The Philosophical Proof for God's Existence Between Europe and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

On the Logic of the Ontological Argument∗ X

Paul E. Oppenheimer and Edward N. Zalta 2 by `9y(y =x)' and the claim that x has the property of existence by `E!x'. That is, we represent the difference between the two claims by exploiting the distinction between quantifying over x and predicating existence of On the Logic of the Ontological Argument∗ x. We shall sometimes refer to this as the distinction between the being of x and the existence of x. Thus, instead of reading Anselm as having discovered a way of inferring God's actuality from His mere possibility, Paul E. Oppenheimer we read him as having discovered a way of inferring God's existence from Thinking Machines Corporation His mere being. Another important feature of our reading concerns the fact that we and take the phrase \that than which none greater can be conceived" seriously. Certain inferences in the ontological argument are intimately linked to the logical behavior of this phrase, which is best represented as a definite Edward N. Zalta description.3 If we are to do justice to Anselm's argument, we must not Philosophy Department syntactically eliminate descriptions the way Russell does. One of the Stanford University highlights of our interpretation is that a very simple inference involving descriptions stands at the heart of the argument.4 Saint Anselm of Canterbury offered several arguments for the existence The Language and Logic Required for the Argument of God. We examine the famous ontological argument in Proslogium ii. Many recent authors have interpreted this argument as a modal one.1 But We shall cast our new reading in a standard first-order language. -

THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952)

Georg Hegel (1770-1831) ................................ 30 Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) ................. 32 Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (1804-1872) ...... 32 John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) .......................... 33 Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) ..................... 33 Karl Marx (1818-1883).................................... 34 Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) ................ 35 Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914).............. 35 William James (1842-1910) ............................ 36 The Modern World 1900-1950 ............................. 36 Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) .................... 37 Ahad Ha'am (1856-1927) ............................... 38 Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) ............. 38 Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) ....................... 39 Henri Bergson (1859-1941) ............................ 39 Contents John Dewey (1859–1952) ............................... 39 Introduction....................................................... 1 THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952) ..................... 40 The Ancient World 700 BCE-250 CE..................... 3 Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) ................... 40 Introduction Thales of Miletus (c.624-546 BCE)................... 3 William Du Bois (1868-1963) .......................... 41 Laozi (c.6th century BCE) ................................. 4 Philosophy is not just the preserve of brilliant Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) ........................ 41 Pythagoras (c.570-495 BCE) ............................ 4 but eccentric thinkers that it is popularly Max Scheler -

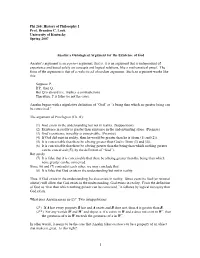

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

Divine Utilitarianism

Liberty University DIVINE UTILITARIANISM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Masters of Arts in Philosophical Studies By Jimmy R. Lewis January 16, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One: Introduction ……………………………...……………..……....3 Statement of the Problem…………………………….………………………….3 Statement of the Purpose…………………………….………………………….5 Statement of the Importance of the Problem…………………….……………...6 Statement of Position on the Problem………………………...…………….......7 Limitations…………………………………………….………………………...8 Development of Thesis……………………………………………….…………9 Chapter Two: What is meant by “Divine Utilitarianism”..................................11 Introduction……………………………….…………………………………….11 A Definition of God.……………………………………………………………13 Anselm’s God …………………………………………………………..14 Thomas’ God …………………………………………………………...19 A Definition of Utility .…………………………………………………………22 Augustine and the Good .……………………………………………......23 Bentham and Mill on Utility ……………………………………………25 Divine Utilitarianism in the Past .……………………………………………….28 New Divine Utilitarianism .……………………………………………………..35 Chapter Three: The Ethics of God ……………………………………………45 Divine Command Theory: A Juxtaposition .……………………………………45 What Divine Command Theory Explains ………………….…………...47 What Divine Command Theory Fails to Explain ………………………47 What Divine Utilitarianism Explains …………………………………………...50 Assessing the Juxtaposition .…………………………………………………....58 Chapter Four: Summary and Conclusion……………………………………...60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..64 2 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Statement of the -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

