Dirty Old Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dirty Old Town C – 1949 Ewan Maccoll 4/4 C / / / / / F I Met My Love by the Gas Works Wall

Dirty Old Town C – 1949 Ewan MacColl 4/4 C / / / / / F I met my love by the gas works wall. Dreamed a dream / C / / / / by the old canal. I kissed my girl by the factory wall. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / F / Clouds are drifting across the moon. Cats are prowling on their C / / / / feet. Spring's a girl from the streets at night. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / F / I heard a siren from the docks. Saw a train set the night on C / / / / fire. I smelled the spring on the smoky wind. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / F / I'm gonna make me a good sharp axe. Shining steel tempered C / / / / in the fire. I'll chop you down like an old dead tree. C G / Am / Dirty old town, dirty old town. C / / / / F I met my love by the gas works wall. Dreamed a dream / C / / / / by the old canal. I kissed my girl by the factory wall. C G / Am / ||: Dirty old town, dirty old town. :|| repeat and fade Written about Salford, Lancashire, England where MacColl grew up. Popular version by the Pogues and the Dubliners. 3/13/2021 Dirty Old Town G – 1949 Ewan MacColl 4/4 G / / / / / C I met my love by the gas works wall. Dreamed a dream / G / / / / by the old canal. I kissed my girl by the factory wall. G D / Em / Dirty old town, dirty old town. G / / / C / Clouds are drifting across the moon. -

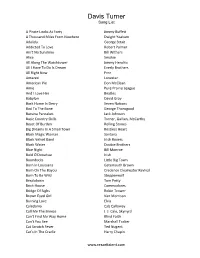

Davis Turner Song List

Davis Turner Song List A Pirate Looks At Forty Jimmy Buffett A Thousand Miles From Nowhere Dwight Yoakum Adalida George Strait Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Alice Smokie All Along The Watchtower Jimmy Hendrix All I Have To Do Is Dream Everly Brothers All Right Now Free Amazed Lonestar American Pie Don McClean Amie Pure Prairie League And I Love Her Beatles Babylon David Gray Back Home In Derry Seven Nations Bad To The Bone George Thorogood Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Basic Country Skills Turner, Gallian, McCarthy Beast Of Burden Rolling Stones Big Dreams In A Small Town Restless Heart Black Magic Woman Santana Black Velvet Band Irish Rovers Black Water Doobie Brothers Blue Night Bill Monroe Bold O'Donahue Irish Boondocks Little Big Town Born In Louisiana Gatemouth Brown Born On The Bayou Credence Clearwater Revival Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf Breakdown Tom Petty Brick House Commodores Bridge Of Sighs Robin Trower Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Burning Love Elvis Caledonia Cab Calloway Call Me The Breeze J. J. Cale, Skynyrd Can't Find My Way Home Blind Faith Can't You See Marshall Tucker Cat Scratch Fever Ted Nugent Cat's In The Cradle Harry Chapin www.resorttalent.com Charlie On The MTA Kingston Trio Chicken Fried Zack Brown China Grove Doobie Brothers City Of New Orleans Arlo Guthrie Cocaine J. J. Cale, Eric Clapton Cold Shot Stevie Ray Vaughn Come Monday Jimmy Buffett Come Out Ye Black And Tans Irish Cool Change Little River Band Copper Head Road Steve Earl Couldn't Stand The Weather Stevie Ray Vaughn -

THE CEILI FAMILY English

The Ceili Family is on tour-a-loo since 1996. Played small Pubs and Dive bars as well as well-known Open Air-Festivals...especially all over Germany! The band crossovers a lot. Irish Folk Festivals, Village Fairs or other occasions. Meets purist legends like the Dubliners, infamous Shane MacGowan or harlequins like German artist „Honigdieb“ and loads of great blokes of the Irish Folk (Punk) scene: Mr Irish Bastard, Celtica, Lady Godiva, Jamie Clarke’s Perfect, Paul McKenna Band, The Porters, Kings and Boozers, The O’Reillys and the Paddyhats, The Shanes, Across the Border, In search of the rose and many more. Size does not matter when it come to audiences. The Ceili Family does not care if they’re playing in front of a festival crowd of 2000 people or merely 50 drunks in a smokey Pub. The band is always playing their hearts out. Presenting their own songs. And classics like „Whiskey in the jar“ or „Dirty Old Town“ from time to time as well as trash-talking breaking out in laughter... The Ceili Family celebrates every concert as if it was the last. Or their first... And they have royal friends! On Tory Island! There’s not a single tree there... There’s not even a rat... But there is...a King!! Patsy Dan on duty. Welcoming everyone who comes to Tory Island. And wishing a fond farewell when Tory Ferry leaves again. And there’s always a session going on. And many a song to be sung in Tory’s Hotel bar... Check out The Ceili Family’s latest CD! Nine songs written by themselves. -

