THE NABATAEANS and LYCIANS Zeyad Al-Salameen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Political Sociology of the Imperial Greek City Arjan Zuiderhoek

On the Political Sociology of the Imperial Greek City Arjan Zuiderhoek But above all things, we must remind them that being a pol- itician consists not only in holding office, being ambassador, vociferating in the assembly and ranting round the speakers’ platform proposing laws and motions. Most people think all that is part of being a politician, just as they think of course that those are philosophers who sit in a chair and converse and prepare their lectures over their books. HUS WROTE PLUTARCH in his essay Whether an old man should engage in public affairs.1 It seems an offhand remark, T but all the more interesting for that. For here we have a comment on contemporary Greek civic politics, written prob- ably sometime in the first two decades of the second century, in which the activities of the Greek politicians of the day are described in terms (“vociferating in the assembly,” “ranting around the speaker’s platform”) at least to some extent rem- iniscent of the political world of democratic Athens centuries earlier. It is a description that does not quite seem to fit the common scholarly depiction of the later Hellenistic and Roman Greek cities as strongly oligarchic societies, dominated socially and politically by small coteries of (often interrelated) elite families whose governing institution of choice was the boule, the city council.2 This, then, prompts the question: which of these two contrasting images is nearer the truth? Should we dismiss Plutarch’s remarks as merely another manifestation of 1 Mor. 796C–D (transl. Fowler, modified). 2 See most recently M. -

Georgy Kantor

Georgy Kantor Lycia et Pamphylia: A Social and Institutional History The project which I am proposing to undertake is a social and institutional history of the Roman province of Lycia and Pamphylia, from the process of establishment of Roman rule in the region in the late Republic and the Julio-Claudian period to the coming of Christianity and the separation of the constituent parts of the province in the early fourth century AD. The project aims at utilising different kinds of evidence – documentary, archaeological, numismatic, literary. Several factors combine to make such a study worthwhile. The isolated nature of the region, separated as it is by mountain ranges from the rest of Anatolia, and the fact that, with a very brief interruption, it has been a single administrative unit for more than two centuries, from the principate of Claudius to at least AD 312, allow us to treat it as a meaningful object of regional history. But below this unity there were striking distinctions between its different parts. In the course of my doctoral work on Roman and local law in the provinces of Asia Minor, I have found preliminary evidence to indicate that the ways in which Pamphylia and Lycia were governed by Rome were different in many crucial aspects. My project will thus provide an opportunity to study two models of Roman rule within one province, and it is at this level that we can best understand how Roman imperial structures worked and contribute to the ongoing discussion (re-opened by recent works of S. Dmitriev and C. -

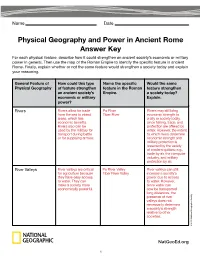

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

295 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA and the ROMAN EMPIRE

EMANUELA BORGIA, CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2017.16.15 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE: REFLECTIONS ON PROVINCIA CILICIA AND ITS ROMANISATION Abstract This paper aims at the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long (from the 1st century BC to 72 AD) and complicated by various events. Firstly, it will focus on a more precise determination of the geographic limits of the region, which are not clear and quite ambiguous in the ancient sources. Secondly, the author will thoroughly analyze the formation of the province itself and its progressive Romanization. Finally, political organization of Cilicia within the Roman empire in its different forms throughout time will be taken into account. Key words Cilicia, provincia Cilicia, Roman empire, Romanization, client kings 295 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 · ROME AND THE PROVINCES Quos timuit superat, quos superavit amat (Rut. Nam., De Reditu suo, I, 72) This paper attempts a systematic approach to the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long and characterized by a complicated sequence of historical and political events. The main question is formulated drawing on – though in a different geographic context – the words of G. Alföldy1: can we consider Cilicia a „typical” province of the Roman empire and how can we determine the peculiarities of this province? Moreover, always recalling a point emphasized by G. Alföldy, we have to take into account that, in order to understand the characteristics of a province, it is fundamental to appreciate its level of Romanization and its importance within the empire from the economic, political, military and cultural points of view2. -

