Anselm's Ontological Argument [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phil102: Intro to Philosophy: Knowledge & Reality

PHIL102: INTRO TO PHILOSOPHY: KNOWLEDGE & REALITY section 3, schedule #22716 MW 4:00-5:15 pm in EBA 343 Dr. Robert Francescotti Office Hours (Arts & Letters, 438): Monday 5:45–7 pm, Wednesday 12:30–1:30 pm, & Thursday 2–4 pm Office phone & e-mail: 619-594-6585, [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This course satisfies the Philosophy & Religious Studies section of the Humanities requirement of the Foundations of Learning component of the General Education requirements. - description in SDSU’s General Catalog: Introduction to philosophical inquiry with emphasis on problems of knowledge and reality. Students are encouraged to think independently and formulate their own tentative conclusions. - a fuller description of my section: You will learn about the philosophical method by exploring some main areas of philosophical interest. The first issue we will discuss is whether God exists. We will consider a few arguments designed to show that God exists along with an argument that aims to show that God does not exist. This first section of the course is a good introduction to the structure of argumentation (an essential tool of the philosophical method). Then we will investigate the Free Will debate. Science has shown that much of our behavior is the result of factors beyond our control. The environment in which we were raised obviously greatly affects our behavior. Non-conscious mental activity and genetic factors are also thought to play a major role. Of course, the state of one’s brain is a major culprit as well. However, if our actions are the result of these factors, which seem largely out of our control, then in what sense can we be considered “free”? And if we do not act in a truly free manner, then can we be held responsible for our actions? Many people believe that in addition to the body, there is some immaterial aspect to our being. -

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

An Atheistic Argument from Ugliness

AN ATHEISTIC ARGUMENT FROM UGLINESS SCOTT F. AIKIN & NICHOLAOS JONES Vanderbilt University University of Alabama in Huntsville Author posting. (c) European Journal of Philosophy of Religion 7.1 (Spring 2015). This is the author's version of the work. It is posted here for personal use, not for redistribution. The definitive version is available at http://www.philosophy-of- religion.eu/contents19.html This is a penultimate draft. Please cite only the published version. Abstract The theistic argument from beauty has what we call an ‘evil twin’, the argument from ugliness. The argument yields either what we call ‘atheist win’, or, when faced with aesthetic theodicies, ‘agnostic tie’ with the argument from beauty. 1 AN ATHEISTIC ARGUMENT FROM UGLINESS I. EVIL TWINS FOR TELEOLOGICAL ARGUMENTS The theistic argument from beauty is a teleological argument. Teleological arguments take the following form: 1. The universe (or parts of it) exhibit property X 2. Property X is usually (if not always) brought about by the purposive actions of those who created objects for them to be X. 3. The cases mentioned in Premise 1 are not explained (or fully explained) by human action 4. Therefore: The universe is (likely) the product of a purposive agent who created it to be X, namely God. The variety of teleological arguments is as broad as substitution instances for X. The standard substitutions have been features of the universe (or it all) fine-tuned for life, or the fact of moral action. One further substitution has been beauty. Thus, arguments from beauty. A truism about teleological arguments is that they have evil twins. -

On the Logic of the Ontological Argument∗ X

Paul E. Oppenheimer and Edward N. Zalta 2 by `9y(y =x)' and the claim that x has the property of existence by `E!x'. That is, we represent the difference between the two claims by exploiting the distinction between quantifying over x and predicating existence of On the Logic of the Ontological Argument∗ x. We shall sometimes refer to this as the distinction between the being of x and the existence of x. Thus, instead of reading Anselm as having discovered a way of inferring God's actuality from His mere possibility, Paul E. Oppenheimer we read him as having discovered a way of inferring God's existence from Thinking Machines Corporation His mere being. Another important feature of our reading concerns the fact that we and take the phrase \that than which none greater can be conceived" seriously. Certain inferences in the ontological argument are intimately linked to the logical behavior of this phrase, which is best represented as a definite Edward N. Zalta description.3 If we are to do justice to Anselm's argument, we must not Philosophy Department syntactically eliminate descriptions the way Russell does. One of the Stanford University highlights of our interpretation is that a very simple inference involving descriptions stands at the heart of the argument.4 Saint Anselm of Canterbury offered several arguments for the existence The Language and Logic Required for the Argument of God. We examine the famous ontological argument in Proslogium ii. Many recent authors have interpreted this argument as a modal one.1 But We shall cast our new reading in a standard first-order language. -

