Maneuvers Around Vicksburg and West Virginia Emancipation Http

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning Point: 1863

THE INQUIRY CIVIL WAR CURRICULUM BY THE AMERICAN BATTLEFIELD TRUST GOAL 5 | LESSON PLAN | MIDDLE SCHOOL Turning Point: 1863 Grades: Middle School Approximate Length of Time: 3 hours (Time includes writing the final essay.) Goal: Students will be able to argue how certain events in 1863 changed the trajectory of the war. Objectives: 1. Students will be able to complete a graphic organizer, finding key information within primary and secondary sources. 2. Students will be able to address a question about a historic event, providing evidence to support their answer from primary and secondary sources. Common Core: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7 Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.7 Conduct short research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated The Inquiry Civil War Curriculum | Middle School Battlefields.org The Inquiry Civil War Curriculum, Goal 5 Turning Point: 1863 question), drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions that allow for multiple avenues of exploration. -

Abraham Lincoln the Face of a War

SPRING 2009 AbrAhAm LincoLn THE FACE of A WAR Smithsonian Institution WWW.SMITHSONIANEDUCATION.ORG NATIONAL STANDARDS IllUSTRATIONS CREDITS The lessons in this issue address NCSS National Cover: Library of Congress. Inside cover: Green Stephen Binns, writer; Michelle Knovic Smith, History Standards for the Civil War and NAEA Bay and De Pere Antiquarian Society and the publications director; Darren Milligan, art standards for reflecting upon and assessing Neville Public Museum of Brown County. Page 1: director; Candra Flanagan, education consultant; works of visual art. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Design Army, designer Page 2: National Museum of American History. STATE STANDARDS Page 3: Library of Congress. Pages 6–7 (clockwise ACKNOWleDGMENTS See how the lesson correlates to standards in from top): Lithograph and photograph details, Thanks to Rebecca Kasemeyer, David Ward, and your state by visiting smithsonianeducation. National Portrait Gallery; print, National Museum Briana Zavadil White of the National Portrait org/educators. of American History; broadside and detail of Gallery, and Harry Rubenstein of the National Second Inauguration photograph, Library of Museum of American History. Smithsonian in Your Classroom is produced by the Congress. Page 11: Library of Congress. Page Smithsonian Center for Education and Museum 13: National Portrait Gallery, Alan and Lois Fern Studies. Teachers may duplicate the materials Acquisition Fund. Back cover: Detail of portrait cE oF A WAr for educational purposes. by William Willard, National Portrait Gallery, gift of Mr. and Mrs. David A. Morse. C ONTENTS BACKGROUND 1 LessON 1 3 TeACHING MATERIAls 4–9 BACKGROUND 10 LessON 2 12 ON THE LIFE-MASK OF AbRAHAM LINCOLN This bronze doth keep the very form and mold Of our great martyr’s face. -

David D. Porter Family Papers a Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress

David D. Porter Family Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1997 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm79036574 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms000015 Prepared by Allen E. Kitchens Revised by Margaret McAleer Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2000 Revised 2010 April Collection Summary Title: David D. Porter Family Papers Span Dates: 1799-1899 ID No.: MSS36574 Creator: Porter, David D. (David Dixon), 1813-1891 Extent: 7,000 items Extent: 33 containers plus 1 oversize Extent: 10 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/mm79036574 Summary: Naval officer. Correspondence, journals, logbooks, orders, reports, memoranda, family papers, drafts of articles, memoirs, poems, short stories, and other literary writings, sketches, photographs, and printed matter documenting David D. Porter's naval career. Includes material on his years as a midshipman, his service in the Mexican War, trips to the Mediterranean to secure camels for use by the United States Army, Civil War service, superintendency of the United States Naval Academy, mission to Santo Domingo concerning the lease of Samaná Bay in the Dominican Republic, and his career as an advisor to the Navy Department (1870-1891) and chairman of the United States Navy Board of Inspection and Survey (1877-1891). Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. -

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter: David Farragut—The Civil War Years Part Two of a Three-Part Series

