Einstein's Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus Asia Subscribe for Free Direct to Your Inbox Every Week Anzbloodstocknews.Com/Asia

FOCUS ASIA SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX EVERY WEEK ANZBLOODSTOCKNEWS.COM/ASIA Wednesday, June 9, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here STEVE MORAN - PAGE 13 FOCUS ASIA - PAGE 11 Valuable mare Tofane Read Tomorrow's Issue For It's In The Blood could still be on the market What's on Winter carnival to determine whether daughter of Ocean Park Metropolitan meetings: Canterbury races on next season (NSW), Belmont (WA) Race Meetings: Sale (VIC), Sunshine Coast (QLD), Strathalbyn (SA), Matamata (NZ) Barrier trials / Jump-outs: Kembla Grange (NSW), Pakenham (VIC), Mornington (VIC), Wangaratta (VIC) International meetings: Happy Valley (HK), Hamilton (UK), Haydock (UK), Kempton (UK), Yarmouth (UK), Cork (IRE), Lyon (FR) Sales: Inglis Digital June (Early) Sale International Sales: OBS June 2YOs and Horses of Racing Age (USA) Toofane RACING PHOTOS Coast auction last month, ran on well to finish BY TIM ROWE | @ANZ_NEWS runner-up to Emerald Kingdom (Bryannbo’s MORNING BRIEFING tradbroke Handicap (Gr 1, 1400m) Gift) in the BRC Sprint (Gr 3, 1350m) on May contender Tofane (Ocean Park), 22, a performance that convinced her owners Oaks winner Personal to whose racetrack career was extended to race her on during the Queensland winter race in the US after connections gave up a gilt- carnival. VRC Oaks (Gr 1, 2500m) winner Personal (Fastnet Sedged opportunity to sell the valuable mare at “There’s no doubt that she was highly sought Rock) is moving to the US to be trained in New the Magic Millions National Broodmare Sale, after. We had a lot of enquiry for her leading into York by Chad Brown. -

Guidetour Berne FFI Clubs Switzerland Views of Old-Town By

Guidetour Berne FFI Clubs Switzerland Berne the capital of Sitzerland, is a small to medium sized city with a population of about 136,000 in the city proper and roughly 350,000 in the agglomeration area. It sits on a peninsula formed by the meandering turns of the river Aare. The remarkable design coherence of the Berne's old town has earned it a place on the UNESCO World Heritage List. It features 4 miles of arcaded walkways along streets decked out with fountains and clock-towers. Berne is home to the prestigious University of Berne which currently enrolls approximately 13,000 students. In addition, the city has the University of Applied Science also known as Berner Fachhochschule. There are also many vocational schools and an office of the Goethe Institut. Wikipedia Cc by and https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=14/46.9419/7.4585 Views of old-town by train from Solothurn – Start in trainstation Christoffelturm The Christoffelturm was a tower built between the years 1344 and 1346. It was located in the old part of the Swiss city of Bern, in the upper section of Spitalgasse, near Holy Spirit Church. After a political decision on December 15, 1864, the Christoffelturm was removed by Gottlieb Ott, a Swiss building contractor. Ott began the destruction of the tower in spring of the following year. Bundeshaus (Federal Palace of Switzerland),The Swiss House of Parliaments is a representative building dominating the Square. Constructed by the end of 19th century. The Federal Palace refers to the building in Bern housing the Swiss Federal Assembly (legislature) and the Federal Council (executive). -

