Brief of Respondent for Fisher V. University of Texas at Austin; 11-345

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marshall News Vol 3 Issue 3 Feb 2007

TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY VOLUME 3 ISSUE 3 Marshall News M ARCH 19, 2007 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Black History Month — Meet the Law Library 2 Staff Remembering Our Past Clerkship Crash Course 3 April Walker, ‘85 The House Sweatt Built 4 February is dedicated to promoting the Carl Walker, Jr. '55 magnificent contributions that African Fad Wilson, Jr. ‘74 Poetry Contest 5 Americans have given to our society. Linda Renya Yanez, ‘76 ProDoc 5.1 6 The Law Library remembers the current Members of the legislatures that and former members of the judiciary that came from our ranks include: Let the Games Begin 7 came from the ranks of Thurgood Mar- Present & Former State Legislature Student Survey 8 shall School of Law. Archid L. Cofer, ‘74 Robert Lee Anderson, ‘70 Harold Dutton, ‘91 James Neal Barkley, ‘75 Antonio Garcia, ‘70 ton, Texas Weldon H. Berry, ‘52 James P.C. Hopkins,’67 Iris Jones, '77, first African Ameri- Calvin Botley, ‘72 Sam Hudson, ‘67 can and woman appointed City At- Beradelin L. Brashear, ‘67 Senfronia Thompson, ‘77 torney in Austin, Texas Durrey Edward Davis, ‘54 United States Legislature Raymond Jordan ‘62 Board of Ex- Henry Doyle, ‘50 Craig Washington, ‘69 aminers Bonnie Fitch, ‘74 Some other distinguished alumni that Donald Floyd, ‘72 came from our ranks include: Mark McDonald ‘62 first African Richard H. Garcia, ‘73 American appointed to the Board of John Crump, '70, Exe Director, NBA Sylvia Garcia, ‘91 Examiners & former President NBA. Harrison M. Gregg, Jr., ‘71 Al Green, President, NAACP, Hous- Ruben Guerrero, ‘76 Belinda Hill, '82 Kenneth Hoyt, ‘72 Carolyn Day Hobson, ‘70 Shirley Hunter, ‘76 Faith Simmons Johnson,'80 Mereda D. -

Faculty Guide 2021-2022

Faculty Administration JUDITH KELLEY: Dean, Sanford School of Public Policy; ITT/Terry Sanford Professor of Public Policy; Professor of Political Science, Bass Fellow PhD (Public Policy), Harvard University, 2001 Pronouns: She/her/hers Faculty Guide 2021-2022 Research: International relations and institutions; international law and norms; international election mon- itoring; democracy promotion; human rights; human This academic year, the Sanford School of trafficking; the role of external actors in domestic political reforms Public Policy celebrates 50 years since the CORINNE M. KRUPP: Associate Dean for Academic founding of the public policy program Programs; Professor of the Practice of Public Policy at Duke University in 1971. The Sanford PhD (Economics), University of Pennsylvania, 1990 Pronouns: She/her/hers School faculty have earned national and inter- Research: International trade policy; antidumping law national recognition for excellence in research, and firm behavior; competition policy; European Union policy engagement and teaching. The school has a diverse mix trade and finance issues; economic development of academic scholars and professors of the practice whose prac- PHILIP M. NAPOLI: Senior Associate Dean for tical experience in top leadership roles enhances the classroom Faculty and Research; James R. Shepley Professor of experience. Faculty members collaborate across disciplines to Public Policy; Director, DeWitt Wallace Center for explore questions relating to income inequality, obesity and Media & Democracy PhD (Mass -

Chapter Three Southern Business and Public Accommodations: an Economic-Historical Paradox

Chapter Three Southern Business and Public Accommodations: An Economic-Historical Paradox 2 With the aid of hindsight, the landmark Civil Rights legislation of 1964 and 1965, which shattered the system of racial segregation dating back to the nineteenth century in the southern states, is clearly identifiable as a positive stimulus to regional economic development. Although the South’s convergence toward national per capita income levels began earlier, any number of economic indicators – personal income, business investment, retail sales – show a positive acceleration from the mid 1960s onward, after a hiatus during the previous decade. Surveying the record, journalist Peter Applebome marveled at “the utterly unexpected way the Civil Rights revolution turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to the white South, paving the way for the region’s newfound prosperity.”1 But this observation poses a paradox for business and economic history. Normally we presume that business groups take political positions in order to promote their own economic interests, albeit at times shortsightedly. But here we have a case in which regional businesses and businessmen, with few exceptions, supported segregation and opposed state and national efforts at racial integration, a policy that subsequently emerged as “the best thing that ever happened to the white South.” In effect southern business had to be coerced by the federal government to act in its own economic self interest! Such a paradox in business behavior surely calls for explanation, yet the case has yet to be analyzed explicitly by business and economic historians. This chapter concentrates on public accommodations, a surprisingly neglected topic in Civil Rights history. -

