The Design Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Intelligent Design Creationist Movement: Its True Nature and Goals

UNDERSTANDING THE INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONIST MOVEMENT: ITS TRUE NATURE AND GOALS A POSITION PAPER FROM THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY OFFICE OF PUBLIC POLICY AUTHOR: BARBARA FORREST, Ph.D. Reviewing Committee: Paul Kurtz, Ph.D.; Austin Dacey, Ph.D.; Stuart D. Jordan, Ph.D.; Ronald A. Lindsay, J. D., Ph.D.; John Shook, Ph.D.; Toni Van Pelt DATED: MAY 2007 ( AMENDED JULY 2007) Copyright © 2007 Center for Inquiry, Inc. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the Center for Inquiry, Inc. Table of Contents Section I. Introduction: What is at stake in the dispute over intelligent design?.................. 1 Section II. What is the intelligent design creationist movement? ........................................ 2 Section III. The historical and legal background of intelligent design creationism ................ 6 Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) ............................................................................ 6 McLean v. Arkansas (1982) .............................................................................. 6 Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) ............................................................................. 7 Section IV. The ID movement’s aims and strategy .............................................................. 9 The “Wedge Strategy” ..................................................................................... -

Ono Mato Pee 145

789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 9 789493 148215 789493 9 9 789493 148215 9 148215 789493 148215 789493 9 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 789493 9 789493 148215 9 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 145 PEE MATO ONO Graphic Design Systems, and the Systems of Graphic Design Francisco Laranjo Bibliography M.; Drenttel, W. & Heller, S. (2012) Within graphic design, the concept of systems is profoundly Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings rooted in form. When a term such as system is invoked, it is the Pluriverse (New Ecologies for on Graphic Design. Allworth Press, normally related to macro and micro-typography, involving pp. 199–207. the Twenty-First Century). Duke book design and typesetting, but also addressing type design University Press. Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When or parametric typefaces. Branding and signage are two other Jenner, K. (2016) Chill Kendall Jenner Everybody Designs: An Introduction Didn’t Think People Would Care to Design for Social Innovation. domains which nearly claim exclusivity of the use of the That She Deleted Her Instagram. Massachusetts: MIT Press. word ‘systems’ in relation to graphic design. A key example of In: Vogue. Available at: https://www. Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in this is the influential bookGrid Systems in Graphic Design vogue.com/article/kendall-jenner- Systems. -

An Atheistic Argument from Ugliness

AN ATHEISTIC ARGUMENT FROM UGLINESS SCOTT F. AIKIN & NICHOLAOS JONES Vanderbilt University University of Alabama in Huntsville Author posting. (c) European Journal of Philosophy of Religion 7.1 (Spring 2015). This is the author's version of the work. It is posted here for personal use, not for redistribution. The definitive version is available at http://www.philosophy-of- religion.eu/contents19.html This is a penultimate draft. Please cite only the published version. Abstract The theistic argument from beauty has what we call an ‘evil twin’, the argument from ugliness. The argument yields either what we call ‘atheist win’, or, when faced with aesthetic theodicies, ‘agnostic tie’ with the argument from beauty. 1 AN ATHEISTIC ARGUMENT FROM UGLINESS I. EVIL TWINS FOR TELEOLOGICAL ARGUMENTS The theistic argument from beauty is a teleological argument. Teleological arguments take the following form: 1. The universe (or parts of it) exhibit property X 2. Property X is usually (if not always) brought about by the purposive actions of those who created objects for them to be X. 3. The cases mentioned in Premise 1 are not explained (or fully explained) by human action 4. Therefore: The universe is (likely) the product of a purposive agent who created it to be X, namely God. The variety of teleological arguments is as broad as substitution instances for X. The standard substitutions have been features of the universe (or it all) fine-tuned for life, or the fact of moral action. One further substitution has been beauty. Thus, arguments from beauty. A truism about teleological arguments is that they have evil twins. -

The Utilitarian Influence on American Legal Science in the Early Republic

1 The Utilitarian Influence on American Legal Science in the Early Republic Steven J. Macias California Western School of Law [email protected] (rev. 9/8) In Utilitarian Jurisprudence in America, Peter King held up Thomas Cooper, David Hoffman, and Richard Hildreth, as those early American legal thinkers most notably influenced by Bentham.1 For King, Hildreth represented “the first real fruition of Benthamism in America,” whereas Cooper’s use of Bentham was subservient to his Southern ideology, and Hoffman’s use was mainly to “reinforce” a utilitarianism otherwise “derived from Paley.”2 Although Hildreth’s work falls outside the timeframe of early-American legal science, Cooper’s and Hoffman’s work falls squarely within it. What follows is, in part, a reevaluation of Cooper and Hoffman within the broader context of early republican jurisprudence. Because Cooper became an advocate of southern secession late in life, too many historians have dismissed his life’s work, which consisted of serious intellectual undertakings in law and philosophy, as well as medicine and chemistry. Hoffman, on the other hand, has become a man for all seasons among legal historians. His seven-year course of legal study contained such a vast and eclectic array of titles, that one can superficially paint Hoffman as advocating just about anything. As of late, Hoffman has been discussed as a leading exponent of Scottish Common Sense philosophy, second only to James Wilson a generation earlier. This tension between Hoffman-the-utilitarian and Hoffman-the-Scot requires a new examination. A fresh look at the utilitarian influence on American jurisprudence also requires that we acknowledge 1 PETER J. -