Building Materials and Techniqu63 in the Eastern

BUILDING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQU63 IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN FRUM THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD TO THE FOURTH CENTURY AD by Hazel Dodgeq BA Thesis submitted for the Degree of'PhD at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne Decembert 1984 "When we buildq let us thinjc that we build for ever". John Ruskin (1819 - 1900) To MY FAMILY AND TU THE MEMORY OF J. B. WARD-PERKINS (1912 - 1981) i ABSTRACT This thesis deals primarily with the materials and techniques found in the Eastern Empire up to the 4th century AD, putting them into their proper historical and developmental context. The first chapter examines the development of architecture in general from the very earliest times until the beginnin .g of the Roman Empire, with particular attention to the architecture in Roman Italy. This provides the background for the study of East Roman architecture in detail. Chapter II is a short exposition of the basic engineering principles and terms upon which to base subsequent despriptions. The third chapter is concerned with the main materials in use in the Eastern Mediterranean - mudbrick, timber, stone, mortar and mortar rubble, concrete and fired brick. Each one is discussed with regard to manufacture/quarrying, general physical properties and building uses. Chapter IV deals with marble and granite in a similar way but the main marble types are described individually and distribution maps are provided for each in Appendix I. The marble trade and the use of marble in Late Antiquity are also examined. Chapter V is concerned with the different methods pf wall construction and with the associated materials. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

CHAP'IERTWO THE LYCIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography and communications in Lycia1 Lycia lies on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, between Caria and Pam phylia. At the period of its smallest extent, at the time of the Persian con quest, the Lycian state covered an area comparable in size to Attica, ex tending over most of the territory of the Xanthos valley, probably as far north as Araxa, more than forty kilometres away from Xanthos, and nearly fifty from the Mediterranean; Bryce has argued that to Homer 'Lycia' meant no more than the Xanthos valley. 2 At its largest, under Perikle of Limyra (pp. 154-70), the Lycian state was comparable in size to the south ern Peloponnese (i.e. Laconia and Messenia), stretching from Phaselis in the east to Telemessos in the north-west, nearly a hundred and thirty kilo metres as the crow flies, and included a large section of southern Milyas, if not all of it (p. 20). It is separated from its neighbours by high mountains which hampered movement in antiquity. 3 This remoteness continued into modern times-when Bean first visited the area in 1946 he found a country where tractors were unknown, and: When I asked, 'What do you do in the winter?', the answer was, 'We sit'.4 Three great chains determine access to and within Lycia. In the west two spurs of the western Tauros, the Boncuk Daglan and the Baba Dag1 (this latter being ancient Mt. Kragos and Mt. Antikragos) restrict access to Ly cia to the pass between them, east of Telemessos. -

Mortem Et Gloriam Army Lists Use the Army Lists to Create Your Own Customised Armies Using the Mortem Et Gloriam Army Builder

Army Lists Syria and Asia Minor Contents Asiatic Greek 670 to 129 BCE Lycian 525 to 300 BCE Bithynian 434 to 74 BCE Armenian 330 BCE to 627 CE Asiatic Successor 323 to 280 BCE Cappadocian 300 BCE to 17 CE Attalid Pergamene 282 to 129 BCE Galatian 280 to 62 BCE Early Seleucid 279 to 167 BCE Seleucid 166 to 129 BCE Commagene 163 BCE to 72 CE Late Seleucid 128 to 56 BCE Pontic 110 to 47 BCE Palmyran 258 CE to 273 CE Version 2020.02: 1st January 2020 © Simon Hall Creating an army with the Mortem et Gloriam Army Lists Use the army lists to create your own customised armies using the Mortem et Gloriam Army Builder. There are few general rules to follow: 1. An army must have at least 2 generals and can have no more than 4. 2. You must take at least the minimum of any troops noted and may not go beyond the maximum of any. 3. No army may have more than two generals who are Talented or better. 4. Unless specified otherwise, all elements in a UG must be classified identically. Unless specified otherwise, if an optional characteristic is taken, it must be taken by all the elements in the UG for which that optional characteristic is available. 5. Any UGs can be downgraded by one quality grade and/or by one shooting skill representing less strong, tired or understrength troops. If any bases are downgraded all in the UG must be downgraded. So Average-Experienced skirmishers can always be downgraded to Poor-Unskilled.