Teacher's Guide

1 PARALLEL AND CROSSOVER LIVES: TEXAS BEFORE AND AFTER DESEGREGATION SECTION GOES HERE 1 Texas Council the for HUMANITIES presents PARALLEL AND CROSSOVER LIVES: Texas Before and After Segregation Welcome! This education package contains: Videotape Highlights two oral history interviews created through the Texas Council for the Humanities program, Parallel and Crossover Lives: Texas Before and After Desegregation. The video includes two separate oral history interview sessions: one conducted in Austin, Texas (approximately 25 minutes), the other in the small east Texas town of Hawkins (approximately 50 minutes). In these interviews, African-American and Anglo students, teachers, and school administrators describe the roles they played in the history of school desegregation in Texas. Introduction Dr. Glenn Linden, Dedman College Associate Professor of History, Southern Methodist University, and author of Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts. Teacher’s Guide prepared by Carol Schelnk Video discussion guide Classroom Extension Activities with links to related online URLS These activities were designed for use with high school students, but may be modified for middle school students. Vocabulary National and Texas state curriculum standards Educator feedback form Complete and returned to Texas Council for the Humanities Please visit our Parallel and Crossover Lives website at www.public-humanities.org/desegregation.html 2 PARALLEL AND CROSSOVER LIVES: TEXAS BEFORE AND AFTER DESEGREGATION INTRODUCTION 3 Introduction The Supreme Court’s momentous Brown vs. Board of Education decision mandating During the same years, the state of Texas wrestled with its response to the federal an end to “separate but equal” public education changed forever the entire fabric of demands for desegregation. -

Student Viewing Guide

YEZ yez OH YAY! Viewing Guide: Sweatt v. Painter (1950) The Background of the Case (00:00-2:25) 1. What did the Texas Constitution of 1876 say about segregation and separate but equal with regards to education? 2. What group had achieved some progress in the courts to end segregation in public schools? 3. At this time, what two leaders in the NAACP were determined to dismantle and end segregation? Stop and Think: Why do you think that the NAACP concentrated on ending segregation in public education? Heman Sweatt (2:26-6:10) 4. Who was Heman Sweatt and what did he do? Who was Theophilus Painter and what role did he play in the controversy? 5. What did the Texas Legislature do in response to Mr. Sweatt’s lawsuit? 6. Why did Mr. Sweatt continue his lawsuit against the University of Texas even after the Texas Legislature and the University of Texas had attempted to solve the issue? Stop and Think: Would you have been satisfied with the solution to the issue offered by the Texas Legislature and the University of Texas Law School? Why or why not? Question brought to the Supreme Court (6:11-7:39) 7. What was the question that the Supreme Court had to answer in this case? [Formula for issue=Yes/No question + facts of the case + part of the U.S. Constitution in question] © State Bar of Texas 8. What were the two arguments used by Sweatt’s attorneys in arguing the case? Stop and Think: What did the attorney mean when he said they hoped to “cut the roots out of segregation”? The Ruling (7:40-10:20) 9. -

Stadiums of Status: Civic Development, Race, and the Business of Sports in Atlanta, Georgia, 1966-2019

i Stadiums of Status: Civic Development, Race, and the Business of Sports in Atlanta, Georgia, 1966-2019 By Joseph Loughran Senior Honors Thesis History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill May 1, 2020 Approved: ___________________________________ Dr. Matthew Andrews, Thesis Advisor Dr. William Sturkey, Reader i Acknowledgements I could not have completed this thesis without the overwhelming support from my mother and father. Ever since I broached the idea of writing a thesis in spring 2019, they not only supported me, but guided me through the tough times in order to create this project. From bouncing ideas off you to using your encouragement to keep pushing forward, I cannot thank the both of you enough. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Matthew Andrews, for his constant support, guidance, and advice over the last year. Rather than simply giving feedback or instructions on different parts of my thesis, our meetings would turn into conversations, feeding off a mutual love for learning about how sports impact history. While Dr. Andrews was an advisor for this past year, he will be a friend for life. Thank you to Dr. Michelle King as well, as her guidance throughout the year as the teacher for our thesis class was invaluable. Thank you for putting up with our nonsense and shepherding us throughout this process, Dr. King. This project was supported by the Tom and Elizabeth Long Excellence Fund for Honors administered by Honors Carolina, as well as The Michel L. and Matthew L. Boyatt Award for Research in History administered by the Department of History at UNC-Chapel Hill. -

