Status of Implementation of SDG 4 on Education : Is Uganda on Track?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

Uganda Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers (Ugift) Programme

UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME Front View of the completed Upgraded Pandwong HC Front View of the Science Laboratory under Construction III, Kitgum Municipal Council at Kimenyedde Seed Secondary School, Mukono District The 2nd Joint Monitoring of Seed Secondary Schools and Upgrade of Health Centre IIs to III conducted from 27th July – 7th August, 2020 Final Report October 2020 MOFPED MofpedU #DoingMore 1 UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME Front View of the completed Upgraded Pandwong HC III, Kitgum Front View of the Science Laboratory under Construction at Municipal Council Kimenyedde Seed Secondary School, Mukono District The 2nd Joint Monitoring of Seed Secondary Schools and Upgrade of Health Centre IIs to III conducted from 27th July – 7th August, 2020 Final Report October 2020 UGANDA INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL TRANSFERS (UGIFT) PROGRAMME Table of Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables v Acronyms vi Foreword 1 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2.0 THE SECOND(2ND) JOINT MONITORING EXERCISE 3 2.1 Background and objectives 3 2.2 The Joint Monitoring approach 4 2.2.1 Team Composition 4 2.2.2 Objectives of the Joint Monitoring 4 2.2.3 The Second Joint Monitoring Programme 4 2.2.4 Projects Monitored 4 2.2.5 Monitoring, Reporting and Data Analysis tools 5 FINDINGS FROM THE 2ND JOINT MONITORING EXERCISE 6 3.0 SEED SECONDARY SCHOOLS 6 3.1 Contract Management 6 3.1.1 Validity of contracts for on-going Seed Secondary -

Message from DGF Welcome to Yet Another Issue of the Special Newsletter on Our Implementing Partners’ Response to Governance Issues Related to the COVID-19 Outbreak

Message from DGF Welcome to yet another issue of the special newsletter on our implementing partners’ response to governance issues related to the COVID-19 outbreak. In this issue, we continue to share with you the various interventions and innovations our partners are pursuing to strengthen governance in Uganda, amidst the outbreak of corona virus. SPECIAL NEWSLETTER ON DGF IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS’ In responding to the challenges caused RESPONSE TO COVID-19, ISSUE 3, JULY 2020 by COVID-19 related restriction on their programme operations, many of our partners have adopted new Women Organisations Caution the Electoral Commission on approaches to their programming in order to adhere to the Ministry of Using Media as the Only Campaign Platform for 2021 Elections Health guidelines on COVID-19. forthcoming campaigns because they lead to huge congregations and physical contacts For example, some of our partners have opted for online technologies known for spreading the COVID-19. and various media channels to engage with their beneficiaries on issues At the press conference, UWONET such as prevention of COVID-19; noted that whereas they appreciate the accountability for COVID-19 resources; gender-based violence; leadership creativity of the EC in organising a scientific and governance; access to service election given the unprecedented times delivery; and citizens’ rights, roles and Representatives of women organisatons address of COVID-19, they are concerned that responsibilities, among others. journalists at a Press Conference in Kampala. ‘digitalising elections’ might combine with (Source: UWONET) pre-existing inequalities to undermine We appreciate our partners for the commendable work they are doing omen organisations through their women, youth and rural populations from even during these uncertain times network, the Uganda Women’s participating in the forthcoming election, to ensure continuation of their WNetwork (UWONET), held a press both as voters and candidates. -

PEPFAR Uganda Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019

PEPFAR Uganda Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary April 12, 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement .................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context ....................................................................... 7 2.1 Summary Statistics, Disease Burden and Country Profile ................................................. 7 2.2 Investment Profile ............................................................................................................................. 19 2.3 National Sustainability Profile Update .............................................................................................. 24 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR Investments Geographically to Disease Burden ............................................ 28 2.5 Stakeholder Engagement .................................................................................................................. 29 3.0 Geographic and Population Prioritization ...................................................................... 32 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-Up Locations and Populations .. 33 4.1 Finding the missing, getting them on treatment, and retaining them ensuring viral suppression .. 34 4.2 Prevention, specifically detailing programs for priority programming: ........................................... 52 4.2.a. OVC and Child-Focused COP19 Interventions .......................................................................... -

