Family of Heman Sweatt As Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marshall News Vol 3 Issue 3 Feb 2007

TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY VOLUME 3 ISSUE 3 Marshall News M ARCH 19, 2007 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Black History Month — Meet the Law Library 2 Staff Remembering Our Past Clerkship Crash Course 3 April Walker, ‘85 The House Sweatt Built 4 February is dedicated to promoting the Carl Walker, Jr. '55 magnificent contributions that African Fad Wilson, Jr. ‘74 Poetry Contest 5 Americans have given to our society. Linda Renya Yanez, ‘76 ProDoc 5.1 6 The Law Library remembers the current Members of the legislatures that and former members of the judiciary that came from our ranks include: Let the Games Begin 7 came from the ranks of Thurgood Mar- Present & Former State Legislature Student Survey 8 shall School of Law. Archid L. Cofer, ‘74 Robert Lee Anderson, ‘70 Harold Dutton, ‘91 James Neal Barkley, ‘75 Antonio Garcia, ‘70 ton, Texas Weldon H. Berry, ‘52 James P.C. Hopkins,’67 Iris Jones, '77, first African Ameri- Calvin Botley, ‘72 Sam Hudson, ‘67 can and woman appointed City At- Beradelin L. Brashear, ‘67 Senfronia Thompson, ‘77 torney in Austin, Texas Durrey Edward Davis, ‘54 United States Legislature Raymond Jordan ‘62 Board of Ex- Henry Doyle, ‘50 Craig Washington, ‘69 aminers Bonnie Fitch, ‘74 Some other distinguished alumni that Donald Floyd, ‘72 came from our ranks include: Mark McDonald ‘62 first African Richard H. Garcia, ‘73 American appointed to the Board of John Crump, '70, Exe Director, NBA Sylvia Garcia, ‘91 Examiners & former President NBA. Harrison M. Gregg, Jr., ‘71 Al Green, President, NAACP, Hous- Ruben Guerrero, ‘76 Belinda Hill, '82 Kenneth Hoyt, ‘72 Carolyn Day Hobson, ‘70 Shirley Hunter, ‘76 Faith Simmons Johnson,'80 Mereda D. -

Teacher's Guide

1 PARALLEL AND CROSSOVER LIVES: TEXAS BEFORE AND AFTER DESEGREGATION SECTION GOES HERE 1 Texas Council the for HUMANITIES presents PARALLEL AND CROSSOVER LIVES: Texas Before and After Segregation Welcome! This education package contains: Videotape Highlights two oral history interviews created through the Texas Council for the Humanities program, Parallel and Crossover Lives: Texas Before and After Desegregation. The video includes two separate oral history interview sessions: one conducted in Austin, Texas (approximately 25 minutes), the other in the small east Texas town of Hawkins (approximately 50 minutes). In these interviews, African-American and Anglo students, teachers, and school administrators describe the roles they played in the history of school desegregation in Texas. Introduction Dr. Glenn Linden, Dedman College Associate Professor of History, Southern Methodist University, and author of Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts. Teacher’s Guide prepared by Carol Schelnk Video discussion guide Classroom Extension Activities with links to related online URLS These activities were designed for use with high school students, but may be modified for middle school students. Vocabulary National and Texas state curriculum standards Educator feedback form Complete and returned to Texas Council for the Humanities Please visit our Parallel and Crossover Lives website at www.public-humanities.org/desegregation.html 2 PARALLEL AND CROSSOVER LIVES: TEXAS BEFORE AND AFTER DESEGREGATION INTRODUCTION 3 Introduction The Supreme Court’s momentous Brown vs. Board of Education decision mandating During the same years, the state of Texas wrestled with its response to the federal an end to “separate but equal” public education changed forever the entire fabric of demands for desegregation. -