Racial Conflict Are U.S

Published by CQ Press, an Imprint of SAGE Publications, Inc. www.cqresearcher.com Racial Conflict Are U.S. policies discriminatory? ac e-centered conflicts in several U.S. cities have led to the strongest calls for policy reforms since the turbulent civil rights era of the 1960s. Propelled R largely by videos of violent police confrontations with African-Americans, protesters have taken to the streets in Chicago, New York and other cities demanding changes in police tactics. meanwhile, students — black and white — at several major universities have pressured school presidents to deal aggressively Demonstrators on Christmas Eve protest an alleged with racist incidents on campus. And activists in the emerging cover-up of a video showing a white Chicago police officer shooting 17-year-old African-American Laquan Black Lives matter movement are charging that “institutional racism” McDonald 16 times. The shooting — and others in which white police officers killed black suspects, often unarmed — has added fuel to a persists in public institutions and laws a half century after legally nationwide debate about systemic racism. sanctioned discrimination was banned. Critics of that view argue that moral failings in the black community — and not institutional racism — e xplain why many African-Americans lack parity with whites in such areas as wealth, employment, housing and educa - I tional attainment. B ut those who cite institutional racism say enor - THIS REPORT N THE ISSUES ......................27 mous socioeconomic gaps and entrenched housing and school S BACKGROUND ..................33 segregation patterns stem from societal decisions that far outweigh I CHRONOLOGY ..................35 individuals’ life choices. D CURRENT SITUATION ..........40 E CQ Researcher • Jan. -

Swinney, Wilford 03-31-1986 Transrcipt

Interview with Captain Wilford Swinney Interviewer: Kerry Owens Transcriber: Kerry Owens Date of Interview: March 31, 1986 Location: Austin Police Department, Austin, TX _____________________ Begin Tape 1, Side 1 Kerry Owens: This is Kerry Owens, and I’m doing an interview for Southwest Texas State University, the Oral History Project, in the History Department. This is March thirty-first. It’s 9:00. I’m at the Austin Police Department, and I’m interviewing Captain Wilford— Wilford Swinney: W-I-L-F-O-R-D and the last name is S-W-I-N-N-E-Y. Owens: Wilford Swinney. He’s been with the Austin Police Department for quite some time. Captain Swinney and I have discussed the legalities of the interview and the options he has available as far as editing, that type of thing. I don’t think at this point he has any questions. Do you think it’s pretty clear, Captain Swinney, as far as how we’re going to conduct the interview? Swinney: Yes, it’s clear now. Owens: I guess I’ll start the interview by asking Captain Swinney when he started to work for the Austin Police Department, or if he did something prior to that. Are you from Austin originally? Swinney: Well, I came here at the age of five. I was born in a place called Burnet County, and the nearest town at that time was Bertram. I was born about two miles south of Bertram, off of Highway 29, old Highway 29. It doesn’t exist any longer. The new Highway 20 goes through there now. -

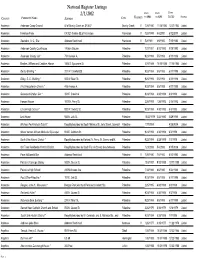

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE to SBR to NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE TO SBR TO NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY AndersonAnderson Camp Ground W of Brushy Creek on SR 837 Brushy Creek V7/25/1980 11/18/1982 12/27/1982 Listed AndersonFreeman Farm CR 323 3 miles SE of Frankston Frankston V7/24/1999 5/4/2000 6/12/2000 Listed AndersonSaunders, A. C., Site Address Restricted Frankston V5/2/1981 6/9/1982 7/15/1982 Listed AndersonAnderson County Courthouse 1 Public Square Palestine7/27/1991 8/12/1992 9/28/1992 Listed AndersonAnderson County Jail * 704 Avenue A. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonBroyles, William and Caroline, House 1305 S. Sycamore St. Palestine5/21/1988 10/10/1988 11/10/1988 Listed AndersonDenby Building * 201 W. Crawford St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonDilley, G. E., Building * 503 W. Main St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonFirst Presbyterian Church * 406 Avenue A Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonGatewood-Shelton Gin * 304 E. Crawford Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonHoward House 1011 N. Perry St. Palestine3/28/1992 1/26/1993 3/14/1993 Listed AndersonLincoln High School * 920 W. Swantz St. Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonLink House 925 N. Link St. Palestine10/23/1979 3/24/1980 5/29/1980 Listed AndersonMichaux Park Historic District * Roughly bounded by South Michaux St., Jolly Street, Crockett Palestine1/17/2004 4/28/2004 Listed AndersonMount Vernon African Methodist Episcopal 913 E. -