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter: David Farragut—The Civil War Years Part Two of a three-part series Vice Admiral Jim Sagerholm, USN (Ret.), October 19, 2020 blueandgrayeducation.org David Farragut | National Portrait Gallery When Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861, David Farragut proclaimed his continuing allegiance to the Stars and Stripes and moved his family to the North. His birth in Tennessee and the residence of his sisters and brother in New Orleans caused some to question his loyalty. But the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, liked what he saw in Farragut: “He was attached to no clique, . was as modest and truthful as he was self-reliant and brave . and resorted to none of the petty contrivances common to some . ‘ Thus, when looking for an officer to command the capture of New Orleans, Welles chose Farragut, even though Farragut had no experience commanding more than one vessel. The principal defense for New Orleans from threats via the Gulf were Forts Jackson and St. Philip, located some 40 miles south of the city. It was generally believed that wooden-hulled ships would at best be severely damaged if not sunk in trying to run past the formidable artillery of a fort. Farragut was one of the few who thought otherwise. In addition, his foster brother, Commander David Dixon Porter, proposed assembling a squadron of gunboats, each armed with a 13-inch mortar that could hurl a 200-pound shell 3 miles, claiming that they could reduce the forts sufficiently to permit Farragut’s ships to run past them with minimal damage. -

Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: the Mississippi Squadron

Civil War Book Review Spring 2008 Article 10 Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron Andrew Duppstadt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Duppstadt, Andrew (2008) "Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 10 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol10/iss2/10 Duppstadt: Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron Review Duppstadt, Andrew Spring 2008 Joiner, Gary D. Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, $24.95 softcover ISBN 9780742550988 War on the Mississippi In the growing body of literature on the naval aspects of the American Civil War a number of topics continue to get short shrift. One of these topics is the role of the U.S. Navy in the southern inland waterways, particularly those in the western theater. It seems that each week there is a new study on the CSS Alabama, CSS Shenandoah, USS Monitor, and any number of other popular subjects. The less glamorous and glorious are often forgotten. Gary D. Joiner makes a valiant effort at resolving this deficiency in this book. Joiner has spent much of his career bringing the war on the western waters to light, authoring or editing a number of works on the 1864 Red River Campaign. However, he has widened his scope for this work and has produced a fine book that anyone interested in the naval war or the war in the West should read. The first chapter is a succinct yet thorough introduction to the state of the U.S. -

U.S. Coast Survey Was Pivotal in the Bombardment and Surrender of Fort Jackson and Fort St

U.S. Coast Survey was pivotal in the bombardment and surrender of Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip Hydrographers and geodesists with the U.S. Coast Survey were involved in several of the major Union successes in the Civil War. One of the most revolutionary contributions was their role in the six-day mortar bombardment ‒ with the subsequent surrenders ‒ of Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, a decisive battle for possession of New Orleans in April 1862. U.S. Coast Survey teams mapped the terrain and charted rivers and coastlines for military action during the Civil War, but their creative and even daring use of science and engineering went beyond what we normally consider to be “surveying.” Coast Survey Assistant Ferdinand Gerdes was one of Coast Survey’s heroes of the war, and rebel troops at Fort Jackson literally felt the repercussions produced by his ingenuity and use of science-based principles. Gerdes would give coordinates to Union flotilla gunboats so ‒ for the first time, ever ‒ they could aim their weapons without seeing the target. Instead of judging target distance by sight, they would rely on mathematical calculations, using survey coordinate points established by Coast Survey teams. New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy, was defended by Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, located at a short bend in the Mississippi River, 60 miles below the city. To capture the city, and open the Mississippi River to Union forces, Commander David Dixon Porter got President Lincoln’s approval for a daring plan to disable the guns at the forts. -

The Confederate Naval Buildup

Naval War College Review Volume 54 Article 8 Number 1 Winter 2001 The onfedeC rate Naval Buildup David G. Surdam Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Surdam, David G. (2001) "The onfeC derate Naval Buildup," Naval War College Review: Vol. 54 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol54/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Surdam: The Confederate Naval Buildup THE CONFEDERATE NAVAL BUILDUP Could More Have Been Accomplished? David G. Surdam he Union navy’s control of the American waters was a decisive element in Tthe outcome of the Civil War. The Federal government’s naval superiority allowed it to project power along thousands of miles of coastline and rivers, sub- sist large armies in Virginia, and slowly strangle the southern economy by sty- mieing imports of European and northern manufactures and foodstuffs, as well as of exports of southern staples, primarily raw cotton. The infant Confederate government quickly established a naval organization. Jefferson Davis chose Stephen Mallory as Secretary of the Navy. Mr. Mallory confronted an unenviable task. The seceding states possessed no vessels capable of fighting against the best frigates in the Federal navy, nor did those states possess most of the necessary raw materials and industries needed to build modern warships. -

