Road to Trinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WINTER 2013 - Volume 60, Number 4 the Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A

WINTER 2013 - Volume 60, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

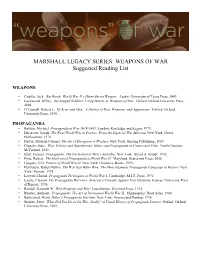

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: WEAPONS of WAR Suggested Reading List

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: WEAPONS OF WAR Suggested Reading List WEAPONS • Couffer, Jack. Bat Bomb: World War II’s Other Secret Weapon. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992. • Lockwood, Jeffrey. Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. • O’Connell, Robert L. Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons, and Aggression. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. PROPAGANDA • Balfour, Michael. Propaganda in War 1939-1945. London: Routledge and Kegan, 1979. • Darracott, Joseph. The First World War in Posters: From the Imperial War Museum. New York: Dover Publications, 1974 • Dewar, Michael Colonel. The Art of Deception in Warfare. New York: Sterling Publishing, 1989. • Dipaolo, Marc. War, Politics and Superheroes: Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film. North Carolina: McFarland, 2011. • Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965. • Fyne, Robert. The Hollywood Propaganda of World War II. Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2008. • Gregory, G.H. Posters of World War II. New York: Gramercy Books, 1993. • Hertzstein, Robert Edwin. The War that Hitler Won: The Most Infamous Propaganda Campaign in History. New York: Putnam, 1978. • Laswell, Harold. Propaganda Techniques in World War I. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1971. • Laurie, Clayton. The Propaganda Warriors: America’s Crusade Against Nazi Germany. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1996. • Rendell, Kenneth W. With Weapons and Wits. Lincolnshire: Overlord Press, 1992. • Rhodes, Anthony. Propaganda: The Art of Persuasion World War II. Minneapolis: Book Sales, 1988. • Rutherford, Ward. Hitler’s Propaganda Machine. New York: Grosset and Dunlop, 1978. • Stanley, Peter. What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? A Visual History of Propaganda Posters. -

The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay: the Crew

AFA’s Enola Gay Controversy Archive Collection www.airforcemag.com The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay From the Air Force Association’s Enola Gay Controversy archive collection Online at www.airforcemag.com The Crew The Commander Paul Warfield Tibbets was born in Quincy, Ill., Feb. 23, 1915. He joined the Army in 1937, became an aviation cadet, and earned his wings and commission in 1938. In the early years of World War II, Tibbets was an outstanding B-17 pilot and squadron commander in Europe. He was chosen to be a test pilot for the B-29, then in development. In September 1944, Lt. Col. Tibbets was picked to organize and train a unit to deliver the atomic bomb. He was promoted to colonel in January 1945. In May 1945, Tibbets took his unit, the 509th Composite Group, to Tinian, from where it flew the atomic bomb missions against Japan in August. After the war, Tibbets stayed in the Air Force. One of his assignments was heading the bomber requirements branch at the Pentagon during the development of the B-47 jet bomber. He retired as a brigadier general in 1966. In civilian life, he rose to chairman of the board of Executive Jet Aviation in Columbus, Ohio, retiring from that post in 1986. At the dedication of the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar- Hazy Center in December 2003, the 88-year-old Tibbets stood in front of the restored Enola Gay, shaking hands and receiving the high regard of visitors. (Col. Paul Tibbets in front of the Enola Gay—US Air Force photo) The Enola Gay Crew Airplane Crew Col. -

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

Trinity Scientific Firsts

TRINITY SCIENTIFIC FIRSTS THE TRINITY TEST was perhaps the greatest scientifi c experiment ever. Seventy-fi ve years ago, Los Alamos scientists and engineers from the U.S., Britain, and Canada changed the world. July 16, 1945 marks the entry into the Atomic Age. PLUTONIUM: THE BETHE-FEYNMAN FORMULA: Scientists confi rmed the newly discovered 239Pu has attractive nuclear Nobel Laureates Hans Bethe and Richard Feynman developed the physics fi ssion properties for an atomic weapon. They were able to discern which equation used to estimate the yield of a fi ssion weapon, building on earlier production path would be most effective based on nuclear chemistry, and work by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls. The equation elegantly encapsulates separated plutonium from Hanford reactor fuel. essential physics involved in the nuclear explosion process. PRECISION HIGH-EXPLOSIVE IMPLOSION FOUNDATIONAL RADIOCHEMICAL TO CREATE A SUPER-CRITICAL ASSEMBLY: YIELD ANALYSIS: Project Y scientists developed simultaneously-exploding bridgewire detonators Wartime radiochemistry techniques developed and used at Trinity with a pioneering high-explosive lens system to create a symmetrically provide the foundation for subsequent analyses of nuclear detonations, convergent detonation wave to compress the core. both foreign and domestic. ADVANCED IMAGING TECHNIQUES: NEW FRONTIERS IN COMPUTING: Complementary diagnostics were developed to optimize the implosion Human computers and IBM punched-card machines together calculated design, including fl ash x-radiography, the RaLa method, -

