JOANNA KATARZYNA PUCHALSKA* Vikings Television Series: When

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Train Your Dragon: Pre‐Reading

How to Train Your Dragon: Pre‐reading Social & Historical Context When we study English at secondary level, it is often useful to find out about the social and historical contexts that surround what we are reading. We look at the key events in history and society that took place during the time a text was written or set. We then question how this context may have influenced the presentation of: events, characters and ideas. ‘How to Train Your Dragon,’ was published in 2003 but it is set on the fictional island of Berk during the age of the Vikings. Before we start reading the novel, let’s explore some context. Read the contextual information and complete the activities below. Who were the Vikings? The Vikings, also called Norsemen, came from all around Scandinavia (where Norway, Sweden and Denmark are today). They sent armies to Britain about the year 700 AD to take over some of the land, and they lived here until around 1050. Even though the Vikings didn’t stay in Britain, they left a strong mark on society – we’ve even kept some of the same names of towns. They had a large settlement around York and the Midlands, and you can see some of the artefacts from Viking settlements today. The word ‘Viking’ means ‘a pirate raid’ in the Norse language, which is what the Vikings spoke. Some of the names of our towns and villages have a little bit of Norse language in them. Do you recognise any names with endings like these: ‘‐by’ (as in Corby or Whitby, means ‘farm’ or ‘town’) and ‘‐thorpe’ (as in Scunthorpe) means ‘village.’ The Viking alphabet, ‘Futhark’, was made up of 24 characters called runes. -

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

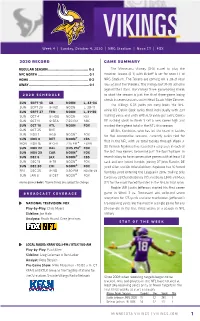

VIKINGS 2020 Vikings

VIKINGS 2020 vikings Week 4 | Sunday, October 4, 2020 | NRG Stadium | Noon CT | FOX 2020 record game summary REGULAR SEASON......................................... 0-3 The Minnesota Vikings (0-3) travel to play the NFC NORTH ....................................................0-1 Houston Texans (0-3) with kickoff is set for noon CT at HOME ............................................................ 0-2 NRG Stadium. The Texans are coming off a 28-21 road AWAY .............................................................0-1 loss against the Steelers. The Vikings lost 31-30 at home against the Titans. The Vikings three-game losing streak 2020 schedule to start the season is just the third three-game losing streak in seven seasons under Head Coach Mike Zimmer. sun sept 13 gb noon l, 43-34 The Vikings 6.03 yards per carry leads the NFL, sun sept 20 @ ind noon l, 28-11 sun sept 27 ten noon l, 31-30 while RB Dalvin Cook ranks third individually with 294 sun oct 4 @ hou noon fox rushing yards and sixth with 6.13 yards per carry. Cook’s sun oct 11 @ sea 7:20 pm nbc 181 rushing yards in Week 3 set a new career high and sun oct 18 atl noon fox marked the highest total in the NFL this season. sun oct 25 bye LB Eric Kendricks, who has led the team in tackles sun nov 1 @gb noon* fox for five consecutive seasons, currently ranks tied for sun nov 8 det noon* cbs first in the NFL with 33 total tackles through Week 3. mon nov 16 @ chi 7:15 pm* espn sun nov 22 dal 3:25 pm* fox DE Yannick Ngakoue has recorded a strip sack in each of sun nov 29 car noon* fox the last two games, becoming just the fourth player in sun dec 6 jax noon* cbs team history to have consecutive games with at least 1.0 sun dec 13 @ tb noon* fox sack and one forced fumble, joining DT John Randle, DE sun dec 20 chi noon* fox Jared Allen and DE Brian Robison. -