Developed Special Postcodes

REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF INFORMATION & COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AND NATIONAL GUIDANCE DEVELOPED SPECIAL POSTCODES DECEMBER 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS KAMPALA 100 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 EASTERN UGANDA 200 ........................................................................................................................... 5 CENTRAL UGANDA 300 ........................................................................................................................... 8 WESTERN UGANDA 400 ........................................................................................................................ 10 MID WESTERN 500 ................................................................................................................................ 11 WESTNILE 600 ....................................................................................................................................... 13 NORTHERN UGANDA 700 ..................................................................................................................... 14 NORTH EASTERN 800 ............................................................................................................................ 15 KAMPALA 100 No. AREA POSTCODE 1. State House 10000 2. Parliament Uganda 10001 3. Office of the President 10002 4. Office of the Prime Minister 10003 5. High Court 10004 6. Kampala Capital City Authority 10005 7. Central Division 10006 -

Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) the REPUBLIC of UGANDA OFFICE of the PRIME MINISTER EUROPEAN UNION

Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER EUROPEAN UNION Building resilience to enhance food and nutrition security, income and health in Northern Uganda (BRENU) By Moureen Awori – IITA-Uganda Overall Goal To consolidate stability in Northern Uganda, eradicate poverty and under-nutrition and strengthen the foundations for sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development Project duration and funding Introduction Under the Development Initiative for Northern Uganda Total duration: 36 months (2020 - 2022) (DINU), a Government of Uganda programme supported Total budget: Euros 5,578,949 by the European Union and supervised by Office of the European Union (90%): Euros 5,021,054 Prime Minister, International Institute of Tropical Consortium (10%): Euros 557,895 Agriculture (IITA) has received a grant to implement the action, “Building resilience to enhance food and nutrition Target group security, incomes and health in Northern Uganda”. The project to be implemented by a consortium of partners, Smallholder farmer households with access to land seeks to enhance food and nutrition security, increase ≥1.5 acres, households that produce at least one household incomes and improve maternal and child target commercial commodities, farmer groups nutrition and health in Northern Uganda (NU) by and cooperatives, women of reproductive age (15- promoting diversified food production of resilient 49 years), children (6-24 months), adolescents (10 varieties, commercializing agriculture, encouraging -

E Cacy and Safety of Artemether-Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Plasmodium Fa

Ecacy and Safety of Artemether-Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine for The Treatment of Uncomplicated Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria and Prevalence of Molecular Markers Associated With Artemisinin and Partner Drug Resistance in Uganda Chris Ebong ( [email protected] ) Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Asadu Sserwanga Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Jane Frances Namuganga Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration James Kapisi Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Arthur Mpimbaza Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Samuel Gonahasa Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Victor Asua Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration Sam Gudoi USAID's Malaria Action Program for Districts Ruth Kigozi USAID's Malaria Action Program for Districts James Tibenderana USAID's Malaria Action Program for Distrcits John Baptist Bwanika Malaria Consortium Bosco Agaba National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of health Uganda Denis Rubahika National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of Health Uganda Daniel Kyabayinze Page 1/25 National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of Health, Uganda Jimmy Opigo National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of health Uganda Rutazana Damian National Malaria Control Division, Ministry of Health Uganda Gloria Sebikaari U.S. Presidential Malaria Initiative, Uganda Kassahun Belay U.S President's Malaria Initiative Mame Niang U.S. President's Malaria Initiative Eric S. Halsey Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Leah F. Moriarty Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Naomi W. Lucchi Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Samaly S. Svigel Souza Malaria Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & President's Malaria Initiative Atlanta, Georgia Sam L. Nsobya Makerere University Faculty of Medicine: Makerere University College of Health Sciences Moses R. -