Thomas Aquinas' Argument from Motion & the Kalām Cosmological

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Rethinking Causality: Thomas Aquinas' Argument From Motion & the Kalām Cosmological Argument Derwin Sánchez Jr. University of Central Florida Part of the Philosophy Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Sánchez, Derwin Jr., "Rethinking Causality: Thomas Aquinas' Argument From Motion & the Kalām Cosmological Argument" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 858. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/858 RETHINKING CAUSALITY: THOMAS AQUINAS’ ARGUMENT FROM MOTION & THE KALĀM COSMOLOGICAL ARGUMENT by DERWIN SANCHEZ, JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2020 Thesis Chair: Dr. Cyrus Zargar i ABSTRACT Ever since they were formulated in the Middle Ages, St. Thomas Aquinas’ famous Five Ways to demonstrate the existence of God have been frequently debated. During this process there have been several misconceptions of what Aquinas actually meant, especially when discussing his cosmological arguments. While previous researchers have managed to tease out why Aquinas accepts some infinite regresses and rejects others, I attempt to add on to this by demonstrating the centrality of his metaphysics in his argument from motion. -

Arguments from Design

Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Victoria S. Harrison University of Glasgow This is an archived version of ‘Arguments form Design: A Self-defeating Strategy?’, published in Philosophia 33 (2005): 297–317. Dr V. Harrison Department of Philosophy 69 Oakfield Avenue University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8LT Scotland UK E-mail: [email protected] Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Abstract: In this article, after reviewing traditional arguments from design, I consider some more recent versions: the so-called ‘new design arguments’ for the existence of God. These arguments enjoy an apparent advantage over the traditional arguments from design by avoiding some of Hume’s famous criticisms. However, in seeking to render religion and science compatible, it seems that they require a modification not only of our scientific understanding but also of the traditional conception of God. Moreover, there is a key problem with arguments from design that Mill raised to which the new arguments seem no less vulnerable than the older versions. The view that science and religion are complementary has at least one significant advantage over other positions, such as the view that they are in an antagonistic relationship or the view that they are so incommensurable that they are neither complementary nor antagonistic. The advantage is that it aspires to provide a unified worldview that is sensitive to the claims of both science and religion. And surely, such a worldview, if available, would seem to be superior to one in which, say, scientific and religious claims were held despite their obvious contradictions. -

The Teleological Argument Looks at the Purpose of Something and from That

The teleological argument looks at the purpose of something and Cosmological arguments start with observations about the way The Third Way: contingency and necessity William Paley (1742 – 1805) observed that complex objects work from that he reasons that God must exist. Aquinas (1224 – 1274) the universe works and from there these try to explain why the with regularity, (seasons, gravity, etc). This order seems to be the gave five ‘ways’ of proving God exists and this, his teleological universe exists. Aquinas gives three versions of the cosmological Aquinas’ point here is that everything in the universe is result of the work of a designer who has put this regularity and arguments, starting with three different (although similar) argument, is the fifth of his five ways. contingent – it relies on something to have brought it into order into place deliberately and with purpose. For example, the observations: motion, causation and contingency. Aquinas, influenced by Aristotle, believed that all things have a existence and also things to let it continue to exist. eye is constructed perfectly to see. For Palely, all of this pointed to purpose, but we cannot achieve that purpose without something The First Way: the unmoved mover a designer, who is God. In nature, there are things that are possible ‘to be’ and to make it happen – some sort of guide, which is God. Inspired by Aristotle, Aquinas noticed that the ways in which things ‘not to be’ (contingent beings) The analogy of the watch move or change (changing state is a form of motion) must mean These things could not always have existed because that something has made that motion take place. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

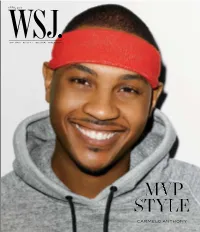

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?