History Channel's Fact Or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion Gypsey Teague Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 10-31-2015 The iV kings: History Channel's Fact or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion Gypsey Teague Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Teague, Gypsey, "The iV kings: History Channel's Fact or Fictionalized View of the Norse Expansion" (2015). Presentations. 60. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/60 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Vikings: History Channel’s Fact or Fictionalized View of The Norse Expansion Presented October 31, 2015 at the New England Popular Culture Association, Colby-Sawyer College, New London, NH ABSTRACT: The History Channel’s The Vikings is a fictionalized history of Ragnar Lothbrok who during the 8th and 9th Century traveled and raided the British Isles and all the way to Paris. This paper will look at the factual Ragnar and the fictionalized character as presented to the general viewing public. Ragnar Lothbrok is getting a lot of air time recently. He and the other characters from the History Channel series The Vikings are on Tee shirts, posters, books, and websites. The jewelry from the series is selling quickly on the web and the actors that portray the characters are in high demand at conventions and other venues. The series is fun but as all historic series creates a history that is not necessarily accurate. -

The Vikings Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE VIKINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Else Roesdahl | 352 pages | 01 Jan 1999 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140252828 | English | London, United Kingdom The Vikings PDF Book Young men were expected to test themselves in this manner. Roam Robotics, a small business located in San Francisco, California, has developed a lightweight and inexpensive knee exoskeleton for Still, Leif established new colonies and even traded with the natives. If a dispute could not be settled, they often resorted to duels or torturous trials known as ordeals [source: Wolf ]. It's best used at 36 points and above to really appreciate the details. And who can blame her? Lagertha Katheryn Winnick , the first wife of Ragnar Lothbrok Travis Fimmel , made quite a name for herself throughout the series. We'll look at the military and nonmilitary technology used by the Vikings in the next section. An elected or appointed official known as a law-speaker acted as an impartial judge to guide the meetings. During Operation Enduring Freedom in late and throughout , forward- deployed S-3B Viking tankers flew more than percent over their normal flight hours underway, enabling air wing strike fighters to reach their assigned kill boxes and return safely to the aircraft carrier from Afghanistan. Sortie rates of 30 missions a day were not uncommon for squadrons operating from carriers in the eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. No whispering over ale in the Great Hall; it's all shouting with this boisterous crew. It is unknown how many real berserkers existed -- they show up most frequently in Nordic sagas as powerful foils for the heroic protagonist [source: Haywood ]. -

an Examination of the Relationship Between the Icelandic Conv

“FATE MUST FIND SOMEONE TO SPEAK THROUGH”: CHRISTIANITY, RAGNARÖK, AND THE LOSS OF ICELANDIC INDEPENDENCE IN THE EYES OF THE ICELANDERS AS ILLUSTRATED BY GÍSLA SAGA SÚRSSONAR Item Type Thesis Authors Mjolsnes, Grete E. Download date 01/10/2021 15:39:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/81 1 “FATE MUST FIND SOMEONE TO SPEAK THROUGH”: CHRISTIANITY, RAGNARÖK, AND THE LOSS OF ICELANDIC INDEPENDENCE IN THE EYES OF THE ICELANDERS AS ILLUSTRATED BY GÍSLA SAGA SÚRSSONAR A THESIS Presented to the Faculty Of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Grete E. Mjolsnes, B. A. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2008 2 Abstract Iceland surrendered political control to the Norwegian monarchy in 1262, but immediately resented their choice. The sagas about reliance on the Norwegians, clearly illustrating that the Icelanders knew where this path was leading them. Gísla Saga is a particularly interesting text to examine in light of the contemporaneous political climate, as it takes place in the years leading up to the conversion but was written between the conversion and the submission to Norwegian rule. Though Gísla does not explicitly comment on either the conversion or the increase in Norwegian influence, close examination illuminates ambiguity in the portrayal of Christian and pagan characters and a general sense of terminal foreboding. This subtle commentary becomes clearer when one reads Gísla Saga in light of the story of Ragnarök, the death of the gods and the end of the Norse world. Characters and images in Gísla Saga may be compared with the events of Ragnarök, the apocalyptic battle between the Æsir and the giants, illustrating how the Christian conversion and Norwegian submission brought about the end of Iceland’s golden age by destroying the last home of the Norse gods. -