Student Viewing Guide

YEZ yez OH YAY! Viewing Guide: Sweatt v. Painter (1950) The Background of the Case (00:00-2:25) 1. What did the Texas Constitution of 1876 say about segregation and separate but equal with regards to education? 2. What group had achieved some progress in the courts to end segregation in public schools? 3. At this time, what two leaders in the NAACP were determined to dismantle and end segregation? Stop and Think: Why do you think that the NAACP concentrated on ending segregation in public education? Heman Sweatt (2:26-6:10) 4. Who was Heman Sweatt and what did he do? Who was Theophilus Painter and what role did he play in the controversy? 5. What did the Texas Legislature do in response to Mr. Sweatt’s lawsuit? 6. Why did Mr. Sweatt continue his lawsuit against the University of Texas even after the Texas Legislature and the University of Texas had attempted to solve the issue? Stop and Think: Would you have been satisfied with the solution to the issue offered by the Texas Legislature and the University of Texas Law School? Why or why not? Question brought to the Supreme Court (6:11-7:39) 7. What was the question that the Supreme Court had to answer in this case? [Formula for issue=Yes/No question + facts of the case + part of the U.S. Constitution in question] © State Bar of Texas 8. What were the two arguments used by Sweatt’s attorneys in arguing the case? Stop and Think: What did the attorney mean when he said they hoped to “cut the roots out of segregation”? The Ruling (7:40-10:20) 9. -

Uncovering the Case of Sweatt V. Painter and Its Legal Importance

History in the Making Volume 4 Article 6 2011 Whatever Means Necessary: Uncovering the Case of Sweatt v. Painter and Its Legal Importance Adam Scott Miller CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Recommended Citation Miller, Adam Scott (2011) "Whatever Means Necessary: Uncovering the Case of Sweatt v. Painter and Its Legal Importance," History in the Making: Vol. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol4/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Scott Miller Whatever Means Necessary: Uncovering the Case of Sweatt v Painter and Its Legal Importance BY ADAM SCOTT MILLER Abstract: The road to end segregation in the United States has been a long uphill battle for African Americans. The purpose of this paper serves several critical purposes. The first function is to educate the reader about the legal struggles that African Americans endured between the era of Reconstruction and the Supreme Court desegregating graduate school case of Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. Not only was this elusive case an important stepping stone in reversing the “Separate but Equal Doctrine” upheld by the Supreme Court in 1886, this case shows the lengths that segregationists went to in maintaining the status quo of racial separation. Finally, this paper will demonstrate the legal relevance that Sweatt v. -

Struggle and Success Page I the Development of an Encyclopedia, Whether Digital Or Print, Is an Inherently Collaborative Process

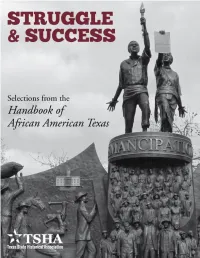

Cover Image: The Texas African American History Memorial Monument located at the Texas State Capitol, Austin, Texas. Copyright © 2015 by Texas State Historical Association All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions,” at the address below. Texas State Historical Association 3001 Lake Austin Blvd. Suite 3.116 Austin, TX 78703 www.tshaonline.org IMAGE USE DISCLAIMER All copyrighted materials included within the Handbook of Texas Online are in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107 related to Copyright and “Fair Use” for Non-Profit educational institutions, which permits the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), to utilize copyrighted materials to further scholarship, education, and inform the public. The TSHA makes every effort to conform to the principles of fair use and to comply with copyright law. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. Dear Texas History Community, Texas has a special place in history and in the minds of people throughout the world. Texas symbols such as the Alamo, oil wells, and even the shape of the state, as well as the men and women who worked on farms and ranches and who built cities convey a sense of independence, self-reliance, hard work, and courage. -

Annotated Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES “The 13th Street Law School.” Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice, University of Texas Press, 2010. This is an image of “the basement school” as referred to by Thurgood Marshall. The school was established to satisfy the order of Judge Archer, who later found the school to be “substantially equal” to the University of Texas Law School. “African American Woman Hard at Work” Venable, Rose. The Civil Rights Movement: Journey to Freedom. Childs World, 2010. This photo shows a black woman working very hard for little to no pay. Even after slavery was abolished, African-Americans were not treated equally or fairly, and they were not accepted as the free citizens they were supposed to be. One cause of this was the Jim Crow Laws, which would have an impact on our nation for many years. “Appeal Filed in Sweatt Case.” The Kilgore News Herald, 30 Sept. 1947, pp. 1–1. This newspaper article was written about Heman Sweatt’s appeal to the Third Court of Civil Appeals. The publicity that Heman Sweatt received made him a hero to other African-Americans but a villain to those fighting against integration and equalization. Benoit, Reese, and Dale Wainwright. “Interview with Former Texas Supreme Court Justice Dale Wainwright.” 10 Mar. 2020. Dale Wainwright is a former Texas Supreme Court Justice. Justice Wainwright participated in a moot argument of Sweatt v. Painter in which he argued the case on behalf of Heman Sweatt, just as Thurgood Marshall did. In preparation, he thoroughly researched the Sweatt case, and the knowledge he shared greatly benefited my project. -

