Articles More Effectively Than Exotic Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

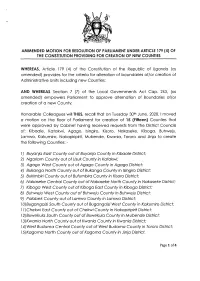

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

State of the Environment Report for Uganda 2006/2007

STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR UGANDA 2006/2007 Copy right @ 2006/07 National Environment Management Authority All rights reserved. National Environment Management Authority P.O Box 22255 Kampala, Uganda http://www.nemaug.org [email protected] Publication: This publication is available both in hard copy and on the website of the National Environment Management Authority, www.nemaug.org. A charge will be levied according to the pricing policy in the authority. Suggested citation: National Environment Management Authority, 2006/07, State of Environment Report for Uganda, NEMA, Kampala. 332pp. This publication is available at the following libraries: National Environment Management Authority, Library. National Environment Management Authority Store. District Environment Offices. District Environment Resource Centers Public libraries. Makerere University library Kyambogo University library. Editor in chief: Mrs Kitutu Kimono Mary Goretti Copy editing: Dr Kiguli Susan and Mr Merit Kabugo Authors: Ema Consult Dr. Moyini Yakobo (Team leader). Review team: Dr. Aryamanya Mugisha Henry National Environment Management Authority. Mr. Telly Eugene Muramira National Environment Management Authority. Dr. Festus Bagoora National Environment Management Authority. Mrs. Mary Goretti Kitutu Kimono National Environment Management Authority. Mr. George Lubega National Environment management Authority. Mr. Francis Ogwal National Environment Management Authority. Mr. Ronald Kaggwa National Environment Management Authority. Ms. Margaret Lwanga National Environment Management Authority. Mr. Firipo Mpabulungi National Environment Management Authority. Ms. Elizabeth Mutayanjulwa National Environment Management Authority. Ms. Margaret Aanyu National Environment Management Authority. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) is again honored to present another edition of the State of the Environment Report for Uganda. This is the seventh report since the first one was published in 1994. -

Semi-Annual Partner Management Report

Semi-annual Partner Management Report Contact person: Opwonya Tom Partner Address: Plot 11, ASDI Building, Republic Street, Akere Division, Apac Municipality Telephone: Mobile 0772647107, Office: 0790915362 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Website: www.taacc.org.ug ©The Apac Anti-Corruption Coalition December 2016 Semi-annual Partner Management Report Page ii 1. Basic Project Information Profile Name of project Strengthening citizens’ capacity to monitor, report and engage duty bearers for improved service delivery. Project goal Project Goal: Informed and empowered citizens engaging and holding duty bearers accountable for effective service delivery by 2017. Project Objectives Objective 1. Empower citizens to monitor & report misuse of public resources & poor service delivery in target 3 districts. Objective 2: Strengthen the capacity of duty bearers to constructively engage and provide effective service delivery to the citizens. Objective 3. Strengthen the institutional capacity of TAACC to deliver services effectively to the target beneficiaries. Location of the project Northern Uganda Geographical coverage Apac, Kole and Oyam districts Contract start date 1st July 2016 Contract end date 31st December 2017 Total project lifetime Budget Ugx. 736,327,763/= Planned budget for the reporting period Ugx. 89,908,884/= Actual expenditure for the reporting period Ugx. 121,483,832/= Contact person Opwonya Tom 2. Executive Summary The 18 months project goal is an informed and empowered citizens engaging and holding duty bearers accountable for effective service delivery by 2017. The emphasis of the project is to scale up community capacity building, facilitate and mentor community structures and the target community in the 3 target districts to monitor, report and engage duty bearers to reduce inefficiency, fight corruption and ensure equitable quality service delivery contributing to sustainable development. -

