Manning the High Seat: Seiðr As Self- Making in Contemporary Norse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Train Your Dragon: Pre‐Reading

How to Train Your Dragon: Pre‐reading Social & Historical Context When we study English at secondary level, it is often useful to find out about the social and historical contexts that surround what we are reading. We look at the key events in history and society that took place during the time a text was written or set. We then question how this context may have influenced the presentation of: events, characters and ideas. ‘How to Train Your Dragon,’ was published in 2003 but it is set on the fictional island of Berk during the age of the Vikings. Before we start reading the novel, let’s explore some context. Read the contextual information and complete the activities below. Who were the Vikings? The Vikings, also called Norsemen, came from all around Scandinavia (where Norway, Sweden and Denmark are today). They sent armies to Britain about the year 700 AD to take over some of the land, and they lived here until around 1050. Even though the Vikings didn’t stay in Britain, they left a strong mark on society – we’ve even kept some of the same names of towns. They had a large settlement around York and the Midlands, and you can see some of the artefacts from Viking settlements today. The word ‘Viking’ means ‘a pirate raid’ in the Norse language, which is what the Vikings spoke. Some of the names of our towns and villages have a little bit of Norse language in them. Do you recognise any names with endings like these: ‘‐by’ (as in Corby or Whitby, means ‘farm’ or ‘town’) and ‘‐thorpe’ (as in Scunthorpe) means ‘village.’ The Viking alphabet, ‘Futhark’, was made up of 24 characters called runes. -

Nú Mun Hon Sökkvask

Lauren Hamm Kt. 290191-5219 MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Autumn 2019 Nú mun hon sökkvask: The Connection between Prophetic Magic and the Feminine in Old Nordic Religion Lauren Hamm Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Útskriftarmánuður: Október 2019 Lauren Hamm Kt. 290191-5219 MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Autumn 2019 Nú mun hon sökkvask The Connection between Prophetic Magic and the Feminine in Old Nordic Religion Lauren Hamm Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags - og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október 2019 Lauren Hamm Kt. 290191-5219 MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Autumn 2019 Nú mun hon sökkvask: The Connection between Prophetic Magic and the Feminine in Old Nordic Religion Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA – gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Lauren Hamm, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Lauren Hamm Kt. 290191-5219 MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Autumn 2019 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible if it were not for the endless kindness and patience of my thesis advisor, Dr. Terry Gunnell. I truly do not have words eloquent enough to iterate how very much he deeply cares about his work and the work of his students nor how much this meant to me personally. The year of waking up to 6:00 AM skype meetings every Tuesday with Terry provided a gentle reminder of my duties and passion for this topic as well as a sense of stability and purpose I badly needed during a tumultuous time in my life. -

University of London Deviant Burials in Viking-Age

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA Ruth Lydia Taylor M. Phil, Institute of Archaeology, University College London UMI Number: U602472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602472 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA The thesis brings together information yielded from archaeology and other sources to provide an overall picture of the types of burial practices encountered during the Viking-Age in Scandinavia. From this, an attempt is made to establish deviancy. Comparative evidence, such as literary, runic, legal and folkloric evidence will be used critically to shed perspective on burial practices and the artefacts found within the graves. The thesis will mostly cover burials from the Viking Age (late 8th century to the mid- 11th century), but where the comparative evidence dates from other periods, its validity is discussed accordingly. Two types of deviant burial emerged: the criminal and the victim. A third type, which shows distinctive irregularity yet lacks deviancy, is the healer/witch burial. -

