Preparation and Properties of Isolated Z-Disks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skeletal Muscle Tissue in Movement and Health: Positives and Negatives Stan L

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2016) 219, 183-188 doi:10.1242/jeb.124297 REVIEW Skeletal muscle tissue in movement and health: positives and negatives Stan L. Lindstedt* ABSTRACT This observation prompted the Swiss scientist von Haller (credited ‘ ’ The history of muscle physiology is a wonderful lesson in ‘the as the Father of Neurobiology ) to suggest that it was irritability, not scientific method’; our functional hypotheses have been limited by a humor, which is transmitted to the muscle through the nerve. For a our ability to decipher (observe) muscle structure. The simplistic wonderful comprehensive examination of muscle history, the ‘ ’ understanding of how muscles work made a large leap with the definitive source is the book Machina Carnis by Needham (1971). remarkable insights of A. V. Hill, who related muscle force and power The first Professor of Physiology in the USA (Columbia to shortening velocity and energy use. However, Hill’s perspective University) was the Civil War surgeon J. C. Dalton, who authored ‘ was largely limited to isometric and isotonic contractions founded on the first USA textbook of physiology ( Treatise on Human ’ isolated muscle properties that do not always reflect how muscles Physiology ). He observed that irritability (which he noted could function in vivo. Robert Josephson incorporated lengthening be triggered with an electric shock) is an inherent property of the ‘ ’ contractions into a work loop analysis that shifted the focus to muscle fiber, not communicated to it by other parts (Dalton, ‘ ’ dynamic muscle function, varying force, length and work done both 1864). The consequence of this irritability is that muscles produce by and on muscle during a single muscle work cycle. -

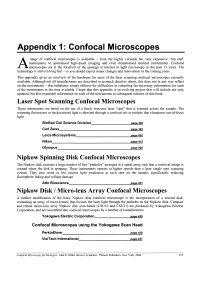

Appendix 1: Confocal Microscopes

Appendix 1: Confocal Microscopes range of confocal microscopes is available - from the highly versatile but very expensive "top end" A instruments, to specialised high-speed imaging and even miniaturised medical instruments. Confocal microscopes are at the forefront of the upsurge in interest in light microscopy in the past 15 years. The technology is still evolving fast - so you should expect major changes and innovations in the coming years. This appendix gives an overview of the hardware for most of the laser scanning confocal microscopes currently available. Although not all manufacturers are described in as much detail as others, this does not in any way reflect on the instruments - this imbalance simply reflects the difficulties in compiling the necessary information for each of the instruments in the time available. I hope that this appendix is an evolving project that will include not only updated, but also expanded information on each ofthe instruments in subsequent editions ofthis book. Laser Spot Scanning Confocal Microscopes These instruments are based on the use of a finely focussed laser "spot" that is scanned across the sampie. The retuming fluorescent or backscattered light is directed through a confocal iris or pinhole that eliminates out-of-focus light. BioRad Cell Science Division _________--'pO<:a..,g.."ec..::3=56 CarIZeiss___________________ p~a~gce~3~8~2 Leica Microsystems_____________ ---"p~a!.llg~e..:!:4=02 Nikon________________________________________ ~p~aAg~e~4~15 Olympus___________________ ~p~a~gce~4~2~O Nipkow Spinning Disk Confocal Microscopes The Nipkow disk contains a large number of fine "pinholes" arranged in a spiral array such that a confocal image is created when the disk is spinning. -