ASSESSMENT REPORT APAC.Pdf

Local Government Performance Assessment Apac District (Vote Code: 502) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements 67% Crosscutting Performance Measures 52% Educational Performance Measures 47% Health Performance Measures 77% Water Performance Measures 85% 502 Apac District Accontability Requirements 2018 Definition of Summary of requirements Compliance justification Compliant? compliance Annual performance contract Yes LG has submitted an annual • From MoFPED’s The District LG submitted the performance contract of the inventory/schedule of approved Budget Estimates that forthcoming year by June 30 LG submissions of included a Procurement Plan for the on the basis of the PFMAA performance contracts, FY 2018/19 on 22nd July, 2018. This and LG Budget guidelines for check dates of date of submission was in line with the coming financial year. submission and the last official date of 1st August set issuance of receipts by the MoFPED. The District was and: therefore complaint. o If LG submitted Note: The PFMAA LG Budget before or by due date, guidelines require the submission to then state ‘compliant’ be by 30th June. However, this date was revised to 1st August 2018 as o If LG had not amended by the LGPA Manual June, submitted or submitted 2018. later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available Yes LG has submitted a Budget • From MoFPED’s The District LG submitted the that includes a Procurement inventory of LG budget approved Budget Estimates that Plan for the forthcoming FY submissions, check included a Procurement Plan for the by 30th June (LG PPDA whether: FY 2018/19 on 22nd July, 2018. -

Uganda Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers (Ugift) Programme

UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME Front View of the completed Upgraded Pandwong HC Front View of the Science Laboratory under Construction III, Kitgum Municipal Council at Kimenyedde Seed Secondary School, Mukono District The 2nd Joint Monitoring of Seed Secondary Schools and Upgrade of Health Centre IIs to III conducted from 27th July – 7th August, 2020 Final Report October 2020 MOFPED MofpedU #DoingMore 1 UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME Front View of the completed Upgraded Pandwong HC III, Kitgum Front View of the Science Laboratory under Construction at Municipal Council Kimenyedde Seed Secondary School, Mukono District The 2nd Joint Monitoring of Seed Secondary Schools and Upgrade of Health Centre IIs to III conducted from 27th July – 7th August, 2020 Final Report October 2020 UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME Table of Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables v Acronyms vi Foreword 1 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2.0 THE SECOND(2ND) JOINT MONITORING EXERCISE 3 2.1 Background and objectives 3 2.2 The Joint Monitoring approach 4 2.2.1 Team Composition 4 2.2.2 Objectives of the Joint Monitoring 4 2.2.3 The Second Joint Monitoring Programme 4 2.2.4 Projects Monitored 4 2.2.5 Monitoring, Reporting and Data Analysis tools 5 FINDINGS FROM THE 2ND JOINT MONITORING EXERCISE 6 3.0 SEED SECONDARY SCHOOLS 6 3.1 Contract Management 6 3.1.1 Validity of contracts for on-going Seed Secondary -

Message from DGF Welcome to Yet Another Issue of the Special Newsletter on Our Implementing Partners’ Response to Governance Issues Related to the COVID-19 Outbreak

Message from DGF Welcome to yet another issue of the special newsletter on our implementing partners’ response to governance issues related to the COVID-19 outbreak. In this issue, we continue to share with you the various interventions and innovations our partners are pursuing to strengthen governance in Uganda, amidst the outbreak of corona virus. SPECIAL NEWSLETTER ON DGF IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS’ In responding to the challenges caused RESPONSE TO COVID-19, ISSUE 3, JULY 2020 by COVID-19 related restriction on their programme operations, many of our partners have adopted new Women Organisations Caution the Electoral Commission on approaches to their programming in order to adhere to the Ministry of Using Media as the Only Campaign Platform for 2021 Elections Health guidelines on COVID-19. forthcoming campaigns because they lead to huge congregations and physical contacts For example, some of our partners have opted for online technologies known for spreading the COVID-19. and various media channels to engage with their beneficiaries on issues At the press conference, UWONET such as prevention of COVID-19; noted that whereas they appreciate the accountability for COVID-19 resources; gender-based violence; leadership creativity of the EC in organising a scientific and governance; access to service election given the unprecedented times delivery; and citizens’ rights, roles and Representatives of women organisatons address of COVID-19, they are concerned that responsibilities, among others. journalists at a Press Conference in Kampala. ‘digitalising elections’ might combine with (Source: UWONET) pre-existing inequalities to undermine We appreciate our partners for the commendable work they are doing omen organisations through their women, youth and rural populations from even during these uncertain times network, the Uganda Women’s participating in the forthcoming election, to ensure continuation of their WNetwork (UWONET), held a press both as voters and candidates. -