2014 USNA Viewbook.Docx

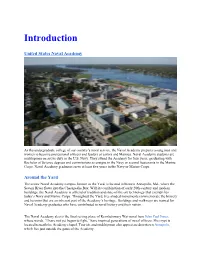

Introduction United States Naval Academy As the undergraduate college of our country’s naval service, the Naval Academy prepares young men and women to become professional officers and leaders of sailors and Marines. Naval Academy students are midshipmen on active duty in the U.S. Navy. They attend the Academy for four years, graduating with Bachelor of Science degrees and commissions as ensigns in the Navy or second lieutenants in the Marine Corps. Naval Academy graduates serve at least five years in the Navy or Marine Corps. Around the Yard The scenic Naval Academy campus, known as the Yard, is located in historic Annapolis, Md., where the Severn River flows into the Chesapeake Bay. With its combination of early 20th-century and modern buildings, the Naval Academy is a blend of tradition and state-of-the-art technology that exemplifies today’s Navy and Marine Corps. Throughout the Yard, tree-shaded monuments commemorate the bravery and heroism that are an inherent part of the Academy’s heritage. Buildings and walkways are named for Naval Academy graduates who have contributed to naval history and their nation. The Naval Academy also is the final resting place of Revolutionary War naval hero John Paul Jones, whose words, “I have not yet begun to fight,” have inspired generations of naval officers. His crypt is located beneath the Academy chapel. Tourists and midshipmen also appreciate downtown Annapolis, which lies just outside the gates of the Academy. History Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft laid the foundation for the Naval Academy when, in 1845, he established the Naval School at Fort Severn in Annapolis. -

“A Death-Shock to Chivalry, and a Mortal Wound to Caste”: the Story of Tad and Abraham Lincoln in Richmond

“A Death-shock to Chivalry, and a Mortal Wound to Caste”: The Story of Tad and Abraham Lincoln in Richmond RICHARD WIGHTMAN FOX On Tuesday, April 4, 1865, his twelfth birthday, Tad Lincoln woke up in his cabin on the USS Malvern as it lay moored on the James River at City Point, Virginia, the headquarters of General Grant. On this day of celebration, with his mother home in Washington and his twenty-one- year-old brother Captain Robert Lincoln busily engaged on Grant’s staff, Tad could look forward to getting his father more or less to himself. For a boy captivated by the war, by soldiers, by the entire adult male world of work—he had already befriended the military band members at City Point and the mechanics in the engine room of the ship—this birthday bonanza far surpassed any he could have imagined. On April 3, Union forces had finally captured Richmond, the Confederate capital, and this morning the president was taking him upriver for a victory tour of the city. Tad knew some of what to expect, since the day before, as federal troops marched into Richmond, he and Robert had witnessed the ecstatic reception their father received from African Americans and Union soldiers in newly occupied Petersburg, fifteen miles southwest of City Point (and thirty miles south of Richmond). Admiral David Dixon Porter, who had traveled there by train with the president, later recalled the streets of Petersburg being “alive with negroes, who were crazy to see their savior, as they called the President.” Regiment after regiment of soldiers offered “three cheers for Uncle Abe,” along with hearty cries on the order of “we’ll get ’em, Abe, where the ‘boy had the hen,’” and “you go home and sleep sound tonight; we boys will put you through!” In Richmond too the president would be welcomed with yells, songs, and prayers of thanksgiving. -

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut Gravesite

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FARRAGUT, ADMIRAL DAVID GLASGOW, GRAVESITE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Farragut, Admiral David Glasgow, Gravesite Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Lot Number 1429-44, Section 14, Aurora Hill Plot Not for publication: Woodlawn Cemetery City/Town: Bronx Vicinity: State: NY County: Bronx Code: 005 Zip Code: 10470 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: ___ Public-State: ___ Site: X Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing buildings 1 sites structures 1 objects 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form ((Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FARRAGUT, ADMIRAL DAVID GLASGOW, GRAVESITE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Plaaces Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that tthis ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _____ meets ____ does not meet the Natioonal Register Criteria. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

Cornerstone of Union Victory: Officerar P Tnerships in Joint Operations in the West

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2018 Cornerstone of Union Victory: Officerar P tnerships in Joint Operations in the West Aderian Partain University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Partain, Aderian, "Cornerstone of Union Victory: Officer Partnerships in Joint Operations in the West" (2018). Master's Theses. 379. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/379 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cornerstone of Union Victory: Officer Partnerships in Joint Operations in the West by Aderian Partain A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Dr. Susannah Ural, Committee Chair Dr. Kenneth Swope, Committee Member Dr. Kyle Zelner, Committee Member ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Susannah Ural Dr. Kyle Zelner Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School August 2018 COPYRIGHT BY Aderian Partain 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT The American Civil War included one of the pivotal naval contests of the nineteenth century. A topic of considerable importance is the joint operations on the western waters that brought about a string of crucial victories in the conflict for the Union.