Patterns of Spanish Emigration to the New World (1493-1580). Special

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pilgrimage Brochure

Dear Friends, May 20, 2021 marks the 500 th anniversary of Ignatius de Loyola’s en- counter with a cannonball on the battlefield of Pam- plona, an event that brought with it a near- death experience and a lifelong adventure of con- version. The changes set in motion dramatically changed his direction and DAY-BY-DAY ITINERARY have reverberated down the centuries for the Church and the whole world. LOS ANGELES/ACROSS THE ATLANTIC FRIDAY, MAY 13 Ignatius fell in love with the God who Depart today from Los Angeles aboard your transatlantic saves him and pledged to follow Christ whom jet flight for Madrid, arriving the following day. he personally came to know, love, and follow more nearly day by day. This gritty human ARRIVE MADRID SATURDAY, MAY 14 being ardently desired to share his life- Your exciting adventure begins as you arrive today in Ma- altering experiences of God’s mercy and love drid. Free time to rest or explore the Spanish capital. (D) with others, and he sought to disseminate one of the more powerful forms of spirituality MADRID whose promise seems more relevant now than SUNDAY, MAY 15 ever. This morning on a tour of Madrid, see the white-trimmed 2,800-room Royal Palace and the exquisite gardens that This thoughtfully designed, ten-day pil- surround it. Other highlights include the Puerta del Sol, grimage offers you the opportunity to Cervantes Memorial, the Plaza de Espana and the acacia- strengthen your faith, come to know Jesus lined Castellana. Then visit the Prado Museum, housing a more deeply, and discover how the Holy Spir- collection of masterpieces by Spain's artists Velazquez, Goya and El Greco. -

How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

HOW CAN A MODERN HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY MAKE SENSE? ON NATION, IDENTITY, AND TERRITORIES IN THE MAKING OF SPAIN JOSE M. PORTILLO VALDES Universidad del Pais Vasco Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada (Reno) One of the more recurrent debates among Basque historians has to do with the very object of their primary concern. Since a Basque political body, real or imagined, has never existed before the end of the nineteenth century -and formally not until 1936- an «essentialist» question has permanently been hanging around the mind of any Basque historian: she might be writing the histo- ry of an non-existent subject. On the other hand, the heaviness of the «national dispute» between Basque and Spanish identities in the Spanish Basque territories has deeply determined the mean- ing of such a cardinal question. Denying the «other's» historicity is a very well known weapon in the hands of any nationalist dis- course and, conversely, claiming to have a millenary past behind one's shoulders, or being the bearer of a single people's history, is a must for any «national» history. Consequently, for those who consider the Spanish one as the true national identity and the Basque one just a secondary «decoration», the history of the Basque Country simply does not exist or it refers to the last six decades. On the other hand, for those Basques who deem the Spanish an imposed identity, Basque history is a sacred territory, the last refuge for the true identity. Although apparently uncontaminated by politics, Basque aca- demic historiography gently reproduces discourses based on na- - 53 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA tionalist assumptions. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution Map 0.1

CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Preface and Acknowledgments xiii Introduction Ana Varela-COPYRIGHTED Lago and Phylis Cancilla MATERIAL Martinelli 3 1. Working in AmericaNOT and FORLiving in DISTRIBUTIONSpain: The Making of Transnational Communities among Spanish Immigrants in the United States Ana Varela- Lago 21 2. The Andalucía- Hawaii- California Migration: A Study in Macrostructure and Microhistory Beverly Lozano 66 3. Spanish Anarchism in Tampa, Florida, 1886– 1931 Gary R. Mormino and George E. Pozzetta† 91 viii CONTENTS 4. “Yours for the Revolution”: Cigar Makers, Anarchists, and Brooklyn’s Spanish Colony, 1878– 1925 Christopher J. Castañeda 129 5. Pageants, Popularity Contests, and Spanish Identities in 1920s New York Brian D. Bunk 175 6. Miners from Spain to Arizona Copper Camps, 1880– 1930 Phylis Cancilla Martinelli 206 7. From the Mountains and Plains of Spain to the Hills and Hollers of West Virginia: Spanish Immigration into Southern West Virginia in the Early Twentieth Century Thomas Hidalgo 246 8. “Spanish Hands for the American Head?”: Spanish Migration to the United States and the Spanish State Ana Varela- Lago 285 Postscript. Hidden No Longer: Spanish Migration and the Spanish Presence in the United States Ana Varela- Lago and Phylis Cancilla Martinelli 320 List of Contributors 329 Index 333 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION MAP 0.1. Map of Spain COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION INTRODUCTION Ana Varela- Lago and Phylis Cancilla Martinelli In his book Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States, -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