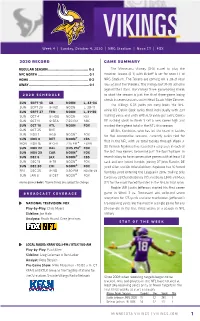

VIKINGS 2020 Vikings

VIKINGS 2020 vikings Week 4 | Sunday, October 4, 2020 | NRG Stadium | Noon CT | FOX 2020 record game summary REGULAR SEASON......................................... 0-3 The Minnesota Vikings (0-3) travel to play the NFC NORTH ....................................................0-1 Houston Texans (0-3) with kickoff is set for noon CT at HOME ............................................................ 0-2 NRG Stadium. The Texans are coming off a 28-21 road AWAY .............................................................0-1 loss against the Steelers. The Vikings lost 31-30 at home against the Titans. The Vikings three-game losing streak 2020 schedule to start the season is just the third three-game losing streak in seven seasons under Head Coach Mike Zimmer. sun sept 13 gb noon l, 43-34 The Vikings 6.03 yards per carry leads the NFL, sun sept 20 @ ind noon l, 28-11 sun sept 27 ten noon l, 31-30 while RB Dalvin Cook ranks third individually with 294 sun oct 4 @ hou noon fox rushing yards and sixth with 6.13 yards per carry. Cook’s sun oct 11 @ sea 7:20 pm nbc 181 rushing yards in Week 3 set a new career high and sun oct 18 atl noon fox marked the highest total in the NFL this season. sun oct 25 bye LB Eric Kendricks, who has led the team in tackles sun nov 1 @gb noon* fox for five consecutive seasons, currently ranks tied for sun nov 8 det noon* cbs first in the NFL with 33 total tackles through Week 3. mon nov 16 @ chi 7:15 pm* espn sun nov 22 dal 3:25 pm* fox DE Yannick Ngakoue has recorded a strip sack in each of sun nov 29 car noon* fox the last two games, becoming just the fourth player in sun dec 6 jax noon* cbs team history to have consecutive games with at least 1.0 sun dec 13 @ tb noon* fox sack and one forced fumble, joining DT John Randle, DE sun dec 20 chi noon* fox Jared Allen and DE Brian Robison. -

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

History Channel's Fact Or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion Gypsey Teague Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 10-31-2015 The iV kings: History Channel's Fact or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion Gypsey Teague Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Teague, Gypsey, "The iV kings: History Channel's Fact or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion" (2015). Presentations. 60. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/60 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Vikings: History Channel’s Fact or Fictionalized View of The Norse Expansion Presented October 31, 2015 at the New England Popular Culture Association, Colby-Sawyer College, New London, NH ABSTRACT: The History Channel’s The Vikings is a fictionalized history of Ragnar Lothbrok who during the 8th and 9th Century traveled and raided the British Isles and all the way to Paris. This paper will look at the factual Ragnar and the fictionalized character as presented to the general viewing public. Ragnar Lothbrok is getting a lot of air time recently. He and the other characters from the History Channel series The Vikings are on Tee shirts, posters, books, and websites. The jewelry from the series is selling quickly on the web and the actors that portray the characters are in high demand at conventions and other venues. The series is fun but as all historic series creates a history that is not necessarily accurate. -

Tarot Reading Style: Healer Tarot Reading Style: Healing

Tarot Reading Style: Healer Tarot Reading Style: Healing USING YOUR NATURAL GIFTS & ABILITIES... You help people connect with the core energy of their obstacles and shift them into opportunities. You help them find tools to heal from the pain carried around from past relationships and situations. YOUR GREATEST TOOL IN TAROT READING IS... Resolving Past Issues In your readings, you bring focus and awareness to bringing harmony, balance, and alignment to all levels of being (mind, body, & spirit) and help your clients move through past blocks and baggage. Major Arcana Archetype Temperance Temperance reminds us that real change takes time ,A person's ability to exercise patience, balance, and self-control are infinite virtues. Temperance represents someone who has a patient, harmonious approach to life and understands the value of compromise. A READER WITH THIS ARCHETYPE: ... is able to guide people into a place of healing, where they begin to release the past. Because of their natural gift for diplomacy, they tend to be excellent communicators who bring out the best in their clients and friends. They could be holistic healers or have other psychic abilities and are able to combine different aspects of any modality in order to create something new and fresh. Your Strengths Healing HEALERS HAVE A NATURAL TALENT FOR SEEING 'CAUSE & EFFECT' ... Highlighting Connecting Patterns & Symptoms Limiting to Beliefs Experiences Easily See How It Plays Out In Clients Lives ... You focus on creating balance and harmony in your clients lives. ... You help them move out of the past by helping them revise and reframe it. ... You honor your clients pain and create the space for them to move through it. -

