The Western Spread of Permic Hydronyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

VÁCLAV BLAŽEK Masaryk University Fields of research: Indo-European studies, especially Slavic, Baltic, Celtic, Anatolian, Tocharian, Indo-Iranian languages; Fenno-Ugric; Afro-Asiatic; etymology; genetic classification; mathematic models in historical linguistics. AN ATTEMPT AT AN ETYMOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF PTOLEMY´S HYDRONYMS OF EASTERN BALTICUM Bandymas etimologiškai analizuoti Ptolemajo užfiksuotus rytinio Baltijos regiono hidronimus ANNOTATION The contribution analyzes four hydronyms from Eastern Balticum, recorded by Ptole- my in the mid-2nd cent. CE in context of witness of other ancient geographers. Their re- vised etymological analyses lead to the conclusion that at least three of them are of Ger- manic origin, but probably calques on their probable Baltic counterparts. KEYWORDS: Geography, hydronym, etymology, calque, Germanic, Baltic, Balto-Fennic. ANOTACIJA Šiame darbe analizuojami keturi Ptolemajo II a. po Kr. viduryje užrašyti rytinio Bal- tijos regiono hidronimai, paliudyti ir kitų senovės geografų. Šių hidronimų etimologinė analizė parodė, kad bent trys iš jų yra germaniškos kilmės, tačiau, tikėtina, baltiškų atitik- menų kalkės. ESMINIAI ŽODŽIAI: geografija, hidronimas, etimologija, kalkė, germanų, baltų, baltų ir finų kilmė. Straipsniai / Articles 25 VÁCLAV BLAŽEK The four river-names located by Ptolemy to the east of the eastuary of the Vistula river, Χρόνος, Ῥούβων, Τουρούντος, Χε(ρ)σίνος, have usually been mechanically identified with the biggest rivers of Eastern Balticum according to the sequence of Ptolemy’s coordinates: Χρόνος ~ Prussian Pregora / German Pregel / Russian Prególja / Polish Pre- goła / Lithuanian Preglius; 123 km (Mannert 1820: 257; Tomaschek, RE III/2, 1899, c. 2841). Ῥούβων ~ Lithuanian Nemunas̃ / Polish Niemen / Belorussian Nëman / Ger- man Memel; 937 km (Mannert 1820: 258; Rappaport, RE 48, 1914, c. -

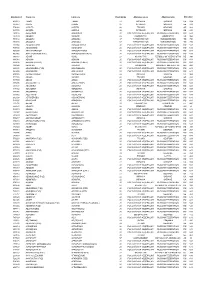

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY of the BIOSPHERE (Prirodnaya Radioaktivnost' Iosfery)

XA04N2887 INIS-XA-N--259 L.A. Pertsov TRANSLATED FROM RUSSIAN Published for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. by the Israel Program for Scientific Translations L. A. PERTSOV THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY OF THE BIOSPHERE (Prirodnaya Radioaktivnost' iosfery) Atomizdat NMoskva 1964 Translated from Russian Israel Program for Scientific Translations Jerusalem 1967 18 02 AEC-tr- 6714 Published Pursuant to an Agreement with THE U. S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION and THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, WASHINGTON, D. C. Copyright (D 1967 Israel Program for scientific Translations Ltd. IPST Cat. No. 1802 Translated and Edited by IPST Staff Printed in Jerusalem by S. Monison Available from the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information Springfield, Va. 22151 VI/ Table of Contents Introduction .1..................... Bibliography ...................................... 5 Chapter 1. GENESIS OF THE NATURAL RADIOACTIVITY OF THE BIOSPHERE ......................... 6 § Some historical problems...................... 6 § 2. Formation of natural radioactive isotopes of the earth ..... 7 §3. Radioactive isotope creation by cosmic radiation. ....... 11 §4. Distribution of radioactive isotopes in the earth ........ 12 § 5. The spread of radioactive isotopes over the earth's surface. ................................. 16 § 6. The cycle of natural radioactive isotopes in the biosphere. ................................ 18 Bibliography ................ .................. 22 Chapter 2. PHYSICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF NATURAL RADIOACTIVE ISOTOPES. ........... 24 § 1. The contribution of individual radioactive isotopes to the total radioactivity of the biosphere. ............... 24 § 2. Properties of radioactive isotopes not belonging to radio- active families . ............ I............ 27 § 3. Properties of radioactive isotopes of the radioactive families. ................................ 38 § 4. Properties of radioactive isotopes of rare-earth elements . -

COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 2005 Amending for The

L 340/70EN Official Journal of the European Union 23.12.2005 COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 2005 amending for the second time Decision 2005/693/EC concerning certain protection measures in relation to avian influenza in Russia (notified under document number C(2005) 5563) (Text with EEA relevance) (2005/933/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, cessed parts of feathers from those regions of Russia listed in Annex I to that Decision. Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, (3) Outbreaks of avian influenza continue to occur in certain parts of Russia and it is therefore necessary to prolong the measures provided for in Decision 2005/693/EC. The Decision can however be reviewed before this date depending on information supplied by the competent Having regard to Council Directive 91/496/EEC of 15 July 1991 veterinary authorities of Russia. laying down the principles governing the organisation of veterinary checks on animals entering the Community from third countries and amending Directives 89/662/EEC, 90/425/EEC and 90/675/EEC (1), and in particular Article 18(7) thereof, (4) The outbreaks in the European part of Russia have all occurred in the central area and no outbreaks have occurred in the northern regions. It is therefore no longer necessary to continue the suspension of imports of unprocessed feathers and parts of feathers from the Having regard to Council Directive 97/78/EC of 18 December latter. 1997 laying down the principles governing the organisation of veterinary checks on products entering the Community from third countries (2), and in particular Article 22 (6) thereof, (5) Decision 2005/693/EC should therefore be amended accordingly. -

Annual Report of the Tatneft Company

LOOKING INTO THE FUTURE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TATNEFT COMPANY ABOUT OPERATIONS CORPORATE FINANCIAL SOCIAL INDUSTRIAL SAFETY & PJSC TATNEFT, ANNUAL REPORT 2015 THE COMPANY MANAGEMENT RESULTS RESPONSIBILITY ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY CONTENTS ABOUT THE COMPANY 01 Joint Address to Shareholders, Investors and Partners .......................................................................................................... 02 The Company’s Mission ....................................................................................................................................................... 04 Equity Holding Structure of PJSC TATNEFT ........................................................................................................................... 06 Development and Continuity of the Company’s Strategic Initiatives.......................................................................................... 09 Business Model ................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Finanical Position and Strengthening the Assets Structure ...................................................................................................... 12 Major Industrial Factors Affecting the Company’s Activity in 2015 ............................................................................................ 18 Model of Sustainable Development of the Company .............................................................................................................. -

Exonyms – Standards Or from the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4

NO. 50 JUNE 2016 In this issue Preface Message from the Chairperson 3 Exonyms – standards or From the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4 Special Feature – Exonyms – standards standardization? or standardization? What are the benefits of discerning 5-6 between endonym and exonym and what does this divide mean Use of Exonyms in National 6-7 Exonyms/Endonyms Standardization of Geographical Names in Ukraine Dealing with Exonyms in Croatia 8-9 History of Exonyms in Madagascar 9-11 Are there endonyms, exonyms or both? 12-15 The need for standardization Exonyms, Standards and 15-18 Standardization: New Directions Practice of Exonyms use in Egypt 19-24 Dealing with Exonyms in Slovenia 25-29 Exonyms Used for Country Names in the 29 Repubic of Korea Botswana – Exonyms – standards or 30 standardization? From the Divisions East Central and South-East Europe 32 Division Portuguese-speaking Division 33 From the Working Groups WG on Exonyms 31 WG on Evaluation and Implementation 34 From the Countries Burkina Faso 34-37 Brazil 38 Canada 38-42 Republic of Korea 42 Indonesia 43 Islamic Republic of Iran 44 Saudi Arabia 45-46 Sri Lanka 46-48 State of Palestine 48-50 Training and Eucation International Consortium of Universities 51 for Training in Geographical Names established Upcoming Meetings 52 UNGEGN Information Bulletin No. 50 June 2106 Page 1 UNGEGN Information Bulletin The Information Bulletin of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly UNGEGN Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group of Experts. The Secretariat is served by the Statistics Division (UNSD), Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Secretariat of the United Nations. -

My Birthplace

My birthplace Ягодарова Ангелина Николаевна My birthplace My birthplace Mari El The flag • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno- Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva, Komis (Zyrians) ,Karelians ,Komi-Permians ,Maris (Cheremises), Mordvinians (Erzas and Mokshas), Udmurts (Votiaks) ,Vepsians ,Mansis (Voguls) ,Saamis (Lapps), Khanti. Mari people speak a language of the Finno-Ugric family and live mainly in Mari El, Russia, in the middle Volga River valley. • http://aboutmari.com/wiki/Этнографические_группы • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9NpQZZGuPI&feature=r elated • The rich history of Mari land has united people of different nationalities and religions. At this moment more than 50 ethnicities are represented in Mari El republic, including, except the most numerous Russians and Мari,Tatarians,Chuvashes, Udmurts, Mordva Ukranians and many others. Compare numbers • Finnish : Mari • 1-yksi ikte • 2-kaksi koktit • 3- kolme kumit • 4 -neljä nilit • 5 -viisi vizit • 6 -kuusi kudit • 7-seitsemän shimit • 8- kahdeksan kandashe • the Mari language and culture are taught. Lake Sea Eye The colour of the water is emerald due to the water plants • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno-Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva. • We have our language. We speak it, study at school, sing our tuneful songs and listen to them on the radio . Mari people are very poetic. Tourism Mari El is one of the more ecologically pure areas of the European part of Russia with numerous lakes, rivers, and forests. As a result, it is a popular destination for tourists looking to enjoy nature. -