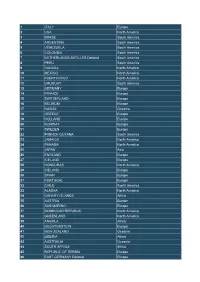

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century

BYU Family Historian Volume 1 Article 5 9-1-2002 Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century George R. Ryskamp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 1 (Fall 2002) p.14-22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Spanish Censuses of the Sixteenth Century by George R. Ryskamp, J.D., AG A genealogist tracing family lines backwards This article will be organized under a combination of in Spain will almost certainly find a lack of records the first and second approach, looking both at the that have sustained his research as he reaches the year nature of the original order to take the census and 1600. Most significantly, sacramental records in where it may be found, and identifying the type of about half ofthe parishes begin in or around the year census to be expected and the detail of its content. 1600, likely reflecting near universal acceptance and application of the order for the creation of baptismal Crown Censuses and marriage records contained in the decrees of the The Kings ofCastile ordered several censuses Council of Trent issued in 1563. 1 Depending upon taken during the years 1500 to 1599. Some survive the diocese between ten and thirty percent of only in statistical summaries; others in complete lists. 5 parishes have records that appear to have been In each case a royal decree ordered that local officials written in response to earlier reforms such as a (usually the municipal alcalde or the parish priest) similar decrees from the Synod of Toledo in 1497. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Ated in Specific Areas of Spain and Measures to Control The

No L 352/ 112 Official Journal of the European Communities 31 . 12. 94 COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 1994 derogating from prohibitions relating to African swine fever for certain areas in Spain and repealing Council Decision 89/21/EEC (94/887/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, contamination or recontamination of pig holdings situ ated in specific areas of Spain and measures to control the movement of pigs and pigmeat from special areas ; like Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European wise it is necessary to recognize the measures put in place Community, by the Spanish authorities ; Having regard to Council Directive 64/432/EEC of 26 June 1964 on animal health problems affecting intra Community trade in bovine animals and swine (') as last Whereas it is the objective within the eradication amended by Directive 94/42/EC (2) ; and in particular programme adopted by Commission Decision 94/879/EC Article 9a thereof, of 21 December 1994 approving the programme for the eradication and surveillance of African swine fever presented by Spain and fixing the level of the Commu Having regard to Council Directive 72/461 /EEC of 12 nity financial contribution (9) to eliminate African swine December 1972 on animal health problems affecting fever from the remaining infected areas of Spain ; intra-Community trade in fresh meat (3) as last amended by Directive 92/ 1 18/EEC (4) and in particular Article 8a thereof, Whereas a semi-extensive pig husbandry system is used in certain parts of Spain and named 'montanera' ; whereas -