The Vikings Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE VIKINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Else Roesdahl | 352 pages | 01 Jan 1999 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140252828 | English | London, United Kingdom The Vikings PDF Book Young men were expected to test themselves in this manner. Roam Robotics, a small business located in San Francisco, California, has developed a lightweight and inexpensive knee exoskeleton for Still, Leif established new colonies and even traded with the natives. If a dispute could not be settled, they often resorted to duels or torturous trials known as ordeals [source: Wolf ]. It's best used at 36 points and above to really appreciate the details. And who can blame her? Lagertha Katheryn Winnick , the first wife of Ragnar Lothbrok Travis Fimmel , made quite a name for herself throughout the series. We'll look at the military and nonmilitary technology used by the Vikings in the next section. An elected or appointed official known as a law-speaker acted as an impartial judge to guide the meetings. During Operation Enduring Freedom in late and throughout , forward- deployed S-3B Viking tankers flew more than percent over their normal flight hours underway, enabling air wing strike fighters to reach their assigned kill boxes and return safely to the aircraft carrier from Afghanistan. Sortie rates of 30 missions a day were not uncommon for squadrons operating from carriers in the eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. No whispering over ale in the Great Hall; it's all shouting with this boisterous crew. It is unknown how many real berserkers existed -- they show up most frequently in Nordic sagas as powerful foils for the heroic protagonist [source: Haywood ]. -

Festivalpuljen 2022 Resumeer Af Ansøgninger Indkommet Den 15

Festivalpuljen 2022 Resumeer af ansøgninger indkommet den 15. maj 2021 Kategori Ansøger 1 . Musik Andrea Lonardo 1. Musik Colossal v. Jens Back 1. Musik Barefoot Records 1. Musik Foreningen af Blågårds Plads 1. Musik JAZZiVÆRK v. forperson Mai Seidelin 1. Musik Koncertforeningen Copenhagen Concert Community 1. Musik 5 Copenhagen Summer Festival 1. Musik Live Nation 1. Musik Nus/Nus ApS 1. Musik Musikforeningen Loppen 1. Musik Adreas Korsgaard Rasusse – Det regioale spillested ALICE står, på vegne af en nystartet, selvstændig forening, som ansøger. 1. Musik Journey 1. Musik Foreningen KLANG - Copenhagen Avantgarde Music Festival 1. Musik The Big Oil Media Group S.M.B.A. 1. Musik NJORD Festival 1. Musik Foreningen Roots & Jazz 1. Musik Foreningen Cap30 1. Musik Sound21 1. Musk Foreningen Copenhagen World Music Festival 2. Billedkunst Samarbejdet mellem Den Frie Udstillingsbygning, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Nikolaj Kunsthal, Kunstforeningen GL. STRAND, Overgaden og Copenhagen Contemporary v. Kunsthal Charlottenborg 2. Billedkunst Jan Falk Borup 2. Billedkunst Chart Festival 2. Billedkunst Copenhagen Photo Festival 2. Billedkunst TAP1 3. Scenekunst Copenhagen Dream House/100 Dansere 3. Scenekunst Frivillig forening CLASHcph 3. Scenekunst Børekulturhus Aa’r e del af Køehas Koue 3. Scenekunst Copenhagen Circus Arts Festival 3. Scenekunst Mai Seidelin og Johan Bylling Lang (fra 2022 Foreningen Copenhagen Harbour Parade) 3. Scenekunst Copenhagen Dance Arts (CDA) Kunstnerisk ledelse; Lotte Sigh & Morten Innstrand 3. Scenekunst Copenhagen Opera Festival, Chefproducent, Rikke Frisk 3. Scenekunst CPH Stage 3. Scenekunst Foreningen Teater Solaris 3. Scenekunst AFUK 3. Scenekunst Foreningen Cap30 3. Scenekunst Nordic Break 3. Scenekunst Puppet Junior Festival ved Børnekulturstedet Sokkelundlille 3. Scenekunst Danseatelier 4. -

Copyright © 2010 Witch Supercenter – October Newsletter in This Issue Important October Dates Witch

