The Ontological Proof: Kant’S Objections, Plantinga’S Reply

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952)

Georg Hegel (1770-1831) ................................ 30 Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) ................. 32 Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (1804-1872) ...... 32 John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) .......................... 33 Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) ..................... 33 Karl Marx (1818-1883).................................... 34 Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) ................ 35 Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914).............. 35 William James (1842-1910) ............................ 36 The Modern World 1900-1950 ............................. 36 Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) .................... 37 Ahad Ha'am (1856-1927) ............................... 38 Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) ............. 38 Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) ....................... 39 Henri Bergson (1859-1941) ............................ 39 Contents John Dewey (1859–1952) ............................... 39 Introduction....................................................... 1 THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952) ..................... 40 The Ancient World 700 BCE-250 CE..................... 3 Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) ................... 40 Introduction Thales of Miletus (c.624-546 BCE)................... 3 William Du Bois (1868-1963) .......................... 41 Laozi (c.6th century BCE) ................................. 4 Philosophy is not just the preserve of brilliant Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) ........................ 41 Pythagoras (c.570-495 BCE) ............................ 4 but eccentric thinkers that it is popularly Max Scheler -

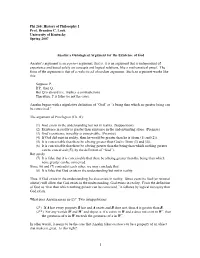

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

Curriculum Vitae of Alvin Plantinga

CURRICULUM VITAE OF ALVIN PLANTINGA A. Education Calvin College A.B. 1954 University of Michigan M.A. 1955 Yale University Ph.D. 1958 B. Academic Honors and Awards Fellowships Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, 1968-69 Guggenheim Fellow, June 1 - December 31, 1971, April 4 - August 31, 1972 Fellow, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1975 - Fellow, Calvin Center for Christian Scholarship, 1979-1980 Visiting Fellow, Balliol College, Oxford 1975-76 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowships, 1975-76, 1987, 1995-6 Fellowship, American Council of Learned Societies, 1980-81 Fellow, Frisian Academy, 1999 Gifford Lecturer, 1987, 2005 Honorary Degrees Glasgow University, l982 Calvin College (Distinguished Alumni Award), 1986 North Park College, 1994 Free University of Amsterdam, 1995 Brigham Young University, 1996 University of the West in Timisoara (Timisoara, Romania), 1998 Valparaiso University, 1999 2 Offices Vice-President, American Philosophical Association, Central Division, 1980-81 President, American Philosophical Association, Central Division, 1981-82 President, Society of Christian Philosophers, l983-86 Summer Institutes and Seminars Staff Member, Council for Philosophical Studies Summer Institute in Metaphysics, 1968 Staff member and director, Council for Philosophical Studies Summer Institute in Philosophy of Religion, 1973 Director, National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar, 1974, 1975, 1978 Staff member and co-director (with William P. Alston) NEH Summer Institute in Philosophy of Religion (Bellingham, Washington) 1986 Instructor, Pew Younger Scholars Seminar, 1995, 1999 Co-director summer seminar on nature in belief, Calvin College, July, 2004 Other E. Harris Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching (Danforth Foundation), 1968 Member, Council for Philosophical Studies, 1968-74 William Evans Visiting Fellow University of Otago (New Zealand) 1991 Mentor, Collegium, Fairfield University 1993 The James A. -

The Philosophy of Religion Contents

The Philosophy of Religion Course notes by Richard Baron This document is available at www.rbphilo.com/coursenotes Contents Page Introduction to the philosophy of religion 2 Can we show that God exists? 3 Can we show that God does not exist? 6 If there is a God, why do bad things happen to good people? 8 Should we approach religious claims like other factual claims? 10 Is being religious a matter of believing certain factual claims? 13 Is religion a good basis for ethics? 14 1 Introduction to the philosophy of religion Why study the philosophy of religion? If you are religious: to deepen your understanding of your religion; to help you to apply your religion to real-life problems. Whether or not you are religious: to understand important strands in our cultural history; to understand one of the foundations of modern ethical debate; to see the origins of types of philosophical argument that get used elsewhere. The scope of the subject We shall focus on the philosophy of religions like Christianity, Islam and Judaism. Other religions can be quite different in nature, and can raise different questions. The questions in the contents list indicate the scope of the subject. Reading You do not need to do extra reading, but if you would like to do so, you could try either one of these two books: Brian Davies, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford University Press, third edition, 2003. Chad Meister, Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Routledge, 2009. 2 Can we show that God exists? What sorts of demonstration are there? Proofs in the strict sense: logical and mathematical proof Demonstrations based on external evidence Demonstrations based on inner experience How strong are these different sorts of demonstration? Which ones could other people reject, and on what grounds? What sort of thing could have its existence shown in each of these ways? What might we want to show? That God exists That it is reasonable to believe that God exists The ontological argument Greek onta, things that exist. -