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

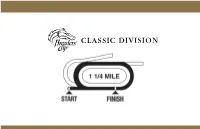

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Jul/Aug 2013

I NTERNATIONAL J OURNAL OF H IGH -E NERGY P HYSICS CERNCOURIER WELCOME V OLUME 5 3 N UMBER 6 J ULY /A UGUST 2 0 1 3 CERN Courier – digital edition Welcome to the digital edition of the July/August 2013 issue of CERN Courier. This “double issue” provides plenty to read during what is for many people the holiday season. The feature articles illustrate well the breadth of modern IceCube brings particle physics – from the Standard Model, which is still being tested in the analysis of data from Fermilab’s Tevatron, to the tantalizing hints of news from the deep extraterrestrial neutrinos from the IceCube Observatory at the South Pole. A connection of a different kind between space and particle physics emerges in the interview with the astronaut who started his postgraduate life at CERN, while connections between particle physics and everyday life come into focus in the application of particle detectors to the diagnosis of breast cancer. And if this is not enough, take a look at Summer Bookshelf, with its selection of suggestions for more relaxed reading. To sign up to the new issue alert, please visit: http://cerncourier.com/cws/sign-up. To subscribe to the magazine, the e-mail new-issue alert, please visit: http://cerncourier.com/cws/how-to-subscribe. ISOLDE OUTREACH TEVATRON From new magic LHC tourist trail to the rarest of gets off to a LEGACY EDITOR: CHRISTINE SUTTON, CERN elements great start Results continue DIGITAL EDITION CREATED BY JESSE KARJALAINEN/IOP PUBLISHING, UK p6 p43 to excite p17 CERNCOURIER www. -

204 Longways Stables 204

204 Longways Stables 204 Empire Maker Pioneerof The Nile AMERICAN Star of Goshen PHAROAH Yankee Gentleman Littleprincessemma N. (USA) Exclusive Rosette Storm Cat chesnut filly 23/03/2018 Giant's Causeway ADESTE FIDELES Mariah's Storm 2011 (USA) Imagine Sadler's Wells 1998 Doff The Derby E.B.F./B.C. Nominated AMERICAN PHAROAH (2012), 9 wins at 2 and 3 years, Breeders' Cup Classic (Gr.1). Stud in 2016. Sire of FOUR WHEEL DRIVE, Breeders' Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint, Gr.2, SWEET MELANIA, Jessamine S., Gr.2, MAVEN, Prix du Bois, Gr.3, CAFE PHAROAH, Hyacinth S., L., HARVEY'S LIL GOIL, Busanda S., ANOTHER MIRACLE, Skidmore S., American Theorem, Monarch of Egypt. 1st dam ADESTE FIDELES, 1 win, pl. 3 times at 3 years in IRE. Own sister to VISCOUNT NELSON and POINT PIPER. Dam of : N., (see above), her 2nd foal. 2nd dam IMAGINE, 4 wins at 2 and 3 years in GB and IRE, Irish 1000 Guineas (Gr.1), Oaks S.(Gr.1), C. L. Weld Park S.(Gr.3), 2nd Rockfel S.(Gr.2), £382,032. Own sister to STRAWBERRY ROAN. Dam of 12 foals of racing age, 9 winners incl. : HORATIO NELSON (c., Danehill), 4 wins at 2 years in FR, IRE & GB, Prix Jean-Luc Lagardère (Gr.1), Futurity S.(Gr.2), Superlative S.(Gr.3), 2nd Dewhurst S.(Gr.1), £284,236. VISCOUNT NELSON (c., Giant's Causeway), 4 wins at 2 to 5 in IRE & UAE, Al Fahidi Fort S.(Gr.2), 2nd Champagne S.(Gr.2), 3rd Irish 2000 Guineas (Gr.1), Eclipse S.(Gr.1), £465,391. -

Minding the Gap : a Rhetorical History of the Achievement

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap Laura Elizabeth Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Laura Elizabeth, "Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3633. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MINDING THE GAP: A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Laura Jones B.S., University of Colorado, 1995 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2010 August 2013 To the students of Glen Oaks, Broadmoor, SciAcademy, McDonough 35, and Bard Early College High Schools in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana ii Acknowledgements I am happily indebted to more people than I can name, particularly members of the Baton Rouge and New Orleans communities, where countless students, parents, faculty members and school leaders have taught and inspired me since I arrived here in 2000. I am happy to call this complicated and deeply beautiful community my home. -