Kwania District

Local Government Performance Assessment Kwania District (Vote Code: 626) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements % Crosscutting Performance Measures 71% Educational Performance Measures 54% Health Performance Measures 56% Water & Environment Performance Measures 39% 626 Accountability Requirements 2019 Kwania District No. Summary of requirements Definition of compliance Compliance justification Compliant? Annual performance contract 1 Yes LG has submitted an annual performance • From MoFPED’s Kwania DLG submitted the contract of the forthcoming year by June inventory/schedule of LG Annual Performance Contract on 30 on the basis of the PFMAA and LG submissions of 23rd July, 2019. This was within Budget guidelines for the coming performance contracts, the MoFPED adjusted financial year. check dates of submission submission deadline of 31st and issuance of receipts August, 2019. and: o If LG submitted before or by due date, then state ‘compliant’ o If LG had not submitted or submitted later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available 2 Yes LG has submitted a Budget that includes • From MoFPED’s Kwania DLG submitted the a Procurement Plan for the forthcoming inventory of LG budget Budget that included the FY by 30th June (LG PPDA Regulations, submissions, check Procurement Plan for the FY 2006). whether: 2019/2020 on 23rd July, 2019. This was within the MoFPED o The LG budget is adjusted submission deadline of accompanied by a 31st August, 2019. Procurement Plan or not. -

PEPFAR Uganda Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019

PEPFAR Uganda Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement .................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context ....................................................................... 7 2.1 Summary Statistics, Disease Burden and Country Profile ................................................. 7 2.2 Investment Profile ............................................................................................................................. 19 2.3 National Sustainability Profile Update .............................................................................................. 24 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR Investments Geographically to Disease Burden ............................................ 28 2.5 Stakeholder Engagement .................................................................................................................. 29 3.0 Geographic and Population Prioritization ...................................................................... 32 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-Up Locations and Populations .. 33 4.1 Finding the missing, getting them on treatment, and retaining them ensuring viral suppression .. 34 4.2 Prevention, specifically detailing programs for priority programming: ........................................... 52 4.2.a. OVC and Child-Focused COP19 Interventions .......................................................................... -

Developed Special Postcodes

REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF INFORMATION & COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AND NATIONAL GUIDANCE DEVELOPED SPECIAL POSTCODES DECEMBER 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS KAMPALA 100 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 EASTERN UGANDA 200 ........................................................................................................................... 5 CENTRAL UGANDA 300 ........................................................................................................................... 8 WESTERN UGANDA 400 ........................................................................................................................ 10 MID WESTERN 500 ................................................................................................................................ 11 WESTNILE 600 ....................................................................................................................................... 13 NORTHERN UGANDA 700 ..................................................................................................................... 14 NORTH EASTERN 800 ............................................................................................................................ 15 KAMPALA 100 No. AREA POSTCODE 1. State House 10000 2. Parliament Uganda 10001 3. Office of the President 10002 4. Office of the Prime Minister 10003 5. High Court 10004 6. Kampala Capital City Authority 10005 7. Central Division 10006 -

Project Evaluation Report Citizen Action Platform (CAP)

