kant's Metaphysical

AGPh 2015; 97(4): 416–457 James Messina* Conceptual Analysis and the Essence of Space: Kant’s Metaphysical Exposition Revisited DOI 10.1515/agph-2015-0017 Abstract: I offer here an account of the methodology, historical context, and content of Kant’s so-called “Metaphysical Exposition of the Concept of Space” (MECS). Drawing on Critical and pre-Critical texts, I first argue that the arguments making up the MECS rest on a kind of conceptual analysis, one that yields (analytic) knowledge of the essence of space. Next, I situate Kant’s MECS in what I take to be its proper historical context: the debate between the Wolffians and Crusius about the correct analysis of the concept of space. Finally, I draw on the results of previous sections to provide a reconstruction of Kant’s so-called “first apriority argument.” On my reconstruction, the key premise of the argument is a claim to the effect that space grounds the possibility of the co-existence of whatever things occupy it. “To investigate the essences of things is the busi- ness and the end of philosophy.” (AA 24:115) 1 Introduction In the Transcendental Aesthetic of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant argues that space is the a priori form of outer intuition (call this the Form Thesis).¹,² Kant’s 1 References to the Critique of Pure Reason are given according to the pagination of the first (A) and second (B) editions. In quotations I have followed Critique of Pure Reason (Kant 1998). References to other works by Kant are given by volume and page number of the Berlin Akademie edition (cited as AA). -

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

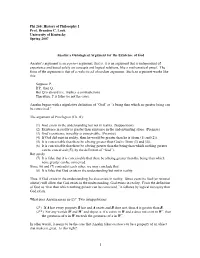

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

The Political Regard in Medieval Islamic Thought Yavari, Neguin

www.ssoar.info The Political Regard in Medieval Islamic Thought Yavari, Neguin Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Yavari, N. (2019). The Political Regard in Medieval Islamic Thought. Historical Social Research, 44(3), 52-73. https:// doi.org/hsr.44.2019.3.52-73 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de The Political Regard in Medieval Islamic Thought ∗ Neguin Yavari Abstract: »Der politische Aspekt im Islamischen Denken des Mittelalters«. Glob- al intellectual history has attracted traction in the past decade, but the field remains focused on the modern period and the diffusion of Western political concepts, ideologies, and methodologies. This paper suggests that juxtaposing political texts from the medieval Islamic world with their Christian counterparts will allow for a better understanding of the contours of the debate on the space for politics, framed in primary sources as the perennial tug of war be- tween religious and lay authority. The implications of this line of inquiry for the history of European political thought are significant as well. Many of the prem- ises and characteristics that are considered singularly European, such as conti- nuity between past and present, as well as a strong performative regard to po- litical thought, are equally present in non-European (in this instance Islamic) debates.