Thomas Aquinas' Argument from Motion & the Kalām Cosmological

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Rethinking Causality: Thomas Aquinas' Argument From Motion & the Kalām Cosmological Argument Derwin Sánchez Jr. University of Central Florida Part of the Philosophy Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Sánchez, Derwin Jr., "Rethinking Causality: Thomas Aquinas' Argument From Motion & the Kalām Cosmological Argument" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 858. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/858 RETHINKING CAUSALITY: THOMAS AQUINAS’ ARGUMENT FROM MOTION & THE KALĀM COSMOLOGICAL ARGUMENT by DERWIN SANCHEZ, JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2020 Thesis Chair: Dr. Cyrus Zargar i ABSTRACT Ever since they were formulated in the Middle Ages, St. Thomas Aquinas’ famous Five Ways to demonstrate the existence of God have been frequently debated. During this process there have been several misconceptions of what Aquinas actually meant, especially when discussing his cosmological arguments. While previous researchers have managed to tease out why Aquinas accepts some infinite regresses and rejects others, I attempt to add on to this by demonstrating the centrality of his metaphysics in his argument from motion. -

The Teleological Argument Looks at the Purpose of Something and from That

The teleological argument looks at the purpose of something and Cosmological arguments start with observations about the way The Third Way: contingency and necessity William Paley (1742 – 1805) observed that complex objects work from that he reasons that God must exist. Aquinas (1224 – 1274) the universe works and from there these try to explain why the with regularity, (seasons, gravity, etc). This order seems to be the gave five ‘ways’ of proving God exists and this, his teleological universe exists. Aquinas gives three versions of the cosmological Aquinas’ point here is that everything in the universe is result of the work of a designer who has put this regularity and arguments, starting with three different (although similar) argument, is the fifth of his five ways. contingent – it relies on something to have brought it into order into place deliberately and with purpose. For example, the observations: motion, causation and contingency. Aquinas, influenced by Aristotle, believed that all things have a existence and also things to let it continue to exist. eye is constructed perfectly to see. For Palely, all of this pointed to purpose, but we cannot achieve that purpose without something The First Way: the unmoved mover a designer, who is God. In nature, there are things that are possible ‘to be’ and to make it happen – some sort of guide, which is God. Inspired by Aristotle, Aquinas noticed that the ways in which things ‘not to be’ (contingent beings) The analogy of the watch move or change (changing state is a form of motion) must mean These things could not always have existed because that something has made that motion take place. -

God and Design: the Teleological Argument and Modern Science

GOD AND DESIGN Is there reason to think a supernatural designer made our world? Recent discoveries in physics, cosmology, and biochemistry have captured the public imagination and made the design argument—the theory that God created the world according to a specific plan—the object of renewed scientific and philosophical interest. Terms such as “cosmic fine-tuning,” the “anthropic principle,” and “irreducible complexity” have seeped into public consciousness, increasingly appearing within discussion about the existence and nature of God. This accessible and serious introduction to the design problem brings together both sympathetic and critical new perspectives from prominent scientists and philosophers including Paul Davies, Richard Swinburne, Sir Martin Rees, Michael Behe, Elliott Sober, and Peter van Inwagen. Questions raised include: • What is the logical structure of the design argument? • How can intelligent design be detected in the Universe? • What evidence is there for the claim that the Universe is divinely fine-tuned for life? • Does the possible existence of other universes refute the design argument? • Is evolutionary theory compatible with the belief that God designed the world? God and Design probes the relationship between modern science and religious belief, considering their points of conflict and their many points of similarity. Is God the “master clockmaker” who sets the world’s mechanism on a perfectly enduring course, or a miraculous presence continually intervening in and altering the world we know? Are science and faith, or evolution and creation, really in conflict at all? Expanding the parameters of a lively and urgent contemporary debate, God and Design considers the ways in which perennial questions of origin continue to fascinate and disturb us. -

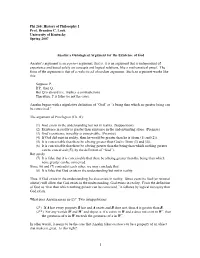

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof

Phi 260: History of Philosophy I Prof. Brandon C. Look University of Kentucky Spring 2007 Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the Existence of God Anselm’s argument is an a priori argument; that is, it is an argument that is independent of experience and based solely on concepts and logical relations, like a mathematical proof. The form of the argument is that of a reductio ad absurdum argument. Such an argument works like this: Suppose P. If P, then Q. But Q is absurd (i.e. implies a contradiction). Therefore, P is false (or not the case). Anselm begins with a stipulative definition of “God” as “a being than which no greater being can be conceived.” The argument of Proslogion (Ch. II): (1) God exists in the understanding but not in reality. (Supposition) (2) Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone. (Premise) (3) God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise) (4) If God did exist in reality, then he would be greater than he is (from (1) and (2)). (5) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than God is (from (3) and (4)). (6) It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be conceived ((5), by the definition of “God”). But surely (7) It is false that it is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which none greater can be conceived. Since (6) and (7) contradict each other, we may conclude that (8) It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality. -