Development,Environmental Management and Taranaki

DEVELOPMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND TARANAKI his thesis explores how Māori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand, engage in environmental management processes in Taranaki in the context of postcolonial iwi [tribal] 1 development and negotiated settlements with the T government. Situating collaborative relationships in environmental management within the wider context of iwi development and postcolonial reconciliation reveals the complex interweaving of tensions, limitations and optimism that characterises this historical moment. Although ideas of settlement, reconciliation, partnership and collaboration invoke fixed and stable arrangements between Indigenous and government organisations, postcolonial coexistence is an ongoing process and remains profoundly unsettled. Drawing on postdevelopment and postcolonial theories I argue that (Indigenous) negotiations of collaborative environmental management and development can be read as unsettling openings that clear space for postcolonial mutuality and plurality. Government-led environmental management is a fundamentally cultural, spatial and political act that asserts and maintains the government’s prerogative to control the use and construction of places. Colonial appropriations of Indigenous land are stabilised 1 Throughout the thesis Maori words will be italicised and translated into English at their first usage. Maori words and their translations can also be found in the glossary. 1 CHAPTER ONE: Development, Environmental Management and Taranaki through the state’s environmental management; -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

ECM 8199942 V1 SUB18/47061

From: Hamish Crimp Sent: 18 Dec 2019 14:57:01 +1300 To: applications Subject: Seaport (Cool Stores) Subdivision and Land Use Resource Consent Application - Heritage Taranaki Submission Attachments: Heritage Taranaki Submission (submission form) for Seaport (Cool Stores) Subdivision and Land Use Resource Consent Application .pdf, Heritage Taranaki Submission (attached information) for Seaport (Cool Stores) Subdivision and Land Use Resource Consent Application.pdf Kia ora, Please find attached the two documents comprising Heritage Taranaki's submission on the Seaport (Cool Stores) Subdivision and Land Use Resource Consent Application. Please direct any queries regarding this submission to Hamish Crimp at [email protected]. Kind regards, Hamish Crimp, On behalf of Heritage Taranaki Incorporated Document Set ID: 8199942 Version: 1, Version Date: 18/12/2019 FORM 13 Submission on a resource consent application subject to public or limited notification Resource Management Act 1991 Submissions must be received by the end of the 20th working Email to: [email protected] day following the date the application was notified. Or post to: The Planning Lead If the application is subject to limited notification, New Plymouth New Plymouth District Council District Council may adopt an earlier closing date for submissions Private Bag 2025 once the Council receives responses from all affected parties. New Plymouth 4342 1. Submitter details 1a. Full name First name(s) Surname 1b. Contact person’s name if different from above e.g. lawyer, planner, First name(s) Surname surveyor Designation Company 1c. Electronic service address 1d. Telephone Mobile Landline 1e. Postal address or alternative method of service under Section 352 of RMA 1991 Serving of documents The Council will serve all formal documents electronically via the email address provided above. -