Bernmobil.Ch Bernmobil.Ch Projektpartner

23 Das Fahrzeug Für Ihre Sicherheit · Hersteller: EasyMile, Toulouse (Frankreich) · Ausfallsicher durch: · doppelt ausgelegte Sensoren Selbstfahrender Kleinbus · Fahrzeug: automatisierter Kleinbus, Typ: EZ10 Gen2 · zwei unabhängige Hinderniserkennungssysteme Automatisiert unterwegs auf der Linie 23 · Antrieb elektrisch: 30-kWh-Batterie, 2 Motoren mit 8 kW · mehrfach vorhandene, unabhängige Bremssysteme · Sensortechnik: Laserscanner, Kameras · Unabhängiges Kollisions vermeidungssystem · Orientierung: Differential GPS, Laserscanner · Permanente Überwachung und Eingriffsmöglichkeit · In der Schweiz für 8 Personen zugelassen, plus Begleitperson von geschultem Begleitpersonal · Rollstuhlgeeignet · Geschwindigkeit auf maximal 20 km/h beschränkt BärenparkBärenpark MarziliMarzili BERNMOBIL Eigerplatz 3, Postfach, 3000 Bern 14 Kundendienst-Hotline 031 321 88 44 [email protected] bernmobil.ch Projektpartner: Juni 2019. Änderungen vorbehalten. bernmobil.ch e Iessech’gre ife dr Inie’le 23 Der Testbetrieb (Die Auflösung des Matteänglisch finden Sie auf unserer Facebook-Seite) · Linienführung: Marzilibahn-Talstation – Badgasse (Mattelift) – Mühlenplatz – Bärenpark (Klösterlistutz). Baustellen können Werte Fahrgäste zu temporären Einschränkungen führen. e Ab Sommer 2019 sind wir auf der Linie 23 mit einem auto- · Der selbstfahrende Kleinbus verbindet die Linie 12 mit Altenbergstrasse matisierten Kleinbus unterwegs. Wir wollen mit diesem Pilot- dem Mattelift und der Marzilibahn. ornhausbrück K betrieb in erster Linie Erfahrungen sammeln und feststellen, -

UNESCO World Heritage Properties in Switzerland February 2021

UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland February 2021 www.whes.ch Welcome Dear journalists, Thank you for taking an interest in Switzerland’s World Heritage proper- ties. Indeed, these natural and cultural assets have plenty to offer: en- chanting cityscapes, unique landscapes, historic legacies and hidden treasures. Much of this heritage was left to us by our ancestors, but nature has also played its part in making the World Heritage properties an endless source of amazement. There are three natural and nine cultur- al assets in total – and as unique as each site is, they all have one thing in common: the universal value that we share with the global community. “World Heritage Experience Switzerland” (WHES) is the umbrella organisation for the tourist network of UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland. We see ourselves as a driving force for a more profound and responsible form of tourism based on respect and appreciation. In this respect we aim to create added value: for visitors in the form of sustainable experiences and for the World Heritage properties in terms of their preservation and appreciation by future generations. The enclosed documentation will offer you the broadest possible insight into the diversity and unique- ness of UNESCO World Heritage. If you have any questions or suggestions, you can contact us at any time. Best regards Kaspar Schürch Managing Director WHES [email protected] Tel. +41 (0)31 544 31 17 More information: www.whes.ch Page 2 Table of contents World Heritage in Switzerland 4 Overview -

City Tours Januar Bis März 2021 3 Bern Welcome

CITY TOURS JANUAR BIS MÄRZ 2021 3 BERN WELCOME DIREKT BUCHUNG CHF 25.–* 90 min. 11:00 Uhr samstags Nur mit Reservation Tourist Information im Bahnhof UNESCO-Altstadtbummel Der UNESCO-Altstadtbummel beleuchtet Bern von seiner historischen Seite und führt zu den bekannt- esten Sehenswürdigkeiten: von den Stadttoren, dem Bundeshaus und dem Zytglogge (Zeitglockenturm) vorbei an den Figurenbrunnen bis zum Berner Münster. Der UNESCO-Altstadtbummel ist auch als Kombiangebot mit der Zytglogge (Zeitglockenturm)-Führung buchbar. *Reduzierte Preise für Kinder, Studierende, AHV- und IV-Bezüger sowie Inhaber des Swiss Travel Pass. Bei entsprechender Nachfrage werden die Touren zweisprachig durchgeführt. DIREKT AUF EINEM STADTRUNDGANG BUCHUNG CHF 20.–* BERN ENTDECKEN 60 min. Von den Wahrzeichen der Stadt zu geheimen Winkeln und verborgenen Schätzen: Die Stadtführungen von Bern Welcome und StattLand sind so 14:15 Uhr vielfältig wie Bern selbst. Vollgepackt mit Wissenswertem, Witzigem und Erstaunlichem, Historischem und Aktuellem sind sie lehrreich, spannend, samstags teils gruselig – und garantiert unterhaltsam. Während die Führungen von Bern Welcome Gäste und Einheimische mit Wissen und Hintergründen über Nur mit Reservation die Stadt begeistern, überraschen die Touren von StattLand mit schauspie- lerischen Darbietungen. Zytglogge (Zeitglockenturm), Seite Kramgasse Zytglogge (Zeitglockenturm)-Führung Einen Blick hinter die Zeiger des jahrhundertealten Uhrwerks werfen, die Hintergründe des Berner Wahr- zeichens erfahren und vom Turm die Aussicht geniessen – diese Führung begeistert Fans von technischen Meisterleistungen ebenso wie Geschichtsinteressierte und Panorama-Liebhaber. Die Zytglogge (Zeitglockenturm)-Führung ist auch als Kombiangebot mit dem UNESCO-Altstadtbummel buchbar. *Reduzierte Preise für Kinder, Studierende, AHV- und IV-Bezüger sowie Inhaber des Swiss Travel Pass. Bei entsprechender Nachfrage werden die Touren zweisprachig durchgeführt. -