Developing and Strengthening Belief in God I

DEVELOPING AND STRENGTHENING BELIEF IN GOD I First Cause (Cosmological) and Design (Teleological) Arguments he cornerstone of Jewish belief is that God created the universe ex nihilo with Tthe Torah as His Divine plan and that He continually guides and supervises His creation. Nevertheless, there are many people who do not share this belief, or at least question it. There is a need, therefore, to present a range of approaches to developing and strengthening belief in God. The traditional Jewish approach to belief in God is based on the Exodus from Egypt and hashgachah pratit (Divine Providence). These approaches are discussed in the Morasha classes on Passover, Torah M’Sinai, and Hashgachah Pratit. The goal of this series of classes is to present additional approaches to belief – those based on logic and science – to help strengthen one’s belief in God. Specifically, this series will present three arguments for the existence of God. The first class, after defining the aim of the series on the whole, will explore two deductive arguments for the existence of God, namely the First Cause or Cosmological Argument, and the Design or Teleological Argument. The second class in the series will explore the inductive approach, focusing on the Moral Argument. In order to help students digest the logical force of the arguments presented, the series will conclude with an exploration of the decision making process. In this first class we will explore the following questions: Where did the world come from? Does it make sense that the world always existed? What does modern science have to say about the subject? Does the design found in nature imply that there is a Divine Designer? Does the Theory of Evolution explain this phenomenon? 1 Core Beliefs DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING BELIEF I Class Outline: Section I. -

Divine Utilitarianism

Liberty University DIVINE UTILITARIANISM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Masters of Arts in Philosophical Studies By Jimmy R. Lewis January 16, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One: Introduction ……………………………...……………..……....3 Statement of the Problem…………………………….………………………….3 Statement of the Purpose…………………………….………………………….5 Statement of the Importance of the Problem…………………….……………...6 Statement of Position on the Problem………………………...…………….......7 Limitations…………………………………………….………………………...8 Development of Thesis……………………………………………….…………9 Chapter Two: What is meant by “Divine Utilitarianism”..................................11 Introduction……………………………….…………………………………….11 A Definition of God.……………………………………………………………13 Anselm’s God …………………………………………………………..14 Thomas’ God …………………………………………………………...19 A Definition of Utility .…………………………………………………………22 Augustine and the Good .……………………………………………......23 Bentham and Mill on Utility ……………………………………………25 Divine Utilitarianism in the Past .……………………………………………….28 New Divine Utilitarianism .……………………………………………………..35 Chapter Three: The Ethics of God ……………………………………………45 Divine Command Theory: A Juxtaposition .……………………………………45 What Divine Command Theory Explains ………………….…………...47 What Divine Command Theory Fails to Explain ………………………47 What Divine Utilitarianism Explains …………………………………………...50 Assessing the Juxtaposition .…………………………………………………....58 Chapter Four: Summary and Conclusion……………………………………...60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..64 2 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Statement of the -

First Prize: an Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield

Philsoc Student Essay Prize, Michaelmas Term 2015 First Prize: An Analysis of the Ontological Argument of St Anselm by Ian Corfield Introduction St Anselm (1033CE-1109CE) was a philosopher and theologian and held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093CE until his death. He is remembered chiefly as the originator of the first ‘Ontological Argument’ for the existence of God. Ontological Arguments1 are a priori2 arguments purporting to establish the existence of God from the very definition of the same. Many such arguments have been advanced since Anselm’s, but Anselm’s original argument has remained a popular object of study. The Argument Anselm’s argument is set out in the second chapter of his work ‘The Proslogion’: And so, O Lord, … give me to understand … that thou art … a being than which none greater3 can be thought. Or can it be that there is no such being, since “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘There is no God’”? [Psalms 14.1; 53.1] But … this same fool … must be convinced that a being than which none greater can be thought exists at least in his understanding… . But clearly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is actually in the understanding alone, it can be thought of as existing also in reality, and this is greater. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the understanding alone, this same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. -

The Design Argument

The design argument The different versions of the cosmological argument we discussed over the last few weeks were arguments for the existence of God based on extremely abstract and general features of the universe, such as the fact that some things come into existence, and that there are some contingent things. The argument we’ll be discussing today is not like this. The basic idea of the argument is that if we pay close attention to the details of the universe in which we live, we’ll be able to see that that universe must have been created by an intelligent designer. This design argument, or, as its sometimes called, the teleological argument, has probably been the most influential argument for the existence of God throughout most of history. You will by now not be surprised that a version of the teleological argument can be found in the writings of Thomas Aquinas. You will by now not be surprised that a version of the teleological argument can be found in the writings of Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas is noting that things we observe in nature, like plants and animals, typically act in ways which are advantageous to themselves. Think, for example, of the way that many plants grow in the direction of light. Clearly, as Aquinas says, plants don’t do this because they know where the light is; as he says, they “lack knowledge.” But then how do they manage this? What does explain the fact that plants grow in the direction of light, if not knowledge? Aquinas’ answer to this question is that they must be “directed to their end” -- i.e., designed to be such as to grow toward the light -- by God.