Michael Blake Setlist

MICHAEL BLAKE SETLIST Here is a list of most the songs Michael knows and can play live. This list is not everything, so feel free to reach out and check on a song if you have a special one in mind. He may already know it or be willing to learn it. We do charge a $50 song fee for the time spent learning a new song. Pop/Rock/Folk/Jazz: 1234 Feist A Long December Counting Crows A Warning Sign Coldplay A Sunday Kind of Love Etta James A Thousand Years Christina Perri (Twilight Soundtrack) All of Me John Legend All of Me Billie Holiday All I Want Is You Barry Louis Polisar (Juno Soundtrack) All I Want Is You U2 All This Time Sting All You Need Is Love – The Beatles Always On My Mind Willie Nelson Amy Ryan Adams And I Love Her The Beatles And It Stoned Me – Van Morrison Another Sunday Night – Sam Cooke, Cat Stevens At Last Etta James Babylon David Gray Bad Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Bad Blood Taylor Swift Between The Bars Elliot Smith Blackbird The Beatles Blue The Jayhawks Brighter Than Sunshine Aqualung Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison By Your Side Sade Can’t Keep It In Cat Stevens Calico Skies Paul McCartney Carolina In My Mind James Taylor Come Away With Me Norah Jones Come Pick Me Up Ryan Adams Coming Home Leon Bridges Country Comfort Elton John Country Roads – John Denver Crazy Love Van Morrison Don’t Dream It’s Over Crowded House Don't Know Why Norah Jones Don't Think Twice It's All Right Bob Dylan Easy Like Sunday Morning Lionel Ritchie/Commodores Emmylou - First Aid Kit Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic The Police Fade Into You Mazzy -

The Mostly Celtic Songbook

The Mostly Celtic Songbook Mostly Celtic Songbook 2 Introduction After sitting in on some of the former Tuesday evening open seisiúns at C.B. Hannegan’s in Los Gatos, and trying to sing along but not remembering the lyrics, it seemed like a good idea to compile a songbook that we could all potentially share. After one or two pints and a few encouraging words from Tony Becker, the idea became a project. So, here it is. In retrospect, it turned out to be more helpful to me than to the group, as most continued to use their own song collections. But at least I got most of the more frequently played songs together in one handy document, in keys that I can actually sing (the “suggested key”). It was well worth the effort, and a great way to learn the songs. In some cases, I took the liberty of editing some of the traditional lyrics for readability and sing-ability, especially the lyrics I got from the Web, and adding or changing a few chords, since many of the songs exist in several different versions anyway. Thanks to YouTube, I was able to correct a lot of mistakes. Some of the songs are still under copyright protection, so if I’ve given a wrong attribution, please send me a note so I can correct the error. A thousand apologies if that is the case. This book is intended for private use only, not for commercial publication. The chords are written in Nashville notation (well, sort of), so transposing is simple. -

The Best of the Pogues Free

FREE THE BEST OF THE POGUES PDF Music Sales Corporation | 63 pages | 08 Oct 1991 | Music Sales Ltd | 9780711929029 | English | London, United Kingdom The Best of the Pogues - The Pogues | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic More The Best of the Pogues. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Master Release. Folk Rock. James Fearnley Accordion, Piano. Jem Finer Banjo, Saxophone. Darryl Hunt Bass, Vocals. Terry Woods Cittern, Vocals. William Wegman Cover. Paul McGuinness Crew. Dave Jordan Crew. Paul Scully Crew. Charlie MacLennan Crew. Charlie Malcolm Crew. Paul Verner Crew, Lighting. Joey Cashman Crew, Management. Ryan Art Design. Andrew Ranken Drums, Vocals. Philip Chevron Guitar, Vocals. Iain McKell Photography By. Elvis Costello Producer. Steve Lillywhite Producer. John Minihan Sleeve. Spider Stacy Tin Whistle, Vocals. Purchased today and overall it's disappointing. I knew instantly something was afoot when I was having to turn the amp up to levels not normally used, just to get some decent volume. It lacks clout and verve to say the least. To give it its The Best of the Pogues it does sound clean and polished - possibly compressed or more digital in feel - at least that's the impression I got. It lacks the kind of wallop the Pogues would have delivered. Reply Notify me 1 Helpful. Als-Records The Best of the Pogues 27, Report. Coloured vinyl and 25 minute per side?? Reply Notify me Helpful. Add all to Wantlist Remove all from Wantlist. Have: Want: Avg Rating: 4. Canine Covers Animals by gatogato. CD Collection by vindent. Fairytale Of New York. -