Trevor Morris

TREVOR MORRIS COMPOSER Trevor Morris is one of the most prolific and versatile composers in Hollywood. He has scored music for numerous feature films and won two EMMY awards for outstanding composition for his work in Television. Internationally renowned for his music on The Tudors, The Borgias, Vikings and the hit NBC television series Taken, Trevor is a stylistically and musically inventive soundtrack creator. Trevor’s unique musical voice can be heard on his recent film scores which include The Delicacy, Hunter Killer, Asura, Olympus Has Fallen, London Has Fallen, and Immortals. And further Television compositions including Another Life, Condor, Castlevania, The Pillars oF the Earth for Tony and Ridley Scott, Emerald City and Iron Fist for Marvel Television. Trevor has also worked as a co-producer/ conductor/ orchestrator on films including Black Hawk Down, The Last Samurai, The Ring Two, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Batman Begins and collaborated with Tony and Ridley Scott, Neil Jordan, Luc Besson, Jerry Bruckheimer, Antoine Fuqua, Tarsem Singh Dandwar, as well as composers James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer. Trevor is also a Concert Conductor, conducting his music in live concert performances around the globe, including Film Music Festivals in Cordoba Spain, Tenerife Spain, Los Angeles, and Krakow Poland where he conducted a 100-piece orchestra and choir for over 12,000 fans. Trevor has been nominated 5 times for the prestigious EMMY awards, and won twice. As well as being nominated at the World Soundtrack Awards in Ghent for the ‘Discovery of the Year ‘composer award for the film Immortals. Trevor is a British/Canadian dual citizen, based in Los Angeles. -

A Viking Encounter’ the Vikings Came from the Scandinavian Countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark

Map of Viking Routes Year Five – ‘A Viking Encounter’ The Vikings came from the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden and Denmark. The time between 787AD and 1050AD is known as the time of the Vikings. Initially, they settled in northern Scotland and eastern England, also establishing the city of Dublin in Ireland. Around 1000AD, some Vikings settled in North America, but did not stay long. They also travelled to southern Spain and Russia, and traded as far away as Turkey. ‘A Viking Encounter’ Useful Websites https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/ztyr9j6 https://www.jorvikvikingcentre.co.uk/ https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/discover/history/general-history/10- facts-about-the-vikings/ https://www.funkidslive.com/learn/top-10-facts-about-vikings/# https://www.dkfindout.com/uk/history/vikings/ Were the Vikings victorious or simply vicious? –The 840 AD – Viking – Danish Vikings 878-886 AD– King Alfred divides 900-911 AD – The Vikings 787-789 AD 866 AD Vikings begin their settlers establish the city of establish a kingdom in England under the Danelaw Act, raid the Mediterranean, and attacks on Britain. Dublin in Ireland. York, England. granting Vikings north & east England. found Normandy in France. Ragnar Lodbrok (740/780-840 AD) Ivar the Boneless (794-873 AD) Erik the Red (950AD-1003AD) Ragnar Ladbrok is a legendary Danish and Swedish Viking leader, who is Ivar the Boneless was a notoriously Erik Thorvaldsson, known as Erik the Red, was a largely known from Viking Age Old ferocious Viking leader and commander Norse explorer, famed for having founded the Norse poetry and literature (there is who invaded what is now England. -