Power and Efficiency of Insect Flight Muscle

J. exp. Biol. 115, 293-304 (1985) 293 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists limited 1985 POWER AND EFFICIENCY OF INSECT FLIGHT MUSCLE BY C. P. ELLINGTON Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, England SUMMARY The efficiency and mechanical power output of insect flight muscle have been estimated from a study of hovering flight. The maximum power output, calculated from the muscle properties, is adequate for the aerodynamic power requirements. However, the power output is insufficient to oscillate the wing mass as well unless there is good elastic storage of the inertial energy, and this is consistent with reports of elastic components in the flight system. A comparison of the mechanical power output with the metabolic power input to the flight muscles suggests that the muscle efficiency is quite low: less than 10%. INTRODUCTION In recent years the mechanical analysis of animal locomotion has become increasingly sophisticated, resulting in accurate estimates of the sustained, aerobic mechanical power output required of the locomotor muscles. These estimates have been compared with the metabolic power input, as measured by the rate of oxygen consumption, to determine the muscle efficiency. Two major studies, one on running birds and mammals (Heglund, Fedak, Taylor & Cavagna, 1982) and the other on hovering insects (Ellington, 1984), have both concluded that the muscle efficiency can be much lower than the commonly expected 20-30%. The results for terrestrial locomotion are discussed elsewhere in this volume (Heglund, 1985), and I shall review the power and efficiency of insect flight muscle during hovering, a type of flight so energetically demanding that only hummingbirds and insects can sustain it aerobically. -

Molecular Cloning, Expression, and Protein Interaction of Avian Muscle Titin Kuan Onn Tan Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1993 Molecular cloning, expression, and protein interaction of avian muscle titin Kuan Onn Tan Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Biochemistry Commons, and the Molecular Biology Commons Recommended Citation Tan, Kuan Onn, "Molecular cloning, expression, and protein interaction of avian muscle titin " (1993). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10555. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10555 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U'M'I MICROFILMED 1994 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Mechanics of the Thorax in Flies Tanvi Deora1, Namrata Gundiah2 and Sanjay P

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 1382-1395 doi:10.1242/jeb.128363 REVIEW Mechanics of the thorax in flies Tanvi Deora1, Namrata Gundiah2 and Sanjay P. Sane1,* ABSTRACT body size, which greatly facilitated adaptability by increasing their Insects represent more than 60% of all multicellular life forms, and are ecological range; and two, the evolution of flight, which enabled easily among the most diverse and abundant organisms on earth. dispersal, migration, predation or rapid escape from predator They evolved functional wings and the ability to fly, which enabled attacks. them to occupy diverse niches. Insects of the hyper-diverse orders Although miniature body forms are a common evolutionary trend show extreme miniaturization of their body size. The reduced body among other animals, including birds and mammals (e.g. Hanken size, however, imposes steep constraints on flight ability, as their and Wake, 1993), miniaturization takes on a rather extreme form in wings must flap faster to generate sufficient forces to stay aloft. Here, insects. For example, the size of adult parasitic chalcid wasps such ∼ we discuss the various physiological and biomechanical adaptations as Kikiki huna ( 150 µm) or the trichogrammatid wasp ∼ of the thorax in flies which enabled them to overcome the myriad Megaphragma mymaripenne ( 170 µm) is comparable to that of constraints of small body size, while ensuring very precise control of some unicellular protozoan organisms (Polilov, 2012, 2015); these their wing motion. One such adaptation is the evolution of specialized wasps are among the smallest metazoans ever described. Such myogenic or asynchronous muscles that power the high-frequency extreme miniaturization is especially common among parasitoid – wing motion, in combination with neurogenic or synchronous steering insects belonging to three of the five insect groups Diptera (flies), – muscles that control higher-order wing kinematic patterns. -

Submaximal Power Output from the Dorsolongitudinal Flight Muscles Of

The Journal of Experimental Biology 207, 4651-4662 4651 Published by The Company of Biologists 2004 doi:10.1242/jeb.01321 Submaximal power output from the dorsolongitudinal flight muscles of the hawkmoth Manduca sexta Michael S. Tu* and Thomas L. Daniel Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195-1800, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 1 October 2004 Summary To assess the extent to which the power output of a generated only 40–67% of their maximum potential power synchronous insect flight muscle is maximized during output. Compared to the in vivo phase of activation, the flight, we compared the maximum potential power output phase that maximized power output was advanced by of the mesothoracic dorsolongitudinal (dl1) muscles of 12% of the cycle period, and the length that maximized Manduca sexta to their power output in vivo. Holding power output was 10% longer than the in vivo operating temperature and cycle frequency constant at 36°C and length. 25·Hz, respectively, we varied the phase of activation, mean length and strain amplitude. Under in vivo conditions measured in tethered flight, the dl1 muscles Key words: flight, muscle, work, power, Manduca sexta. Introduction Over the last two decades, work loop studies have provided generation by the deep red trunk muscle of swimming skipjack new insights into the principles of design that underlie muscle tuna (Syme and Shadwick, 2002). The unique anatomical performance. In particular, a growing number of studies have arrangement of the red muscle of skipjack tuna and other compared maximal power output under experimental thunniform swimmers may be critical in allowing these conditions to realized power output in vivo. -