TECNZ AGM & National Conference 2021 2 & 6 August, 2021 Famil

TECNZ AGM & National Conference 2021 2 & 6 August, 2021 Famil options Famil 1 New Plymouth Historical Walk Operator: New Plymouth i-SITE Time: Monday 2 August: 1.30-3.30pm. Must be at Puke Ariki by 1.15pm Friday 6 August: 10.30-12.30pm. Must be at Puke Ariki by 10.15am Duration: Two hours Location: Puke Ariki foyer (outside the i-SITE) Maximum: 10 pax Step back in time and experience the history of colonial New Plymouth. An easy pace walking tour developed by volunteers of Puke Ariki, the New Plymouth Historical Walk will bring the history of New Plymouth to life as you enjoy an easy stroll around the CBD taking in landmarks, places and moments from the past. Early European settlers stepped off the boat with just the bare essentials and dreams of a new life. Hear stories of hope and anguish, struggle and triumph. Discover how a bush-clad shoreline was transformed into a bustling community and meet the enterprising characters who faced down every challenge to achieve success. You will leave the walk with a New Plymouth Historical Walk booklet as a gift. Famil 2 New Plymouth Highlights Tour Operator: Nau Mai New Plymouth Tours Time: Monday 2 August: 1.30-5.30pm Friday 6 August: 9am – 1pm Duration: Four hours Pick up: The Devon Hotel Maximum: 16 pax Inclusions: Tea, coffee and cake Only have a short stay in Taranaki but want to see all the great things you’ve seen advertised? Then this is the trip for you! Your guide will pick you up from The Devon Hotel and will make sure you see all the best spots to snap those iconic pictures in the most efficient manner. -

IVAN BRUCE Archaeological Resource Management ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS at the WHITE HART HOTEL – NEW PLYMOUTH

IVAN BRUCE Archaeological Resource Management ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS AT THE WHITE HART HOTEL – NEW PLYMOUTH Archaeological Investigation Report NZHPT Authority 2011/372 Prepared for Renaissance Holdings Ltd New Plymouth March 2014 33 Scott St, Moturoa, New Plymouth [email protected] Ph 0274888215 067511645 1 | P a g e Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Physical Setting and Environment 4 2.1 Location 4 2.2 Geology and Pedology 4 2.3 Surface visibility/ Survey suitability 4 3. Statutory protection 6 4. Historic Background 6 4.1 Historic Title 6 4.2 The 1844 Rundle Structure 6 4.3 The 1887 Sanderson rebuild 9 4.4 The 1901 Messenger extension and alteration 11 4.5 Post 1900 alteration 14 5. Methodology 15 5.1 Stage 1: The renovation of the ground floor bar, kitchen, staircase and dining 15 room area from the 1887 Sanderson structure 5.2 Stage 2: The renewal of the Messenger extension 16 5.3 Stage 3: The refurbishment of the upper floor of the White Hart Hotel 17 6. Built archaeology – notable features 17 7. Site Stratigraphy 19 8. Archaeological features 21 8.1 Feature 1: White Hart Hotel Well 22 8.2 Feature 2: Cobbled courtyard 23 8.3 Feature 3 – Historic refuse 25 8.4 Feature 4 – Fireplace piles 29 9. Artifact Analysis 30 9.1 Ceramics 30 9.2 Bottle glass 32 9.3 Historic objects found within the building 32 10. Discussion 34 11. Conclusion 35 12. References 36 12.1 Written Sources 36 12.2 Images 36 12.3 Newspapers 36 12.4 Websites 36 13. -

ALBUM NOTES the Tour Continues As the Journey Unfolds

ALBUM NOTES The tour continues as the journey unfolds. I consider myself very fortunate to have new generations coming to hear the songs. Many of these listeners were not even born when I first began recording some of these tracks. Many enquire about a collection of the most popular songs. This collection has been gathered from gigs recorded over the past 3 years. It features new versions of the most requested songs. They were recorded at 17 different venues in Ireland, England and Scotland. Its been a fulfilling project, comparing different versions, hearing old songs with new arrangements and different musicians.. Its a great buzz for me…. to have such great listeners, to be still out here “On The Road“. FIRST HALF: 1 2 Ordinary Man Ride On Written by Peter Hames in the early 1980s, this song came to This was the title song of my most popular studio album me on a cassette tape as I left the Winter Gardens, Cleethorpes which was recorded in Killarney in 1985. Jimmy MacCarthy in 1985. I began listening immediately on the journey back to shared “Ride On” with me in Lombard St. Studio late one London. By the time we arrived I had the first verse chorded. It night in 1984. I first heard him sing in The Meeting Place when became the title track of my subsequent 1987 Album “Ordinary Southpaw came to play there in the late 1970s. Many of his Man”. It has been in the set these past three decades and is songs have since entered the national repertoire.