Trivia Questions

TRIVIA QUESTIONS Submitted by: ANS Savannah River - A. Bryson, D. Hanson, B. Lenz, M. Mewborn 1. What was the code name used for the first U.S. test of a dry fuel hydrogen bomb? Castle Bravo 2. What was the name of world’s first artificial nuclear reactor to achieve criticality? Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), I also seem to recall seeing/hearing them referred to as “number one,” “number two,” etc. 3. How much time elapsed between the first known sustained nuclear chain reaction at the University of Chicago and the _____ Option 1: {first use of this new technology as a weapon} or Option 2: {dropping of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima} A3) First chain reaction = December 2nd 1942, First bomb-drop = August 6th 1945 4. Some sort of question drawing info from the below tables. For example, “what were the names of the other aircraft that accompanied the Enola Gay (one point for each correct aircraft name)?” Another example, “What was the common word in the call sign of the pilots who flew the Japanese bombing missions?” A4) Screenshots of tables from the Wikipedia page “Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki” Savannah River Trivia / Page 1 of 18 5. True or False: Richard Feynman’s name is on the patent for a nuclear powered airplane? (True) 6. What is the Insectary of Bobo-Dioulasso doing to reduce the spread of sleeping sickness and wasting diseases that affect cattle using a nuclear technique? (Sterilizing tsetse flies; IAEA.org) 7. What was the name of the organization that studied that radiological effects on people after the atomic bombings? Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission 8. -

Companionpaw Prints Summer 2014

COMPANIONpaw prints Summer 2014 Summer Tips for You and Your Pet! There is no better feeling than hanging outside with your animals on a beautiful summer day. It is important to know the risks and limitations of your pet’s outdoor exposure during the hot months of summer. We have some tips for you to follow to assure your pet’s safety! Follow these tips below, courtesy of the ASPCA: Visit the Vet - A visit to the veterinarian for a spring or early summer check-up is a must. Make sure your pets get tested for heartworm if they aren’t on year-round preventive medication. Do parasites bug your animal CAMDEN COUNTY companions? Ask your doctor to recommend a safe flea and tick control ANIMAL SHELTER program. 125 County House Rd. Know the Warning Signs - Symptoms of overheating in pets include Blackwood, NJ 08012 excessive panting or difficulty breathing, increased heart and respiratory Phone: 856.401.1300 rate, drooling, mild weakness, stupor or even collapse. They can also Fax: 856.401.1309 include seizures, bloody diarrhea and vomit along with an elevated body Email: [email protected] temperature of over 104 degrees. Animals with flat faces, like Pugs and www.ccasnj.org Persian cats, are more susceptible to heat stroke since they cannot pant Mailing Address: as effectively. These pets, along with the elderly, the overweight, and PO Box 475 those with heart or lung diseases, should be kept cool in air-conditioned Blackwood, NJ 08012 rooms as much as possible. No Parking! - Never leave your animals alone in a parked vehicle. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Calontir Post-Revel Songbook Primer