Annual State of Disaster Report (ASDR)

www.necoc-opm.go.ug || [email protected] || www.necoc-opm.go.ug The crunch 2020 year (ASDR). Disaster Report of State Annual A tale of anguish wrapped in a blessing Scan code to read the ASDR Online ASDR- 2020 || [email protected] || www.necoc-opm.go.ug ASDR - 2020 Know Your Risk We live with risk! But do we Know it? Do we understand it? Annual State of Disaster Report 2020. Drawing: A mental illustration of a flood and elements at risk - Dara, a 6 year old. Publisher: Office of the Prime Minister The inaugural Report Published by: Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management Photographs: DRDPM & credited sources Design & Production: Ms Pamela Komujuni-Kalule, Lt. Stanley Osaba, Mr Sandro Semedo, WO II Babeiha Wycliffe and Mr Justin Dralaze (ScreenSmith) © 2020 Office of the Prime Minister 5th floor, Postel Building, Clement Hill Road. P.O Box 341, Kampala Uganda. Tel No. 0414 342 104 Toll free line: 0800 177 777 The inaugural Report Email: [email protected] Website: www.necoc-opm.go.ug Twitter: @OPMUganda | @dpmopm Office of the Prime Minister ASDR 2020 i | | ii ASDR- 2020 || [email protected] || www.necoc-opm.go.ug ASDR - 2020 Contents List of Acronyms Annual State of Disaster Report The inaugural Report ASDR PREFATORY REMARKS THE COMPLEX SHIFT COVID Corona Virus Disease SECTORAL IMPACTS CSO Civil Society Organisation Forward iii COVID 19 Pandemic - A tale of tension and Disaster impacts by sub region 13 Chapter unprecedented uncertainty 69 DCP District Contingency Plan Opening Note v DRDPM Department of Relief, -

Articles More Effectively Than Exotic Trees

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ON-FARM APPROACHES FOR CONSERVATION OF INDIGENOUS TREE SPECIES AMONG HOUSEHOLDS IN ABOKO PARISH KWANIA DISTRICT BY ADUPA ISAAC 16/U/20515/PS 216022315 A REPORT SUBMITTED IN THE PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE REQUIREMENT OF THE AWARD OF A BACHELORS DEGREE IN SOCIAL AND ENTREPRENUERIAL FORESTRY OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2019 i i DEDICATION I dedicate this study report to my father Mr. OKWIR TOM, all our family members, Mujibhai Madhvani Group of Company and friends who have been too supportive towards accomplishment of the study. I also dedicate this work to my Lecturers and Instructors at the School of Forestry, Environmental and Geographical Sciences for their support and continued guidance. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The study had to be a success because of the contributions from several institutions and individuals. At the institutional level, I am greatly indebted to University for taking me as a graduate student. This enabled me realize the dream of pursuing a graduate program. Special mention also goes to the Department of Forestry, Biodiversity and tourism for availing field specific literature and facilitating me through the library and computer laboratory within the department. Without the department's assistance, the fieldwork would have been a nightmare. At the individual level, many thanks are due to my supervisors, Associate Professor John Bosco Lamoris Okullo for his tireless guidance, encouragement and constructive criticisms. His input has been indispensable in improving the quality of this work. I owe special mention to all the farmers interviewed for cooperation. I also thank my fellow students whose generous assistance enabled me share their vast knowledge and experience in agro forestry practices. -