Uncovering the Case of Sweatt V. Painter and Its Legal Importance

History in the Making Volume 4 Article 6 2011 Whatever Means Necessary: Uncovering the Case of Sweatt v. Painter and Its Legal Importance Adam Scott Miller CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Recommended Citation Miller, Adam Scott (2011) "Whatever Means Necessary: Uncovering the Case of Sweatt v. Painter and Its Legal Importance," History in the Making: Vol. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol4/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Scott Miller Whatever Means Necessary: Uncovering the Case of Sweatt v Painter and Its Legal Importance BY ADAM SCOTT MILLER Abstract: The road to end segregation in the United States has been a long uphill battle for African Americans. The purpose of this paper serves several critical purposes. The first function is to educate the reader about the legal struggles that African Americans endured between the era of Reconstruction and the Supreme Court desegregating graduate school case of Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. Not only was this elusive case an important stepping stone in reversing the “Separate but Equal Doctrine” upheld by the Supreme Court in 1886, this case shows the lengths that segregationists went to in maintaining the status quo of racial separation. Finally, this paper will demonstrate the legal relevance that Sweatt v. -

The Eyes of Texas History Committee Report

The University of Texas at Austin The Eyes of Texas History Committee Report March 9, 2021 v3_03.10.2021 Table of Contents Letter to the President 1 Executive Summary 3 Charges 8-55 Charge 1: Collect and document the facts of: the origin, the creators’ intent, 8 and the elements of “The Eyes of Texas,” including the lyrics and music. Charge 2: Examine the university’s historical institutional use and 18 performance of “The Eyes of Texas." Charge 3: Chronicle the historical usage of “The Eyes of Texas” by University 18 of Texas students, staff, faculty and alumni, as well as its usage in broader cultural events, such as film, literature and popular media. Timeline of Milestones 50 Charge 4: Recommend potential communication tactics and/or 53 strategies to memorialize the history of “The Eyes of Texas." The Eyes of Texas History Committee Members 57 An Open Letter to President Hartzell and the University of Texas Community Dear President Hartzell and Members of the Longhorn Nation, With humility, we submit to you the product of our collective work, The Eyes of Texas History Committee Report. From the announcement of our committee on October 6, 2020, to late February, our collective endeavored to research, analyze, and collect data to respond to the four charges issued to us. Before acknowledging one of the most impactful, memorable and inspiring committees, I must first recognize that our work would not have been possible without the voice, courage and action of our students, especially our student-athletes. No words can express our committee’s pride in their love for our university as well as their deep desire to effect positive long-term change. -

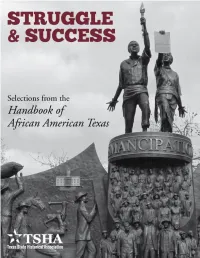

Struggle and Success Page I the Development of an Encyclopedia, Whether Digital Or Print, Is an Inherently Collaborative Process

Cover Image: The Texas African American History Memorial Monument located at the Texas State Capitol, Austin, Texas. Copyright © 2015 by Texas State Historical Association All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions,” at the address below. Texas State Historical Association 3001 Lake Austin Blvd. Suite 3.116 Austin, TX 78703 www.tshaonline.org IMAGE USE DISCLAIMER All copyrighted materials included within the Handbook of Texas Online are in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107 related to Copyright and “Fair Use” for Non-Profit educational institutions, which permits the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), to utilize copyrighted materials to further scholarship, education, and inform the public. The TSHA makes every effort to conform to the principles of fair use and to comply with copyright law. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Dear Texas History Community, Texas has a special place in history and in the minds of people throughout the world. Texas symbols such as the Alamo, oil wells, and even the shape of the state, as well as the men and women who worked on farms and ranches and who built cities convey a sense of independence, self-reliance, hard work, and courage.