fl Calontir Post-ReiJef "- CREDITS ' .. Songs edited by Chrystofer Kensor Typed by Chrystofer Kensor Proofread by Katr~<ina op den Dijk Andreas of Green Village Rhianna of Ceffyl TWr Collated by Chrystofer Kensor Edward of Wyvern' s Keep Printed by Edward of Wyvern's Keep Additional Printers Kinko's Copies Easy Print Printing Cover Art by William Blackfox This is the Calontir Post-Revel Songbook Primer. It is not an offical publication of the Society for Creative Anachronism, and does not delineate SCA policies. It is available from the editior for $1.00 I volume {$5.00 for the complete set) at 2818 Michigan, Topeka, KS 66605. This is a non-prophit publication for the benifit of the populace. A.CA.LONTJR -pEoplEs SON). )J~JO)OJRE . volumE 1 CALONTIR'S TOP FIFTY Another Tournament Fight D-1 Conn McNiel Ball of Ball)'Noor C-1 various Bare is the Brotherless Back E-1 Aeruin ni hEarain 6 Chonemara Bastard King of England C-2 traditional y Brom' s Reign D-2 Brom Blackhand Calontir Game E-2 Ekaterina Zvyosdosomtzeva Kievskaya ' Calontir Stands Alone A-1 Brom Blackhand Catalan Vengeance E-3 Moses Ben Eldad :. Coeur d' fnnui Song D-3 William Coeur du Boeuf 1 Duchess and the Lecher C-4 Dun CCM D-4 traditional Finnegan' s Wake B-2 traditl.onal FollCM Me Up To Car lCM B-3 Patrick Joseph Me Call Gang Bang Song C-5 various Gcx::ld Ship Venus C-6 traditional Great God Tyr D-5 Ruyard Kipling Greyhound Bound for Pennsic E-4 Koshka Hampster Song A-2 Chrystofer Kensor Hot Spur A-3 Andrew Lyon of Wol venwood Johnny I Hardly Knew You B-4 traditional Jolly -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

Museum Newsletter Issue 3 2019

MUSEUM OF HERITAGE & ARTS September 2019 Gerald Armijo Art Exhibit Location September 14 - November 2, 2019 Los Lunas Museum of Heritage & Arts 251 Main St. SE Los Lunas, NM 505-352-7720 Museum Hours Tuesday 10:00am to 5:00pm Wednesday 10:00am to 5:00pm Thursday 10:00am to 5:00pm Friday 10:00am to 5:00pm Gerald Armijo, Artist Saturday 10:00am to 5:00pm Sunset in Arizona (acrylic) Check us Out!!! Local artist Gerald Armijo won the Los Lunas Museum of Heritage & Art's Visit the Exhibits Attend a Public Program 2018 Juried Art Show entitling him to a solo exhibition. The art on exhib- Research Local & State it is in a variety of media that express the area’s rich history as well as History portraits and other subject matter that displays Gerald's artistic talent. Find Your Family History His work will be on display September 14 - November 2, 2019. Contribute Your History 7th Annual Juried Art Show Applications For information on Deadline October 12, 2019 programs & collections please contact: The Los Lunas Museum of Jan Micaletti, BA Heritage & Arts is accept- Museum Specialist ing submissions for the [email protected] Seventh Annual Juried Art Rebecca Ortiz, ABS Exhibit "Frontiers of New Museum Technician Mexico." Selected entries [email protected] will be displayed from November 9, 2019 to Christina Marshall, BFA Museum Technician January 10, 2020. The [email protected] entry deadline is October 12, 2019. Encino Ranch House Enhanced photo by Cynthia J. Shetter Page 2 September 2019 Museum of Heritage & Arts The Preservation of the Abo Ruins & History of Federico Sisneros September 21, 2019 2:00 PM - 4:00 PM The San Gregorio de Abo Mission of Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument sits west of the town of Mountainair, New Mexico, and contains approximately 370 acres. -

―Basically a True Story:‖ the Beginning Or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb

―Basically a True Story:‖ The Beginning or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb By Theresa Lynn Verstreater B.A. in History, December 2008, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts January 31, 2015 Thesis directed by Charles Thomas Long Assistant Professor of History Abstract of Thesis ―Basically a True Story:‖ The Beginning or the End, Fat Man and Little Boy, and American Remembrance of the Atomic Bomb The impact of film as a vehicle for dissolution of information should not be discounted because it allows the viewer to experience the story alongside the characters and makes historical moments more relatable when presented through the modern medium. This, however, can be a double-edged sword as it relates to the creation of collective memory. This thesis examines two films from different eras of the post-atomic world, The Beginning or the End (1947) and Fat Man and Little Boy (1989), to discover their strengths and weaknesses both cinematically and as historical films. Studied in this way, the films reveal a leniency toward what professional historians might consider to be historical ―truth‖ while emphasizing moral ambiguity about the bomb and the complex relationships among the men and women responsible for its creation. While neither film boasts outstanding filmmaking, each attempts to educate the viewer while maintaining entertainment value through romantic subplots and impressive special effects.