Complex of Stone Tools of the Chalcolithic Igim Settlement 1 2 *3 Ekaterina N

DOI 10.29042/2018-2284-2288 Helix Vol. 8(1): 2284 – 2288 Complex of Stone Tools of the Chalcolithic Igim Settlement 1 2 *3 Ekaterina N. Golubeva , Madina S. Galimova , Leonard F. Nedashkovsky *1, 3 Kazan Federal University 2Institute of Archaeology named after A.Kh. Khalikov of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan *3E-mail: [email protected], Contact: 89050229782 Received: 21st October 2017 Accepted: 16th November 2017, Published: 31st December 2017 expand the understanding of the everyday life and the Abstract activities of prehistoric people, but also, perhaps, to The article presents the results of a typological and a functional study of stone objects collection part (408 differentiate the complexes of stone inventory for items) originating from trench 2 on a multi-layered different periods of time. Igim site situated in the Lower Kama reservoir zone at A striking example of such a mixed monument is the the confluence of the Ik and Kama rivers (Russian multi-layered settlement Igim, which is located on the Federation, Republic of Tatarstan). The site was high remnant of the terrace, at the confluence of the inhabited for three periods - during the Neolithic, the rivers Ik and Kama (now the Lower Kama reservoir). Eneolithic and the Late Bronze Age. In the course of This large remnant restricts from the west a large lake- research conducted by P.N. Starostin and R.S. marshy massif, called Kulegash, located between the Gabyashev, stone artifacts were discovered, probably mouths of the largest influents of the Kama River - Ik related to the Eneolithic era. -

1 GOLDEN RING TOUR – PART 3 Golden Gate, Vladimir

GOLDEN RING TOUR – PART 3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Gate,_Vladimir Golden Gate, Vladimir The Golden Gate of Vladimir (Russian: Zolotye Vorota, Золотые ворота), constructed between 1158 and 1164, is the only (albeit partially) preserved ancient Russian city gate. A museum inside focuses on the history of the Mongol invasion of Russia in the 13th century. 1 Inside the museum. 2 Side view of the Golden Gate of Vladimir. The Trinity Church Vladimir II Monomakh Monument, founder http://ermakvagus.com/Europe/Russia/Vladimir/trinity_church_vladimir.html https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_II_Monomakh 3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dormition_Cathedral,_Vladimir The Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir (sometimes translated Assumption Cathedral) (Russian: Собор Успения Пресвятой Богородицы, Sobor Uspeniya Presvyatoy Bogoroditsy) was a mother church of Medieval Russia in the 13th and 14th centuries. It is part of a World Heritage Site, the White Monuments of Vladimir and Suzdal. https://rusmania.com/central/vladimir-region/vladimir/sights/around-sobornaya- ploschad/andrey-rublev-monument Andrey Rublev monument 4 5 Cathedral of Saint Demetrius in Vladimir https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathedral_of_Saint_Demetrius 6 7 Building of the Gubernia’s Administration museum (constructed in 1785-1790). Since 1990s it is museum. January 28, 2010 in Vladimir, Russia. Interior of old nobility Palace (XIX century) 8 Private street vendors 9 Water tower https://www.advantour.com/russia/vladimir/water-tower.htm 10 Savior Transfiguration church https://www.tourism33.ru/en/guide/places/vladimir/spasskii-i-nikolskiy-hramy/ Cities of the Golden Ring 11 Nikolo-Kremlevskaya (St. Nicholas the Kremlin) Church, 18th century. https://www.tourism33.ru/en/guide/places/vladimir/nikolo-kremlevskaya-tcerkov/ Prince Alexander Nevsky (Невский) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Nevsky 12 Just outside of Suzdal is the village of Kideksha which is famous for its Ss Boris and Gleb Church which is one of the oldest white stone churches in Russia, dating from 1152. -