Panther Newspapers Publications

Prairie View A&M University Digital Commons @PVAMU PV Panther Newspapers Publications 2-1947 Panther - February 1947 - Vol. XXI No. 3 Prairie View University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers Recommended Citation Prairie View University. (1947). Panther - February 1947 - Vol. XXI No. 3., Vol. XXI No. 3 Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers/808 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @PVAMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in PV Panther Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @PVAMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOPHOMORE ISSUE VOLUME 21 PRAIRIE VIEW UNIVERSITY, PRAIRIE VIEW BRANCH, HE MPSTEAD, TEXAS, FEBRUARY, 1947 NUMBER 3 PROMINENT ALUMNUS MAKES GIFT TO PRAIRIE VIEW MISS LILLIAN BROWN CROWNED AT GALA PANTHER CORONATION BALL The crowning of Miss Lillian quets of red roses. The princes Marie Brown was the prevailing were formally attired. The flower feature of the fifteenth annual girls were daintily gowned in sheer Coronation Ball sponsored Satur net, miniature princess-like dresses day evening, January 25 in the and carried baskets of rose petals University Auditorium by the which were strewn along the line Panther executive staff of Prairie of the procession as a signal for View. Miss Brown, the daughter the queens's appearance. The of Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Brown of Crown-bearer was regally clothed Houston, Texas, was deemed "Miss in a rich white suit. Prairie View" for 1946-47 in Octo The beautiful bronze queen made ber 1946, when she was declared her stately entrance as the organ winner of the "Miss Prairie View" ist played soft strains of the Cor drive. -

Sweatt Family Amicus Brief in Fisher V. University of Texas

NO. 11-345 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ ABIGAIL NOEL FISHER, Petitioner, v. UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, et al., Respondents. ________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT ________________ BRIEF OF THE FAMILY OF HEMAN SWEATT AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS _______________ Allan Van Fleet Counsel of Record Nicholas Grimmer McDermott Will & Emery LLP 1000 Louisiana, Suite 3900 Houston, Texas 77002-5005 (713) 653-1703 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Hemella Sweatt-Duplechan, M.D. James Leonard Sweatt III, M.D. Heman Marion Sweatt II i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 5 I. SWEATT V. PAINTER ..................................... 5 A. Sweatt’s Application and Painter’s Response ................................ 5 B. Sweatt’s Many Dimensions ................... 8 C. Sweatt’s Suit and the “Basement School” .................................................. 10 D. The Trial of Intangibles and the Interplay of Ideas ................................. 13 E. This Court’s Opinions of June 5, 1950 ...................................................... 16 II. SWEATT’S LIFE AND LEGACY AFTER SWEATT V. PAINTER ..................... 19 A. Sweatt at UT ....................................... -

Sweatt V. Painter Author(S): Thomas Clarkin Source: Encyclopedia of Civil Rights in America

Title: Sweatt v. Painter Author(s): Thomas Clarkin Source: Encyclopedia of Civil Rights in America. Ed. David Bradley and Shelley Fisher Fishkin. Vol. 3. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 1998. p841-842. Document Type: Topic overview Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1998 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Page 841 Sweatt v. Painter 1950: U.S. SUPREME COURT decision regarding the SEPARATE-BUT-EQUAL PRINCIPLE in COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY EDUCATION. In early 1946 Heman Marion Sweatt, an African American postman, applied to the University of Texas School of Law. Although Sweatt already possessed both a bachelor's degree from Wiley College and credit for graduate work he had completed at the University of Michigan, he was denied admission to the law school because of his race. Sweatt then filed a lawsuit in state court against the university, charging that rejection of his application on the basis of race violated his Fourteenth Amendment right to EQUAL PROTECTION under the law. A state judge ruled that the university must either admit Sweatt or establish a law school for African Americans that would offer training equivalent to that of the law school at the University of Texas. However, when the state created a law school for blacks in Houston, Sweatt refused to enrol in it and again filed a lawsuit. The Texas courts offered Sweatt no relief, and in March, 1949, his case came before the U.S. SUPREME COURT. Thurgood MARSHALL, an attorney for the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP), hoped that Sweatt's case would overturn the Court's 1896 decision in PLESSY V. -