Anejo Nº 3. Geología, Geotecnia Y Procedencia De Materiales

ANEJO Nº 3. GEOLOGÍA, GEOTECNIA Y PROCEDENCIA DE MATERIALES ANEJO Nº 3. GEOLOGÍA, GEOTECNIA Y PROCEDENCIA DE MATERIALES “Proyecto de Construcción. Construcción de glorietas en enlace tipo diamante. Autovía A-49, p.k. 117,100. Tramo: Enlace Huelva Norte – Enlace Lepe Oeste. Provincia de Huelva. Clave: 39-H-3880” PÁG. 1 ANEJO Nº 3. GEOLOGÍA, GEOTECNIA Y PROCEDENCIA DE MATERIALES ÍNDICE 3.- ANEJO Nº3. GEOLOGÍA, GEOTECNIA Y PROCEDENCIA DE MATERIALES .. 3 3.1.- INTRODUCCIÓN ....................................................................... 3 3.2.- GEOLOGÍA DE LA ZONA ............................................................ 3 3.2.1.- Estratigrafía............................................................... 6 3.2.2.- Tectónica .................................................................. 6 3.2.3.- Sismicidad................................................................. 8 3.3.- ESTUDIO DE MATERIALES ......................................................... 8 3.4.- GEOTECNIA ........................................................................... 10 APÉNDICE 1. CERTIFICADOS CONFORMIDAD CANTERA GEASUR .................... 11 APÉNDICE 2. ENSAYOS DE SUELOS CANTERA ALMENARA ............................. 16 “Proyecto de Construcción. Construcción de glorietas en enlace tipo diamante. Autovía A-49, p.k. 117,100. Tramo: Enlace Huelva Norte – Enlace Lepe Oeste. Provincia de Huelva. Clave: 39-H-3880” PÁG. 2 ANEJO Nº 3. GEOLOGÍA, GEOTECNIA Y PROCEDENCIA DE MATERIALES 3.- ANEJO Nº3. GEOLOGÍA, GEOTECNIA Y PROCEDENCIA DE MATERIALES En -

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1 Louisiana Historical Background 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 •Spain sides with France in the now expanded Seven Years War •The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which France ceded Louisiana (New France) to Spain. •Spain acquires Louisiana Territory from France 1763 •No troops or officials for several years •The colonists in western Louisiana did not accept the transition, and expelled the first Spanish governor in the Rebellion of 1768. Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion and formally raised the Spanish flag in 1769. Antonio de Ulloa Alejandro O'Reilly 1763 – 1770 1763 – 1770 •France’s secret treaty contained provisions to acquire the western Louisiana from Spain in the future. •Spain didn’t really have much interest since there wasn’t any precious metal compared to the rest of the South America and Louisiana was a financial burden to the French for so long. •British obtains all of Florida, including areas north of Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas and Bayou Manchac. •British built star-shaped sixgun fort, built in 1764, to guard the northern side of Bayou Manchac. •Bayou Manchac was an alternate route to Baton Rouge from the Gulf bypassing French controlled New Orleans. •After Britain acquired eastern Louisiana, by 1770, Spain became weary of the British encroaching upon it’s new territory west of the Mississippi. •Spain needed a way to populate it’s new territory and defend it. •Since Spain was allied with France, and because of the Treaty of Allegiance in 1778, Spain found itself allied with the Americans during their independence. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

Registro Vias Pecuarias Provincia Sevilla

COD_VP N O M B R E DE LA V. P. TRAMO PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO ESTADO LEGAL ANCHO LONGITUD PRIORIDAD USO PUBLICO 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_01 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 10 3 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_03 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 1629 3 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_02 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 2121 3 41001002 VEREDA DE OSUNA A ESTEPA 41001002_06 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 586 3 41001002 VEREDA DE OSUNA A ESTEPA 41001002_05 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 71 3 VEREDA DE SIERRA DE YEGÜAS O DE LA 41001003 PLATA 41001003_02 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 954 3 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_04 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 224 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_06 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 3244 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_07 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 57 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_08 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 17 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_05 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 734 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_01 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 1263 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_03 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 3021 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_02 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 428 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_09 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 2807 1 CAÑADA REAL DE CONSTANTINA Y DESLINDE 41002002 CAZALLA 41002002_02 SEVILLA