Fabric Mulch for Tree and Shrub Plantings, Kansas State University, August 2004

KANSAS Fabric Mulch for Tree FOREST SER VICE and Shrub Plantings KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY What is Fabric Mulch? though most last well beyond the caution in riparian areas that flood Fabric mulch (often referred to time necessary to establish tree and periodically. Flooding can lower as Weed Barrier, one of many brand shrub plantings. Excessive durabil- the effectiveness of the mulch by names) is used to reduce vegetative ity results from inordinate specifi- dislocation and soil deposition. competition in newly planted trees cations and from shade created by Fabric mulch inhibits root sprouting and shrubs. This is accomplished by trees and shrubs that prevents dete- of shrubs. Root sprouting increases applying fabric over the top of trees rioration. New products are being stem density, providing valuable and shrubs after planting, cutting a tested to address this issue. wildlife habitat. hole in the fabric, and pulling the trees and shrubs through the hole. It When Should Fabric Fabric Mulch is made of a black, woven, perme- Mulch be Used? Specifications able, polypropylene geotextile that Fabric mulch is appropriate to Fabric mulch is available in can withstand the trampling of deer help establish windbreaks, shel- a variety of sizes and specifica- and deterioration from sunlight. terbelts, living snowfences, and tions. It can be purchased in rolls Fabric mulches conserve soil mois- other small tree and shrub plant- that can be applied by machine, or ture by reducing evaporation. Fabric ings. Fabric should be used with in squares that can be applied by mulches eventually biodegrade, hand. Rolls may contain from 300 to 750 feet of fabric and range from 4 to 10 feet wide. -

INVENTING REALITY EALITY “This Book Makes for Smooth Riding Over the Rough Terrain of

“...a rich account of the dogged and often futile attempt of physicists to talk about nature.” —Alan Lightman Author of Time Travel and Papa Joe’s Pipe: Essays on the Human side of Science INVENTING INVENTING REALITY EALITY “This book makes for smooth riding over the rough terrain of ... PHYSICS AS modern physics... [Gregory] steers the reader unerringly to his provocative conclusion: reality is a function of language...” R —Lynn Margulis LANGUAGE Coauthor of Microcosmos, Five Kingdoms, and Origins of Sex Physicists do not discover the physical world. Rather, they invent a physical world—a story that closely fits the facts they create in ex- perimental apparatus. From the time of Aristotle to the present, In- venting Reality explores science’s attempts to understand the world by inventing new vocabularies and new ways to describe nature. Drawing on the work of such modern physicists as Bohr, Einstein, and Feynman, Inventing Reality explores the relationship between language and the world. Using ingenious metaphors, concrete examples from everyday life, and engaging, nontechnical language, Gregory color- fully illustrates how the language of physics works, and demonstrates the notion that, in the words of Einstein, “physical concepts are free creations of the human mind.” BRUCE GREGORY is an Associate Director of the Harvard- Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. For over twenty years he has made science intelligible to audiences ranging from junior high school students to Members of Congress. B R U C E G R E G O R Y Back cover Front cover INVENTING INVENTING REALITY REALITY PHYSICS AS LANGUAGE ❅ Bruce Gregory For Werner PREFACE Physics has been so immensely successful that it is difficult to avoid the conviction that what physicists have done over the past 300 years is to slowly draw back the veil that stands between us and the world as it really is—that physics, and every science, is the discovery of a ready-made world. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start)