Leaven Volume 17 Issue 2 Theology and Science Article 6 1-1-2009 Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Chris Doran [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Doran, Chris (2009) "Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?," Leaven: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol17/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Doran: Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? CHRIS DORAN imaginethatwe have all had occasion to look up into the sky on a clear night, gaze at the countless stars, and think about how small we are in comparison to the enormity of the universe. For everyone except Ithe most strident atheist (although I suspect that even s/he has at one point considered the same feeling), staring into space can be a stark reminder that the universe is much grander than we could ever imagine, which may cause us to contemplate who or what might have put this universe together. For believers, looking up at tJotestars often puts us into the same spirit of worship that must have filled the psalmist when he wrote, "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands" (Psalms 19.1). -

Intelligent Design Is Not Science” Given by John G

An Outline of a lecture entitled, “Intelligent Design is not Science” given by John G. Wise in the Spring Semester of 2007: Slide 1 Why… … do humans have so much trouble with wisdom teeth? … is childbirth so dangerous and painful? Because a big, thinking brain is an advantage, and evolution is imperfect. Slide 2 Charles Darwin’s Revolutionary Idea His book changed the world. All life forms on this planet are related to each other through “Descent with modification over generations from a common ancestor”. Natural processes fully explain the biological connections between all life on the planet. Slide 3 Darwin’s Idea is Dangerous (from the book of the same title by Daniel Dennett) If we have evolution, we no longer need a Creator to create each and every species. Darwinism is dangerous because it infers that God did not directly and purposefully create us. It simply states that we evolved. Slide 4 Intelligent Design Attempts to Counter Darwin “Intelligent Design” has been proposed as way out of this dilemma. – Phillip Johnson, William Dembski, and Michael Behe (to name a few). They attempt to redefine science to encompass the supernatural as well as the natural world. They accept Darwin’s evolution, if an Intelligent Designer is (sometimes) substituted for natural selection. Design arguments are not new: − 1250 - St. Thomas Aquinas - first design argument − 1802 - Natural Theology - William Paley – perhaps the best(?) design argument Slide 5 What is Science? A specific way of understanding the natural world. Based on the idea that our senses give us accurate information about the Universe. -

Theories of Non-Productivity in Victorian Contexts This Dissertation

1 Chapter One Impossible Economies: Theories of Non-Productivity in Victorian Contexts This dissertation is about a set of key paradoxes in Victorian thought. In general terms, it defines a series of interlocking mental habits at mid-century, and maps the diverse deployments of those habits in contemporary locations of knowledge. My focus resides with several formative scientific studies that I read alongside parallel developments in the realist novel, moral philosophy, and social critique. But my main purpose in doing so is not to re-construct the lines of a distinct disciplinary formation so much as to recover a richer range of cultural confluences and epistemic patterns. More precisely, I discuss the ways in which major Victorian texts understood the shifting boundaries between the individual and the group—and, namely, the breakdown of cooperative bonds. Whereas older norms of natural explanation had emphasized the reciprocal relationship between part and whole, in keeping with the watch-like regularities promulgated by natural theology, these texts turned time after time to the function of the prodigal part--the exception that failed to signify within the larger life of the group. This emphasis held equally true in theories of human bodies, of communities, and of the created cosmos at large. To inquire into the natural order, in this context, was to note the recurrence of those elements which were wasteful or otherwise non- productive within the orderly operations of the whole. The paradoxes that emerged 2 among this state of affairs, and their relation to the formal and perspectival patterns of the novel, form my central concerns in the chapters to follow. -

Theological Utilitarianism and the Eclipse of the Theistic Sanction

Tyndale Bulletin 42.2 (Nov. 1991) 226-244. THEOLOGICAL UTILITARIANISM AND THE ECLIPSE OF THE THEISTIC SANCTION Graham Cole Utilitarianism as a moral philosophy ‘is essentially English’, and, ‘constitutes the largest contribution made by the English to moral and political theory’, according to Oxford philosopher John Plamenatz.1 Although there were similar philosophies on the Continent at the time, for Plamenatz the four great utilitarians remain Hume, Bentham, James Mill and his son, John Stuart Mill. (What the Scot David Hume may have thought of being included amongst the English, Plamenatz does not pause to consider). Still others have pointed out that utilitarian moral theory is of no mere antiquarian concern, but represents a living philosophical tradition.2 Indeed, Alan Ryan describes it as ‘the best known of all moral theories’.3 Theological utilitarianism, on the other hand, is not a living philosophical tradition. Its last great exponent, William Paley, died in 1805. If it is mentioned at all by scholars and its history rehearsed, then the object is to set the scene for Bentham and Mill. After that the category becomes otiose. Indeed some scholars do not employ the expression ‘theological utilitarianism’ at all in their discussions of the period, and others, if they do, they do so in a highly qualified way.4 However, as a tradition of moral thought 1John Plamenataz, The English Utilitarians, (Oxford 1949) 1-2. 2Anthony Quinton, Utilitarian Ethics, (London & Basingstoke 1973) for a useful account. 3See his introduction to Utilitarianism and other Essays: John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham (Harmondsworth 1987) 7. 4The Encyclopaedia of Philosophy provides a good illustration.