October Newsletter In this Issue Important October Dates Witch SuperCenter October Sale Items Herb of the Month – Rosemary Stone of the Month – Red Jasper Rune of the Month – Thurisaz Tarot Card of the Month – Justice Correspondence of the Month – Mythical Creatures Spell of the Month – Astral Projection Important October Dates (All times are CST) October 7, 1:45 pm - New Moon New Moons signify rebirth, beginnings, a clean slate, the start of a new cycle. This new moon highlights Sagittarian qualities (idealistic, optimistic, good-humored, opportunistic, intelligent) and 9th house themes (personal growth, spirituality, travel, higher education). This is a time of optimism and dreams; the moon seeks knowledge. New Moons are times of new beginnings, and this New Moon offers the potential of a brand new understanding of what gives our life meaning. To move in the direction of Sagittarius truth always requires a leap of faith and confidence in what we know. In pursuing this path, there's the danger of becoming insular and overzealous, of refusing to listen at all to other points of view. The utter conviction that serves Sagittarius so well in many situations can sometimes cause problems if we assume our own truth is universal. Navigating the Sagittarius experience requires that we keep feeding our brains with other ideas and perspectives, to keep ourselves flexible and lively. But for the sake of innovation, it's equally important to know when to escape to our own imaginations and retrieve what we find there.This expansion of our sense of what is possible and what is correct is what the Sagittarian New Moon inspires. -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free

Issue 63: How the Vikings Took up the Faith Conversion of the Vikings: Did You Know? Fascinating and little-known facts about the Vikings and their times. What's a Viking? To the Franks, they were Northmen or Danes (no matter if they were from Denmark or not). The English called them Danes and heathens. To the Irish, they were pagans. Eastern Europe called them the Rus. But the Norse term is the one that stuck: Vikings. The name probably came from the Norse word vik, meaning "bay" or "creek," or from the Vik area, the body of water now called Skagerrak, which sits between Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. In any case, it probably first referred only to the raiders (víkingr means pirate) and was later applied to Scandinavians as a whole between the time of the Lindesfarne raid (793) and the Battle of Hastings (1066). Thank the gods it's Frigg's day. Though Vikings have a reputation for hit-and-run raiding, Vikings actually settled down and influenced European culture long after the fires of invasion burned out. For example, many English words have roots in Scandinavian speech: take, window, husband, sky, anger, low, scant, loose, ugly, wrong, happy, thrive, ill, die, beer, anchor. … The most acute example is our days of the week. Originally the Romans named days for the seven most important celestial bodies (sun, moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn). The Anglo-Saxons inserted the names of some Norse deities, by which we now name Tuesday through Friday: the war god Tiw (Old English for Tyr), Wodin (Odin), Thor, and fertility goddess Frigg. -

A Viking Encounter’ the Vikings Came from the Scandinavian Countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark

Map of Viking Routes Year Five – ‘A Viking Encounter’ The Vikings came from the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark. The time between 787AD and 1050AD is known as the time of the Vikings. Initially, they settled in northern Scotland and eastern England, also establishing the city of Dublin in Ireland. Around 1000AD, some Vikings settled in North America, but did not stay long. They also travelled to southern Spain and Russia, and traded as far away as Turkey. ‘A Viking Encounter’ Useful Websites https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/ztyr9j6 https://www.jorvikvikingcentre.co.uk/ https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/discover/history/general-history/10- facts-about-the-vikings/ https://www.funkidslive.com/learn/top-10-facts-about-vikings/# https://www.dkfindout.com/uk/history/vikings/ Were the Vikings victorious or simply vicious? –The 840 AD – Viking – Danish Vikings 878-886 AD– King Alfred divides 900-911 AD – The Vikings 787-789 AD 866 AD Vikings begin their settlers establish the city of establish a kingdom in England under the Danelaw Act, raid the Mediterranean, and attacks on Britain. Dublin in Ireland. York, England. granting Vikings north & east England. found Normandy in France. Ragnar Lodbrok (740/780-840 AD) Ivar the Boneless (794-873 AD) Erik the Red (950AD-1003AD) Ragnar Ladbrok is a legendary Danish and Swedish Viking leader, who is Ivar the Boneless was a notoriously Erik Thorvaldsson, known as Erik the Red, was a largely known from Viking Age Old ferocious Viking leader and commander Norse explorer, famed for having founded the Norse poetry and literature (there is who invaded what is now England.