V·M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howellinformanon Company 300 North Zeeb Road

The structure, function, and metamorphic reorganization of the abdominal stretch receptor organ in Manduca sexta. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tamarkin, Dawn Alene Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 09:25:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/186168 Thi"FORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fro~ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedtbrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

II M.Sc., Zoology Elective Paper III. General Entomology Dr. M

Government Arts College. Coimbatore-641 018 Department of Zoology. II M.Sc., Zoology Elective paper III. General Entomology Dr. M. Muthusamy Unit. IV. Insect Muscular System, Skeletal Muscles, Visceral Muscles, Energetic’s Of Muscle Contraction, Insect Muscle • The muscular system of insects ranges from a few hundred muscles to a few thousand. Unlike vertebrates that have both smooth and striated muscles, insects have only striated muscles. Muscle cells are amassed into muscle fibers and then into the functional unit, the muscle.[6 Muscles are attached to the body wall, with attachment fibers running through the cuticle and to the epicuticle, where they can move different parts of the body including appendages such as wings.The muscle fiber has many cells with a plasma membrane and outer sheath or sarcolemma. • The sarcolemma is invaginated and can make contact with the tracheole carrying oxygen to the muscle fiber. Arranged in sheets or cylindrically, contractile myofibrils run the length of the muscle fiber. Myofibrils comprising a fine actin filament enclosed between a thick pair of myosin filaments slide past each other instigated by nerve impulses. • Visceral: these muscles surround the tubes and ducts and produce peristalsis as demonstrated in the digestive system. • Segmental: causing telescoping of muscle segments required for moulting, increase in body pressure and locomotion in legless larvae. • Appendicular: originating from either the sternum or the tergum and inserted on the coxae these muscles move appendages as one unit.[ These are arranged segmentally and usually in antagonistic pairs. Appendage parts of some insects, e.g. the galea and the lacinia of the maxillae, only have flexor muscles. -

Chapter 11 Differential Interference Contrast Microscopy © C

Chapter 11 DIC Chapter 11 Differential Interference Contrast Microscopy © C. Robert Bagnell, Jr., Ph.D., 2012 Many microscopic specimens are colorless, nearly transparent, and relatively thick, such as tissue sections. This chapter presents a method for producing contrast in this type of specimen without the artifacts associated with phase contrast. The resulting image is one that has a very “topographic” appearance. It looks as though you are looking down on the specimen while it is being lit strongly from one side. Figure 11.0 is a DIC image of cheek epithelial cells. Figure 11.0 DIC of Cheek Epithelial Cells Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) is optically a rather complicated method requiring several special optical components. These are described and their action in producing this beautiful image is discussed in the following sections. Types of Specimens Suitable for DIC Those specimens that would be suitable for phase contrast microscopy are also suitable for DIC. Furthermore, DIC produces clearer images of relatively thick specimens than does phase contrast. Cytological, histological, microbiological, and cell culture specimens are of this type as are chromosome spreads. DIC is especially useful in fluorescence and confocal microscopy to indicate the morphological aspect of fluorescent regions. DIC reveals some ultrastructural features of cells such as microtubules and cytoplasmic granules. When coupled with enhanced video techniques, DIC enables the visualization of actin structures that are actually below the resolution of the microscope. Finally, the use of DIC on normal, stained or unstained histological sections can provide additional useful information. Pathology 464 – Light Microscopy 1 Chapter 11 DIC History of DIC We owe the current method of DIC to the work of Georges Nomarski (figure 11.1) who developed it in the 1960’s. -

Microscopes UMDNS #: 12536 Date of Creation: October 29, 2015 Creator: Complied by Cassandra Stanco for Engineering World Health (EWH)