Quick Questions

The Magic Hammer Quick Questions When the Vikings first came to Britain they were Pagans, 1. Who did the Vikings worship originally? worshipping Norse gods. The king of the gods was Odin, who had a son, Thor, the God of Thunder. Thor’s magic hammer, which could kill an army or bring peace to the world, was missing; the unintelligent frost giant, Thrym, 2. Which two words mean the same as ‘get back’? had stolen it! Loki, the giant and god of Mischief, was sent to find Thrym to retrieve the hammer. However, Thrym laughed and gave Loki an ultimatum: “I will return the hammer if I am given Freya, the Goddess of Love, to be my wife.” Loki had a mischievous plan - rather than send poor Freya, Thor put on a 3. Why do you think that Thrym stole the magic dress and went to reclaim his hammer. hammer? 4. Do you think that Thor managed to recover his hammer? Why do you think this? visit twinkl.com visit twinkl.com The Magic Hammer Answers When the Vikings first came to Britain they were Pagans, 1. Who did the Vikings worship originally? worshipping Norse gods. The king of the gods was Odin, who Accept: Norse gods. had a son, Thor, the God of Thunder. Thor’s magic hammer, which could kill an army or bring peace 2. Which two words mean the same as ‘get back’? to the world, was missing; the unintelligent frost giant, Thrym, Accept: ‘retrieve’ and ‘reclaim’. had stolen it! Loki, the giant and god of Mischief, was sent to find Thrym to retrieve the hammer. -

S Hit Drama Series Vikings Marks Its Final Season with a Powerful Two-Hour Premiere on Wednesday, December 4 at 9 P.M

HISTORY®’S HIT DRAMA SERIES VIKINGS MARKS ITS FINAL SEASON WITH A POWERFUL TWO-HOUR PREMIERE ON WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 4 AT 9 P.M. ET/PT Twenty–Episode Season to Air in Two Parts Special Vikings: Worlds at War – with ET Canada Premieres Sunday, December 1 at 8:30 p.m. ET/PT on HISTORY Watch Season 6 Trailer Here For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.corusent.com To share this socially: bit.ly/2AFuFvr For Immediate Release TORONTO, October 7, 2019 – HISTORY’s hit drama series Vikings returns for its sixth and final season with a highly anticipated and powerful two-hour premiere kicking off Wednesday, December 4 at 9 p.m. ET/PT. For the past five seasons the Vikings have explored and conquered the known world, from early raids in England and the fierce battles of the Great Heathen Army to the heart-stopping death of Ragnar (Travis Fimmel), now the epic saga sails to monumental lengths throughout 20 compelling, definitive episodes. The 20-episode sixth season will air in two parts, beginning with a two-hour premiere on Wednesday, December 4 at 9 p.m. ET/PT, followed by eight episodes airing every Wednesday at 10 p.m. ET/PT on HISTORY. The remaining ten episodes of Season 6 are slated to air in 2020. Additionally, series regular Katheryn Winnick is set to helm one episode in Season 6, marking her directorial debut. Accompanying the series return is an all-new special, Vikings: Worlds at War – with ET Canada, premiering Sunday, December 1 at 8:30 p.m. -

Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia Michael David Lawson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2019 Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia Michael David Lawson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Disability Studies Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Folklore Commons, History of Religion Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Scandinavian Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Michael David, "Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3538. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3538 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia ————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University ————— In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Viking Hersir Free

FREE VIKING HERSIR PDF Mark Harrison,Gerry Embleton | 64 pages | 01 Nov 1993 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781855323186 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom hersir - Wiktionary Goodreads helps Viking Hersir keep track of books you Viking Hersir to Viking Hersir. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. When Norwegian Vikings first raided the European coast in the 8th century AD, their leaders were from the middle ranks of warriors known as hersirs. At this time the hersir was typically an independent landowner or local chieftain with equipment superior to that of his followers. By the end of the Viking Hersir century, the independence of the hersir was gone, and he was Viking Hersir a regi When Norwegian Vikings first raided the European coast in the 8th century AD, their leaders were from the middle ranks of warriors known as hersirs. By the end of the 10th century, the independence of the hersir was gone, and he was now a regional servant of the Norwegian king. This book investigates these brutal, mobile warriors, and examines their tactics and psychology in war, dispelling the idea of the Viking raider as simply a killing machine. Get A Copy. Paperback64 pages. More Details Original Title. Osprey Viking Hersir 3. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers Viking Hersir about Viking Hersir — AD Viking Hersir, please sign up.