Kiyameti Beklerken: Hiristiyanlik'ta

Hitit Üniversitesi Đlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 2008/2, c. 7, sayı: 14, ss. 5-36. KIYAMETİ BEKLERKEN: HIRİSTİYANLIK’TA KIYAMET BEKLENTİLERİ VE RUS ORTODOKS KİLİSESİNDEKİ YANSIMALARI Cengiz BATUK * Özet Kıyameti Beklerken: Hıristiyanlık’ta Kıyamet Beklentileri ve Rus Ortodoks Kilise- sindeki Yansımaları Bu çalışmanın amacı Hıristiyan tarihindeki kıyamet beklentilerini araştırmaktır. Hıristiyanlıktaki kıyamet beklentileri genellikle binyılcı ve Mesihçi hareketler şeklinde ortaya çıktığı için çalışmanın ilk bölümünde bu hareketlerden bir kısmı hakkında değerlendirmeler yapılmıştır. Đkinci bölümde Rus Ortodoks Kilisesi tarihinde apokaliptik hareketler hakkında incelemeler yapılmıştır. Bu hareketlerden bazıları Pyotr Kuznetsov’un kıyamet kültü, castrati ve neo-castrati tarikatları, Sergei Torop’un Son Ahit Kilisesi ve Mesihçiler/Flagellant hareketleridir. Anahtar kelimeler : Kıyamet Kültü, Binyılcılık, Apokaliptisizm, Mesihçilik, Ortodoks Kilisesi, Pyotr Kuznetsov, Sergei Torop, Skoptsy -Castrati. Abstract To Await Doomsday: Expectations of Doomsday in the Christianity and Reflections in the Russian Orthodox Church The Purpose of this article is to examine expectations of doomsday in the history of Christianity. Since expectations of doomsday in Christianity appears in form of millenarianist and messianic sects, analyzes have been done some of this sects in first chapter of the study. In second chapter, investigations have been done about apocalyptic movements in history of Russian Orthodox Church. Some of these movements are Pyotr Kuznetsov’s doomsday cult, sects of castrati and neo- castrati, Sergei Torop’s Church of the Last Testament and sect of Khristovshchina/Flagellant. Key words : Doomsday Cult, Millenarianism, Apocalypticism, Ortodox Church, Messianism, Pyotr Kuznetsov, Sergei Torop, Skoptsy–Castrati. * Yrd. Doç. Dr., Rize Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dinler Tarihi Anabilim Dalı. Hitit Üniversitesi Đlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 2008/2, c. 7, sayı: 14 6 | Yrd. -

DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized

SOCIAL PROTECTION & JOBS DISCUSSION PAPER Public Disclosure Authorized No. 1931 | MAY 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Can Local Participatory Programs Enhance Public Confidence: Insights from the Local Initiatives Support Program in Russia Public Disclosure Authorized Ivan Shulga, Lev Shilov, Anna Sukhova, and Peter Pojarski Public Disclosure Authorized © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: +1 (202) 473 1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, -

Материалы Совещания Рабочей Группы INQUA Peribaltic

САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ Материалы совещания рабочей группы INQUA Peribaltic Из сборника материалов совместной международной конференции «ГЕОМОРФОЛОГИЯ И ПАЛЕОГЕОГРАФИЯ ПОЛЯРНЫХ РЕГИОНОВ», симпозиума «Леопольдина» и совещания рабочей группы INQUA Peribaltic, Санкт-Петербург, СПбГУ, 9 – 17 сентября 2012 года Санкт-Петербург, 2012 SAINT-PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY Proceedings of the INQUA Peribaltic Working Group Workshop From the book of proceeding of the Joint International Conference “GEOMORPHOLOGY AND PALАEOGEOGRAPHY OF POLAR REGIONS”, Leopoldina Symposium and INQUA Peribaltic Working Group Workshop, Saint-Petersburg, SPbSU, 9-17 September, 2012 Saint-Petersburg, 2012 УДК 551.4 Ответственные редакторы: А.И. Жиров, В.Ю. Кузнецов, Д.А. Субетто, Й. Тиде Техническое редактирование и компьютерная верстка: А.А. Старикова, В.В. Ситало Обложка: К.А. Смыкова «ГЕОМОРФОЛОГИЯ И ПАЛЕОГЕОГРАФИЯ ПОЛЯРНЫХ РЕГИОНОВ»: Материалы совместной международной конференции «ГЕОМОРФОЛОГИЯ И ПАЛЕОГЕОГРАФИЯ ПОЛЯРНЫХ РЕГИОНОВ», симпозиума «Леопольдина» и совещания рабочей группы INQUA Peribaltic. Санкт-Петербург, СПбГУ, 9 – 17 сентября 2012 года / Отв. ред. А.И. Жиров, В.Ю. Кузнецов, Д.А. Субетто, Й. Тиде. – СПб., 2012. – 475 с. ISBN 978-5-4391-0029-3 Сборник содержит материалы совместной международной конференции "Геоморфологические и палеогеографические исследования полярных регионов", симпозиума «Леопольдина» и совещания рабочей группы INQUA Peribaltic. Обсуждается целый ряд актуальных вопросов, связанных с изучением проблем теоретической