Equipment Packet: Microscopes UMDNS #: 12536 Date of Creation: October 29, 2015 Creator: Complied by Cassandra Stanco for Engineering World Health (EWH) Equipment Packet Contents: This packet contains information about the operation, maintenance, and repair of laboratory microscopes. Part I: External From the Packet: 1. An Introduction to Microscopes: PowerPoint Part II: Included in this Packet: 1. Operation and Use: a. Introduction to Optical Microscopes (p. 3-12) b. Operation and Use of Microscopes (p. 13-20) 2. Diagrams and Schematics: a. Figure 1: Diagram of a Light Microscope (p. 22) b. Figure 2: Diagram and Parts of a Compound Light Microscope (p. 23) 3. Preventative Maintenance and Safety: a. Microscope Preventative Maintenance (p. 25) 4. Troubleshooting and Repair: a. Microscope Repair and Troubleshooting Flowchart (p. 27-29) 5. Resources for More Information a. Resources for More Information (p. 31) b. Bibliography (p. 32) * * * * 1.*Operation*and*Use*of*Microscopes* * * * Featured*in*this*Section:* * * * WHO.)“Learning)Unit)6:)The)Microscope.”)From)the)Publication:)Basic(Malaria(Microscopy:(part(1.(A( Learner’s(Guide.)WHO:)Switzerland)(2010),)p.)37_44.)Retrieved)from:) http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44208/1/9789241547826_eng.pdfhttp://apps.who. int/iris/bitstream/10665/44208/1/9789241547826_eng.pdf) * * * ) * * * * Optical microscope 1 Optical microscope The optical microscope, often referred to as the "light microscope", is a type of microscope which uses visible light and a system of lenses to magnify images of small samples. Optical microscopes are the oldest and simplest of the microscopes. Digital microscopes are now available which use a CCD camera to examine a sample, and the image is shown directly on a computer screen without the need for optics such as eye-pieces. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427817 Analysis of the in vivo role of myosin regulatory light chain phosphory lat ion Tohtong, Rutaiwan, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1994 UMI 300 N. -

The Whistle and the Rattle: the Design of Sound Producing Muscles (Rattlesnake/Toadfish/Calcium Transients/Muscle Mechanics/Swimbladder) LAWRENCE C

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 93, pp. 8095-8100, July 1996 Physiology The whistle and the rattle: The design of sound producing muscles (rattlesnake/toadfish/calcium transients/muscle mechanics/swimbladder) LAWRENCE C. ROME*tt, DOUGLAS A. SYME*, STEPHEN HOLLINGWORTH§, STAN L. LINDSTEDT$, AND STEPHEN M. BAYLOR§ Departments of *Biology and §Physiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; tMarine Biological Laboratories, Woods Hole, MA 02543; and IDepartment of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011 Communicated by Clara Franzini-Armstrong, University of Pennsylvania School ofMedicine, Philadelphia, PA, April 15, 1996 (received for review December 11, 1995) ABSTRACT Vertebrate sound producing muscles often sients-in fact the largest and fastest ever recorded. How- operate at frequencies exceeding 100 Hz, making them the ever, our results showed that a fast Ca2+ transient alone is fastest vertebrate muscles. Like other vertebrate muscle, these not sufficient for high frequency operation. By measuring sonic muscles are "synchronous," necessitating that calcium Vmax, an index of crossbridge detachment rate, and the be released and resequestered by the sarcoplasmic reticulum force-pCa relationship in skinned fibers, a possible index of during each contraction cycle. Thus to operate at such high troponin kinetics, we found that rapid activation and relax- frequencies, vertebrate sonic muscles require extreme adap- ation likely also require a modification of the crossbridge tations. We have found that to generate the "boatwhistle" kinetic rate, and probably a modification of the kinetics of mating call (-200 Hz), the swimbladder muscle fibers of Ca2+-troponin binding. In reaching these conclusions, we toadfish have evolved (i) a large and very fast calcium first compared the above measurements in three fiber types transient, (ii) a fast crossbridge detachment rate, and (iii) from toadfish, ranging from slow twitch swimming fibers to probably a fast kinetic off-rate of Ca2+ from troponin.