Packet of 1St Place Essays

A New Beginning A New Beginning The judicial system in America is flawed and often times inaccurate, resulting in the discrediting of someone’s reputation and the removal of their freedom. In Texas history, we have known this to be particularly relevant to the African American community due to the history of racism and segregation in the South. Barbara Jordan demanded change when she reached incredible heights and made Texas history as she became the first African American woman to be elected to the State Senate and further down the road in her political career, the first African American woman from the south to become a representative in the United States House of Representatives. Jordan pushed for justice during the civil rights era and left a legacy behind her. Her accomplishments were so graceful they seemed effortless, as she faced adversity due to the color of her skin. “The character, certainty, and command at the core of Barbara Jordan, the powerful woman whose voice could move men and women to tears, insight, inspiration, or action, came from that blackness and from her acceptance of it. She took pride in her own inner power.” (Rogers, 5). With the acceptance of who she was, she was able to realize the amount of strength and power that ran through her DNA. She chose to silence the stereotypes of the world telling her she couldn’t because she didn’t look like the current politicians in office. Yes, she not only silenced the 1 world’s negativity, but also won the world over using nothing but optimism, intelligence, and hard work. -

Brief on the Merits of Respondent for Fisher V. University of Texas at Austin

No. 11-345 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ABIGAIL NOEL FISHER, Petitioner, v. UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, et al., Respondents. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT BRIEF OF THE ADVANCEMENT PROJECT AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS AND URGING AFFIRMANCE TOMIKO BROWN-NAGIN Counsel of Record HARVARD LAW SCHOOL 1585 MASSACHUSETTS AVE. CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138 (617) 384-5982 [email protected] LANI GUINIER HARVARD LAW SCHOOL 1585 MASSACHUSETTS AVE. CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138 Counsel for Amicus Curiae The Advancement Project i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 3 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 8 I. UT’S CURRENT ADMISSIONS POLICY REFLECTS THE EVOLUTION OF THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THE UNIVERSITY ITSELF FROM A CLOSED, RACIALLY- EXCLUSIONARY SOCIETY TO A MORE OPEN SOCIETY WHERE THE UNIVERSITY VALUES A MULTIRACIAL CITIZENRY ........................... 8 A. UT Excluded Applicants Solely on Account of Race for Most of Its History .................................................. 12 B. UT and the State of Texas Enforced Segregation and Punished Integrationists Well After Sweatt v. Painter .................................................. 15 C. UT’s Chilly Racial Climate in Recent Years ..................................................... 20 D. UT’s Current Admissions Policy Helps to Redeem its History and to Remedy Vestiges of Segregation -

Brief of Respondent for Fisher V. University of Texas at Austin; 11-345

NO. 11-345 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ ABIGAIL NOEL FISHER, Petitioner, v. UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, et al., Respondents. ________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT ________________ BRIEF OF THE FAMILY OF HEMAN SWEATT AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS _______________ Allan Van Fleet Counsel of Record Nicholas Grimmer McDermott Will & Emery LLP 1000 Louisiana, Suite 3900 Houston, Texas 77002-5005 (713) 653-1703 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Hemella Sweatt-Duplechan, M.D. James Leonard Sweatt III, M.D. Heman Marion Sweatt II i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 5 I. SWEATT V. PAINTER ..................................... 5 A. Sweatt’s Application and Painter’s Response ................................ 5 B. Sweatt’s Many Dimensions ................... 8 C. Sweatt’s Suit and the “Basement School” .................................................. 10 D. The Trial of Intangibles and the Interplay of Ideas ................................. 13 E. This Court’s Opinions of June 5, 1950 ...................................................... 16 II. SWEATT’S LIFE AND LEGACY AFTER SWEATT V. PAINTER ..................... 19 A. Sweatt at UT .......................................