Ontological Arguments

Ontological Arguments According to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would be an argument that established the existence of God using nothing more than the resources of logical reasoning. That is, according to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would be an argument that had nothing but truths of logic—i.e. truths that can be known a priori by any reasonable cognitive agent—for its premises, and reached the conclusion that God exists using nothing but logically impeccable inferences from those premises. Hence, according to common philosophical understanding, a successful ontological argument would show that there is a sense in which it is a logical theorem—a truth provable a priori by any reasonable cognitive agent—that God exists. Given this common philosophical understanding, we can say that the aim of those who put forward what they call “ontological arguments” is to show that, merely in virtue of being reasonable in the formation of beliefs that it holds on the basis of reason alone, any reasonable cognitive agent holds beliefs that jointly entail that God exists. Moreover, we can observe that a successful ontological argument will be such that none of its premises can be reasonably rejected by a reasonable cognitive agent; and it will be such that no reasonable being can reasonably deny that the conclusion of the argument is entailed by the premises of the argument; and it will have the conclusion that God exists. The last claim in the previous paragraph is not exactly right. Many so-called “ontological arguments” do not end with the words “Therefore God exists”. -

The Primacy of Faith and the Priority of Reason: a Justification for Public Recognition of Revealed Truth

The Primacy of Faith and the Priority of Reason: A Justification for Public Recognition of Revealed Truth Fr. David Pignato St. John’s Seminary, Brighton, MA The Catholic tradition of the primacy of faith, as taught by both Augustine and Anselm, is not an endorsement of fideism, but rather a rule of respecting the supra-rational nature of divinely revealed truths that must be accepted by faith. The same tradition upholds the priority of unaided reason, which can confirm the truth of faith by examining the evidence of revelation, or the motives of credibility. This critical role of reason justifies the individual assent of faith and also offers a basis upon which a secular state, reliant on reason, could conceivably refer to revealed truths, to help it discover the objective moral principles that aid the state in its effort to promote human dignity and the common good. Credo ut intelligam “Credo ut intelligam.” Perhaps second only to “Cur Deus Homo,” no other words come to mind more quickly at the mention of St. Anselm than “credo ut intelligam”—“I believe so that I might understand.” We find these words in the first chapter of Anselm’s Proslogion, which was originally titled Fides Quarens Intellectum, “Faith Seeking Understanding.” Here, St. Anselm famously states, “I do not seek to understand in order that I may believe, but rather, I believe so that I may understand.”1 This celebrated line of Anselm was based on the saying of St. Augustine, “crede, ut intelligas” (“believe so that you may understand”), which is found in his Tractates on the Gospel of John.2 The primary influence on the mind of Anselm was St. -

A Critique of the Free Will Defense, a Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’S Solution to the Problem of Evil

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2013 A Critique of the Free Will Defense, A Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’s Solution To the Problem of Evil. Justin Ykema University of New Hampshire - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Medieval Studies Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ykema, Justin, "A Critique of the Free Will Defense, A Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’s Solution To the Problem of Evil." (2013). Honors Theses and Capstones. 119. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/119 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of New Hampshire Department of Philosophy 2012-2013 A Critique of the Free Will Defense A Comprehensive Look at Alvin Plantinga’s Solution To the Problem of Evil. by Justin Ykema Primary Reader: Jennifer Armstrong Additional Readers: Willem deVries, Paul McNamara & Ruth Sample Graties tibi ago, domine. Haec credam a deo pio, a deo justo, a deo scito? Cruciatus in crucem. Tuus in terra servus, nuntius fui; officium perfeci. Cruciatus in crucem. Eas in crucem. 1 Section I: Introduction Historically, the problem of evil exemplifies an apparent paradox. The paradox is, if God exists, and he is all-good, all-knowing, and all-powerful, how does evil exist in the world when God created everything the world contains? Many theologians have put forth answers to solve this problem, and one of the proposed solutions put forth is the celebrated Free Will Defense, which claims to definitively solve the problem of evil. -