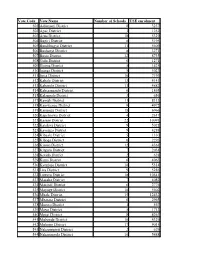

Vote Code Vote Name Number of Schools USE Enrolment 501

Vote Code Vote Name Number of Schools USE enrolment 501 Adjumani District 8 3237 502 Apac District 3 1252 503 Arua District 18 5329 504 Bugiri District 8 5195 505 Bundibugyo District 11 5609 506 Bushenyi District 8 3271 507 Busia District 12 8735 508 Gulu District 6 1271 509 Hoima District 5 1425 510 Iganga District 5 5023 511 Jinja District 10 7193 512 Kabale District 13 4143 513 Kabarole District 11 4882 514 Kaberamaido District 6 1865 515 Kalangala District 3 656 517 Kamuli District 11 8313 518 Kamwenge District 9 4972 519 Kanungu District 18 6966 520 Kapchorwa District 4 2617 521 Kasese District 22 10091 522 Katakwi District 9 5021 523 Kayunga District 9 4288 524 Kibaale District 5 1330 525 Kiboga District 6 2293 526 Kisoro District 12 4361 527 Kitgum District 7 2034 528 Kotido District 2 628 529 Kumi District 6 4063 530 Kyenjojo District 10 5314 531 Lira District 9 5286 532 Luwero District 18 10541 533 Masaka District 7 4082 534 Masindi District 6 2776 535 Mayuge District 10 5602 536 Mbale District 15 12432 537 Mbarara District 6 2965 538 Moroto District 1 567 539 Moyo District 5 1713 540 Mpigi District 8 4263 541 Mubende District 10 4329 542 Mukono District 17 9015 543 Nakapiripirit District 2 629 544 Nakasongola District 10 5488 545 Nebbi District 5 2257 546 Ntungamo District 18 8412 547 Pader District 8 2856 548 Pallisa District 8 6661 549 Rakai District 14 7586 550 Rukungiri District 21 11111 551 Sembabule District 8 4162 552 Sironko District 10 5552 553 Soroti District 5 3421 554 Tororo District 17 13341 555 Wakiso District 14 -

LANGO INVESTMENT PROFILE of Particular Note Is the Strategic Location of the Region in Northern Uganda

www.ugandainvest.go.ug Invest in Lango Background This investment profile is aimed at promoting the potential of the Greater Lango region so as to propel its economic potential and attract both local and foreign investors to stimulate the development of the region. The profile takes a multi-sectoral analysis approach so as to support the relevant value chains players in harnessing the different opportunities. The sectors of focus are those which are positioned to develop the region such as agriculture (and agro-processing), tourism, trade, manufacturing and services such as education, health and finances. There are some incentives which specific districts are willing to give investors such as industrial and agricultural land for easy location of their businesses. These can be coupled with the National incentives especially for investors willing to set up upcountry. The Lango sub-region is currently divided into 9 districts of Alebtong, Amolatar, Apac, Dokolo, Kole, Lira, Oyam, Otuke and Kwania District. It’s a relatively urbanized region with two Municipalities in Lira and Apac districts where manufacturing, trade and services are evidently booming. The region is situated within the annual cropping and cattle-farming systems that are primarily found in Northern Uganda. The region is dry compared to the rest of the country and experiences one long rainy season also called the unimodal type of rainfall, yet farmers can still grow two crops in a year. The country’s grain basket and in fact contributing to the GDP. The profile shows the crucial facilitating role played by both the Government agencies and local authorities whose main role is to propel Local Economic Development. -

Uganda Voucher Plus Activity Quarterly Report Year 4, Quarter 4 July – September 2019

1 Uganda Voucher Plus Activity Quarterly Report Year 4, Quarter 4 July – September 2019 Re-submission date: 4 November 2019 Submission Date: 31 October 2019 Number: AID-617-LA-16-00001 Activity Start Date and End Date: January 29, 2016 to September 30, 2020 Name: Dr. Christine Mugasha Submitted by: Christine Namayanja, Chief of Party Abt Associates 6130 Executive Boulevard Rockville, MD 20850, USA Tel: +1-301-347-5000 Email: [email protected] Copied to: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development Uganda USAID|Uganda Mission (USAID/Voucher PlusUganda Activity). Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... iii Activity Information .......................................................................................................................... iv 1. Activity Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Activity Description ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Performance Analysis to Date .............................................................................................................. 2 2. Activity Implementation Progress ......................................................................................... 6 2.1 Summary of Implementation