Gce a Level Marking Scheme

GCE A LEVEL MARKING SCHEME SUMMER 2018 A LEVEL RELIGIOUS STUDIES - COMPONENT 2 PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION A120U20-1 © WJEC CBAC Ltd. INTRODUCTION This marking scheme was used by WJEC for the 2018 examination. It was finalised after detailed discussion at examiners' conferences by all the examiners involved in the assessment. The conference was held shortly after the paper was taken so that reference could be made to the full range of candidates' responses, with photocopied scripts forming the basis of discussion. The aim of the conference was to ensure that the marking scheme was interpreted and applied in the same way by all examiners. It is hoped that this information will be of assistance to centres but it is recognised at the same time that, without the benefit of participation in the examiners' conference, teachers may have different views on certain matters of detail or interpretation. WJEC regrets that it cannot enter into any discussion or correspondence about this marking scheme. © WJEC CBAC Ltd. Marking guidance for examiners, please apply carefully and consistently: Positive marking It should be remembered that candidates are writing under examination conditions and credit should be given for what the candidate writes, rather than adopting the approach of penalising him/her for any omissions. It should be possible for a very good response to achieve full marks and a very poor one to achieve zero marks. Marks should not be deducted for a less than perfect answer if it satisfies the criteria of the mark scheme. Exemplars in the mark scheme are only meant as helpful guides. -

Leibniz and Theodicy Nicholas R. Green

Leibniz and the Theodicy Modern Western Philosophy February 23rd, 2010 Is this the best of all possible worlds? • Leibniz asserts that it is • His argument depends on two essential components – Principle of Sufficient Reason – A cosmological argument for God’s existence A Brief Review of the PSR “…we consider that we can find no true or existent fact, no true assertion, without there being sufficient reason why it is thus and not otherwise, although most of the time these reasons cannot be known to us.” (Monadology 32, AW 278A) The take away? There is no effect without a cause. To understand the Theodicy, we need God. Let’s prove Him. A Cosmological Proof for God’s Existence CPG 1: A given event or object requires sufficient reason for its occurrence (I.e., every effect must have a cause) CPG 2: The cause of that given event (its sufficient reason) must itself have a cause (sufficient reason) CPG 3: There must be a stop to the infinite regress of causes CPG 4: The termination of the series of sufficient reasons must necessarily exist, and exist outside the chain CPG 5: This is God In Leibniz’s Words… “There must be a sufficient reason in contingent truths, or truths of fact, that is, in the series of things distributed throughout the universe of creatures, where the resolution into particular reasons could proceed into unlimited detail…And since all of this detail involves nothing but other prior and or more detailed contingents, each of which needs a similar analysis in order to give its reason…It must be the case that the sufficient or ultimate reason is outside the the sequence or series of this multiplicity of contingencies, however infinite it may be…The ultimate reason of things must be in a necessary substance in which the diversity of changes is only eminent, as in its source. -

Reading Questions for Phil 251.200, Fall 2012 (Daniel)

Reading Questions for Phil 251.200, Fall 2012 (Daniel) Class One: What is Philosophy? (Aug. 28) How is philosophy different from mythology? How is philosophy different from religion? How is philosophy different from science? What does it mean to say that the “love of wisdom” is concerned with the justification of opinions? Why is giving reasons for your beliefs important regarding the main areas of philosophy (e.g., metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, and logic)? Class Two: The Activity of Philosophy and The Life of Reason [two readings] (Aug. 30) How is the appeal to reason different from an appeal to authority, emotion, and self- interest? What are the criteria for determining whether your reasons for doing or believing something are justified (i.e., “good” reasons)? According to Socrates, “the unexamined life is not worth living”: why?—especially since it is obvious that human beings are not essentially or inherently rational. How can reason be used to resolve conflicts in feelings and among different people? Why is appealing to reason preferable to relying on authority or allowing people to believe whatever they want about the world? Class Three: Knowledge and Skepticism (Sept. 4) What distinguishes propositional knowledge, “knowing how,” and “knowledge by acquaintance”? How does Clifford’s insistence on having evidence highlight the moral significance of distinguishing belief and knowledge? What are the three necessary conditions for knowledge? Give an example of a Gettier- case exception—that is, a case of -