Department of Philosophy

St. Jerome’s University in the University of Waterloo Department of Philosophy Syllabus Fall Term 2019 Course: PHIL 230J – GOD AND PHILOSOPHY: Section 001 Instructor: Professor Nikolaj Zunic Class Times: 10:00 am – 11:20 am on Mondays and Wednesdays Class Location: SJ1 3016 Office: SH 2003 [Sweeney Hall on the St. Jerome’s Campus] Phone: (519) 884-8111 ext. 28229 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays and Wednesdays: 9:30 am – 10:00 am and 2:30 pm – 3:30 pm; and by appointment: please e-mail the professor. Required Text Brian Davies, Philosophy of Religion: A Guide and Anthology, Oxford University Press, 2000. [ISBN 978-0-19-875194-6] Course Description Does God exist? Can God’s existence be proven? What is God’s essence? What is the human being’s relationship to God? What is faith? Is it possible to know God? Is God-talk meaningful and coherent? Does God have a rightful place in philosophical discourse? These are some of the many questions and problems that will be investigated in PHIL 230J: GOD AND PHILOSOPHY this term. As the title of the course suggests, we will be exploring the relationship between God “and” philosophy, generally speaking, not simply a philosophical concept of God. The emphasis should be placed on the conjunction which signifies a relation. To be sure, the reality of God is much greater than what is conceived within the parameters of philosophy alone. Blaise Pascal famously distinguished between the “God of the prophets” and the “God of the philosophers”. Bearing this in mind, we will endeavour to investigate the full reality of God, rather than merely what philosophers consider God to be. -

Defending Existentialism?

States of Affairs, Maria Reicher, ed., (Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag 2009): 167-208. Defending Existentialism? Marian David University of Notre Dame This paper is concerned with a popular view about the nature of propositions, commonly known as the Russellian view of propositions. Alvin Plantinga has dubbed it, or more precisely, a crucial consequence of it, Existentialism, and in his paper “On Existentialism” (1983) he has presented a forceful argument intended as a reductio of this view. In what follows, I describe the main relevant ingredients of the Russellian view of propositions and states of affairs. I present a relatively simple response Russellians might want to make to Plantinga’s anti-existentialist argument. I then explore one aspect of this response—one that leads to some rather curious consequences for the Russellian view of propositions and states of affairs. 1. The Russellian View of Propositions and States of Affairs For present purposes, I take for granted that there are propositions. They are most perspicuously referred to by unadorned that-clauses, such as ‘that ants are insects’, or by what grammarians call appositive noun-phrases containing a that-clause, e.g. ‘the proposition that ants are insects’. Propositions are, as one says a bit metaphorically, the shareable contents of mental states and speech acts, such as believing, disbelieving, assuming, asserting, and denying. If I believe that ants are insects, then there is something I believe, namely (the proposition) that ants are insects. If you too believe that ants are insects, then there is something we both believe, namely (the proposition) that ants are insects. -

A Kantian Theodicy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 9 4-1-1984 A Kantian Theodicy David McKenzie Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation McKenzie, David (1984) "A Kantian Theodicy," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol1/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. A KANTIAN THEODICY David McKenzie. Since the publication of J. L. Mackie's "Evil and Omnipotence" in 1955 and especially since the publication of Alvin Plantinga's God, Freedom, and Evil in 1974, much discussion of the problem of evil has been focused on the Free Will Defense as a possible solution. Furthermore, the discussion has been oriented to what is sometimes called, 'the logical problem', namely, whether the statement that the omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good God of theism exists is consis tent with the statementthat evil exists, and not so much to the 'evidential problem' , namely, whether, even if Plantinga and others are right and these two are ulti mately consistent, the extent of the evil in our world does not undermine the ra tional justifiability of belief in God.