ANTI CORRUPTION COALITION UGANDA Project Evaluation Report Citizen Action Platform (CAP) Submitted on 18th January, 2016 By Harriet Namisi, Tel: +256 392944674/772-672259, [email protected] /[email protected], Plot 49/51, Bukoto Street – Kamwokya, P.O BOX 9460, Kampala This report highlights an evaluation of the project expected results its contribution to the expected development outcomes. 1 Acknowledgments This evaluation was as a result of support from the Apac Anti Corruption Coalition (TAACC), Apac Local Government, and citizens that participated in the implementation and evaluation process of this project. This work attracted a considerable amount of hard work and dedication from government, organizations, and individuals. We therefore extend our appreciation to all of you. We would like to thank the Partnership for Transparency Fund (PTF) for the financial support towards the project and for the technical backstopping provided during the implementation phase. We are also grateful to Apac District Local Government, The Apac Anti-corruption Coalition and Transparency International in Uganda for accepting to partner with us during the implementation of this project without which, it would have been impossible to get this far. Our sincere thanks go out to the technical team which includes Lilian Kaweesa, Evaline Ayugi and Roy Mukasa for their technical expertise, input and tireless support during the implementation of this project. Finally, our appreciation goes to Harriet Namisi for carrying out this evaluation exercise and putting -

Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) the REPUBLIC of UGANDA OFFICE of the PRIME MINISTER EUROPEAN UNION

Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER EUROPEAN UNION Building resilience to enhance food and nutrition security, income and health in Northern Uganda (BRENU) By Moureen Awori – IITA-Uganda Overall Goal To consolidate stability in Northern Uganda, eradicate poverty and under-nutrition and strengthen the foundations for sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development Project duration and funding Introduction Under the Development Initiative for Northern Uganda Total duration: 36 months (2020 - 2022) (DINU), a Government of Uganda programme supported Total budget: Euros 5,578,949 by the European Union and supervised by Office of the European Union (90%): Euros 5,021,054 Prime Minister, International Institute of Tropical Consortium (10%): Euros 557,895 Agriculture (IITA) has received a grant to implement the action, “Building resilience to enhance food and nutrition Target group security, incomes and health in Northern Uganda”. The project to be implemented by a consortium of partners, Smallholder farmer households with access to land seeks to enhance food and nutrition security, increase ≥1.5 acres, households that produce at least one household incomes and improve maternal and child target commercial commodities, farmer groups nutrition and health in Northern Uganda (NU) by and cooperatives, women of reproductive age (15- promoting diversified food production of resilient 49 years), children (6-24 months), adolescents (10 varieties, commercializing agriculture, encouraging -

E Cacy and Safety of Artemether-Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Plasmodium Fa

Ecacy and Safety of Artemether-Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine for The Treatment of Uncomplicated Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria and Prevalence of Molecular Markers Associated With Artemisinin and Partner Drug Resistance in Uganda Chris Ebong ( [email protected] ) Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Asadu Sserwanga Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Jane Frances Namuganga Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration James Kapisi Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Arthur Mpimbaza Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Samuel Gonahasa Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Victor Asua Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Sam Gudoi USAID's Malaria Action Program for Districts Ruth Kigozi USAID's Malaria Action Program for Districts James Tibenderana USAID's Malaria Action Program for Distrcits John Baptist Bwanika Malaria Consortium Bosco Agaba National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of health Uganda Denis Rubahika National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of Health Uganda Daniel Kyabayinze Page 1/25 National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of Health, Uganda Jimmy Opigo National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of health Uganda Rutazana Damian National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of Health Uganda Gloria Sebikaari U.S. Presidential Malaria Initiative, Uganda Kassahun Belay U.S President's Malaria Initiative Mame Niang U.S. President's Malaria Initiative Eric S. Halsey Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Leah F. Moriarty Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Naomi W. Lucchi Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Samaly S. Svigel Souza Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Sam L. Nsobya Makerere University Faculty of Medicine: Makerere University College of Health Sciences Moses R.