The Philosophy of Religion Contents

The Philosophy of Religion Course notes by Richard Baron This document is available at www.rbphilo.com/coursenotes Contents Page Introduction to the philosophy of religion 2 Can we show that God exists? 3 Can we show that God does not exist? 6 If there is a God, why do bad things happen to good people? 8 Should we approach religious claims like other factual claims? 10 Is being religious a matter of believing certain factual claims? 13 Is religion a good basis for ethics? 14 1 Introduction to the philosophy of religion Why study the philosophy of religion? If you are religious: to deepen your understanding of your religion; to help you to apply your religion to real-life problems. Whether or not you are religious: to understand important strands in our cultural history; to understand one of the foundations of modern ethical debate; to see the origins of types of philosophical argument that get used elsewhere. The scope of the subject We shall focus on the philosophy of religions like Christianity, Islam and Judaism. Other religions can be quite different in nature, and can raise different questions. The questions in the contents list indicate the scope of the subject. Reading You do not need to do extra reading, but if you would like to do so, you could try either one of these two books: Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford University Press, third edition, 2003. Chad Meister, Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Routledge, 2009. 2 Can we show that God exists? What sorts of demonstration are there? Proofs in the strict sense: logical and mathematical proof Demonstrations based on external evidence Demonstrations based on inner experience How strong are these different sorts of demonstration? Which ones could other people reject, and on what grounds? What sort of thing could have its existence shown in each of these ways? What might we want to show? That God exists That it is reasonable to believe that God exists The ontological argument Greek onta, things that exist. -

Ontological Arguments

Ontological Arguments According to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would be an argument that established the existence of God using nothing more than the resources of logical reasoning. That is, according to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would be an argument that had nothing but truths of logic—i.e. truths that can be known a priori by any reasonable cognitive agent—for its premises, and reached the conclusion that God exists using nothing but logically impeccable inferences from those premises. Hence, according to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would show that there is a sense in which it is a logical theorem—a truth provable a priori by any reasonable cognitive agent—that God exists. Given this common philosophical understanding, we can say that the aim of those who put forward what they call “ontological arguments” is to show that, merely in virtue of being reasonable in the formation of beliefs that it holds on the basis of reason alone, any reasonable cognitive agent holds beliefs that jointly entail that God exists. Moreover, we can observe that a successful ontological argument will be such that none of its premises can be reasonably rejected by a reasonable cognitive agent; and it will be such that no reasonable being can reasonably deny that the conclusion of the argument is entailed by the premises of the argument; and it will have the conclusion that God exists. The last claim in the previous paragraph is not exactly right. Many so-called “ontological arguments” do not end with the words “Therefore God exists”. -

Evil and the Ontological Disproof

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Evil and the Ontological Disproof Carl J. Brownson III The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2155 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EVIL AND THE ONTOLOGICAL DISPROOF by CARL BROWNSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, City University of New York 2017 1 © 2017 CARL BROWNSON All Rights Reserved ii Evil and the Ontological Disproof by Carl Brownson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Graham Priest Chair of Examining Committee Date Iakovos Vasiliou Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Stephen Grover, advisor Graham Priest Peter Simpson Nickolas Pappas Robert Lovering THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Evil and the Ontological Disproof by Carl Brownson Advisor: Stephen Grover This dissertation is a revival of the ontological disproof, an ontological argument against the existence of God. The ontological disproof, in its original form, argues that God is impossible, because if God exists, he must exist necessarily, and necessary existence is impossible. The notion of necessary existence has been largely rehabilitated since this argument was first offered in 1948, and the argument has accordingly lost much of its force.